Originally published in February 2003 in Socialism Today.

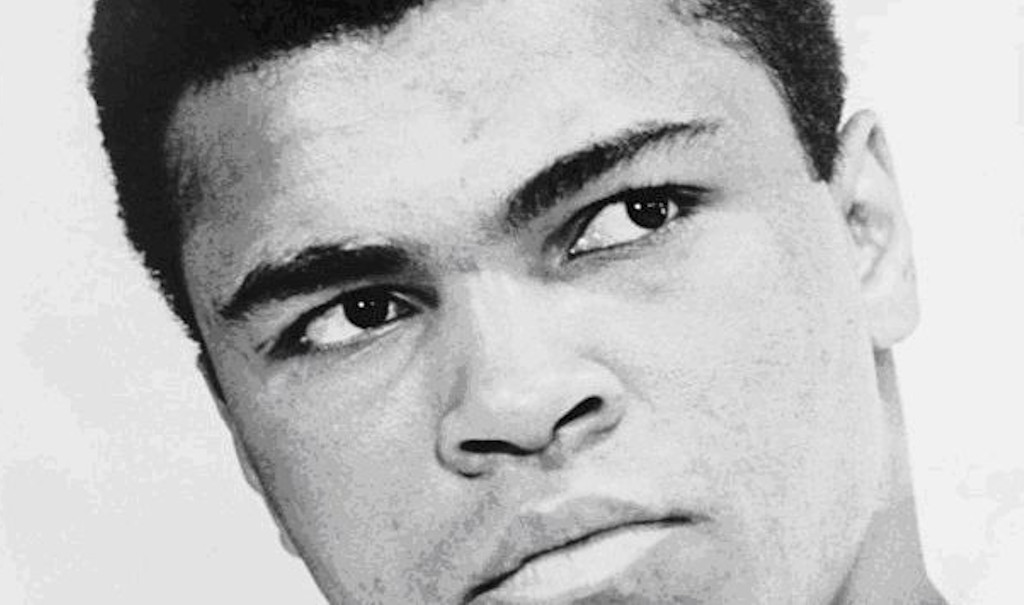

The great Muhammad Ali unfortunately passed away on June 3, 2016. He was admired not only as a world champion boxer, but as a fearless fighter against racism. His willingness to risk his career, prestige, and wealth to take a stand against racism and the Vietnam War inspired African Americans and oppressed people all around the world. As the Black Lives Matter movement has renewed the struggle against racism today, many people are looking back at the history of black struggles in search of the best ideas for how African Americans can win their freedom. This Marxist analysis of Muhammad Ali and the history of African Americans struggles is an important contribution to the discussion on the most effective strategy for black liberation.

DESPITE ITS CLAIM to be the ‘Land of the Free’, the U.S. ruling class has subjected blacks to systematic racism since the beginnings of colonialism. Blacks, however, have fought tenaciously to end the denial of even the most basic rights, exploring all methods of struggle and all forms of alliances to end this repression.

After Lincoln was forced to declare the abolition of slavery during the American Civil War (1861-65), blacks in the northern states joined the union armies and in the south fled the plantations to join the fight. Blacks were often the most determined soldiers and made up a higher proportion of the union armies than their size in the population.

Although slavery was abolished, the vicious ‘Jim Crow’ system perpetuated racism in the southern states. ‘Jim Crow’ was the term used to describe the state laws passed from the 1890s to segregate blacks from whites in the south, in schools, housing, public transport, and other areas. All kinds of measures, from poll taxes to open intimidation, were used to keep blacks from registering or exercising their right to vote. This system was absent in the north, but there the capitalist class employed the tactics of divide and rule to put black workers in the worst paid jobs in the factories.

War brings radicalisation, and the second world war in particular radicalised blacks, who were forced to fight in segregated units. Prior to the war many blacks had been influenced by the major trade union struggles that had taken place in the 1920s and 1930s, especially the massive wave of strikes that broke out in 1934, which included sit-down action and city-wide general strikes (the Teamsters’ rebellion in Minneapolis and the Auto Lite sit-down in Toledo, Ohio). Mass organising campaigns among factory workers and wider layers of unskilled workers gave rise to the Congress of Industrial Organisations (CIO), formed in 1936. The new industrial unions (United Automobile Workers, United Mine Workers, United Steel Workers, etc) involved black workers (immediately attracting over 500,000 black members), unlike the old craft unions of the American Federation of Labor. This experience was used to good effect during the war, for example, in the 1941 strike organised by the black railway porters union, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, which forced the government to end open racial discrimination in federal war production factories.

The pre-war struggles and the events of the second world war set the conditions for the development of a mass civil rights movement, beginning in the early 1950s, that would last nearly three decades. It brought to the fore some of the most courageous US black leaders and inspired workers, youth and the oppressed to struggle, not just in the US but around the world.

One of the most celebrated figures linked to this movement is Mohammad Ali, born Cassius Clay, in January 1942, to a poor working-class family in Louisville, Kentucky, who became probably the greatest heavy-weight boxer of all times. The young Clay, who took the name Mohammad Ali when he acknowledged his membership of the black nationalist Nation of Islam in 1964, was forced to take on the world, not just as sportsman but as part of the struggle for black rights. His successes became a powerful symbol of defiance and pride for black Americans and oppressed people around the world.

Systemic Racism

KENTUCKY ITSELF WAS considered the gateway state to the south. But for blacks, this was no halfway house; the repression of Jim Crow was the same as the Deep South states. White terror gangs such as the Ku Klux Klan brutally enforced segregation. In Mississippi there were over 500 lynchings between 1864 and 1955 according to official figures. In Georgia lynchings were so common they often went unrecorded.

In the summer of 1955 a 14-year-old Detroit schoolboy, Emmett Till, while visiting relatives in Mississippi, was brutally murdered for whistling to a white female cashier in a shop. His mother decided his coffin would be left open for the funeral to show the world his mutilated body. Despite this an all-white jury acquitted the murderers. A mood of determination to defeat segregation and Jim Crow gripped Southern blacks.

An early battleground in the struggle against segregation was the transport system, where blacks would be forced to give up their seats for whites, were segregated into ‘blacks only’ seats, and were routinely abused by drivers, who would call them ‘nigger’ and ‘ape’. When in 1955 Rosa Parks, a department store worker, refused to give up her seat to a white man, the Montgomery bus boycott began, bringing to the fore Martin Luther King, who became the pre-eminent leader of the civil rights movement (until his assassination in 1968). The mass boycott started the mass movement across the south to end segregation. By 1956, the Montgomery buses were desegregated, but the boycott tactic had spread not just to other public services but into industry. A sacked black steelworker was re-instated after a boycott in his factory in Birmingham, Alabama, spread to others in the same company. This forced the CIO union leaders to join the campaign to end segregation.

Influenced by these events the young Cassius Clay attended a number of civil rights demonstrations. After a white woman soaked him on one of these marches, however, he declared “that’s the last one of these I’m coming to” – although throughout the course of this struggle marchers faced that and more, in beatings, police dogs, bomb threats and shootings.

As events moved forward, however, Ali was forced to make a stand. Professional sports, and boxing in particular, had at times reflected and impacted on the battle against US racism. Before it was professionalised, slave owners often used to pit ‘their man’ against another slave owner’s for sport and gambling and when boxing was professionalised, the white champions would refuse to fight black challengers. When Jack Johnson, the first black heavyweight champion, won the title in 1908, the radical Jack London (who was unable to shed his own racial prejudices) coined the term ‘Great White Hope’ for a white to defeat him. Jim Jeffries, a previous champion who’d refused to fight blacks, came out of retirement ‘for the sole purpose of proving that a white man is better than a Negro’. Johnson inflicted a humiliating defeat on Jeffries, despite the crowd chanting ‘kill the nigger!’ Blacks celebrated across the US, but racist reaction was out for lynchings. The worst rioting of the decade followed.

Baseball was segregated before the second world war and, in order to move upmarket, American Football imposed a ban on black players from 1934 until the 1950s. But even as segregation in sport began to end, US sports owners were careful to cultivate black stars that wouldn’t buck the system. Jackie Robinson, the first black baseball star, testified in McCarthy’s notorious House Un-American Activities Committee against Paul Robeson, the world famous bass singer and supporter of the American Communist Party, helping to provide ammunition for the anti-Communist witch-hunt.

Searching for Solutions

WHILST THE MASS civil rights campaign was determined, the youth were preparing to go further. In 1960 the Student Non-Violent Co-Ordinating Committee (SNCC) was formed, which was more militant than King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference. They organised further boycotts of lunch counters, freedom rides and demonstrations against segregated schooling.

Cassius Clay, however, had been attracted to the Nation of Islam, from his days as a schoolboy (his teacher refused to let him do a project on them). This multi-million-dollar organisation that amassed real estate, jewelry and luxury cars, was a direct descendant of Marcus Garvey’s United Negro Improvement Association. (Garvey, a pioneer of black nationalism in the US, advocated a ‘back to Africa’ movement and also attempted to promote black businesses in the US). Ali’s father, Clay senior, was familiar with Garvey’s views and regularly spoke about them at home.

The Nation would have remained a sect, however, had it not been popularised by its radical leader Malcolm X. The Nation vehemently opposed participating in the mass civil rights movement, calling instead for self-containment and separation of blacks from ‘white’ America.

But the mass events taking place had a profound effect on Malcolm X, even as he maintained his loyalty to the leadership of the Nation. In 1962 Los Angeles police invaded Mosque 27 and one of its leading members was shot and killed. Malcolm X was prevented by the Nation’s leadership from launching a defence campaign even though he had conducted a vigorous investigation and started to organise a powerful alliance of black groups and oppressed workers’ organisations. He also supported a union boycott of a firm in New York that refused to hire black workers, against the wishes of the other Nation leaders.

Malcolm’s activism, his support for involvement in the mass struggle for black rights and, especially, his increasing concern with economic and class issues, brought him more and more into conflict with the Elijah Muhammad leadership. He was increasingly critical of the idea of black separation and was moving towards a position of solidarity with the white working class. In the end, the Nation’s leadership organised his assassination, with the collusion of the US law-enforcement agencies. Despite the close friendship that had grown between Malcolm X and Mohammad Ali, before Ali faced Sonny Liston for the world championship in 1964, the political split within the Nation separated Malcolm and Ali, whose political inclinations were closer to Elijah.

In explaining his conversion after his shock victory over Liston, Ali exposed the racist nature of the US. But he also declared his support for the Nation’s brand of segregation:

“I ain’t no Christian. I can’t be, when I see all the coloured people fighting for forced integration getting blowed up. They get hit by stones and chewed by dogs and they blow up a Negro church and don’t find the killers. I get telephone calls every day. They want me to carry signs. They want me to picket. They tell me it would be good for brotherhood. I don’t want to be blown up. I don’t want to be washed down sewers. I just want to be happy with my own kind.

“I’m the heavyweight champion of the world, but right now there are some neighbourhoods I can’t move into. I know how to dodge booby traps and dogs. I dodge them by staying in my own neighbourhood. I’m no troublemaker. I don’t believe in forced integration. I know where I belong. I’m not going to force myself into anybody’s house…

“I love white people. I like my own people. They can live together without infringing on each other”.

Ali, having embraced the religion and at the same time conquered the boxing world, now became the most famous member of the Nation of Islam. He also became the centre of a power struggle within the Nation itself and, at the same time, a major cause of discussion in the civil rights movement. Two men publicly congratulated him on his victory over Liston: Malcolm X and Dr Martin Luther King. Jackie Robinson meanwhile commented that Ali’s conversion meant ‘nothing’ to the civil rights movement and put his trust in liberal whites to win the day. But Robinson also warned that, “if Negroes ever turn to the Black Muslim movement in any numbers… It will be because white America has refused to recognise the responsible leadership of the Negro people and to grant us the same rights that any other citizen enjoys in this land”.

Ali’s world title defence against Floyd Patterson in November 1965 was preceded by a war of words between the two – not the usual pre-fight hype but a bitter political battle about the way forward. Patterson, who even offered his purse to the liberal-reformist National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), stated: “I have the right to call the Black Muslims a menace to the US and a menace to the Negro race… If I were to support the Black Muslims, I might as well support the Ku Klux Klan”. He reflected the thinking of a layer of blacks who at that stage believed that white American liberals would ‘come to their senses’. By this time, Ali had all his affairs controlled by the Nation and pledged:

“I’m gonna put him [Patterson] flat on his back,

So that he will start acting black,

Because when he was champ he didn’t act like he should,

He tried to force himself into an all-white neighbourhood”.

‘I ain’t got no quarrel with them Vietcong’

JUST AS THE black movement leaders had to draw conclusions about the way forward, so did Ali in his battle with the US state. The Civil Rights Act was passed in 1965 but the struggle for more than just voting rights continued. One key issue was the developing war in Vietnam.

In 1965 a poll showed 84% of blacks opposed the war but disproportionately more blacks were being drafted into the army to fight in Vietnam. The youth involved in the civil rights movement under the leadership of SNCC came out against the war in Vietnam.

Early in 1966 Ali was classed as eligible for call-up but he refused to be conscripted into the army, asserting that he was a conscientious objector on religious grounds. His ringing declaration in response to the draft – “Man, I ain’t got no quarrel with them Vietcong” – catapulted him into the forefront of the then infant anti-war movement. Ali attended the infamous Los Angeles demonstration – in which 200 demonstrators were clubbed by the brutal Los Angeles Police Department – albeit in his Rolls Royce! He took part in speaking tours around the college campuses.

In 1967 Ali was sentenced to five years in jail for refusing to accept the draft, and the World Boxing Association (WBA) stripped him of his title. Eventually, in 1970, the conviction was overturned by the supreme court (which upheld his right to be a conscientious objector on religious grounds), and the WBA had to reinstate him.

Martin Luther King was also changing his position as riots ripped through most of the country’s black ghettos between 1964 and 1968. Amidst the rubble of the Watts riots, King declared, “It was a class revolt of the under-privileged against the privileged”. In 1967 he was forced to conclude: “We have moved into an era which must be an era of revolution… what good does it do to a man to have integrated lunch counters if he can’t buy a hamburger?” Over those four years 250 mainly black protestors had been killed, 10,000 were injured, and 60,000 had been arrested.

The pacifist movement for civil rights begun in 1954 with a peaceful boycott was developing into a class war. The more far-sighted leaders had started to conclude that the struggle for black liberation was intimately connected to the struggle of the working class. The youth in particular strove for this understanding and the most determined representatives of the movement, the Black Panther Party, adopted some elements of Marxism.

Ali himself found that all the money and fame he had amassed did not isolate him from this struggle. Like Tommie Smith and John Carlos, 200 metre gold and bronze medallists at the 1968 Olympics, who raised clenched black-gloved fists on the winners’ podium, Ali was inspired by a mass movement that had rocked US capitalism and given blacks a glimpse of their power. Eventually allowed to box again, he recaptured the title with a brilliant mastery of tactics (including gaining the support of the Zairian masses, where the fight was being held) in the 1974 encounter with the apparently invincible giant, George Foreman.

Undoubtedly the US authorities feared the potential impact of a politically active Ali at this time, following the defeat in Vietnam and the Watergate scandal that unseated the disgraced president, Richard Nixon. Later, governments tried to use Ali for their own purposes including, in 1980 under president Jimmy Carter, sending him as a political emissary to Africa to win support for the US boycott of the Russian Olympics (the trip was a disaster for Ali and he feared he was being manipulated). As a powerful political symbol of black defiance, the state has been forced to incorporate his legend into its re-writing of history.

Despite this, however, when blacks in the US are forced into struggle, the youth and the new leaders who will come forward will continue to take inspiration from Ali’s determination. He inspired millions around the world, especially those from the ex-colonial world.

While touched by these events, however, and propelled into taking action, Ali never drew the link with the workers’ movement and the critical importance of collective struggle. I can still remember in one of his interviews with Michael Parkinson how he described how proud he felt driving through ghettos like Harlem in his Rolls Royce and how he believed he presented a positive black role model, urging young black men not to take up boxing but to take up studying.

But times have moved on and the vast majority of blacks in the US still face poverty, unemployment and slum housing. The ruling class and many black leaders still consider that positive ‘role models’ for black youth, rather than organising and campaigning, are the most important way of providing guidance away from a life of poverty, drugs and crime. But as Malcolm X and Martin Luther King were discovering, black youth will be forced to go the whole way and link the struggle to end racism with the struggle for socialism.