Tom Costello is a member of Socialist Alternative (England, Wales & Scotland).

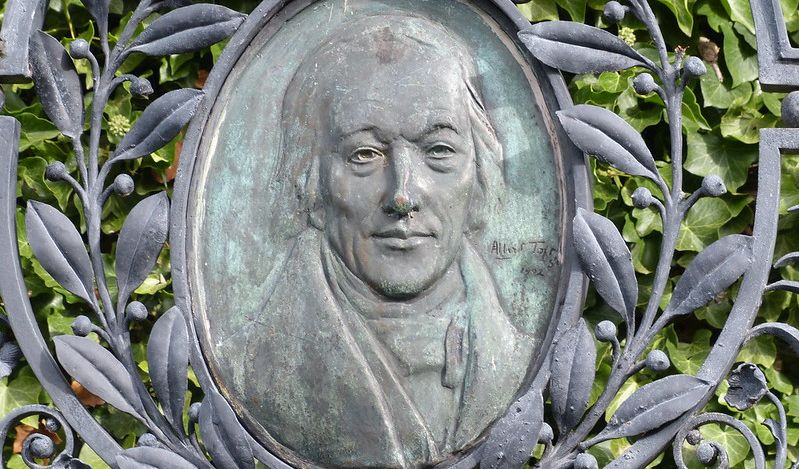

“Every social movement, every real advance in England on behalf of the workers links itself on to the name of Robert Owen.” Friedrich Engels

This month marks 250 years since the birth of a legendary utopian socialist. While today many of his ideas have been contorted into simple philanthropy, what is often overlooked is what he developed. Robert Owen’s radical social vision that provided inspiration for many, itself playing a pivotal role in laying down an earlier foundation for scientific socialism, both in his practise but also in establishing ideas that were pioneering for his time. A full appraisal of the life of Owen is needed to develop a full understanding of the historic significance of Marxist ideas.

Early years

Although Owen eventually acquired a European reputation, his early life was modest. Born in Mid-Wales to a family of skilled tradespeople, his father worked as an ironmonger and saddler.

From the age of nine, he found work in various artisan shops as an assistant, which translated into stepping to the world or business by adulthood. First establishing a small company with three employees in Manchester, his fortunes grew to the point of him taking up managerial roles in a number of factories across the city. Marrying the daughter of a major factory owner in Scotland, he was eventually transferred to ownership of the New Lanark cotton mills outside Glasgow.

In this time, Owen’s thinking already bore the hallmarks of somebody politically advanced, given their class status. This all reflected the conditions of society at the time. Prior to the rise of industry, capitalism had up until this point, been predominantly either small-scale or agrarian in nature. The traditional occupations of rural farming and skilled artisanship were decimated as the last remnants of feudalism were torn down and replaced by newly-developed mechanised production, as a rising urban bourgeoisie began to exercise its power.

Reflecting a changing balance of class forces, many of the established dogmas of earlier periods were being held to the light. Thinkers like Voltaire satirised religion, while atheistic ideas developed in parallel with the rise of the scientific method and materialist philosophy. The natural forces underpinning the world were becoming demystified under the weight of societal change.

For the first time in millennia, social questions were being subject to rational thought. If there was to be no supernatural plan for the world, then why not rationally analyse society? Ideas of humanity having the power to change society to meet human needs emerged as ‘liberty, equality and fraternity’ was drawn on the banners of the French Revolution.

It was this that formed a powerful historical precedent for the development of Owen’s ideas. Although he was not a particularly intense reader, it was through his acquaintances with materialist thinkers that he adopted aspects of John Locke’s argument that human knowledge was derived from the use of the senses.

Owen adopted from the radical reformer Jeremy Bentham a method for measuring the greatest pleasure for the greatest number as a means of understanding the best way to organise society. History was no longer a matter of adhering to “god-given” traditions, but of maximising the good mental and physical development of people across society.

It was no accident that these ideas had come about at this particular conjuncture in history. Poverty, starvation and preventable diseases had exploded under the Industrial Revolution. A landless mass, drawn from the countryside, was increasingly crammed into urban industrial centres, with entire families finding themselves compelled to work to ensure they would make the bare minimum for survival. Those who were without work faced criminalisation under the Poor Laws and shipped off to the dreaded workhouses, where conditions were designed deliberately to terrify the poor.

Owen set out to develop a rational understanding about why this was the case, starting from the then-radical argument that human behaviour was a product of environments, particularly during early years. Rather than accepting the dominant bourgeois idea of the workers’ conditions being the fault of individual character, Owen argued that the poor behaviour, abuse and drunkenness characteristic of “the masses” was not their fault, but of a societal failing to provide the adequate levels of education and means of life.

As he put it in his Third Essay on the Formation of Human Character (1816):

“The character of man is, without a single exception, always formed for him; that it may be, and is, chiefly, created by his predecessors; that they give him, or may give him, his heads and habits, which are the powers that govern and direct his conduct”.

The solution was not to blame the working people for their rottenness, but to enact laws that provide adequate education, and to remove “those laws which leave the lower orders in ignorance, train them to become intemperate, and produce idleness, gambling, poverty, disease, and murder.”

The “enlightened manager”

When Owen first took over at New Lanark, alcohol abuse, crime and poverty was rife. Isolated in the Scottish Lowlands, they were an “idle, dirty, dissolute, and drunken population.”

While it was most common for children to be forced to work 14 hours a day in social conditions that often mimicked slavery, Owen refused to hire children under the age of 10 (to the disapproval of his business partners) and granted the workers the modest improvement of a 10-and-a-half-hour workday, without loss of pay.

In 1806, when the United States declared a cotton embargo on England, Owen paid full wages to the workers for the duration of the four months, again rubbing up against the joint partners who favoured reductions. A sick fund was provided to ensure his workers received medical assistance, constituting a primitive form of private health insurance at a time when basic medical attention was denied to the majority.

This model of “enlightened management” did have an effect on the workers’ lives. As Engels put it in Socialism: Utopian and Scientific (1891):

“A population, originally consisting of the most diverse and, for the most part, very demoralised elements, a population that gradually grew to 2,500, he turned into a model colony, in which drunkenness, police, magistrates, lawsuits, poor laws and charity were unknown. And all this simply by placing the people in conditions worthy of human beings, and especially by carefully bringing up the rising generation. He was the founder of infant schools, and introduced them first at New Lanark. At the age of two, the children came to school, where they enjoyed themselves so much that they could scarcely be got home again.”

This coincided with an entirely new and novel approach to the methods of education. Up until this point, education provision had been deliberately denied to most, to ward off the threat posed by an educated and aware working class. New Lanark’s schools prioritised the development of critical faculties in a rational direction as opposed to restricting itself the sterile practise of enforced “book-learning.” There were also leisure activities — particularly dances, in which Owen invited both parents and children to attend in traditional Scottish dress, which drew the attention (both positive and negative) of neighbouring communities and Owen’s business partners.

Owen the businessman

Owen, in this period, actually embodied the most enlightened and forward thinking section of the bourgeoisie. Very much still of his class, he actively argued for improvements in living conditions on the basis of increasing profitability. The more workers could be somewhat better treated and well-rested, their standard of work and thus profitability, would improve. This was more often than not twinned with an analogy, comparing workers to machines – like machines, care and attention into maintenance and care for conditions of work would lead to fewer malfunctions and, thus, higher productivity. And when asked for evidence, Owen indicated the supposed doubling of profits over his time at the mill.

Owen’s materialism was a vulgar one, predicated on the idea that society was governed fundamentally by reason. If the ruling class could be convinced of this basic calculation, they would be sure to change their orientation. But, as history demonstrates, capitalism is no logical system. What was to work ultimately best for the ruling class would not be necessarily adopted by individual capitalists, who tend to concern themselves with immediate gains and competition over long-term considerations. So while many praised his ideas, he was actually met with hostility from some, including on occasions from his own business partners who, while broadly sympathetic to his thinking, represented more of the majority thinking of the ruling class.

Owen hardly looked towards the workers at all in this period, preferring to curry favour with the “great and good.” He received high-profile visits from a number of royal dukes, clergymen, royals, bankers, economists like David Ricardo and even the former Tory Prime Minister, the Viscount Sidmouth, along with Prince Edward – father of Queen Victoria came to give their blessings. One essay of Owen’s classic work A New View of Society was dedicated to the Prince Regent – the acting monarch at the time. Most notably, Czar Nicholas I – whose grandson was to meet his fate at the hands of the Russian workers a century later, made a high-profile pilgrimage to the site to pay his respects.

What united many of these “high and mighty” figures was their rootedness in old and archaic feudal customs. The Tory party in this period, far from the dominant bourgeois party of today, represented instead the gentry – the landowners whose pretences towards “paternalism” and “fatherhood” gelled well with Owen’s own paternalistic ideas. His vision made attractive viewing for a layer in society who, despite still holding tremendous wealth, had been politically sidelined under the weight and impact of the Industrial Revolution.

Owen’s movement towards communism

Owen’s reception among the industrial bourgeoisie was somewhat more complicated. The industrialists of the time had often sought refuge in philanthropy. If the millowners threw the crumbs from the pie to the poor, this would cancel out the tremendous exploitation and human suffering engendered by the Industrial Revolution.

It was for this reason that “the philanthropic Mr. Owen’s” ideas were originally given serious consideration, with him being invited on a number of occasions to draft up reports to the House of Commons on devising a “cure for pauperism,” in fact laying part of the basis for the Factory Acts.

But at the same time, Owen had begun to draw further conclusions. He had felt at the time that the scheme at New Lanark, although demonstrating some progress, was not sufficient. The example he set was both a case for the capitalists to use to absolve their system of guilt, while also laying a foundation for the workers to consider themselves with a newfound sense of dignity. As the radical Poor Man’s Guardian printed:

“Every working man who read Mr. Owen’s essays become a new being of his own estimation. He no longer feels himself a mere lump of living mechanism, predestined for the use and abuse of others.”

Owen came to describe his labourers as “slaves at my mercy.” Moving beyond simple calls for factory reform, he began to think in terms of radically transforming society, for instance in his rejection of the institution of the church, which he sought to replace with a secular “religion of universal charity.” While this caused strained relations, it was Owen’s move towards critiquing private property itself that irreparably damaged his relations with the bourgeoisie. As Engels later put it in Socialism: Utopian and Scientific:

“As long as he was simply a philanthropist, he was rewarded with nothing but wealth, applause, honour and glory. He was the most popular man in Europe … But when he came out with his communist theories that was quite another thing. Three great obstacles seemed to him especially to block the path to social reform: property, religion and the present form of marriage. He knew what confronted him if he attacked these: excommunication from official society and the loss of his whole social position. But nothing of this prevented him from attacking them without fear of the consequences, and what he had foreseen happened.”

Now, Owen argued, the task of humanity would only come through the peaceful and gradual abolition of exploitation of wage labour. Over just a few years beginning in 1820, he made his departure from bourgeois philanthropy.

What was needed now was no longer model factories, but communal, self-governed “Villages of Cooperation,” in which the rule of financial interest and wage labour would be replaced with communal ownership of property.

Although radical, these ideas were not without historic precedent. Many earlier figures, such as the peasants’ leader Thomas Muntzer ( a leader of Peasant War of 1525 in Germany) and the conspiratorial French revolutionary Babeuf had envisioned a world without private property, which a number of dissident Christian sects at the time had practised communal ownership – not least in England with the Digger movement during the English Revolution. But what was unique to Owenism at this time was in bringing these two strands together. Owen’s vision in this time was that, with the formation of the communities, they would set an example so compelling that others would jump to adopt them, until the capitalist class itself came to realise the error of its ways and choose to abandon its power, phasing out capitalism in the process.

With his earlier reputation shattered, Owen began to look elsewhere, eventually settling instead in the United States. Here was a society in which there was both vast expanses of land, but also an atmosphere of relative toleration to his schemes. In 1824 he finally departed, severing his decades-long attachment to New Lanark.

Purchasing the village of Harmony, Indiana from the Rappites (a small communal Christian sect), he quickly christened it New Harmony. The settlement’s new constitution declared that it would be governed by general councils – internally by all those residents aged between 30 and 40, and externally by those aged between 40 and 60.

Until then, Owen was to run the community as his property as its “guardian.” All aspects of living were to be done communally. Childrearing was declared a collective task, and the proceeds of work and money were to be shared in common, in accordance with productive labour.

Like all other attempts at implementing these utopian communities however, New Harmony was ultimately a failure. Owen’s idealism clashed with the material reality of American society. And true to his style, Owen chose to blind himself to it. He dismissed the importance of economic arrangements, instead relying on a combination of wealthy donors (including himself) and his own moral determination to mould his subjects in his own image.

But, unlike at New Lanark, the residents of New Harmony were not “slaves at Owen’s mercy.” The fact that his workforce in Scotland, like the entire working class, lived in fear of unemployment compelled them to act in accordance with Owen’s personal schemes. With this removed from the equation, bending reality to Owen’s will became a much harder task.

By turning the community into a voluntary association, a very different sort of social arrangement came about. Those who came over to New Harmony were a mass of pauperised labourers, deprived of work in the midst of an agricultural recession. Many forced into criminality, these layers had none of the social commitment that Owen had expected, but instead sought unemployment relief, turning the community less into the utopian paradise Owen foresaw and something more akin to a soup kitchen.

This instantly posed limitations on what New Harmony could actually achieve. Owen’s attempt to institute a public cash box, whereby money was pooled to be taken and paid into at will, was looted by those who needed quick cash to effectively survive.

When Owen tried to supplement his charitable behaviour by propagandising his views on marriage and religion, he was quickly rebuffed by those who were not prepared to give these up.

As the communal dining halls fell into disrepair and communal houses were sold off, the community began to split into different directions, with some travelling elsewhere in America to establish their own attempts at forming communes – all of which failed in a short time.

Owen’s turn to the labour movement

Having lost 80 percent (around £26m) of his fortune on this venture, Owen departed back for England in 1827, leaving sole ownership of the village in the hands of his sons.

In his absence, Owen’s followers back home had made steps forward of their own accord. More and more, a generation of ‘Owenites’ began to ask themselves, if Owen’s system for harmony and cooperation – of establishing societies on the basis of common need was so self-evidently good, why couldn’t the workers fight to establish it themselves, without relying on funds and support from “benevolent” capitalists? If human nature was ultimately malleable through education, why couldn’t the workers educate themselves in establishing new traditions of struggle?

Seismic shifts had taken place in society. In its formative stages, capitalist England had been highly reliant on the existence of a class of artisans, often making use of primitive technology to produce goods from a highly skilled and specialised standpoint. Production of goods was the preserve of those who worked in small shops, working largely by hand. Industrialisation destroyed this. The creation of new industrial technologies rendered a growing layer of artisans impotent, feeding into the growth of an impoverished industrial proletariat that swelled in size. Unlike before, by 1830, the Industrial Revolution had begun to exhaust its own potential for further development, ushering in an epoch of capitalist stagnation.

In parallel with the artisan societies, workers’ combinations came into existence, often operating in secret out of fear of punishment from both the state and employers. Many “trade unions” would not be considered that by today’s definition, with many operating more as mutual aid societies for workers to come to each other’s support. But the simple principle that working people could organise to address their own interests proved incredibly powerful

The 1799-1800 Combination Acts had severely repressed trade unionism, often under the guise of opposing intimidation.” Following their partial repeal in 1824, new opportunities for organisation were seized. From witnessing the industrial working in a passive position, Owen upon his return saw that, in just half a decade, a nascent workers’ movement had taken shape, with many of the movement’s central leaders inspired by his ideas. Workers facing lockouts began turning to the setting up of ad hoc co-operatives as a means of providing relief and solidarity with workers in struggle.

It was in this context that Owen felt increasingly compelled by events to undergo a sharp change in political direction. His earlier ideas would no longer cut it in this changed situation, as was reflected in the staunchly critical comments of the radical Poor Man’s Guardian editor Henry Hetherington:

“To establish even partially, upon independent grounds, any of Mr. Owen’s philanthropic views in the present state of the country, and before the working classes are politically emancipated, is only putting the cart before the horse, and will end in an abortion. (December 1831)

He was thus left with little choice but to describe the workers’ formations as the model for a future society, which in turn was an attractive vision for the new army of proletarians that had been forced into the factories, which led him to establish “Equitable Labour Exchanges” to create a parallel market free of capitalist middle-men.

The idea of general industrial trade unions took shape in this period – first in Manchester, where the cotton spinners’ union organiser John Doherty issued calls for the formation of a “union of all trades” embracing labourers across sectors. This eventually culminated in the formation of a single Grand National Consolidated Trade Union (GNCTU), with Owen playing a supporting role. Rather than simply organising for changes like the 8 hour day, there should be preparations for a “grand national holiday,” whereby workers down tools, he argued. Under the pressure of the general strike, capitalism as a system of exploitation would be brought to its knees, followed by the reconstruction of all trades along co-operative lines, in effect transforming society into a national version of the communist colonies Owen had attempted to build in American previously.

Money as such would be replaced by a system of “labour tokens,” whereby currency was measured according to the necessary labour going into products, which would allow for trading to operate on an equal basis.

Hitting a brick wall

These ideas, prefiguring the ideas of syndicalism, represented a major advance for the time. Owen had partially succeeded in finding a route through which he could fuse his utopian ideas in part with elements of the emerging movements of the working class.

Where Owen preached these ideas, he gained support and recognition from a layer of advanced workers who had been grasping for answers as they moved towards getting organised. This was particularly the case during Owen’s brief period of building solidarity campaigns for the Tolpuddle Martyrs. These were a group of six in Dorset – dissenting Christians who had formed a Friendly Society of Agricultural Labourers under conditions of strict secrecy. Convicted of “swearing to illegal oaths,” they were deported to Australia initially for life imprisonment. Placing himself at the head of efforts to secure their amnesty, Owen led a giant march to the House of Commons to demand freedom.

Although this resulted in the Tolpuddle Martyrs’ release two years later, Owen’s brief relationship with the workers movement had begun to run its course. One ‘Owenite’ union, the Operative Builders, having led strikes and sit-downs under the demand for workers’ control of construction, had begun to face employers’ lockouts – most famously in Derby, where workers had effectively been starved into signing documents renouncing their union. This employers’ offensive, backed by the repressive power of the state and its anti-labour laws, had a certain disorientating effect on the movement, but more than anything on Owen himself.

While developing in the direction of class independence, Owen had never relinquished his anti-revolutionary idea that through moral appeals, the capitalists would be compelled to voluntarily relinquish control over the economy on a gradual basis. Despite his slogans, he still did not think in class war terms, as was seen when Owen removed J.E. Smith as editor of the Owenite journal The Crisis for advocating class struggle to achieve Owenite aims.

His class collaborationist and idealist approach clashed harshly with reality. And, rather than facing up to it, he moved to wind up the GNCTU, just a mere four months after his march on parliament.

Later life

In search of comfort and familiarity, Owen reverted quickly back to establishing his isolated “Villages of Cooperation.” In 1839, he purchased a patch of land in the village of East Tytherley in Hampshire, where he constructed a large, three story building (Harmony Hall) to try out his new venture. Such attempts, along with those in Orbiston in Scotland and Ralahine in Ireland all failed in much the same way that New Harmony did. While the working class in Britain was moving towards revolutionary demands for democratic rights in the form of the Chartist movement, Owen abstained from these popular struggles, retreating into sectarian thinking, establishing a naively-titled “Association of All Class of All Nations,” through which he could rally his personal followers.

This is not to say that Owen’s lifetime contribution had no effect, as can be seen in the activity of his descendants and followers. One son of his, Robert Dale Owen, was elected in his time to the Indiana state senate, where he campaigned for reforms benefiting women, for instance in freeing up divorce rights.

His partner Frances Wright herself carved out a reputation. Early on a political follower of Owenism, she traced Owen’s ideas onto the conditions of US society, becoming a tireless campaigner for the abolition of slavery, but also other radical ideas such as birth control and sexual liberation, taking from Owen his attitude of opposition to established religion. Most importantly, the efforts of the junior Owen and Wright resulted in the formation of the Workingman’s Party: an attempt at establishing an independent working class party in New York City that, while ultimately not successful, served as an inspiration for subsequent generations.

Owen’s ideas maintained relevance in terms of the enduring influence they had on later movements of the English working class. In spite of his abstention, many of those who rose to prominence in Chartism came of age as young ‘Owenites’.

Many of those who had joined Marx’s International Workingmen’s Association (First International) themselves were either Chartists, trade unionists or Owenites, who Marx gave credit for inspiring many of the ideas of co-operation that became the zeitgeist of the European Revolutions of 1848. As he put it in his Inaugural Address to the International (1864):

“The value of these great social experiments cannot be overrated. By deed, instead of by argument, they have shown that production on a large scale, and in accord with the behest of modern science, may be carried on without the existence of a class of masters employing a class of hands… In England, the seeds of the co-operative system were sown by Robert Owen; the working men’s experiments, tried on the Continent, were, in fact, the practical upshot of the theories, not invented, but loudly proclaimed, in 1848.”

Birth of Marxism

Most importantly, Owen’s historic contribution was in preceding and contributing to a theoretical groundwork for the emergence of Marxism.

Marx and Engels had a lengthy relationship with this movement through their lives, often wavering between competition and co-operation with them in this period. In the predecessor organisation of the Communist League (which Marx and Engels wrote their famous manifesto for), the ideas of utopian socialism held sway over scientific socialism for a whole period of the organisation’s existence.

Engels travelled to Manchester in 1842 at the behest of his father to help run the family factories, and also he threw himself into the developing Chartist movement, as well as writing for the Owenite journal, New Moral World.

Marx equally shared a common lineage with Owen in both of their influences being derived from radical bourgeois enlightenment thinking. Common to both was an appreciation for the method of relentless criticism of existing society. The context of the time was described by Engels:

“Every form of society and government then existing, every old traditional notion, was flung into the lumber-room as irrational; the world had hitherto allowed itself to be led solely by prejudices; everything in the past deserved only pity and contempt.” (Socialism: Utopian and Scientific).

Marx was particularly an admirer of Owen’s educational efforts, in overturning the idea that the working class, by virtue of its social position, ought to be kept ignorant. In this, he conceded, the works of Owenism and other strands of utopian socialism were “full of the most valuable material for the enlightenment of the working class.”

Owen’s educational ideas, Marx said, represented the “germ of the education of the future” – a small constituent part of what was to come into existence at a later stage. Central to a Marxist understanding of Owenism was in neither crudely denouncing nor entirely accepting the dogmas guiding Owen’s life, but objectively appraising and recognising both its monumental contributions and drawbacks.

Understanding Owenism

Marxists always try to understand political trends in terms of underlying social relations. Political trends, even among the left and the socialist movement, for instance, tend to reflect the interests of different classes. In this, Marx and Engels came to argue that Owen’s ideas represented the interests of sections of the bourgeoisie and petit-bourgeoisie who had broken ranks with the dominant ideas of their class, owing to the failure of the enlightenment and bourgeois revolutions to deliver on their promises to create a “world of reason.”

At the same time, Owenism came of age in a period of immaturity. Where the industrial working class, still only in a formative stage of existence, was yet to show its ability to struggle for and create a fully liberated, socialist society.

As Engels put it: “To the crude conditions of capitalistic production and the crude class conditions correspond crude theories.” The route towards liberation of the mass of people under capitalist rule was vague and ill-defined as a result. “The solution of the social problems, which as yet lay hidden in undeveloped economic conditions, the utopians attempted to evolve out of the human brain.” (Socialism: Utopian and Scientific).

Engels thus joked that, in Owen´s mind, socialism only was yet to exist because nobody had thought of it yet. If it was only desired by enough people, we would get there! This, twinned with Owen’s class collaborationist appeal to all classes in society was what fundamentally marked it out as utopian:

“They considered themselves far superior to all class antagonisms. They want to improve the condition of every member of society, even that of the most favoured. Hence they habitually appeal to society at large, without distinction of class; nay, by preference, to the ruling class. For how can people, when once they understand their system, fail to see it. It is the best possible plan of the best possible state of society. Hence, they reject all political and especially all revolutionary action; they wish to attain their ends by peaceful means, and endeavour, by small experiments, necessarily doomed to failure, and by the force of example, to pave the way for the new social gospel” (Socialism: Utopian and Scientific).

This explained Owen’s increased divorce from material reality. While he was creating experiments that often fragmented along class lines (such as at Harmony Hall where the community split between wealthy donors who demanded control and workers who demanded democracy), the real historic movement of the working class was happening in his absence. While Owen was setting up the Association of All Classes of All Nations, the bourgeoisie was responding with violent repression in the face of the workers’ democratic demands!

Marxism

Compared to Owen’s early years, the rapid expansion of capitalist industry in Marx and Engels’ youth provided a very different backdrop. This was a period where both democratic and trade union rights were being pushed across Europe, not by moral appeals, but by the ongoing struggles of the working class. The revolutionary socialism of Marx and Engels was, as a result, thoroughly democratic and saturated with the belief in the ability of the working class to take control of society – not just to be “educated” by elite philanthropists.

Owen saw it as his personal moral duty to instil what he perceived to be the perfect enlightenment values (in reality, his own) into his workers through coercive and elitist means. Bans on pubs and extra-marital sex were instituted at New Lanark, for instance, along with the introduction of military drills to instil “erect and proper form, and habits of attention, celebrity and order.” Marx flipped this on its head, moving away from Owen’s claim that the workers are “too ignorant and inexperienced to find a remedy to the existing evils,” instead proclaiming that “to conquer political power has therefore become the great duty of the working classes.”

The new scientific socialism was not a quasi-religious cult-like movement of Owenism (particularly in its later years), but the “real movement which abolishes the present state of things” by standing with the working class in all its own struggles, advancing demands on prevailing powers to both expose the workings of the capitalist system but also to raise the confidence and awareness that the working class has of its own power.

“The working class have no ready-made utopias to introduce by decree of the people. They know that in order to work out their own emancipation … they will have to pass through long struggles, through a series of historic processes, transforming circumstances and men. They have no ideals to realise, but to set free the elements of the new society with which old collapsing bourgeois society itself is pregnant.” (Marx, The Civil War in France, 1871).

Owenism today

We should recognise the historic contribution of Owenism. For all of its clear weaknesses, what it represented was an early vision of an alternative to capitalist chaos and misery. His ideas energised many and helped pave a way for millions to draw increasingly radical conclusions, giving him a legacy that extended long past his lifetime. But Owen’s vision of a co-operative, free society based on collective ownership and mutual respect, like the ideas of reformism today, clashed irrevocably with the reality of capitalist production and capitalist social relations due to the absence of a clear, class-based and revolutionary method for its creation.

Marxism is equipped to understand how the conditions of Owen’s life determined his ideas. Marxists understand that the ideas of individuals – even great individuals like Owen – are never truly static. The changing balance of forces, of a growing industrial working class, increased monopolisation and development of industrial capitalism affected Owen’s politics, sometimes pushing him in the direction of spearheading events, but more often than leading him to run up against the tide of radicalisation, held down by conservative ideas rooted in his own class position.

It is precisely for this reason that the historical lessons of the radical life of Robert Owen are important. We recognise the world-historic contribution he and his ideas represented. The central idea to Owenism – that “human nature” is not unchanging and fixed – remains essential for socialists today as we recognise the ability of workers and youth to change society. He left an indelible imprint on the development of revolutionary ideas, even if subsequent methods of analysis have followed it today.

We in ISA argue that socialism today is possible, owing to the growing size of the working class and the readiness of youth to fight back. But it is also a burning necessity. Capitalism´s multiple crises, relating to the climate, public health and inter-imperialist rivalries, makes learning from our past more important than ever as we build an international revolutionary socialist movement to transform society.