Five weeks and $610 million dollars later, we have ended up more or less right back where we started. While some seats may yet flip as mail in ballots are counted, at time of writing no party has gained or lost more than two seats compared to before parliament was dissolved. Canada has another minority Liberal government, with all the major parties having virtually the same number of seats and share of the votes as before.

Only on the fringe, with the rise of the far-right People’s Party and the collapse of the Green Party vote, was there any notable change. Canadians were uninspired by the parties contesting the elections, with a historically low turnout of only 58.7 percent after 99 percent of polls reported.

Immediately as the election was called, the Liberals lead in the polls began to collapse in favour of the Conservatives under Erin O’Toole. No doubt the Liberal’s collapse can be explained in large part by the consensus that this was an unnecessary and cynical election call, although the gap in the polls got tighter towards the end of the campaign. To date, the Liberals have received 32.6 percent of the votes cast to the Conservatives 33.7 percent, with the NDP coming in at only 17.8 percent. Because of the distortions of the first-past-the-post system, the Liberals won 159 seats, ahead of 119 for the Conservatives, and the Bloc at 33 and NDP at 25, essentially the same as in 2019.

What can we learn?

Elections do give an indication of wider moods and trends. Probably the most important trend was that all major parties were proposing major increases in spending. Even the Tories talked of $50 billion in extra spending. This would have been unthinkable in 2015, an election in which many credit the Liberals’ victory to being the only party to run on a modest budget deficit. Gone, at least for now, is this neoliberal orthodoxy of cutting taxes and spending to balance the budget.

There was considerable talk about the housing crisis during the campaign, something that has not been such a focus in previous elections. The big three parties all promised to create more housing and proposed various measures to make it easier to buy a home, but none got the root causes of the housing crisis, which is the commodification of housing and for-profit development. The NDP did say some things about creating “affordable” housing, and about how to discourage investors who use housing to make a profit and drive up prices, but they failed to directly oppose private ownership and development of housing and to call for publicly owned social housing.

In an interesting shift for the Conservative Party, leader Erin O’Toole cultivated an image of a someone who cares about working Canadians, a contrast with his predecessors, Scheer and Harper, who preferred to talk about “families” and “the middle class.” Of course, O’Toole is just a wolf in sheep’s clothing. One of the ways they said they were helping workers was to propose a system to provide partial EI benefits to gig workers. But this policy was written by Dan Marder, a former lobbyist for Uber, with the intention to entrench gig workers’ status as “independent contractors” rather than employees.

These pro-worker overtures were part of a general shift of the Tory party towards the centre, something that is not without controversy in the party ranks and may have caused some voters on the right to switch to the People’s Party. Just as we are hearing similar rumblings about Jason Kenney in the United Conservative Party of Alberta, we could see a move against O’Toole’s leadership in the coming days, as part of a strategy to pull the party back to the right.

Rise of the People’s Party

The rise of the far right and reactionary People’s Party of Canada, under leader and founder Maxime Bernier, should serve as a warning. The PPC got more than twice as many votes as they did 2019, from around 300,000 to over 840,000. Many PPC supporters are anti-maskers and anti-vaxers who believe that vaccine mandates are an unjust infringement on personal freedom, and/or part of a creeping authoritarian conspiracy.

Bernier has often been described as a libertarian, and the PPC platform included “ending corporate welfare” in addition to opposing immigration and multiculturalism. There is a layer of aggrieved middle-class voters who correctly see their enemies as the billionaires and powerful corporations that get rich while the rest are struggling, but from this justifiable anger they draw reactionary conclusions. The rise of the PPC could be the sign of a growing polarization in society, with the growth of right-wing populism and neo-fascist trends like those behind the January 6th attack on the US capitol.

Green Collapse

After a historic surge forward for the Green Party in 2019, in which they won over a million votes and three seats, their support collapsed during this election. Elizabeth May resigned as leader after the last election, and the 2020 leadership race was a tumultuous one in which a left-wing “eco-socialist” movement, including leading candidates Dimitri Lascaris and Meryam Haddad, were blocked by the old guard. Despite earlier assurances from May that she would remain neutral in the campaign, when it became clear that Lascaris could win she put her weight behind the centrist Annamie Paul, who ended up winning narrowly. It turns out that Paul’s politics, more conservative than most Greens, became a major liability as she has clashed with others in her party over supporting Zionism and the Bolivian coup against Evo Morales. There were even calls from within the party for a non-confidence vote in the lead up to the election.

One could almost feel sorry for Elizabeth May, now back to just 2.3 percent of the votes and only two MPs, including Mike Morrice in Kitchener, whose win was likely a fluke as the Liberal candidate stepped down mid-campaign. However, May helped make this mess by going back on her promise to remain neutral during the leadership. Paul, herself, almost exclusively campaigned in her riding Toronto Centre, which was a long shot. She came in fourth. Undoubtedly, we will see these internal conflicts boil over now that the election is over.

Québec

The election in Québec was a race between the Liberals and the Bloc Québecois, with the Conservatives and NDP in a distant third and fourth place, respectively. When the campaign started the Liberals had a strong lead in the polls, but this changed after a decisive moment in the English debate.

During the debate, a journalist asked a pointed question to the Bloc Leader Yves-François Blanchet about Bill 21 of the Québec legislature (the National Assembly). The bill prevents public service workers like teachers, judges and police officers from donning religious symbols on the job. While the bill is clearly discriminatory against religious minorities, polls show it is popular among Quebecers and it is defended by the BQ as a way to reinforce Québec’s “secular values.” When politicians or journalists are seen to be interfering in the sovereignty of the Québec nation, it can bolster support for nationalist parties like the Bloc.

The other party leaders were asked about Bill 21 during the campaign. O’Toole said that he would never attempt to challenge a law passed by a provincial legislature. Trudeau preferred to sit on the fence saying that he “disagrees” with the law but won’t call it “discriminatory.” Singh took an only slightly more firm position saying that the bill was discriminatory, but that he would not commit to challenging it if the NDP formed government.

Winners and losers

There were a few notable results in some individual ridings as well as in Alberta. Jenica Atwin, who was elected as a Green MP in Fredericton before switching to the Liberal party after a conflict over the Zionism of the party leadership, narrowly won her seat as a Liberal. Three ministers: Bernadette Jordan, Maryam Monsef, and Deb Schulte, lost their seats to Conservatives. The Conservative Party vote in Alberta, a traditional Tory stronghold, was down 14 percent and the NDP vote increased more than any other party. The NDP was able to pick up one new seat, as Blake Desjarlais beat the incumbent in Edmonton. While the Liberals were previously shut out in Alberta, they picked up two new seats: George Chahal in Calgary and Randy Boissonault in Edmonton.

But on the whole, very few seats changed hands. This election must be considered a failure for all parties except perhaps the People’s Party. For the Liberals, it is clearly a failure to have not only not won a majority, but to have increased their seats by just two. The Conservatives and the NDP, for their part, have failed to take advantage of the Liberals’ tactical blunder.

The need and opportunity for a real left party

The fact is that the parties contesting this election did not really present a wide range of choice. While there are some rhetorical differences of course, when you drill down to the details, there is a lot of agreement and overlap between the Liberals and the Conservatives. The People’s Party represents a somewhat more reactionary option, still small but growing and buoyed by the dissatisfaction with the traditional parties. The NDP is to the left of the Liberals and Tories, but they remain a purely electoral machine without vibrant internal democratic structures or a willingness to engage in working-class struggle and campaigns on a day-to-day basis. Only the PPC seems to be able to capture real energy and emotion in the public, albeit by amplifying right-wing reactions.

The NDP have squandered a golden opportunity. What better time than after a bungled pandemic response, economic crisis, and thoroughly damning IPCC report could there be to promote a bold alternative vision for society that would motivate the youth and progressive working class? We expressed tepid support for the NDP’s mildly more left-wing program this election, but ultimately the party’s refusal to break with the fundamentals of contemporary capitalist society meant that they were unable to connect with the mass of workers and youth, who have already concluded that this society has no future.

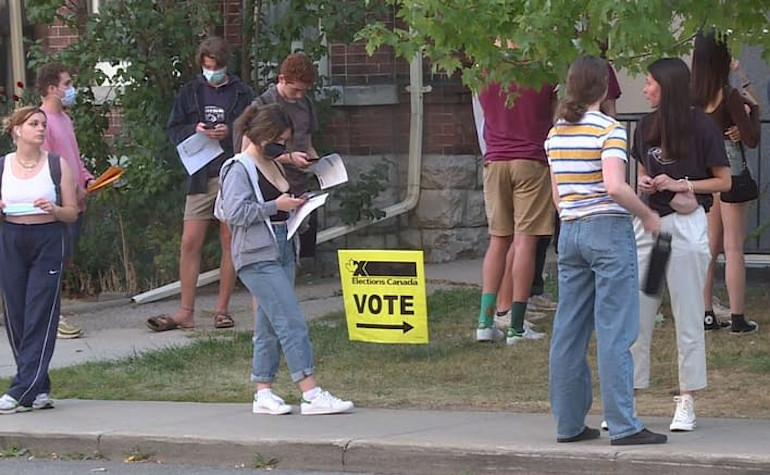

Historically, youth don’t participate in electoral politics because they don’t see it as being relevant to their day-to-day lives. But that’s not to say that youth aren’t politically engaged. Indeed, today youth are more radicalized than they have been in decades, with hundreds of thousands of Canadian youth participating in Climate Strikes in 2019. Mass protests have ebbed due to the pandemic but have been re-emerging in fits and starts with the 2020 Black Lives Matter solidarity movements, protests against the Trans Mountain Pipeline, and in solidarity with Wet’suwet’en and Mi’kmaq Indigenous struggles.

The issue is that the scale of the problems facing youth today, including not just climate change but the fact that capitalism has been in a state of economic crisis for their whole lives, are completely out of step with the policies and proposals being debated in this federal election. Youth are increasingly losing faith in parliamentary democracy and are turning towards independent organizing and participation in mass movements as a way to demand change.

The fact that this election has resulted in no change at all will reinforce the feelings of many that parliamentary democracy is incapable of addressing the problems we face today. But it may also reinforce conclusions that political organization of any kind is useless, and this kind of anti-organizational or doomerist conclusion is something that genuine socialists must argue against. The working class will need to learn through experience that political organization on an independent class basis is the most useful tool it has. A mass, campaigning party of the working class that is ready to directly confront the rule of big business and the rich with a socialist program will be capable of winning victories both inside and outside parliament.