Sarah Moayeri, Flo Klabacher, and Brettros are members of Sozialistische LinksPartei (ISA in Austria).

One hundred and fifty years ago, Rosa Luxemburg (Rozalia Luksenburg) was born in what is now Poland, the daughter of a Jewish timber merchant. The young Rosa became politically active at an early age; at 16 she joined the revolutionary circle “Proletariat” and began to agitate among her fellow students. At this early age, her lifelong activism within the working class had already begun.

She became part of the Polish and German Social Democratic Parties and helped build their left wings as one of their most important figures. She fought within the Second International for a revolutionary course and against attempts to limit the movement to merely “improving” capitalism through the parliamentary road and small reforms. She argued time and again, in opposition to the increasingly ossified leadership of the various Social Democratic parties, that the working-class masses themselves would eventually spring into action and would need revolutionary leadership to achieve their historic goals.

Rosa was repeatedly sentenced to prison for “disrespecting the throne” and her public agitation against German imperialism, as well as the threat of World War 1. But it was not only the ruling classes who feared “Red Rosa” and her comrades, but also those leading social democrats who in the early 20th century increasingly befriended the bourgeoisie and threw socialist principles overboard in favor of privilege and power.

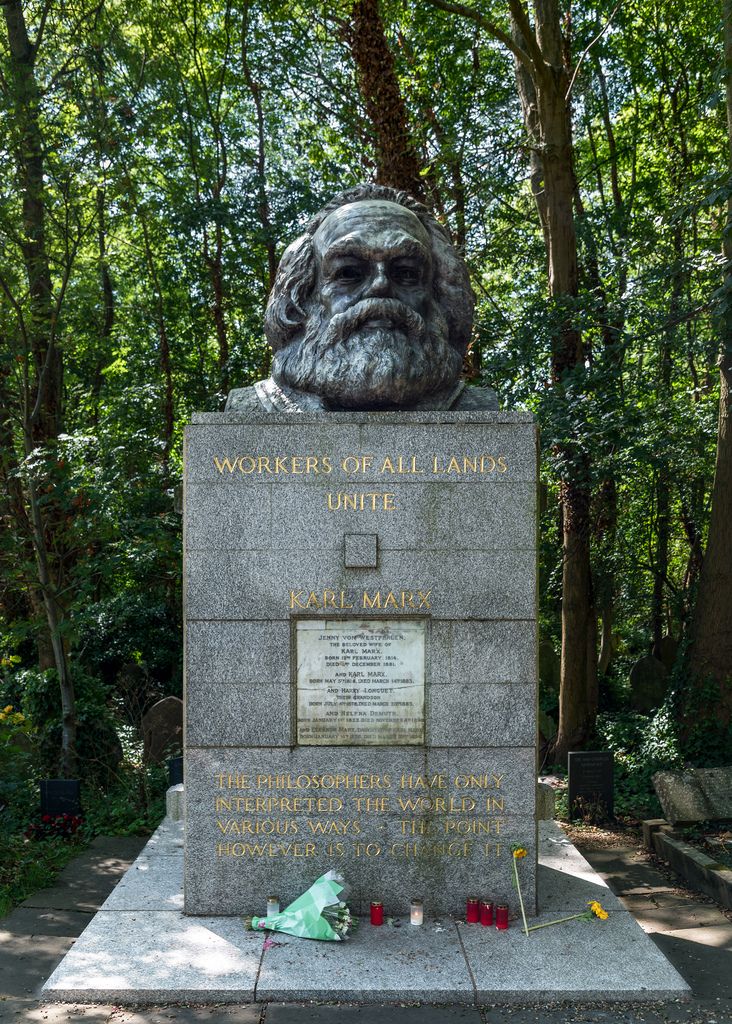

As one of the most important leaders of the German November Revolution of 1918/19, Rosa fought together with Karl Liebknecht and others of the Spartacist League and later of the Communist Party (KPD) for what she had seen in Russia: the successful seizure of power by the working class through workers’ and soldiers’ councils, the expropriation of land, banks and industry through the soviet republic and the first steps in building a socialist democracy. They were only stopped by their arrest and execution on 15 January 1919, ordered by the Chancellor and SDP leader Friedrich Ebert. Rosa’s body was found floating in Berlin’s Landwehr Canal.

Misunderstood Legacy

Rosa Luxemburg’s ideas have lost none of their relevance in the 21st century. With the worsening crisis of the capitalist system, many of her authoritative writings seem tailor-made for our time. Rosa’s work as a revolutionary was always characterized by revolutionary clarity and a deep trust in the working class. The revisionism controversy within Social Democracy expressed this clearly. Rosa argued sharply against Eduard Bernstein and others who, in the face of the economic boom and parliamentary successes of social democracy, were moving further and further away from the goal of a revolutionary upheaval of society. She stood against their arguments that capitalism could simply be reformed again and again until socialism was achieved.

In contrast, Rosa pointed to a path that is still central to revolutionary socialists today: linking the struggle for every improvement in the interests of the working class to the goal of socialist revolution. For her, it was about seeing the struggle for reform not as a primary goal in itself, but rather as a means to help the working class learn how fight for its ultimate liberation through overcoming capitalism.

Today, there is very limited scope for deep reforms within the capitalist framework that could markedly improve living and working conditions. The Corona and economic crises refute all reformist illusions in a more “social” capitalism. Yet all the major left formations internationally have failed in recent years to offer a systemic alternative and have ultimately stuck to raising minimal reformist demands — but without achieving them, precisely because they couldn’t see the bigger picture and the need for struggle.

Rosa explained why capitalism, due to the very nature of private ownership of the means of production, will always produce crises. She described the struggle for reforms as a “school of education for proletarian revolution.” When the working class fights back and wins concessions, this expands its understanding of class antagonisms, the role of the state and above all its self-confidence in its own fighting power.

In practice, this approach to reform and revolution was expressed not only in her rejection of socialist participation in bourgeois governments, but also in her stance in the mass strike debate. Rosa recognized very early on the pernicious character of the bureaucratic trade union and party apparatuses. The trade union leadership and leading social democrats ignored the importance of the spontaneity of the masses of workers. They saw strikes as planned actions, choreographed by the leaderships of the workers’ organizations, which could be used tactically.

But as something that would develop from below and be a central means for the workers’ movement to achieve its goals, the trade union and social democratic leaderships rejected the mass strike. They even repeatedly tried to stifle and ban debates about it within their own ranks. Inspired by her impressions of the Russian Revolution of 1905, and concerned about the inertia of trade union officials and social democratic leaderships, Rosa repeatedly defended the mass strike as an essential tool of the working class. She put it forward as a tactic in situations as diverse as the struggle against the Prussian three-class suffrage system, which heavily weighted the votes of the rich against poor, and the struggle against World War 1.

Rosa argued that social democracy’s orientation toward elections, its limitation to economic struggles led by the trade unions, and its artificial separation between political and economic struggles were doomed to failure. In her view, during revolutionary mass action the “political and economic struggle become one” — a dialectical relationship which is very clear today.

Reform and Revolution Today

The mass movements in various countries that erupted in 2019 and 2020 were characterized not only by the fearlessness and spontaneity of the masses, but also by the inseparability of political and economic demands. Rosa wrote that “where every form and every expression of the workers’ movement is forbidden, where the simplest strike is a political crime, logically every economic struggle must also become political.”

To workers in countries like Iran, China, Belarus, or Russia, this analysis is spot on; the same could be said for the BLM movement in the USA and around the world. But it’s also true in places like France or Chile, where economic struggles quickly became and are continuing to become political. We have seen in the Corona pandemic how economic struggles during a crisis must increasingly take on a political character and vice versa.

Rosa predicted that as larger political struggles developed, labor struggles would also come onto the agenda, and would not wait for “orders” from the union leaders. Many of the major strike movements of recent years have taken place despite the restraining role of the union bureaucracy.

As a small but important example, look at Austria: strike movements have broken out in the health and social sectors in the past two years and have been largely organized from below independently. The union leadership was quite happy to use the outbreak of the pandemic to stifle the movement.

Rosa Luxemburg, while placing a lot of emphasis on the spontaneity of the masses, did not at all underestimate the stalling effect the union bureaucracy, as well as the lack of revolutionary leadership, could have on working-class struggle. In her words: “a consistent, determined, and forward-looking social democracy evokes in the masses a feeling of security, self-confidence and combativeness; a vacillating, feeble approach based on the underestimation of the proletariat has a paralyzing and confusing effect on the masses.”

She saw neither the unions nor workers’ parties as ends in themselves, but recognized even then what is all the more evident today: that without a revolutionary party to organize and direct the anger and activity of the masses toward a socialist alternative, any spontaneity of the masses will sooner or later dissipate and result in defeats.

One of Luxemburg’s most important battles against the dangers of reformism was against the threat of war. She never tired of explaining how the capitalist system inherently creates tensions between the ruling classes and wars between nations. Just like the Bolsheviks, she maintained her staunch opposition to the imperialist war. Meanwhile, the reformist forces capitulated under massive pressure to approve war credits, despite the formal agreement between the parties of the Second International against the war. After a years-long process of gradual degeneration, this capitulation marked the beginning of the rapid end of the Second International. The degeneration of the Social Democracy was symbolically completed with its collaboration in the assassination of Rosa Luxemburg and her collaborator, Karl Liebknecht.

Rosa Luxemburg in the November Revolution

The German Revolution began with the refusal of Kiel sailors to obey orders against a last senseless battle in November 1918. It reached Berlin on November 9th. Rosa Luxemburg was imprisoned in Breslau at the time and only arrived in the capital the next evening. She immediately intervened in the movement — using the program of the Bolshevik Party, which had led the Russian working class to power in 1917.

She demanded the dissolution of the parliament and all political organs of the bourgeoisie, and the transfer of their powers to democratically elected workers’ and soldiers’ councils (soviets); the expropriation of the property of the rich, all banks, mines & large enterprises by the councils; and their subordination to a central body of the workers’ and soldiers’ councils.

Rosa knew the old elites would not give up their rule voluntarily. Therefore, she demanded the disarming of the police and army officers, and at the same time the arming of the working class — i.e., a monopoly on violence by the emerging democracy of councils — to safeguard the revolution. Finally, she called for the revolution to develop on an international basis.

The leadership of the Social Democracy (SPD), on the other hand, worked closely with imperial ministers. The leadership of the USPD (a left-wing split from the Social Democracy) entered into the government with the SPD and prepared for Reichstag elections. This was a decisive step toward disempowering the workers’ and soldiers’ councils.

The following day, Rosa and others refounded the Spartacist League on the basis of the Bolshevik-inspired program stated above. The Spartacists did this now as a clearly defined revolutionary cadre party, in contrast to the loose structure which had existed within the USPD until then. From this refounded party later emerged the Communist Party (KPD). Such a party should, in a revolutionary period, be able to unite the majority of the working class behind its program and lead them to power. Rosa thus drew the same organizational conclusions as Lenin in 1903 — but only 15 years later.

Reformist ideology and the privileges that come from working within the bourgeois system had distanced the SPD leadership so far from revolutionary Marxism that in 1914 they had agreed to the German government’s war policy, instead of organizing a mass struggle against the world war. Rosa, however, had gone to prison several times for her vocal opposition and her role in protests against reformism, war, monarchy and capitalism. Consequently, she had tremendous authority in the working class as the initial war euphoria faded. But she did not use this authority in the early war years to build a powerful organization that could have put its revolutionary program into action.

When the SPD leadership, together with the bourgeoisie and fascist Freikorps, suppressed the revolution of 1918 with force, it became clear that the spontaneity of the masses was sufficient for the struggle for power — but not for victory. Before the October 1917 Revolution, the Bolsheviks had spent 14 years building their organization through detours, mistakes, and personnel changes, training comrades, establishing themselves as reliable fighters in the working class. The KPD, however, was founded only two months after the beginning of the November Revolution and could not decisively influence its course.

Most party members were determined and motivated, but inexperienced in strategy and tactics. They refused to participate in both the elections to the National Assembly and in revolutionary work in the reformist mass unions. Rosa argued to use both these fields of work for party building, but she remained in the minority. Because of this, the KPD couldn’t win over significant sections of the disappointed USPD base and remained isolated from many workers. In the following months, thousands of revolutionaries — among them Rosa Luxemburg — were murdered in uprisings that flared up again and again but were never generalized or coordinated. When the KPD later developed mass influence, it lacked Rosa’s understanding of how to use revolutionary crises to lead the working class to power.

Today, environmental degradation and economic crisis make it clear to many people that capitalism offers us no future, as many new mass movements show. What they lack is an organization and leadership that has internalized the hard lessons from Rosa Luxemburg’s struggles and many other past failed revolutions. This, plus the living experiences of new movements, are the basis for developing a revolutionary program to overcome capitalism in our time. We have made it our task to build such an organization with the ISA.