Paul Kershaw is a member of the Socialist Party (CWI in England & Wales).

Big business is increasingly taking over the housing sector – social rented as well as private ownership. The results have been devastating as tenants face sky-high rents, fewer rights, worsening conditions, and government policies of aggressive deregulation.

This article reviews two books linking the current housing crisis with globalisation and the financial markets.

Big business is increasingly taking over the housing sector – social rented as well as private ownership. The results have been devastating as tenants face sky-high rents, fewer rights, worsening conditions, and government policies of aggressive deregulation.

This article reviews two books linking the current housing crisis with globalisation and the financial markets.

- The Financialisation of Housing: a political economy approach, Manuel B Aalbers, Routledge, 2016

- In Defence of Housing: the politics of crisis, David Madden and Peter Marcuse, Verso, 2016

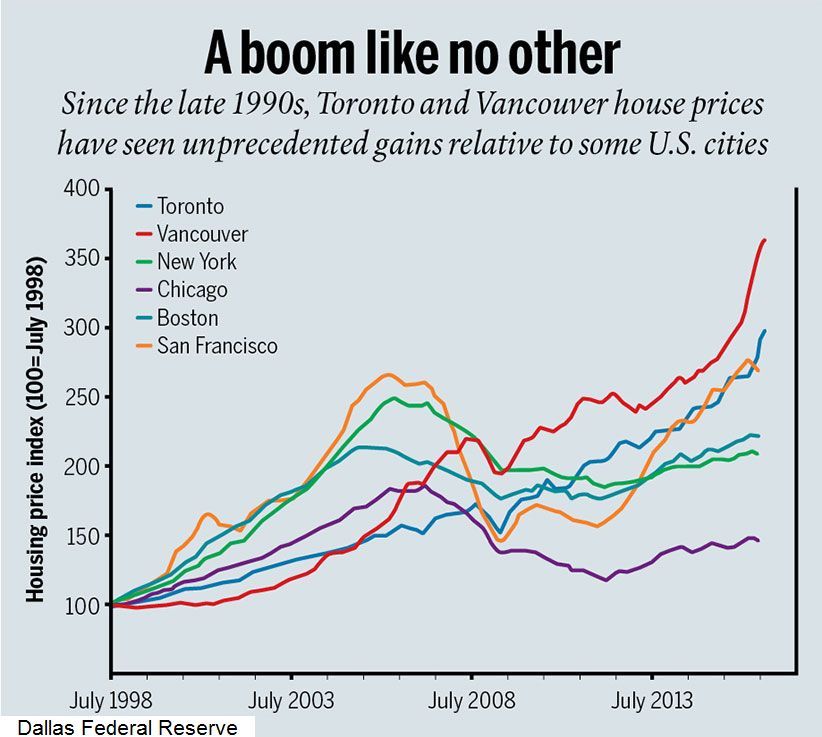

The financial crash of 2007-08 started with bad home loans. Countless home-owners in the US and elsewhere found themselves booted out of their homes while the banks were bailed out. Both these books chart a worldwide crisis – the 21st century housing question. Following the global financial turmoil of 2007, Manuel B Aalbers comments: “Never before had so many housing markets entered a crisis at the same time”. His book gives many valuable statistics and insights into the nature of the current crisis.

David Madden and Peter Marcuse concentrate on New York, but with international examples give a vivid outline of the human impact of the crisis and important examples of campaigns on housing. They also give a useful historical perspective. Writing about the position today, they explain: “The form of the housing crisis is different in Manhattan than in the foreclosed suburbs of the American southwest, the bulldozed shacklands of South Africa, the decanted council blocks of Great Britain, and the demolished favelas of Brazil. But they have a common root: they are all situations where the pursuit of profit in housing is coming into conflict with its use for living”.

They cite research showing that, in recent decades, residential displacement due to development, extraction and construction has reached a scale rivalling that caused by disasters and armed conflict. It is estimated that 350 million households around the world – more than a billion people – are unable to find a decent or affordable home. As they put it: real estate is attacking housing and the social use of housing is subordinated to its economic value.

Karl Marx explained 150 years ago that “products are only commodities because they have a dual nature, because they are at the same time objects of utility and bearers of value”. (Capital, Volume One) Madden and Marcuse argue that interlocking processes of deregulation, financialisation and globalisation mean that housing now functions as a commodity to a greater extent than ever before, and this is what lies at the heart of the housing crisis.

Today it might be hard to imagine that housing could be organised in any other way than as a commodity produced for sale. However, Madden and Marcuse point out: “… in the history of human settlements, the commodity treatment of dwelling space is relatively new”. In earlier times, housing was not an independent sector of the economy but a by-product of broader social relationships and exploitation. As capitalism developed, traditional tenures were destroyed and common land enclosed in a process Marx called ‘primitive accumulation’. As he put it, the process is “written in the annals of mankind in letters of blood and fire”. Pushed off the land, the poor were ‘free’ to work for capitalists or starve. Through a complex series of steps land became ‘alienable’, a commodity to be bought or sold.

Madden and Marcuse explain that this brutal process, which was carried out by an alliance of the landed aristocracy, large manufacturers and the ‘bankocracy’ in Britain, laid the basis for the eventual “commodification of land on a planetary scale” through colonialism. By the mid-19th century, western cities had an industrial proletariat that was no longer housed at its place of work. Cash payment became the nexus between house and householder; the conditions for the commodification of housing had emerged. This was the basis for the shocking conditions described by Friedrich Engels in The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844.

The role of the state

By the first decades of the 20th century growing mass unrest focused around the “social disaster” resulting from the “commodification of dwelling space”. One outcome was the creation of decommodified housing, such as council housing in Britain. Governments also moved to create new financial and legal structures that made the standardised mortgage and mass home ownership possible. Far from home ownership being the natural order of things, or the result of the state standing aside, it came about through state action. Even in the US, it was only after the second world war that home ownership reached a majority.

Mass home ownership had an ideological role in stabilising capitalism and it opened up new avenues of capital accumulation. Madden and Marcuse explain that, contrary to the myth of a benevolent state attempting to solve housing problems for the common good, “… the state has used the housing system to preserve political stability and support the accumulation of private profit”.

Aalbers also outlines key historical developments although he underplays the role of political struggle and class forces. Nonetheless, he does bring out clearly that the development of mass mortgage markets for home ownership was facilitated by the active involvement of the state. In addition, that what is often referred to as the deregulation of financial markets of recent decades entailed facilitating a free-for-all in financial markets. The financial ‘innovation’ that followed, which helped fuel the growth in ‘securitisation’ – whereby mortgage debts could be sold on and traded by the organisation that sold the mortgage in the first place – rested on policy moves by the state.

Securitisation had been developed in the US in the late 1960s and early 1970s when new legislation allowed the government-created agencies, Fannie Mae (set up in 1938) and Freddie Mac (created in 1970), to promote home ownership. The innovations of recent decades, however, opened up the way to an exponential increase in investment from sources around the globe. Investment banks used the process to fund subprime and predatory lending. The binding together of low-risk and high-risk loans into securities, which were all rated low-risk by the compliant rating agencies, appeared to magically abolish risk for speculators seeking higher yields from their investments. The increased finance for housing may have drawn more people into home ownership but it also served to drive up the price of homes. Home buyers were directly connected to the volatility and uncertainty of stock markets and other financial markets.

A global wall of money

Both books argue that a process they describe as financialisation characterises capitalism today and dominates the housing sector. It is a term that has been used with different meanings but it points to the increasing prominence of people and companies that engage in profit accumulation through the servicing and exchanging of money and financial instruments. Rather than being restricted to banks and traditional financial institutions, this activity becomes all pervasive. Workers are drawn into this through credit cards, mortgages, etc. The fact that the global financial crisis could be triggered by the poor being unable to repay loans is a stark illustration of this.

According to Aalbers, a “global wall of money” has built up and is “looking for high quality collateral (HQC)”, a global pool of liquid assets whose owners seek safe investment opportunities. Housing is one of the few asset classes considered HQC. The other side of this, of course, is that investors are not willing to invest in the more risky business of making things and employing people to do so. The global wall reflects over-accumulation (the capitalists’ increasingly restricted ability to find profitable fields of investment in production) and the wider malaise of contemporary capitalism.

Four sources of this global wall are identified: institutional investors, ‘pension fund capitalism’; recycling of the trade surpluses of ‘emerging economies’; quantitative easing and loose money policies supposed to kick start the world economy after the crash; and the accumulated profits of multinational companies stashed away in tax havens that amount to roughly 30% of global GDP. Aalbers observes that the growing pool of ‘corporate savings’ arises from the improved profit share that is the flip side of the decline in the global wage share. This fourth source is a direct result of over-accumulation and all are embedded in the current depressionary phase of capitalism.

This massive increase in credit had to be secured against. Looked at as an asset, housing has played a crucial role as collateral for debt. Aalbers quotes a survey showing that from the 1970s to 1980 private debt was around 50% to 60% of GDP (the economies’ output) in a group of economically advanced capitalist countries. By 2010 it had rocketed to 118% of GDP. Mortgage loans increased as a percentage of GDP from 20% to 64% in the same period; the boom in debt was clearly heavily based in property. High house prices play an important role in capital’s attempt to stave off crisis. This is the key priority for capital – not ensuring decent affordable housing.

Housing stock sell-off

Home ownership levels have been falling in many countries as high prices and a lack of secure well-paid jobs push it out of reach. However, Aalbers explains that the global wall seeks profitable outlets in rented housing. In the US and elsewhere, hedge funds, private equity companies and the like are investing in rented accommodation. They often prove to be very bad landlords, and Madden and Marcuse give striking examples from New York.

In the first decade of the 21st century, private equity firms acquired around 10% of the city’s ‘rent-stabilised’ housing stock, approximately 100,000 homes according to Aalbers. Sometimes they starve property of investment so it falls into disrepair. Other times they use targeted investment to push the property out of the rent-stabilised sector. Tenants have mounted fight-backs but the complex of ownership and management arrangements often makes it hard to pin down responsibility. In the past, slum landlords were typically from the middle classes. Now, the big financial institutions increasingly play that role.

The global wall of money has had a varied impact in different countries. Germany has resisted speculative booms in owner occupied housing due to the structure of its finance sector and restrictions on income multiples for loans, etc. But the global wall has found a way in through the rented sector. Berlin, with its large public housing stock – and because of the city’s acute budgetary crisis – was a prime target, but the process has reached across the country. In Berlin the state parliament agreed the sale of 50,000 housing units in 2000. A red-red coalition (of the former social-democratic SDP and the PDS, forerunner of Die Linke) took office in the city in 2001 but scandalously continued the policy. What a contrast to the Militant-led Liverpool city council in the 1980s which, in defiance of Margaret Thatcher’s Tory government, was responsible for most of the council houses built in the country at the time.

In the Netherlands, the large housing association sector was progressively deregulated and became increasingly financialised. One large association, Vestia, became to all intents and purposes a financial derivatives trading house. When its bets went wrong it effectively went bust. In 2014 it set out a strategy which included cutting operating costs (staff, etc) by 15%, selling 32,000 of the 90,000 homes it owned, and increasing rents. This is a real warning for tenants and residents in England, given that an important provision of the Tories’ new housing act is the further deregulation of housing associations.

Even when a housing association is profitable it is in the nature of the business to take risks. Particularly in the event of renewed financial turmoil, the risks can crystallise. The associations borrow on the basis of homes with tenants – whose rents generate a steady flow of income – and it is possible that creditors would end up owning the homes. Aalbers cites the case of Cosmopolitan Housing which had to be rescued. At the time of the financial crash in 2007-08, however, a number of large English housing associations were close to insolvency because of problems with their financial derivatives.

Cash rich housing associations

In Britain, Aalbers argues that a shrinking market for mortgage-backed securities resulted in a search for new high quality collateral with investors becoming increasingly interested in social housing bonds issued by housing associations. His broad analysis illuminates what is happening in the sector now. Housing associations are being funded more and more by bank loans or bonds, and increasingly behave as financialised property corporations. For some, social rented housing already forms less than half their turnover.

Many of the big international investors in rented housing in Germany and the US are UK based and, sometimes, among the big donors to the Tory party. Some, such as the private equity firm Terra Firma set up by tax exile Tory supporter Terry Hands, already have direct investments in Britain’s private rented sector. They also look to invest in housing associations or, potentially, to buy their stock.

In 2015, we reported that the Genesis Housing Association had announced it was no longer interested in the social rented sector. It sponsored a report by the influential right-wing think-tank, Policy Exchange, calling for deregulation. The new Housing Act gives far greater ‘freedoms’ to housing associations. They can, for example, sell housing stock without prior consent from the regulator.

Last year’s struggle by tenants of the Butterfields estate in Waltham Forest, east London, illustrates what could happen. There, social rented housing owned by a small unregulated charity was sold and tenants were threatened with massive rent hikes or eviction. In a campaign based on refusing to move, in which the Socialist Party played a key role, tenants fought back successfully. Their properties were taken over by another housing charity, allowing them to stay. At that time, the Butterfields charity was exceptional in that it was not being regulated. Now all associations are in that position.

UK housing associations are extremely healthy financially despite the impact of welfare cuts on their tenants’ ability to pay rent. In 2016 the sector recorded a surplus of £3.4 billion which follows a string of record surpluses. A survey conducted by the accountancy firm RSM for the Inside Housing magazine found that ‘economic sentiment’ in the sector is the highest since the financial crash. However, the chief executive of Hyde Housing has said that she thinks associations are guilty of creating a dependency culture by doing too much for their residents! Hyde tenants are currently battling to save a number of community centres the company wants to close on south London estates.

Housing associations are well placed to play a key role in major ‘regeneration’ schemes which often result in a loss of social housing and the destruction of working-class communities. Madden and Marcuse point to a large scheme planned in Tottenham, north London, by the local Labour council. Even the Guardian newspaper’s right-wing Labour supporting Polly Toynbee has expressed outrage at the scheme. Of the three consortia that bid for the regeneration, two included a significant participation by two major housing associations: Catalyst and Clarion. Neither was selected, although that was not primarily because their plans included more social housing. Unite the Union criticised the council for opting for Lend Lease which has a history of blacklisting trade unionists. However, the other two housing associations are not much more preferable from an employment point of view. Catalyst de-recognised trade unions some years ago and Clarion is in the process of de-recognising Unite.

A political issue

The question of accountability and the regulation of housing associations could be a key political issue in Britain. A series of scandals highlighted by the Guardian in which new-build housing association properties have been plagued by damp, rats and problems with sewage has prompted calls for tighter regulation. This has led to criticism of an overly commercial approach.

The real strength of Aalbers’ book is to demonstrate that the global housing crisis is unprecedented and driven directly by the current crisis of capitalism, and not by this or that unfortunate policy. But, as he concedes, his own policy prescriptions are very limited although he does assert the value of building cheap rented housing. Madden and Marcuse make a call to “prevent housing from being treated as a commodity”, and make proposals for ‘transformative’ reforms and more public housing.

Earlier this year, we reported on a successful campaign by Kshama Sawant, the Socialist Alternative councillor elected in Seattle, Washington. As a result money was diverted from a planned police station and $29 million will provide nearly 200 homes. The campaign also helped Kshama pass ground-breaking tenant rights legislation, capping move-in fees and requiring landlords to offer payment plans.

A commitment to rent control, to provide more council housing and end regeneration schemes that result in a loss of social housing were important demands that attracted people to Jeremy Corbyn in his campaigns for election and re-election as leader of the Labour Party. A failure to build on that and campaign actively around these demands, however, could result in the demoralisation of the new members brought into Labour over the past two years. On the other hand, any Labour council campaigning on this platform and setting a needs budget to put it into action would get an enthusiastic and massive response.

Marxists will take up and build support around immediate demands, such as residents refusing to move out of their homes as a result of misnamed regeneration schemes, against exploitative landlords, and for campaigns for more public housing. In this time of capitalist economic crisis, it is also particularly important to link them to the need to nationalise the banks and financial system so that resources can be directed for social need.

Big business is increasingly taking over the housing sector – social rented as well as private ownership. The results have been devastating as tenants face sky-high rents, fewer rights, worsening conditions, and government policies of aggressive deregulation.

This article reviews two books linking the current housing crisis with globalisation and the financial markets.

Big business is increasingly taking over the housing sector – social rented as well as private ownership. The results have been devastating as tenants face sky-high rents, fewer rights, worsening conditions, and government policies of aggressive deregulation.

This article reviews two books linking the current housing crisis with globalisation and the financial markets.