Andy Ford is a member of Socialist Alternative (England, Wales & Scotland).

2020 marks 70 years since the untimely death of George Orwell (Eric Arthur Blair) from tuberculosis in University College Hospital, London. His political and literary legacy has been fought over ever since.

Early years

Orwell was born in 1903 in Motihari, India, as his father was in the Indian Civil Service. After his mother moved him back to England he did not see his father again until 1912 and he later wrote that he could hardly remember him except as a person “who was always saying no.” He was placed in a Sussex boarding school, St Cyprian’s, later recalled by him in the essay Such, Such Were the Joys. According to Orwell the school shared many features of his final dystopia 1984 with constant surveillance, arbitrary punishment and a fierce repression of sexuality. Orwell recalls the feeling that his every move was watched by the headmaster, a terrifying figure who dominated the school.

His parents were genteel but poor so Orwell was there on a scholarship and was pushed without mercy to get the grades to get into Eton, with the threat of ending up as “an office boy on £40 a year” as the grim alternative.

This continual effort to avoid sinking in the social scale underpins much of Orwell’s outlook. The Blairs were well-off in relation to working people, and were even distantly related to the Earl of Westmoreland, but they struggled constantly to “keep up appearances.” Orwell described this struggle perfectly in Keep the Aspidistra Flying. In his intermediate class position he was intensely class conscious with an abhorrence of the bourgeoisie but was never able to really adopt a working-class point of view, despite his sympathy for their struggles. It also meant that whenever things got really tough Orwell was usually able to tap into contacts to borrow money, find him a job or lend him a house.

Burma

Orwell made it to Eton where he was “interested and happy” but when he left in 1921 the family could not afford to send him to university and instead opted for the British Imperial Police. He was posted to Burma and his experiences there developed in him a lifelong hatred of imperialism. He noted that the British were in Burma for the teak and minerals but had to hypocritically pretend they were there to spread “civilisation” and Christianity. The racism, snobbery and hypocrisy he found in the British colonial service were the source material for his novel Burmese Days as well as one his first published works A Hanging, describing the inhumanity of capital punishment, (“Better to hang some fellow than no fellow…”), and the famous essay Shooting an Elephant. His feelings on his fellow servants of Empire were very clear:

“Year after year you sit in Kipling-haunted little Clubs, whisky to right of you, Pink’un to left of you, listening and eagerly agreeing while Colonel Bodger develops his theory that these bloody Nationalists should be boiled in oil. You hear your Oriental friends called ‘greasy little babus’, and you admit, dutifully, that they are greasy little babus. You see louts fresh from school kicking grey-haired servants. The time comes when you burn with hatred of your own countrymen, when you long for a native rising to drown their Empire in blood.”

Back to England

In England on leave, he wisely decided that keeping Burma British (to paraphrase Monty Python) was not for him and he returned to his family, now resident in Southwold, Suffolk. A friend advised him to “write about what you know,” and perhaps realising that life in a lower middle class family in a country town would not interest many people he began to seek out new experiences – venturing into the East End, staying in doss houses and occasionally living as a tramp. He used these experiences in Down and Out in Paris and London but it may be that the artificiality of the experience fed through into the book which does feel somewhat forced. For instance throughout his stay in Paris he was always able to borrow small sums of money when needed from his aunt, Nellie Limouzin.

In 1929 he returned to Southwold and used the family home as a base for his writing, supporting himself with tutoring and later moving to teaching in (very) minor public schools and crammers. Down and Out in Paris and London was published in 1933 and was reasonably successful, but Burmese Days was turned down around the same time.

London, the ILP, and the Clergyman’s Daughter

He began work on a novel based on life in Southwold, A Clergyman’s Daughter, which he continued to develop after moving to Hampstead where a relative had found him a job in a bookshop. The hours were not arduous which allowed him time to work on Burmese Days and Clergyman’s Daughter and he begin to enter the literary and political life of the capital. It was here that he first came in contact with the Independent Labour Party (ILP) which was to greatly mould Orwell’s political future. The ILP was primarily based on an ethical socialism but also had a group of Trotskyists working within the party which seems to have inoculated Orwell against the Stalinism which infected so many left intellectuals in the later 1930s and 40s. His experiences of the alienation of urban living, life in lodgings and of genteel poverty informed his 1936 novel Keep the Aspidistra Flying which most people, and Orwell himself, regarded as something of a failure, although Gordon Comstock’s rebellion against the system and eventual defeat prefigures that of Winston Smith in 1984.

A Clergyman’s Daughter was published in March 1935. Strangely, given Orwell’s later use of the plot of We by the Soviet writer Yevgeny Zamyatin for the outline of 1984, its story of a young woman tyrannised by the rules of her home and small town mores is strikingly similar to Zamyatin’s short story The Precepts of Compulsory Salvation – although there is no evidence of Orwell reading Zamyatin’s work at that time. The novel is a brave but unsuccessful experiment as it combines a realistic depiction of small town life, a more or less journalistic account of hop-picking in Kent, and surrealistic passages in London thought to be influenced by James Joyce.

The Road to Wigan Pier

Burmese Days was eventually published the same year, in July, and received a favourable review from his old school friend Cyril Connolly which opened the way for a commission in 1936 from Victor Gollancz to visit the north of England to report on conditions there.

He spent most of his time in Wigan investigating the lives of the miners which included a trip down Bryn colliery and visits to unemployed miners in their homes. He then rented a cottage in rural Hertfordshire to write up his notes. The book has an odd structure with the first half being a description of coal mining and the wages, diet and lives of the miners, with the second half being a general socialist manifesto combined with a critical review of the socialist intellectuals of the time. Again Orwell does not quite succeed in overcoming his own class prejudices and one working-class Wigan journalist wrote that Orwell had failed to pick up on “the worker’s enormous zest for life, the richness of his humour, and the simple philosophy which sustains him so long in adversity.”

Catalonia — Orwell meets the revolution

Just as he was finishing Road to Wigan Pier Franco launched his counter-revolution in Spain and Orwell was immediately drawn to the armed struggle against fascism. Using his ILP contacts he enrolled in a militia linked to the POUM political party which had been influenced by Trotskyism at times. This had a huge effect on his experience of the Spanish civil war as at first hand he saw the Stalinists first blocked the workers’ struggle, and then attacked and strangled the working class movement in Catalonia, followed by a monumental campaign of lies, frame-up and murder. All this bore fruit in his marvellous account of events in Barcelona, Homage to Catalonia. The book begins with Orwell describing the sheer exhilaration of seeing a city under working class control:

“It was the first time that I had ever been in a town where the working class was in the saddle … every wall was scrawled with the hammer and sickle and every shop and café had an inscription saying that it had been collectivised.”

But when he returned to Barcelona after 3 months in combat he could see for himself how the Stalinists had quietened the previous revolutionary fervour and was further dismayed to find that they had kept back modern rifles to use in police action against the Anarchists and Trotskyists while leaving the troops actually fighting the fascists with antiquated rusty rifles. He helped the POUM in the Barcelona May Days where the Stalinists disarmed their political opponents and then set about hunting them down. Luckily for him he went back to the front the day before the POUM was declared illegal.

On returning to the lines he was shot through the throat and was lucky to survive; after treatment he was even luckier to avoid arrest by the Stalinists. With some difficulty he returned to England and began work on what became Homage to Catalonia which was published in April 1938, only to sell barely 600 copies.

Nevertheless Homage to Catalonia is a tremendous book. Its strength is its truthfulness: firstly as to Orwell’s inspiration at seeing workers in control, and then in describing Stalinist treachery at a time when most of the left accepted monstrosities like the Moscow Trials and suppression of the POUM as necessary acts. It marked a high point in Orwell’s political outlook and it left an enduring mark on him. In a 1937 letter he wrote “At last I really believe in Socialism which I never did before,” and near the end of his life he said “Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic Socialism, as I understand it.”

Even the word “homage” indicates his purpose in writing the book — to honour and remember the working class of Catalonia who had fought fascism with so much courage, only to be betrayed. He felt almost alone in doing it, but did it nonetheless.

Coming Up For Air

Once back in England Orwell suffered health problems connected with his wound or possibly the beginning of the tuberculosis which was to kill him. A novelist friend paid for Orwell and his new wife, Eileen O’Shaughnessy, to go to Morocco over the winter of 1938–39 and it was here that he wrote the novel Coming Up For Air. Orwell succeeded here in writing a successful novel, maybe for the first time. It concerns the inner thoughts of George Bowling, a grown-up version of the “office boy on £40 a year” that Orwell could have become, who is deeply dissatisfied with his work, his children, his marriage and the modern world in general. Bowling decides to return the scenes of what he remembers as an idyllic childhood before WW1, only to find it has been built over into an ugly suburb and the pond where he used to fish is now filled with rubbish. Coming Up For Air describes the impossibility of a return to the past and takes a jaundiced view of the fate of the middle classes, enslaved by their mortgages in an ugly drab existence. Our anti-hero’s visit to a Communist Party meeting is clearly the model for the Two Minutes Hate of 1984 and he is plagued throughout by premonitions of war.

Orwell in war time

As George Bowling had predicted the war came, just weeks after the book’s publication. Orwell and his wife got jobs in the censorship department of the Ministry of Information, experiences transmuted by Orwell into Winston Smith’s labours in the Ministry of Truth. He wrote many essays at this time, published as Inside the Whale and The Lion and the Unicorn in which he evolved a vision of “English socialism.” Despite the term it is not as reactionary as it sounds. He believed that the class system was hampering the war against the Nazis which could only be prosecuted effectively by a socialist government. In this he was not so far from Trotsky’s controversial “Proletarian Military Policy” as Orwell, for instance, believed that the Home Guard had elements of a people’s or workers militia.

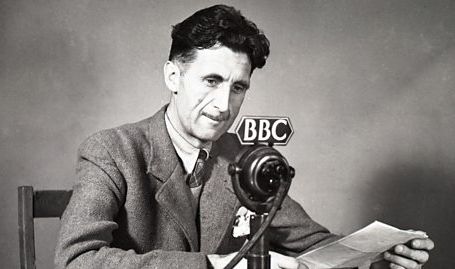

He also began writing for Nye Bevan’s Tribune paper and the BBC. His 1943 adaptation of the fairy tale The Emperor’s New Clothes was clearly an influence on Animal Farm which was sub-titled as A Fairy Story. After the comparative failure of Homage to Catalonia, Orwell had decided that people would better understand politics through fiction.

Animal Farm was published eventually, after efforts at censorship by the British Stalinists, in 1945. No wonder they wanted to block it – the book is an excoriating attack on the regime and crimes of Joseph Stalin in the form of an extended allegory. Each of the main protagonists of the Russian Revolution has its place in Animal Farm’s farmyard – Lenin, Stalin, Trotsky, the heroic Soviet workers, the GPU, and even the Russian Orthodox Church is shown as a cowardly raven. The book ends with the Soviet bureaucracy, represented as pigs, living well off the working class and hob-nobbing with the human farmers on an equal basis in a thinly disguised depiction of the Yalta conference of 1945.

Despite its later promotion by the CIA, Animal Farm defends at all times the animals’ initial revolution against intolerable conditions, and the true hero is Boxer the hard-working cart horse who symbolises the Russian working class. After rebuilding the farm twice Boxer is taken off to the knacker’s yard by the pigs — just like the millions of Russian workers shot or sent off to gulags after rebuilding the USSR twice; once after the civil war, then again during the 5 year plans.

1984

While Orwell was trying to get Animal Farm published he picked up work as a war correspondent for the Observer and covered the liberation of Paris and the occupation of Cologne. While he was abroad his wife died unexpectedly from the complications of an operation leaving him with custody of his adopted son, Richard.

It may be that this personal tragedy, as well as the bleak political and economic outlook in the aftermath of the war, informed the desolate vision he created for 1984. It is easy to forget that in 1946 no-one knew that there would be a world boom of capitalism and the consumer society. All Orwell could see was that millions of working class people had died in the war, the destruction of cities, thousands of refugees and concentration camps, economic dislocation, and the resurgence of Stalin’s repellent regime which now extended into the heart of Europe. Even in the “western democracies” self-censorship was the rule with most writers either fellow travellers of the Communist Party or jingoistic supporters of Churchill and the Empire. No wonder the original title for 1984 was The Last Man in Europe. Also Orwell was writing the book in a freezing cottage on the Scottish island of Jura, 9 miles down a track from the end of the only road on the island.

Orwell felt that only he and a tiny number of collaborators still stood for objective truth and real socialism. Because he had not found his way to the small forces of Trotskyism, despite a number of near misses, he could not develop an understanding of the period he was living through. The central motifs of 1984 are ugly – institutionalised lying, torture refined to perfection, and a boot stamping on a human face forever. But there is also hope – the thrush singing in freedom in the countryside just because it can, just like Orwell telling the truth in a brutal and degraded world; Winston Smith’s awakening to love for Julia, and above all the working class.

A repeated refrain in the book is “if there was hope it lay in the proles.” They alone retain a freedom from the Party and have to be kept down by a mixture of repression and mass distraction. In this he was of course correct: only the working class can overthrow dictatorship and class oppression and this is precisely why our masters spend so much time and effort preventing working-class people from understanding their situation; and understanding their power.

1984 was published after heroic efforts by Orwell, writing through his terminal tuberculosis, in 1949. He died in London on 21st January 1950.