Massimo Amadori is a member of Resistenze Internazionali (ISA in Italy).

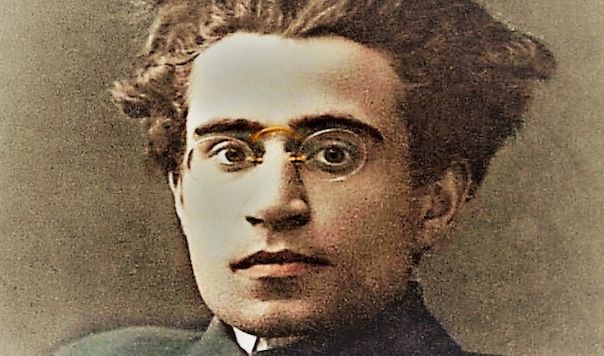

Antonio Gramsci is certainly one of the most popular Marxist thinkers, and is considered one of the greatest intellectuals of the twentieth century. In recent years, his ideas have been particularly studied and appreciated by the Latin American left, as they look to the political legacy of this Sardinian revolutionary. Even in Italy today, on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the birth of the Communist Party of Italy (PCI), the figure of Gramsci is making a comeback.

As Marxists, we too must look to this great revolutionary, whose ideas can still teach us a lot. It is certainly necessary to free the figure of Antonio Gramsci from all the falsifications of Stalinism and the bourgeoisie, which have created an image of Gramsci which is devoid of any revolutionary meaning.

The ‘Red Period’

To understand Antonio Gramsci’s political legacy, it is necessary to read his writings and study the evolution of his thought over the years. This forces us to analyse the historical context in which Gramsci worked, from the Red Biennium – Two Red Years (1919–1920) until his death in a fascist prison in 1937.

Antonio Gramsci was born in Sardinia in 1891. At a very young age he moved to Turin; it was in the Piedmontese capital that he was first attracted to socialist ideas, and where he joined the Italian Socialist Party (PSI).

After the First World War, Italy was shaken by a two-year wave of strikes, worker and peasant protests. The mass workers’ movement was not limited to economic demands, but also had revolutionary potential inspired by the Bolshevik revolution of October 1917. The workers of northern Italy did not just go on strike, but often occupied factories and elected worker’s councils, following the example of the Russian Soviets.

A situation of dual power developed, in which the workers’ councils (the socialist state in embryonic form) competed for power with the bourgeois state. In the political elections of 1919, the PSI became the main party in the country. “Do as in Russia” became the slogan of the Italian proletariat. In this context, Antonio Gramsci represented the most combative and revolutionary wing of the Italian Socialist Party and had a leading role in the formation of the factory councils, which he correctly saw as the organs of the future socialist state.

Although workers did manage to wrestle important social gains from the employers, such as the 8-hour working day, the revolutionary aspirations of the Italian proletariat were soon stifled by the reformist leaders of the PSI and the trade union bureaucracies. The Red Biennium was defeated.

Antonio Gramsci, Amedeo Bordiga and the entire revolutionary wing of the PSI lacked the decisiveness needed to break with the reformists and therefore were unable to take the initiative, to lead the workers to take over political power. Despite this, in this period Gramsci’s fame in the socialist movement grew enormously. In 1919 the Sardinian revolutionary founded L’Ordine Nuovo (The New Order), a newspaper that united the entire revolutionary wing of the PSI in Turin.

Italian fascism

The response of the big capitalists and landowners to the workers’ and peasants’ struggles, and to the advance of the socialists was to create and finance fascist squads. These fascist squads beat and even murdered striking workers, peasants who had occupied the land, trade unionists and socialists.

Fascism was the price that the Italian workers’ movement had to pay for the defeat of the ‘Red Biennium’. During the wave of fascist violence, in Livorno on January 21, 1921, the PSI underwent the most important split in its history: the revolutionary Marxist wing of the party led by Antonio Gramsci and Amedeo Bordiga broke off to form the Communist Party of Italy (PCI). The PCI became the Italian section of the Third International of Lenin and Trotsky. The separation from the reformists was certainly late, because by now the workers’ movement had been defeated by the fascist squads, and the forces of reaction were winning throughout Italy.

Bordiga’s ultra-leftism

The PCI found itself immediately isolated from the popular masses, especially due to the sectarian and ultra-left policies followed by Bordiga. The leadership of the party was initially in the hands of the Neapolitan revolutionary, who refused any form of anti-fascist united front with the PSI and other forces of the workers’ movement, clashing with Lenin, Trotsky and the leadership of the International, who argued that the PCI should offer a united front of workers’ organisations to fight fascism. Gramsci in this period, although not always in agreement with Bordiga, accepted his sectarian policy.

In 1922 Antonio Gramsci visited Moscow and whilst there, having debated with Lenin, Trotsky and other Bolshevik leaders, he became convinced that Bordiga’s ultra-left policy was wrong and that a united front policy of the left against fascism was necessary. Later he returned to Italy determined to change the party’s policy on this issue in opposition to the “Bordigist” faction.

In the meantime, Mussolini had come to power, immediately making life difficult for the young Communist Party. The fascist squads had in fact already started to arrest and assassinate numerous Communist militants. Gramsci, however, was elected to parliament and as such in the early years of fascism he had immunity. This lasted until 1926, when a further series of dictatorial laws was passed that liquidated all opposition to fascism, finally making Italy a totalitarian regime.

Gramsci leads the PCI

In the years 1923–1924, Antonio Gramsci defended the policies of the International. Although still in a minority, with the support of the International and using bureaucratic methods, the Gramsci-wing of the party organised an internal coup to oust Bordiga. Such undemocratic methods would have been unthinkable in the early years of the Communist International; but the Comintern was already becoming bureaucratized as Stalinism strengthened within the USSR itself.

Gramsci’s political battle against Bordiga was correct, and in line with the non-sectarian positions of Lenin and Trotsky. However, it was a battle waged with undemocratic methods, thus in opposition to the Bolshevik approach. At the 1926 Lyon congress, Gramsci dealt the “Bordigist” leadership the final blow, following instructions from the International. In this period the Sardinian revolutionary sided with the Stalinist faction of the Bolshevik Party, mistakenly believing that Trotsky’s positions were similar to those of Bordiga. Despite this mistake, Gramsci was never a Stalinist and, in a letter addressed to the Central Committee of the CPSU in 1926, while politically supporting the majority of the Soviet party, he harshly criticised the bureaucratic and anti-democratic methods that Stalin was using against the Trotskyists. This was in 1926, long before the Moscow trials and the great purges, with which Stalin exterminated the entire old Bolshevik guard.

Togliatti and Stalin

In any case, Gramsci’s position brought him into conflict with another Italian communist, Palmiro Togliatti, who at that time was in Moscow, and was an unreserved supporter of Stalin. He ensured Gramsci’s letter never reached the Central Committee of the CPSU. In the same year Gramsci was arrested by the fascist regime and sentenced to a long prison sentence. This left the PCI under the Stalinist leadership of Togliatti, who for many years was one of Stalin’s main collaborators and was complicit in many of his crimes.

Antonio Gramsci, although in prison and seriously ill, did not give up and wrote prolifically. His famous Notebooks from Prison, probably the most widely read work by Antonio Gramsci, date to this period of detention. These writings cover various issues, and contain several innovative conceptions of Marxist theory. His judgments on Trotsky, however, are hasty and demonstrate a lack of knowledge about Trotsky’s ideas due, undoubtedly, to the fact that Gramsci remained isolated in prison and had no access to information from the outside world. Consequently, he lacked an understanding about what was happening in the Soviet Union. Despite these limitations, Gramsci was very critical of Stalin and Togliatti, in particular with regard to the ultra-left and sectarian politics of the “Third Period”.

“Third period” ultra-leftism

In fact, from 1928 to 1934 the “Stalinised” Communist International experienced an ultra-left phase, in which the Communist Parties identified fascism with social democracy, defining it as social-fascism. From prison Gramsci opposed this crazy policy, which in 1933 in Germany prevented any united front between communists and social democrats, allowing the Nazis to take power almost unopposed. The criticisms that Gramsci addressed at that time to the Stalinist leadership of the PCI coincided with those made by the Trotskyists of the New Italian Opposition (NOI), linked to Trotsky’s International Left Opposition. The NOI was headed by the Trotskyists, Pietro Tresso, Alfonso Leonetti and Alberto Ravazzoli, all of whom had been expelled from the PCI in 1930 for their opposition to Stalinism.

The Italian Trotskyists shared with Gramsci opposition to the line of social-fascism. Gramsci, however, being in prison, was unaware of this. This is not to argue that Gramsci had become a Trotskyist, but he was certainly not a Stalinist and his break with Togliatti was sharp. While isolated in prison some of Gramsci’s own party comrades had turned away from him. The Stalinists in turn avoided Gramsci, unable to forgive him for his “heterodoxy.”

We do not know how his thoughts would have evolved because, due to his suffering in the fascist prisons, Gramsci died in 1937. The fascists had killed one of the great minds of the Italian working class.

Gramsci’s political legacy

The most important aspect of the political legacy of Antonio Gramsci is what happened after his death. Togliatti’s Stalinists, who had opposed him in life, hypocritically presented themselves as the political heirs of Gramsci and distorted his thinking, presenting him as a reformist and anti-Trotskyist. From 1935, the Stalinists abandoned their ultra-left phase and, rejecting the united front approach of the Bolsheviks, introduced the popular front strategy, inaugurating a reformist policy of class collaboration with the bourgeoisie. This policy was never overturned, in Italy it reached its peak with the Resistance during WW2, when the PCI led by Togliatti, under Stalin’s instructions, abandoned any revolutionary perspective and promoted a policy of national unity with the bourgeois forces, even with the monarchy and ex-fascists who had gone over to the side of the allies.

In the immediate post-war period, the PCI entered bourgeois governments and participated in the reconstruction of the republican bourgeois state. The repressive apparatuses of the state remained the same as those created during the fascist regime, and the fascists were not purged from the state apparatus, but remained at the head of the police force, army and judiciary. By granting an amnesty to the fascists, Togliatti’s PCI perhaps reached the lowest point in its history.

Togliatti needed to present the reformist policy imposed by Stalin as an Italian innovation, flowing from ideas first promoted by Gramsci. The Sardinian revolutionary was then presented by Togliatti as a forerunner of the reformist policy of the Stalinist PCI, of the “parliamentary road” to socialism, and of national unity with the bourgeoisie.

Gramsci’s writings were then produced by publishing houses controlled by the PCI, after Togliatti had taken steps to erase from them any elements that did not suit the needs of the Stalinists. Real falsifications were introduced, so much so that the phrase “Trotsky is the whore of fascism,” attributed by Togliatti to Gramsci, actually belonged to Togliatti himself.

The Notebooks from Prison were undoubtedly the text most falsified by the Stalinists, who presented Gramsci’s innovative ideas as an anticipation of the reformism of the PCI. For example, the Gramscian concept of “cultural hegemony”, expressed in the Notebooks, is presented as Gramsci’s abandonment of the revolutionary perspective and therefore an anticipation of a parliamentary path to socialism, which was being followed by the PCI. In fact, anyone carefully reading Gramsci’s writings will understand that the concept of “cultural hegemony” was not at all the abandonment of the revolutionary perspective but an attempt by Gramsci to adapt a Leninist strategy to a Western context. The same concept of hegemony was also present in the work of Lenin.

Gramsci intended to argue that, in advanced capitalist countries, civil society was much more articulate than in Tsarist Russia and therefore the revolutionary movement had to overcome many more obstacles. This necessitated the patient construction of a cultural hegemony of the socialist movement within society, to counter bourgeois hegemony. Gramsci argued that in the West, the road to the socialist revolution would be longer and more complex than in Russia and that it was therefore necessary to fight a “war of position” against capital rather than a “war of movement” as the Bolsheviks had done in Russia. This perspective did not exclude united fronts with other left forces and struggles for democratic goals. For Gramsci, therefore, it was a question of rethinking revolutionary methods in the West, not of renouncing the revolution by joining bourgeois governments as the PCI of Togliatti had done, on the recommendation of Stalin.

Gramsci rejected Bordiga’s ultra-leftism and his sectarian position opposing a united front of the left, but he never proposed any theory justifying popular fronts with the bourgeoisie. Nor did he abandon working class and revolutionary policies. He never argued that in the West it was possible for socialists to take power through parliamentary means, without the need to overthrow the bourgeois state by way of revolution. All of Gramsci’s political battles were directed against reformism. All his ideas and actions contradicted the Stalinist approach.

The fake reformist

Today the bourgeois press, taking up the lies of Togliatti, presents a reformist Gramsci, “Father of the Fatherland” and of the bourgeois Italian Republic. Once again Gramsci is purged of his revolutionary aspects. What does Gramsci, enthusiastic supporter of the Bolshevik revolution, and who in 1920 led the Turin factory council movement have to do with the fake reformist Gramsci presented to us by the bourgeoisie and the Stalinists? The “reformist” Gramsci who promoted coalition with the bourgeoisie never existed, except in the fantasies of Togliatti and Berlinguer. Yet today this is the Gramsci that everyone knows, the Gramsci honored by the bourgeois press, the Democratic Party and the heirs of Stalinism and the Italian reformist left.

Fortunately, in Latin America and in many other countries, the left and the socialists are rediscovering another Gramsci, the Marxist and revolutionary Gramsci. Gramsci was a great revolutionary, who like everyone else made mistakes, but who was always consistent with his socialist ideals. His political heritage belongs to the revolutionary Marxists.