Serge Jordan is a member of the Committee for a Workers’ International.

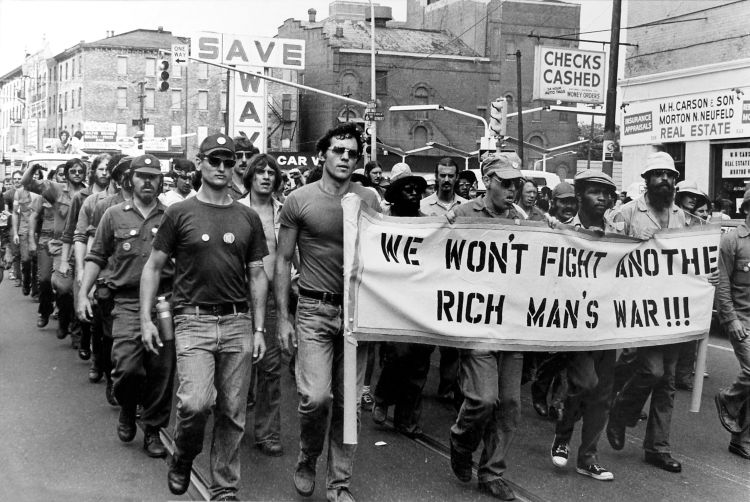

By rising up onto their feet, the masses in Sri Lanka have awakened the imagination and courage of millions of workers and poor fighting against the effects of the capitalist crisis in South Asia and internationally.

The spectacular storming of Colombo’s Presidential residence on Saturday July 9 marked a qualitative sharpening of the contest between revolution and counter-revolution in Sri Lanka. This mass insurrectionary explosion sealed the political fate of the once-powerful autocrat Gotabaya Rajapaksa and of his corrupt dynasty.

Forced out of his palace by an entire country in uproar, the disgraced President spent the following days hiding out and organizing his escape from the island. For many Tamils, there is a certain irony at the sight of Rajapaksa being forced to flee his home in fear and of his Prime Minister’s house being burnt down —an experience so many of them had to endure in the past under the watch of these murderous-gangster politicians.

Gotabaya initially tried to fly to Dubai via a commercial flight from Colombo’s international airport but was blocked in his tracks because airport staff and immigration officers prevented him from leaving the country. This is one of many examples attesting to the awakening of the long-untapped power of the Sri Lankan working class in the course of the “Anatha Aragalaya” (‘Peoples’ Struggle’).

With the help of the military, “Gota” finally managed to escape in the early hours of Wednesday morning on board a military jet that landed in the Maldives Islands. No sooner did he land in the Maldives that protests broke out against him over there, mostly by Sri Lankans who live in Male, Maldives’ capital, demanding the local government not to shelter this criminal.

He then boarded a plane to Singapore on Thursday. Singapore’s government, which boasts of its culture of “zero tolerance” against corruption, has visibly no qualms about harboring the infamously corrupt Gotabaya Rajapaksa on his way to exile. From Singapore, he finally handed over his official resignation letter, having waited to be in safe havens before enacting it and giving up on his presidential immunity —which he had kept until then so as to shield himself from prosecution.

Pressure cooker

In Sri Lanka itself, the boiling rage of the masses has not cooled off, and stands ready to re-explode. Ranil Wickremesinghe, the latest prime minister who initially announced that he would step down last Saturday, was appointed by an on-the-run Rajapaksa as the acting President.

This manoeuvre, since then officially ratified by the Chief Justice, enraged the streets, who rightly see Wickremesinghe as a proxy for the Rajapaksas to pull the strings from behind the scenes. Even when formally a political rival, Wickremesinghe had saved the Rajapaksa family from prosecution when they were out of power between 2015 and 2019. The last two months have seen him playing a similar role, while at the same time, implementing further austerity and preparing an interim budget whose central objective was admittedly to “cut expenditures to the bones.”

His nomination triggered renewed demonstrations across Colombo since last Wednesday; on that day masses of people tried to enter Parliament, and stormed and captured his office. Violent clashes with the security forces ensued that led to a young protester succumbing to his injuries after being tear-gassed by the police.

Divisions

The July 9 uprising has laid divisions in the political establishment and the state apparatus wide-open. Opposition parties first contested the “constitutional legality” of having Wickremesinghe as interim President. Fractures have since then also emerged within Rajapaksa’s party the Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP) between a wing lining up behind Wickremesinghe, and another contesting him and his ambition to become full-time President.

One of Wickremesinghe’s first decisions was to appoint a committee of military and police commanders to whom he gave the green light to do “whatever is necessary to restore order,” calling the protesters a “fascist threat to democracy.” But last Thursday the Sri Lankan Army was reported to have declined instructions by Wickremesinghe to use force against the protestors. This seems to confirm the discord prevailing at the top about who should be in charge, and the concerns among sections of the ruling class that applying full-blown repression against the movement at this stage could backfire.

Symptomatic of the political volatility enhanced by the revolutionary toppling of the regime’s head was last week’s public statement by the country’s former army chief, Fonseka. He issued a call to the military asking them not to follow the unconstitutional orders from the acting president and to instead “raise their weapons against corrupt politicians.” Fonseka served as Sri Lanka’s army commander during the final years of the war and is one of the architects of the genocide against the Tamil people. His positioning is an attempt to tap into the growing turmoil affecting the army in order to channel the current movement down a path that would keep his lot untarnished by the revolutionary wave. The Aragalaya should appeal to the lower ranks of the army to raise their weapons not only against corrupt politicians, but also against all military officers responsible for war crimes— and Fonseka features high on that list.

Opportunities and dangers

Last week’s stormy events in Sri Lanka have unleashed enormous revolutionary potential and inspired millions worldwide by showing the power of mass movements. Saturday’s historic moment led to elements of “dual power:” beyond the official power of the state, the real power had moved onto the streets, and nerve centers of state power — the Presidential residence building, the President’s office and the official residence of the Prime Minister — were occupied by the masses, who refused to budge until they were sure that the President and the Prime Minister resign for good. These sumptuous buildings were even reconverted into open museums, with community kitchens serving free food, a makeshift public library and other amenities. Last Wednesday, protesters also managed to break into the state-run TV station, once a mouthpiece of the Rajapaksa regime, and for a while, to take control of the broadcasting program.

However, despite having the upper hand after snatching their most significant victory yet, the protest movement does not have a fully identifiable and authorized leadership, nor a cohesive political program as regards what should come next. Last Thursday afternoon, all the occupied buildings bar the Presidential secretariat were handed over back to the state. The storming and occupation of the Presidential residence and other state buildings had yet immense support across the island and beyond. They could have been defended through a clear public appeal to the country’s working class, its organizations and the revolutionary masses at large, and used as a launchpad to further rally and organize the struggle — including, for example, to convene the “People’s Council” protesters have demanded in their “Action Plan for the Future of Struggle” published on July 5. Instead, the state will now use the recapture of these buildings to regroup and go back onto the offensive, as part of its multi-sided attempt to restore the bruised credit of its institutions.

In the meantime, the frantic manoeuvres of the political establishment to try and put together a so-called “all-party” government are going unabated. These are nothing but an attempt to bypass the will of the revolutionary masses by stitching a government above their heads — along with the rotting remnants of the SLPP, which still formally commands a majority in the parliament.

Any all-party government (provided it even sees the light of day) will be at the mercy of a party full of loyalists and ex-loyalists of Rajapaksa. Besides, none of the parliamentary parties, opposition and SLPP alike, challenges the constantly-hammered idea that there is no alternative to resuming bailout talks with the IMF, and to swallowing the brutal neoliberal economic plans attached to those. Most of these parties, echoed by Western embassies, the UN, the big business elite and the religious establishment, also continue to swear by the current Constitution, that enshrines the system of executive presidency which gives dictatorial powers to the President and the sectarian, Sinhalese-Buddhist character of the state.

President “elections”

The Parliament voted on July 20 to confirm Wickremesinghe as new full-time President. Neither he nor any of the other candidates represents the aspirations of the millions who have made this vacancy of the presidential seat possible in the first place. All also happen to be, to varying measures, fierce opponents of the Tamils’ right to self-determination.

As well as the successful Wickremesinghe, the other candidates were the above-mentioned Fonseka, SLPP member Dullas Alahapperuma —another Sinhalese-Buddhist nationalist and formerly staunch ally of Rajapaksa, Sajith Premadasa — leader of the right-wing Samagi Jana Balawegaya (SJB), the largest opposition party in Parliament, who preaches “extreme austerity,” and Anura Kumara Dissanayake, leader of the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP).

The JVP is the only one of these parties that has some influence among sections of the Aragalaya; however, it has a long track record of pandering to Sinhalese chauvinism, argues to approach the IMF “with caution,” and its very participation in this Presidential election masquerade reflects its steep integration into the ruling class’s anti-democratic manoeuvres aimed at reviving the decaying and despised institutions of the old regime. Some of the most popular demands in the movement include “225 Go Home” — a reference to the 225 members of Parliament — and the abolition of the executive presidency, the very post all the candidates ran for.

The new President was chosen by the political forces and institutions who base their legitimacy on the old system and he will go against the demand for “complete system change” raised by the movement, and should be rejected outright. The same clique of pro-corporate politicians who are trying to usurp the victory of the masses are desperate to push them off the streets. This is the real reason behind Wickremesinghe imposing since Sunday an island wide State of Emergency, justified by the need to “maintain supplies and services essential to the life of the community” —quite an irony coming from a man who has overseen such an economic breakdown that over a dozen people have died in miles-long queues for petrol under his watch.

What program?

This is a revolutionary struggle that requires revolutionary means. The only legitimate government is one originating from the living forces of the Aragalaya uprising itself. The movement could campaign for an island-wide revolutionary constituent “People’s Council,” convened via delegates elected locally from within the revolutionary movement, and with fair representation from all religious and ethnic minorities. Local committees of the Aragalaya, democratically elected and controlled by assemblies held in all neighbourhoods, villages and workplaces, would give a concrete shape to this idea, and allow the working class, the youth and the rural poor to fully control their own struggle and assert and develop their own basis of power.

As far as the economy goes, the mass movement should fight to impose an emergency relief program to address the catastrophic situation inflicted on the majority. Measures such as a workers’ control on travel and on capital flows need to be implemented to prevent other regime cronies and Rajapaksa relatives from leaving the country with their wealth, and the corrupt millionaires and billionaires from stashing their money abroad. The Rajapaksas’ riches need to be seized and used to provide immediate assistance to the poor and the hungry, and the huge defense budget be cut to reallocate spending for urgent social expenses. Neighbourhood committees could help impose measures of price control and organize the supply of vital goods like food and medicine to those in need.

The repayment of the debt is bleeding the country dry; the movement should argue for its immediate and unconditional repudiation, and reject any negotiations with the rapacious IMF. Instead of destroying what is left of public ownership in Sri Lanka (such as health and education) and open the country to wider privatizations, as this imperialist institution would like, the movement should demand public ownership over all the commanding sectors and resources and their planning according to needs, under the democratic control of workers and poor farmers, via a government of their own making.

Of course, such socialist measures will never come from the top, since all wings of the establishment are conspiring to continue with more of the same bankrupt capitalist economic policies, robbing the poor to fill the pockets of the already super rich. Measures like this would need to be fought for by decisive working-class action, marching on the footsteps of the hugely successful general strikes of April and May. Several trade unions have warned of countrywide strike actions if Wickremesinghe takes over as full-time president. Workers in all unions and workplaces should take their leaders at their word — as this is not the first time the leaders threaten something they then do not act on.

The new President will reinforce the apprehensions and fears from the Tamil and Muslim minorities about where the post-Rajapaksa political situation is heading to. It is absolutely crucial in these conditions that conscious efforts are made to extend a hand to these communities and to incorporate their just demands into the movement. The Aragalaya should fight for the end of the state-sanctioned oppression on the basis of religion and ethnicity, the extradition and popular trial of Rajapaksa for war crimes, the release of all political prisoners, independent investigations into the mass disappearances, the scraping of the draconian ‘Prevention of Terrorism Act’, the end of the military occupation and land-grabbing in the Tamil provinces, and the right for the Tamil people to freely and democratically decide their own future away from any state coercion.

By rising up onto their feet, the masses in Sri Lanka have awakened the imagination and courage of millions of workers and poor fighting against the effects of the capitalist crisis in South Asia and internationally. By embracing a socialist perspective as outlined above, they could hasten the demise of this system and usher in a new era of genuine international cooperation and social progress for all.