Arne Johansson is a member of Socialistiskt Alternativ (ISA in Sweden).

When the CWI, the Committee for a Workers International, was formed in the upstairs of the Mother Red Cap pub (an old pub said to have been frequented by Karl Marx, rebuilt in the 1980s and ironically renamed World’s End) in London on 20-21 April 1974, exactly 50 years ago, the ambition was to sow the seeds of a new, revolutionary workers’ international that could challenge capitalism on a global scale in the foreseeable future.

This article focuses on the ideas and conditions that motivated the formation of the CWI and are still worth building on today.

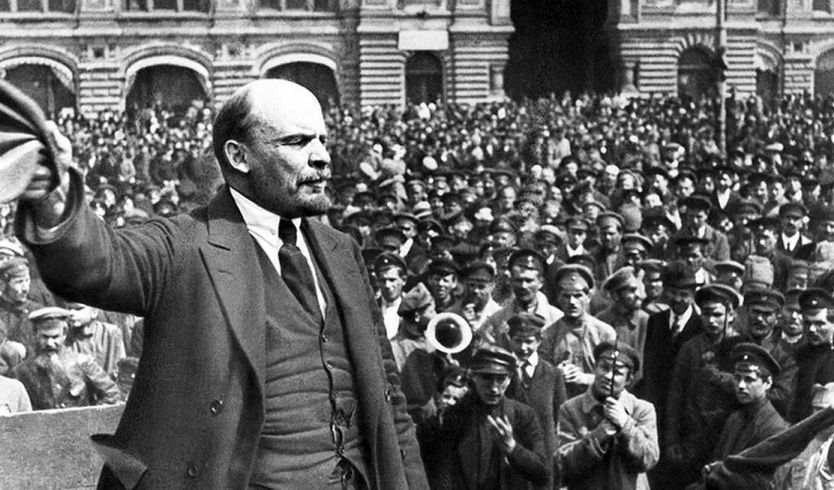

Those of us who participated wanted to reconnect with the best theoretical and political legacy of the First, Second and Third Internationals since Marx and Engels and the Russian October Revolution. Likewise with Trotsky’s struggle for a new Fourth International after the Russian Revolution degenerated completely and the Stalinist Moscow-controlled Third International also failed to build powerful united fronts that could have stopped Hitler’s rise to power and won the Spanish Revolution.

The formation of the CWI meant a theoretical confrontation with the other groupings that also saw themselves as Trotskyists but were completely wrong in their uncritical idolisation of the charismatic leaders of the colonial revolution, their lack of faith in the working class and their view of students and intellectuals as the new avant-garde.

Behind the launch was above all the group around the Militant newspaper in the British Labour Party, whose leading theoretician Ted Grant had been an active Trotskyist since the 1930s and whose young members in 1970 had won a majority in the LPYS, the British Labour Party’s then small but rapidly growing youth league.

This also opened up new opportunities for contacts with young Marxists and individuals from other countries, who were usually active in the youth organisations of various social democratic parties.

Swedish comrades have previously described how we, who published the first issue of the Marxist paper Offensiv in September 1973, came into contact with two British visitors from the LPYS at the 1972 SSU (social democratic youth league) congress, where heated debates took place between the right wing leadership and critics from the left.

At the founding meeting of the CWI in London, I was one of 46 participants from 12 countries. I represented a small group in the north of Sweden, who, after intensive discussions with comrades from Militant, had clicked with the ideas. The fact that our then only stencilled magazine Offensiv was met from the start with positive reactions among radical SSU clubs throughout the country, locally even at the grassroots level of the Social Democratic Party, also contributed strongly to us being on board. The background was similar among other participants from Ireland, Germany and other European countries.

Even before the formation of the CWI, we were all strongly influenced by the radical winds that blew across the world after the revolutionary wars of liberation in China, Cuba and a number of other colonial and semi-colonial countries, the black civil rights movement in the US, the resistance to the Vietnam War and the new Palestinian resistance. The most important impression was made by the French May Revolution of 1968, which was followed by massive labour strikes throughout Europe. In Eastern Europe, too, the Stalinist regimes were shaken by the Czechoslovakian Prague Spring in 1968 and labour strikes in Poland in 1970 and 1976 demanding democratic freedoms, not capitalism.

Both internally within the social democratic left and externally, the debate at this time was heated about the path to socialism through reform or revolution, as well as against Maoism, which dominated the Vietnam movement and the new left’s sectarianism towards the labour movement.

The CWI was a child of 1968 at a time when much of the world seemed to be tilting towards some form of socialism.

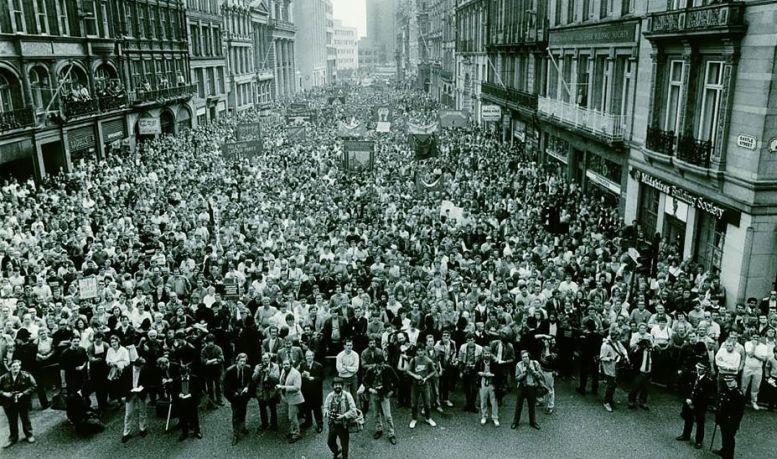

Just four days after the formation of the CWI, young officers also overthrew the military dictatorship that had ruled Portugal since 1926 and, three months later, the ten-year military junta in Greece also fell. In England, where the meeting was held, the right-wing Tory government had just fallen after an election, following a massive strike wave and a victorious miners’ strike in which it openly raised the question of which class should “run the country”.

At the same time, the murderous September 1973 coup in Chile against the left-wing government of Salvador Allende provided new and strong arguments for the need for revolutionary and internationally organised parties, which would dare to spearhead revolutionary solutions when capitalist sabotage would inevitably set in against any socialist challenge.

But it was through contacts with the British Militant group that both we and a lot of young socialists in other countries were able to find the Trotskyist classics and be broadly convinced that their interpretation of post-war developments and tactical orientation was more correct than that of other left groups, including those also calling themselves Trotskyists we had come into contact with, such as the French Trotskyist Pierre Frank.

The central conclusions were the realisation that without international perspectives, programmes and policies it is impossible to change society and that, as Marx and Engels already explained, it is the organised working class which, because of its role in production and thus the class struggle, can rally all the oppressed behind it, defeat capitalism and lead the way to a democratically planned, socialist democracy.

Read more in: Programme of the International (1970), by Ted Grant available at: www.marxists.org/archive/grant/1970/05/progint.htm

The nodes of the CWI’s red thread began with the theoretical contributions of Marx and Engels and the pioneering socialist period of the labour movement, before the outbreak of the First World War. This saw the majority of social democratic leaders reneging on their promises to oppose the war by all means by instead rallying behind the governments of their own countries. This led on to support for the Russian October Revolution that shook the world and marked the beginning of the end of the world war, as well as to the founding of the Communist International guided by Lenin and Trotsky during its first four congresses. This was the period before it degenerated, after the defeat of the German revolution and Lenin’s death, into a foreign policy tool of the bureaucratic counter-revolution in Russia. We then wanted to tie the thread to the Trotsky-led left opposition to Stalinism and the complete degeneration of the Third International, embodied in the attempt in the 1930s to form a new, fourth Marxist International.

The formation of the CWI also represented a statement of Ted Grant’s and Militant’s views on the main contentious issues that had divided the Trotskyists in the post-war period.

A new revolutionary upsurge also came after WW2 in Europe, but was diverted in a way that Trotsky had not anticipated. It was first necessary to realise how Hitler’s bestial attack on the Soviet Union meant that the war against Nazi Germany came to the top of the agenda, after which the Red Army’s spectacular victory both weakened the Western capitalist powers and strengthened Stalinism. This was firstly, by creating a series of new states in the countries occupied by the Red Army, modelled on Stalin’s Soviet Union, while at the same time Mao’s Red Peasant Army was about to defeat the Kuomintang in China.

The prestige of the Stalinists had also been enhanced by the fact that, after initially defending the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact between Stalin’s Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, they eventually did a political u-turn after Hitler’s attack on the Soviet Union and played a leading role in the Western resistance movements against the German occupation and Mussolini’s Italian fascists. But the influence of the victory over Hitler’s Germany was used after the war to divert and contain, in tacit agreement with the Western powers, the revolutionary wave in the West that Moscow, without troops on the ground, could not control as it did in Eastern Europe.

Ted Grant also realised much earlier than others that the shaken capitalists after the war would be forced to lean on social democracy and allow a series of social reforms that strengthened it. This was a kind of counter-revolution in bourgeois democratic forms, instead of relying on military dictatorships, repression and Bonapartist states, as other Trotskyists believed. This also paved the way for a new capitalist economic upswing, which became a dominant trend from 1950 until the early 1970s.

Other debates concerned the class nature of the new regimes in Eastern Europe. Capitalism was abolished, but instead of a genuine working class revolutionary overturn as in Russia in 1917, these were new deformed workers’ states. From the start they were under the rule of a bureaucratic dictatorship with bureaucratic top-down state-owned industries on the same model as in Russia. But these were not degenerated workers’ states as was the case in the USSR because they were never democratic. Nor were they state capitalist, as some so-called Trotskyist groups believed.

Earlier than most, while Mao was still talking about 50 years of capitalism, Ted Grant had also predicted that under the new global power relations, Mao’s regime would be forced to establish a proletarian Bonapartist and deformed regime of the same character as Moscow.

The CWI also adopted the definition of several regimes established in the South after colonial wars of liberation or coups d’état in the former colonial countries as proletarian Bonapartist, having nationalised their economies on the model of Moscow. In a new albeit deformed way, this confirmed Trotsky’s theory of permanent revolution, which here meant that national liberation in some poor countries with a weak domestic bourgeoisie could not hold out against economic neo-colonialism without nationalising and bureaucratically planning the economy. In a new situation where imperialism was weakened while the revolution in the developed countries was delayed, deformed workers’ states still existed as models for these countries’ revolutionary intellectuals and radical officers, in societies where the working class was numerically very small.

Therefore, as in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, political revolutions would be necessary in the future to establish workers’ democracies also in those countries where rural-based guerrilla movements such as in Cuba, Vietnam and many other cases in Asia and Africa. To succeed in poor countries these nascent workers’ states would require the support of the coming social revolution in the West or the political revolution in the East.

It was a question that other Trotskyists opportunistically denied or ducked. The American SWP (Socialist Workers Party), which had joined the USFI (United Secretariat of the Fourth International) in 1963, became even more than others an uncritical cheerleader for Cuba, and later for the Sandinista half-revolution in Nicaragua.

USFI leaders like the Belgian Ernest Mandel, the Italian Livio Maitan and the Frenchman Pierre Frank also had great illusions about Mao’s China and “cultural revolution”. They had compromised in 1965 with a more critical SWP in China’s case to call for an ‘anti-bureaucratic movement’ in China, while rejecting the call for a political revolution. The furthest along in Maoist illusions was Maitan, who actively contributed to the dissemination of Maoist literature and lost a large proportion of the USFI’s Italian youth to Maoism.

The uncritical applause for the leaders of the colonial revolutions went hand in hand with a glorification of guerrilla warfare that sharply departed from the Marxist view of the peasants’ role in the Russian Revolution. The CWI also recalled Trotsky’s warning to China’s revolutionaries when he declared in 1932 that: “It is one thing when the Communist party, firmly leaning upon the flower of the urban, proletariat, strives through the workers to lead the peasant war. It is an altogether different thing when a few thousand or even tens of thousands revolutionists assume the leadership of the peasant war [… ] without having serious support from the proletariat. Then the danger is high that the peasant army, when it takes the cities, may soon be turned against the struggle of the working class.”

The CWI was even more strident in its criticism of the guerrilla romanticism that, particularly in Latin America, led to urban guerrillaism by heroic small groups in armed struggle and attacks with bombs and guns. Thousands of young people were lost in the resulting impasse in Argentina, Uruguay and other Latin American countries, while even in Europe the USFI gave uncritical support to the armed struggle of Basque separatists and the Provisional IRA in Northern Ireland. While the CWI strongly denounced this kind of individual terrorism. Our comrades in Northern Ireland also gave their all in the struggle for labour unity between Protestant and Catholic workers and a common class struggle which, in a future socialist federation, could also resolve the national question with guarantees of security and self-determination for all communities.

Having myself visited Palestinian refugee camps and organizations before contact with Militant, I was in direct agreement with the British comrades’ view that instead of small guerrilla groups’ pin-pricks from outside, which only strengthened the Israeli state, we must advocate a mass struggle both inside Israel and in its occupied territories (along the lines of the first intifada that followed). This pointed to the necessity of joint struggle by Palestinians and Israelis in favour of a socialist two-state solution in an ever closer federation.

Other points crucial to our political orientation concerned the economic and political crisis perspectives of the developed capitalist countries, where we agreed with the British pioneers that by the 1970s the long post-war upswing of capitalism had come to an end, which would inevitably undermine reformism, lead to an escalation of class struggle and bring about a radicalisation of the workers. And, as before, they would first turn to their traditional trade unions and labour parties for solutions.

Since Trotsky’s day, most Trotskyist groups, purged from the Stalinized communist parties, had tried to find ways out of their isolation by going in and finding new radicalised layers in the other social democratic and workers’ parties or breakaways. This tactical approach was called entrism. During the long post-war upsurge, however, this often degenerated to the point where some of the Trotskyists hid their own programme and adapted to the reformist ideas of these parties with “deep entrism”.

It was a tactic that by the end of the 1960s had already been abandoned by most of those who called themselves Trotskyists in favour of an orientation to the colonial liberation struggle and the new radical currents among students and intellectuals.

Not so the Marxist tendency around the Militant in Britain. Without denying the importance of student and middle-class radicalisation, the formation of the CWI in 1974 meant a focus on getting in touch with the new radicalisation that had become apparent in the workplace, in the trade unions, among the rank and file of social democracy and, not least, in the youth wings of social democracy, as confirmed by rapidly growing support for our ideas.

It was an orientation everywhere possible that quickly led to contacts and new groups, eventually in 35 countries on all continents. Although we did not speak publicly about the CWI for a long time (this would be grounds for expulsion from social democracy), we were always maximally open about our theoretical foundations, economic and political perspectives, always starting with international perspectives and a shared international analysis and program.

The CWI, of course, like Trotsky in his day, also warned of a period of “revolution and counter-revolution” in which the crisis of humanity could be boiled down to a crisis of proletarian leadership. But we hoped that this would somehow be overcome in a race between the social revolution against capitalism in the West and the political revolution against Stalinism in the East. As after the First World War, we looked forward to new revolutionary mass parties sooner or later emerging from the break-up of large minorities or perhaps even majorities of the old social democratic parties and their youth organisations.

This orientation to the traditional labour parties was maintained by the CWI in those countries where they existed into the early 1990s, even from outside in countries such as Spain and Sweden where we were met very early on with expulsions to block our ability to win significant minorities.

In Greece, we orientated ourselves to the new socialist party Pasok, which we predicted would be formed before it even existed. In South Africa, the CWI orientated itself in a similar way as a Marxist tendency in the ANC; in Sri Lanka, we won over most of the active members of the former mass Trotskyist Lanka Sama Samaja Party. In countries like the US and Nigeria, we campaigned among trade unionists for a new labour party that had never existed in these countries.

The CWI was most successful in Britain where Militant, with its majority in the LPYS and, until the mid-1980s, a strong left reformist wing around Tony Benn, was so successful that a book by Michael Crick called our comrades the fifth strongest party in the country. Militant had three of Labour’s MPs, majority support in Liverpool, strong positions in several unions and at its peak,8,000 members.

Militant also led a series of epic campaigns, such as Liverpool City Council’s two rounds of battles against Thatcher’s cuts to local government funding, massive support for the great miners’ strike of the 1980s, and the victorious mass non-payment campaign against the attempt to introduce a Poll Tax that spelled the beginning of the end for Margaret Thatcher.

The objective conditions for this orientation changed with the historical collapse of the Stalinist states and the capitulation of social democracy everywhere to capitalism’s demands for neoliberal deregulation, and the destruction of welfare and progressive social reforms.

The Social Democrats and labour parties thus steadily lost most of their character as bourgeois reform parties with a mass base of workers who identified them as “their party”. Increasingly, they became no different fundamentally from other capitalist parties.

More and more people today realise that capitalism’s frightening wars, military arms race, environmental and climate threats are moving closer and closer to tipping points that can actually destroy all human civilisation. Nevertheless, the collapse of Stalinism together with the loss of both a reformist workers’ movement and significant revolutionary alternatives still means that confidence is lower than ever in modern times in both what a functioning socialist alternative to capitalism should look like and have the power to be implemented.

We can no longer, like Trotsky in the 1930s or the CWI in the past, reduce the crisis of humanity to a crisis of leadership for the labour movement. Today’s crisis extends further and encompasses the need for basic working class organisations to be rebuilt, created through struggles, and not only to struggle against bad leadership. This means the Marxists today face a two-fold task: to be the most energetic fighters to launch and help organize mass struggles, including broad initiatives and left electoral challenges where appropriate, while at the same time fighting within these mass struggles and initiatives for the most advanced layers to join us in building a revolutionary socialist alternative.

It is a difficult situation that has not only created several splits in the CWI but also weakened other parts of the socialist left everywhere. In 2019, CWI’s members and sections were confronted with a crisis when a minority around our former leadership chose to split away, having become politically disorientated and increasingly bureaucratic. This was when CWI changed its name to ISA (International Socialist Alternative). However, the more complicated the task has become, the more important it is to defend and build a global Marxist movement capable of using the dialectical materialism developed by Marx and Engels to constantly re-analyse what is happening in all parts of the world, not least in Asia and the South where the industrial working class is today most numerous.

It is still true that it is the working class, increasingly organised in the future, that must support a global democratic socialism, now more than ever with a key role for the many women in schools, health care and other sectors. This is posed in a more threatening race against time as capitalism and imperialism threaten the planet’s survival. At the same time, protest movements against war and environmental degradation, dictatorships and authoritarian regimes, racism and oppression of various forms are taking place everywhere, all of which must eventually be captured and channeled by a historically conscious world socialist party at the head of a worker-led mass movement of movements.