Interview in 2004 with ISA member Laurence Coates, full-time Militant organizer in Liverpool in the 1980s.

It is 40 years since the legendary Militant-led city council was elected to power in Liverpool, then Britain’s fifth largest city. On 5 May, 1983, Labour won the local elections in Liverpool, gaining 12 seats with a 40 percent increase in the Labour vote. This was a startling exception to the national trend which benefited Margaret Thatcher’s Tory government.

The Labour Party in Liverpool was led politically by the Trotskyist Militant Tendency, from which International Socialist Alternative (ISA) and our section in England, Wales and Scotland trace our roots. The electoral victory in Liverpool, based on socialist policies and refusal to accept the Tories’ job destruction and austerity, laid the groundwork for one of the most important working class struggles in Britain at the end of the 20th century.

How is the Liverpool struggle relevant today?

It shows what’s possible when you have a party and a leadership which wages a real fight in defence of workers’ interests. At that time, like today, local governments were carrying out a mix of cuts, privatisation or raising local taxes to compensate for cuts in central government grants. This was neo-liberalism before that term was even invented. But Liverpool was different.

The City Council, whose policies, program and crucially whose tactics in the course of the struggle, were determined by the strength of Militant in Liverpool, refused to carry out the cuts demanded by Thatcher’s government. Contrary to the myth put around by our critics — that Marxists only participate in struggles and campaigns they control — the council Labour group in Liverpool included Labour lefts and even sections of the party right-wing. In fact, Militant comrades were always in a minority numerically, but our policies and proposals for action carried the day in most cases.

Today, parties of the “left” in most countries have become budget fundamentalists: insisting on balanced budgets and even surpluses. Marxists don’t advocate deficit financing within a capitalist economy as a strategy, our alternative is state ownership and democratic planning of the major companies and banks. But in the context of local government, we argued that Liverpool should set a deficit budget, whereby income would not cover planned expenditure, and then launch a mass campaign to force Thatcher’s government to provide the extra resources.

Labour won the council elections in Liverpool in May 1983 against the national trend on a completely different program to Labour in the rest of the country.

Different in what way?

For a start, Liverpool’s Labour council actually carried out its election promises. It promised to reverse 2,000 job cuts pushed through by the previous Liberal-led administration, which it did. The Liberals who’d run the city together with the local Tories for ten years had also put a complete freeze on council house building.

We launched an ambitious program to build 5,000 new homes which in the next four years would see Liverpool build more council houses than all the other local authorities in Britain put together. This led to the creation of 12,000 new jobs in the building industry. It should be remembered that male unemployment in Liverpool at that time was 25 per cent. Youth unemployment was up to 90 per cent in some parts of the city! As for housing conditions, even Thatcher’s minister Jenkin, when he visited the city for negotiations in 1984, admitted that he’d never seen anything like it — he was shocked.

We raised the minimum wage of council staff to 100 pounds-a-week (an increase for the 4,000 lowest paid) and cut the working week from 39 to 35 hours without loss of pay. The city council with over 30,000 workers was the biggest employer in the region. The council workers’ trade unions, a decisive part of the struggle, had an unprecedented degree of control, including the right to nominate half the candidates for new jobs.

We used to joke that we revolutionaries were the only “reformists” still around. We could point to the spectacular reforms in Liverpool, won through struggle, and counterpose this to the record of the reformists at the head of the Labour Party who’d abandoned any serious commitment to reform in the interests of the working class.

The social democrats claim that “the Trotskyists drove Liverpool to bankruptcy”.

That’s just a lie! It was Thatcher’s government whose policies nearly bankrupted Liverpool. Thatcher’s cuts to the grant allocation system meant Liverpool had lost as much as £34 million since 1979 (when her government came to power).

The Tory government’s idea was to force locally elected politicians to make big cuts. In Liverpool’s case, if we’d followed government orders, our first budget in 1984 would have been 11 per cent smaller than the 1980–81 budget. It would have meant sacking 6,000 council employees to balance the books.

While the national Labour leaders opposed Thatcher in words, in practise they did nothing. They told Labour councils “whatever you do, stay within the law”. The legal position of local councils is that they can be fined and disqualified from office if they wilfully fix a budget in which income and expenditure don’t balance each other out. The Liverpool councillors said we’re not lawbreakers, but it’s better to break the law than to break the poor.

So where was the money going to come from? Militant was opposed to raising the rates (municipal taxes) …

At that time, many Labour councils did raise the rates, massively in some cases, to avoid making cuts, but this played into the Tories’ hands, undermining Labour’s support. We said this is not an alternative because of course this also hits working class families. We have the same argument today when this dilemma is posed in many countries and local administrations. We’re against local tax increases to compensate for government cash limits. The alternative is to fight for more resources.

Anyway in 1984 Thatcher introduced a new rate-capping law which imposed fines on councils if they raised the rates beyond a certain limit set by the government. This closed off this supposed escape route. In Liverpool the position we adopted was that a smaller rate increase, in line with the rate of inflation, was alright, as was an increase to finance a genuine expansion of council services. But under no conditions just to fill the hole caused by government cuts.

The City Council, and particularly Militant supporters like Derek Hatton and Tony Mulhearn, who were the main leaders of the struggle, explained that Thatcher’s government had stolen millions of pounds worth of state grants earmarked for Liverpool and other cities. “Give us back our £30 million” became a rallying cry of the movement, entering the consciousness of the population as a whole.

An opinion poll in the Daily Post (24 September 1985) showed that 60 per cent — in a city of half a million — supported the demand for more money from central government. Only 24 per cent disagreed. In the same poll, 74 per cent said they were prepared to put up with disruption in services like schools, refuse collection etc. in the event of a council workers’ strike to support the council. Bear in mind there was a hysterical scare campaign against Militant and Liverpool from the government, the media and later from the national Labour leaders. On more than one occasion Thatcher threatened to suspend local democracy in Liverpool and send in the army. Yet we succeeded in winning the hearts and minds of the working class of the city.

How did you build such support?

The right-wing in the Labour Party always argued that the program and ideas of Militant, of Trotskyism, could never get mass support. Our “extremism” would scare people away, they said. In Liverpool we succeeded in showing who the real extremists were — Thatcher and those pushing for cuts. Of course, they attacked us as extremists. But as one letter to the local paper showed, people shrugged this off. This letter said: I’m not sure who Leon Trotsky was but he must have been a bricklayer judging from how many houses Liverpool has built!

We always understood that the struggle had to move from the parliamentary arena — from the council chamber — into the streets, the workplaces and housing estates. Only by mobilising the working class behind the council could we force Thatcher to give way. On Budget Day 29 March, 1984, for example, we organised a one-day general strike.

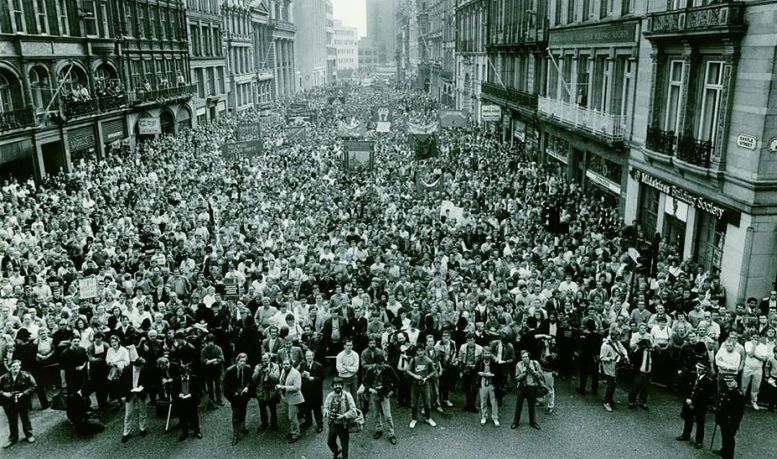

This was, “one of the largest city-wide general strikes in British history” according to Peter Taaffe in his history of the struggle, Liverpool a City That Dared to Fight, co-written with Tony Mulhearn. 50,000 marched on the Town Hall that day to support the council’s stand. From this point onwards there was no doubt that the council’s strategy — refusing to cut or implement excessive rate rises — enjoyed mass support. The Liverpool Echo, which was as hostile to the struggle as the rest of the capitalist media, carried a picture of the giant demo on its front page with the headline “March of the Masses”.

How was such a huge mobilisation possible?

The strike and demo were the fruit of months of campaigning: mass meetings all over the city, factory gate meetings, canvassing and leafleting. We knew we couldn’t rely on the capitalist media to report our position correctly. In the run up to Budget Day the Liverpool Labour Party distributed 180,000 copies of its own newspaper ‘Not the Liverpool Echo’. While we were doing this, the national Labour leaders were urging Liverpool to increase the rates by 60 percent instead of fighting.

Did you believe it was possible for one city to win on its own?

No, we took concrete steps to build national and even international support. Comrades from all over the world came to visit and help out. After the tragedy at Heysel Stadium in Belgium (when 38 Juventus fans were killed when part of the stadium collapsed during a football match against Liverpool FC), the council leaders contacted workers’ organisations in Turin and organised an official visit to discuss the problems facing workers in the two cities. This was in the face of a vicious national media campaign alleging among other things that Liverpudlians were violent people and this was thanks to Militant!

We had particular success forging links with council trade unions in other cities, especially London. Representatives from Liverpool addressed meetings around the country. Militant organised a number of really big meetings. The victory in Liverpool on 9 June, 1984, when the council won concessions from the government worth £16 million, was due in part to the miners’ strike which had started three months earlier.

Thatcher knew she couldn’t fight on two fronts and decided to concentrate on the miners. Some left critics — notably the Socialist Workers’ Party who called it a “sell out” — attacked us for reaching a deal. This was never the attitude of the miners themselves who saw our victory as a tremendous morale boost. After all, we’d proven that Thatcher could be beaten if the working class had a determined leadership and the right program and tactics.

Having won significant concessions, it would have been almost impossible for us to simply reject the government’s offer and carry on the struggle. In that case, workers in Liverpool would begin to suspect the Tory propaganda was true, i.e. that Militant had a hidden agenda: confrontation at any price.

Weren’t there tensions with the other groupings in the leadership of the campaign? How did you maintain a united front?

Eventually, when the national Labour leaders waded in using Stalinist methods and closed down the local Labour Party, splits did open up. But in the first phase of the struggle, 1983–85, the pressure of the masses behind our demands and our campaign strategy meant that the critics kept a low profile.

We showed that it’s possible to weld together a mass movement, a very broad movement, behind the fighting slogans and methods of Marxism. This is relevant today when we’re accused by some of scaring away potential support, of being “too political”, for example in anti-war and anti-racist struggles.

This type of criticism recalls what the Stalinist Communist Party did in Liverpool. From the side lines they claimed that Militant’s “sectarianism” was limiting the scope of the movement. They wanted a broader alliance to include the Church, right-wing Labour leaders and even sections of the Tory Party. In the end the Stalinists got their alliance with the Tories and the Labour leaders — against the council, against the mass struggle and against the gains of the 1983–87 period.

How did the ruling class react to the successes of the struggle in Liverpool?

Thatcher couldn’t defeat Militant and the Liverpool City Council by democratic means. We’d won every election in that period. In the 1983 general election, 47 per cent (128,467) of the city voted Labour. This rose to 57 per cent (155,083 votes) in the following general election of 1987, after four years of intensive struggle.

The Liverpool 47 — the 47 Labour councillors who took the fight to the very end — had to be removed by a judicial coup in the House of Lords, a relic of feudalism! This, incidentally, is why the capitalists hang on to undemocratic institutions like the monarchy and the House of Lords.

But this was only made possible by an alliance between Thatcher and the national Labour leaders against Liverpool. Over half a million pounds worth of fines and legal costs was imposed on the 47, money which was raised through collections in the working-class movement.

While we were fighting the Tories, the Labour leader Neil Kinnock launched a second front against us. The Liverpool Labour Party was closed down, then restarted under a police regime. Militant members were expelled and barred from standing as candidates. This was accompanied by an unprecedented campaign of slander.

Incidentally, Kinnock — who accused us of undemocratic methods and corruption — later went to the European Commission in Brussels, which was collectively sacked in 1999 after a massive corruption scandal. Kinnock, who claimed that his “moderate” approach was needed to get a Labour government elected, never won a general election as party leader, and is largely only remembered for his 1985 conference speech in which he slandered Liverpool and the Militant in true Stalinist style. Think that people like this stood in judgement on the Liverpool councillors whose only crime was to fight for jobs and services.

What effect did these attacks have in the trade unions?

The moves against Militant in Liverpool marked the beginning of a political counterrevolution inside the Labour Party which eventually, under Tony Blair, turned it into an out-and-out capitalist party. There were pockets of opposition to our policies from the outset from careerists and Stalinists, but these elements were very isolated. When Kinnock and the entire establishment turned their fire on Militant and the City Council they found their courage.

One issue which emerged was the opposition of the so-called Black Caucus — a middle class group who saw themselves as the leaders of the city’s black community. This group became a cause célèbre of the Labour right-wing and the media. None of them of course were interested in the opinions of the black council employees and union activists who played a key role in the mass struggle. Some sections of the trade union bureaucracy in Liverpool supported and encouraged the Black Caucus.

This group’s attacks on the council, over its appointment of Sam Bond, a Militant supporter, as the council’s Race Relations Officer, were used by Kinnock to try to split and confuse the movement, to smear the council as racist or at best ‘colour blind’ towards the special oppression of people of colour. This lie is refuted by the council’s record on employment, housing and anti-discrimination policies which represented important progress for the black community.

The Stalinists, while numerically tiny in Liverpool, had one or two important union positions. Instead of mobilising their organisations behind the struggle, they used their positions to attack the council. They played a particularly destructive role in the leadership of the teachers’ union, narrowly getting the teachers, many of whom lived outside the city, to vote against participating in coordinated strike action in support of the council in 1985. This was a major setback in the struggle.

How was the Liverpool struggle eventually defeated?

The background to the battle in 1985 was different to 1984. The miners’ strike had been defeated due mainly to the scandalous role of the right-wing Trade Union Congress leaders who refused to organise effective solidarity action. Thatcher wanted revenge on Liverpool — to extinguish the idea that militancy pays (“if we fight, we can win”).

In the interests of a united front with 25 other “left” labour councils against rate-capping we accepted a tactic which we ourselves had big reservations about: the so called no rate-tactic whereby the councils all agreed not to set a rate, and therefore a budget, as a protest. Liverpool had argued for setting a deficit budget instead, a tactic similar to 1984 when Liverpool fought alone, because this was easier to explain to the public and mobilise behind.

This episode just goes to show how we approach the question of the united front. Militant and the labour movement in Liverpool bent over backwards to reach an agreement for common action with the other Labour councils. If we hadn’t, of course, we would have been attacked for sectarianism, refusal to cooperate etc.

This united front however fell apart almost immediately, with one Labour council after another abandoning the no-rate-tactic. Liverpool was left to fight alone (with only Lambeth in London staying in the fight). We knew the position wasn’t as favourable as it had been a year earlier. At the same time there was no alternative but to fight — apart from making cuts.

When our call for an all-out strike of the council workforce was narrowly lost in September 1985, as a result of sabotage by sections of the union hierarchy, we were in a very difficult position. Even so, the tactics employed — for example by dragging things out in the law courts — kept the 47 in power for another one and a half years until March 1987.

This in turn ensured that Liverpool’s housing program, for example, wasn’t overturned by the return of the Liberals and Tories. In some ways I think our enemies were even more taken aback by the tactics employed in this period, a period of retreat, than they had been during the movement’s ascendancy. This was acknowledged by Michael Heseltine, the chairman of Thatcher’s Tory party, when he said Militant was “the organisation which never sleeps.”

The new generation needs to learn these lessons. Liverpool showed that the working class can defeat a seemingly unstoppable neo-liberal offensive. In decisive battles a clear fighting program is needed, organisation, roots in the working class, and last but not least a leadership that strives to seriously measure up to the enemy, anticipate its attacks and respond with tactical flexibility. To achieve this, we need to build a Marxist party and solid organization with mass support.