Alan Jones is a member of Socialist Alternative in the US.

At the end of June, amid a growing discussion about socialism in the US, Bhaskar Sunkara wrote an important op-ed in the New York Times entitled ‘Socialism’s Future May Be Its Past’. ALAN JONES wrote a contribution on behalf of Socialist Alternative. This is an edited version – the full article is here, from the CounterPunch website.

Bhaskar Sunkara, editor of Jacobin magazine and a vice chair of Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), attempts to draw out lessons from the Russian revolution and take up the relevance of socialist and radical ideas in our time. It was a distinctly different and more sympathetic assessment than other recent articles in the same publication addressing the 100-year anniversary of that historic event. As one point of comparison, a week earlier, the New York Times printed an article by right-wing author Sean McMeekin which sought to revive the long ago discredited ‘Lenin was a German spy’ conspiracy theory.

It should come as no surprise that a large section of the mainstream media and pro-capitalist commentators are again devoting time and resources to distort and discredit socialist ideas, including no less than the president of the US Chamber of Commerce, as Sunkara points out. This distortion campaign is a response to the revival of socialism which has begun to take place in the US on the heels of the incredibly popular campaign of Bernie Sanders.

Sanders called out for a ‘political revolution’ against Wall Street and the 1%, and in so doing galvanised millions of workers and young people who have been radicalised by the deep social crisis of capitalism and have begun to question the viability of the system. An estimated 1.3 million people attended Sanders’ mass rallies. In another welcome development, left and socialist organisations like Socialist Alternative have grown rapidly. The DSA has grown from roughly 8,000 to nearly 25,000 members since Trump was elected last November.

In his op-ed, Sunkara generally defends the Russian revolution as a positive development, and the mere fact of the article being published in the US ‘paper of record’ is itself a sign of the changing times. As Sunkara’s article suggests, to turn the tide against the bankrupt status quo today we will need to learn the key lessons from the history of the global working-class movement. We must equip ourselves with the best ideas in order to defeat Trump and the worldwide capitalist offensive on our living standards and democratic rights. Unfortunately, in his article Sunkara does not offer a rounded-out socialist alternative. Instead he seems to argue that a ‘regulated market’, a foundation stone of capitalism, should continue in the society socialists should be striving to create.

There is an important tradition of socialists having a fraternal discussion on important issues of strategy, tactics and program. This has played an essential role in educating socialists, other activists and the general public about the best methods to change society. We offer this article as part of that tradition, not to distort points of view, but instead to contrast different approaches to issues.

Sunkara’s three stations

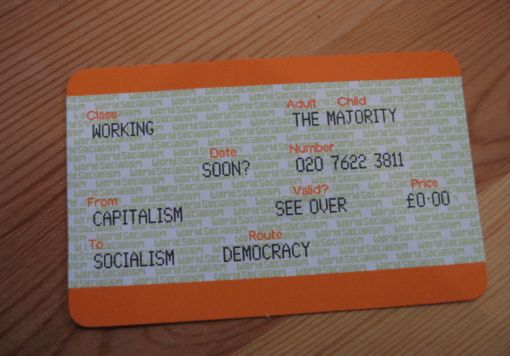

Bhaskar paints a picture of the key trends that dominate the politics of the capitalist class today. One is the ‘Singapore station’ which he casts as the logical conclusion of the politics of mainstream neoliberals like Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama. A second, ‘Budapest station’, represents the ultimate destination of right-wing populism like Donald Trump’s. The third, ‘Finland station’, is of course the main subject of his article and a reference to the Russian revolution and Vladimir Lenin’s historic train journey back from exile in early 1917.

Sunkara’s critique of neoliberalism in the Singapore station section makes important points, but also reveals limitations in his approach. While acknowledging its undemocratic character and relentless drive for neoliberal austerity, he portrays it as relatively benign and “not the worst of all possible endpoints”.

This dramatically understates the character of neoliberalism and the results of its worship of unrestrained capitalism: the vicious driving down of workers’ living standards in the name of profit, the loss of access to vital services like healthcare, the loss of millions of lives from wars over resources, the many and varied disasters of deregulation (like that recently at Grenfell Tower in London), and to neoliberalism’s complete inability to offer a future for youth and working people around the world.

It is precisely this model’s instability and brutality that opens the door to the Budapest station of right-wing populists like Trump – and authoritarian regimes in Hungary, Poland and elsewhere – in the desperate search of middle- and working-class people for some alternative to the dominant ‘Singapore’ route of capitalism.

Sunkara gets into what his own Finland station vision of socialism would look like. He explains that it would entail “worker-owned cooperatives, still competing in a regulated market; government services coordinated with the aid of citizen planning; and the provision of the basics necessary to live a good life (education, housing and healthcare) guaranteed as social rights. In other words, a world where people have the freedom to reach their potentials, whatever the circumstances of their birth”.

Without a doubt, such changes would represent a significant step forward despite being under threat of attack every time capitalism entered into one of its periodic crises. But this is not the same as the goal of socialism: a global, classless society which does away with capitalism’s organised apparatus of repression and replaces it with a new political order based on mass democratic organs of working people and the oppressed.

This has always been the destination called for by the socialist and Marxist movement. Many today, even on the left, may see this vision as hopelessly utopian. But, as Marx argued, it is the massive development of human productivity under capitalism which has laid the material basis to eradicate class division and oppression rooted in scarcity.

Marxism and the state

Sunkara states: “Stripped down to its essence, and returned to its roots, socialism is an ideology of radical democracy. In an era when liberties are under attack, it seeks to empower civil society to allow participation in the decisions that affect our lives”. Yet a central tenet of Marxism is that capitalist democracy is only a form of state rule. And Marx argues the dominant class in society is the one that controls the state apparatus. Marxists have long championed the most far-reaching, radical democracy. But Marxism has also explained that democracy does not exist in abstract. It must be understood in connection with the dominant economic system.

Under capitalism, democracy is always severely curtailed by the domination of the small propertied elite who use their power to prevent the majority from touching the foundations of their wealth and privilege. In other words, championing ‘radical democracy’ can only be done consistently if it is linked to ending the undemocratic rule of the capitalist class and transferring power into the hands of the working class and the oppressed.

Sunkara does not clarify this. In his ‘broad outline’ of a future socialism, which is dominant – market forces or the workers’ cooperatives? Sunkara states: “This social democracy would involve a commitment to a free civil society, especially for oppositional voices; the need for institutional checks and balances on power; and a vision of a transition to socialism that does not require a ‘year zero’ break with the present”.

However, if we are talking about ending the brutal and decaying capitalist system, how can this be done without having a fundamental, thoroughgoing break with the present order and its deeply undemocratic and repressive state apparatus? Instead, it appears that Sunkara is arguing against this when he says his vision of a transition to socialism does not require a ‘year zero’ break with the present.

It was this central point that Lenin argued for when he returned to Russia in 1917. Lenin stated that the feeble capitalists in Russia could not and would not deliver benefits for the working class. He called for the working class and poor peasants to break the power of the landlords and capitalists over society, and appeal to workers in other countries to follow this example and begin the construction of a socialist society based on workers’ democracy.

Fighting for reforms

As Marxists, we in Socialist Alternative fight for every gain that working people can win under capitalism. This can be seen in our leadership in the fight for $15, with Socialist Alternative member and Seattle city councilwoman Kshama Sawant leading Seattle to become the first major city to pass a $15 minimum wage. Two weeks ago, we helped make Minneapolis the first Midwest city to pass $15, this time under the leadership of socialist city council candidate, Ginger Jentzen. And just last week, Sawant and Seattle Socialist Alternative helped bring about another nationally important victory, this time a local measure to tax the rich to help fund affordable housing, education and other vital services.

In April, Kshama Sawant responded to questions in the Huffington Post about her views on socialism: “There are limits to reforming a system that is dominated by these massive and rapacious corporations. On the basis of capitalism, victories like raising the minimum wage are only temporary. Big business has many tools to make us pay for the crisis of their system. Again, a permanent and sustainable solution to all the problems facing working people is possible only by taking the biggest companies into democratic ownership, and reorganising the economy on a planned basis. Under such a system we could democratically decide how to allocate resources. We could rapidly transition away from fossil fuels, develop massive jobs programs to rebuild the country’s rotting infrastructure, and begin to build a whole new world based on meeting the needs of the majority, not the profits of a few”.

The issues raised by Sunkara about reform and revolution are not just abstract questions of historical interest. Which station we end up at today is intimately linked to how we assess the defeats and successes of the past.

After the second world war – an era of post-war reconstruction and huge economic growth, and under the enormous pressures of mass socialist and communist parties and radical labour struggles – important gains for working people were won in most western countries. But the tenuous economic landscape of today is radically different, with capitalism incapable of enjoying a sustained upswing, relentlessly attacking unions and working conditions, and demanding deep budget cuts in order to just maintain profitability and survive.

The new parties of the left can end up at a neoliberal Singapore station in the present, even as they look to the Finland station of the past, if they fail to draw the correct lessons. If left parties are elected to government without a definite program for an alternative to capitalism and a strategy to achieve it, they will inevitably be driven instead into attempting to manage capitalism. This can mean carrying out neoliberal austerity dressed up with kind words of compassion. Reform-minded, anti-austerity governments will ultimately be forced to choose between accepting the demands of big business or implementing radical and socialist measures.

As Rosa Luxemburg explained in 1900 in her pamphlet Reform or Revolution these two choices are not just ‘different roads’ to the same station. To be successful, the struggle for reform cannot be an end unto itself – serious reforms only come about as a by-product of serious social struggle. The capitalist class needs to be genuinely fearful of a wider revolt before it will grant major concessions like Medicare for all or a federal $15 minimum wage.

Further, if the struggle for reform is not used to develop the consciousness of working people and prepare the ground for a thoroughgoing socialist transformation of society, the capitalists will look to roll back the reforms which have been won, or to destroy those working-class forces which defend them. The ruling class will not hesitate to engage in economic war or even military coups against elected left governments. Left governments seeking to carry out their programs will run headlong into the brick wall of capitalist ownership and control of the key resources in society, as well as the capitalist state apparatus. This can be clearly seen in what happened to Syriza in Greece. To effectively fight against austerity in a time of capitalist crisis we need a Marxist program for fundamental change, and a plan to mobilise workers, young people and the poor to fight for it.

Bolshevism is not Stalinism

If genuine socialist ideas are to once again become the international rallying cry for a new society, we will have to seriously and honestly discuss the experience of the Russian revolution of 1917, the Bolsheviks, and Lenin.

The revolution shaped the entire political history of the last 100 years and represented a colossal effort to establish a new socialist world. Millions internationally were inspired to fight not just for a more ‘manageable’ version of capitalism but for a new socialist world based on solidarity, and without war and exploitation. Many of the gains and reforms working people won across the globe, including the eight-hour day, voting rights for women, free education, healthcare and a broad social safety net, came in the aftermath of the revolutionary wave unleashed by the Russian revolution.

The revolution was thoroughly democratic, with workers’, soldiers’ and peasant councils (soviets) built from below. The Bolsheviks went from being a small minority in the soviets to the leading force in the revolution through the course of 1917 by democratically winning over the masses of people to their program to defeat reaction, war and poverty.

Workers’ councils have been a feature of revolutionary struggles since the Paris Commune of 1871 and the first Russian revolution in 1905. Similar features developed in China 1925-27, the Spanish revolution 1931-37, France 1968, and Chile before the 1973 coup, just to name a few. We have seen similar examples of ‘revolutionary democracy’ in virtually every major upheaval centred on the working class across the globe.

Sunkara seems to be unaware of the democratic role of the soviets, while implying there was something fundamentally undemocratic about the Russian revolution. While appealing for a return to the Finland station, he insists that things will be different this time around: “This time, people get to vote. Well, debate and deliberate and then vote”. But the Bolsheviks did debate, deliberate and vote, quite often in fact. If they hadn’t done that, both internally and in the soviets, the October revolution would not have been successful.

The main argument of most of those who attack the Bolsheviks is that they supposedly wanted to centralise power and to eliminate all opposition. But this was not what happened in Russia in 1917 – in reality, the most democratic revolutionary upheaval that has ever taken place. It was after the Bolsheviks had come to power in October, with the overwhelming support of the soviets, that other political parties went over, one by one, to the side of the armed counter-revolution and helped plunge the country into civil war.

At the same time, 21 armies invaded the Soviet Union, including the US, Britain, France, and Japan. Alongside international solidarity, the only thing that allowed the Bolsheviks to survive the prolonged civil war, invasions, famine and destruction was the fact that they enjoyed the overwhelming support of the population who fought back against the murderous, pro-capitalist reaction.

How Stalinism developed

Leon Trotsky, who along with Lenin was a key leader of the Russian revolution, wrote that a “river of blood” separated the Bolsheviks from Stalinism. The Bolshevik party was arguably – and new historical research confirms this – the most democratic party of working people so far in history – and the most successful in leading the working class to power. Lenin and Trotsky perceived the revolution in Russia as a prelude to the European revolution and beyond. They understood that socialism could only be based on an international and voluntary federation of socialist countries, including the most economically developed. They understood that capitalism globally would fight back against a new workers’ state, and that one socialist country – particularly one as economically backward as Russia – could not survive on its own.

Stalinism did not arise from Bolshevism but from the isolation of the revolution in the young Soviet republic, famine, backward economic and cultural conditions, and the perishing of the most self-sacrificing worker leaders in the course of the civil war. The disappointment of the masses with the failures of the European revolutions was a key factor, especially in Germany 1918-23. These conditions allowed the rise of Stalinism as the Soviet officialdom increasingly controlled the use and distribution of scarce resources, thereby enabling themselves to become privileged.

A precondition for the rise of this privileged Stalinist bureaucracy was the destruction of the democratic traditions of Bolshevism, including the crushing of soviet democracy, mass repression of the Left Opposition, the extermination of virtually the entire Bolshevik Central Committee of 1917 and, ultimately, the assassination of Trotsky in 1940. The rise of Stalinism first undermined the planned economy by destroying the democracy necessary to its functioning, and eventually led to its destruction in what Trotsky explained as the bureaucracy ‘consuming’ the first workers’ state.

Not only did Leninism not usher in Stalinism, it took a bloody counter-revolution by the bureaucracy to reverse many of the democratic gains of the revolution and impede the worldwide struggle for socialism. The Communist parties around the world ceased to struggle for fundamental change, instead becoming props for Stalin and the needs of his bureaucracy, ideologically defended by his policy of ‘socialism in one country’.

Socialists will be confronted with questions about the Russian revolution and the totalitarian caricatures of ‘communism’. We need to have clear answers to these historical issues and effectively apply these lessons from 1917 to the workers’ movement today, which is operating in very different and rapidly-shifting conditions.

The continuing debate

Successfully translating mass opposition to austerity and the ills of the capitalist system into effective action against racism, sexism, war, poverty and joblessness, depends on adopting a bold fighting program, strategies and tactics. We must analyse a fast-moving situation to find the best proposals and slogans that can move people into action. This also requires workers developing their own mass independent party, democratically run, which can unite young people, the working class and poor to wage a determined struggle against the billionaire class.

History shows that ideas, program and leadership matter. Opportunities to challenge capitalism will only be fully successful if the ideas of Marxism can take hold in the working class with an organised socialist left. Socialists in the US, while starting from building a movement against the attacks of Trump and the Republicans in power, must also continue to engage in constructive debate about how to build the movement and political power for working people. Movements here will not happen in exactly the same way as in Greece the past few years or the Russian revolution 100 years ago, but there are important lessons to be learned from all these experiences.

Today the socialist movement faces dual tasks. We need to bring together socialist, progressive and fresh forces into broad and united action, struggle and resistance to defeat the right wing and the neoliberal offensive. But we also must seek to win the advanced layers of working people and youth to the understanding that a bold socialist program is the only way out of the crisis of capitalism, and of the need to build a revolutionary organisation capable of leading the fight to win such a program.

Crucial debates like this one around working-class history, international struggle, strategy and program must continue as we work together to defeat the billionaire class and rebuild a powerful socialist movement.

At the end of June, amid a growing discussion about socialism in the US, Bhaskar Sunkara wrote an important op-ed in the New York Times entitled ‘Socialism’s Future May Be Its Past’. ALAN JONES wrote a contribution on behalf of Socialist Alternative. This is an edited version – the full article is here, from the CounterPunch website.

Bhaskar Sunkara, editor of Jacobin magazine and a vice chair of Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), attempts to draw out lessons from the Russian revolution and take up the relevance of socialist and radical ideas in our time. It was a distinctly different and more sympathetic assessment than other recent articles in the same publication addressing the 100-year anniversary of that historic event. As one point of comparison, a week earlier, the New York Times printed an article by right-wing author Sean McMeekin which sought to revive the long ago discredited ‘Lenin was a German spy’ conspiracy theory.

It should come as no surprise that a large section of the mainstream media and pro-capitalist commentators are again devoting time and resources to distort and discredit socialist ideas, including no less than the president of the US Chamber of Commerce, as Sunkara points out. This distortion campaign is a response to the revival of socialism which has begun to take place in the US on the heels of the incredibly popular campaign of Bernie Sanders.

Sanders called out for a ‘political revolution’ against Wall Street and the 1%, and in so doing galvanised millions of workers and young people who have been radicalised by the deep social crisis of capitalism and have begun to question the viability of the system. An estimated 1.3 million people attended Sanders’ mass rallies. In another welcome development, left and socialist organisations like Socialist Alternative have grown rapidly. The DSA has grown from roughly 8,000 to nearly 25,000 members since Trump was elected last November.

In his op-ed, Sunkara generally defends the Russian revolution as a positive development, and the mere fact of the article being published in the US ‘paper of record’ is itself a sign of the changing times. As Sunkara’s article suggests, to turn the tide against the bankrupt status quo today we will need to learn the key lessons from the history of the global working-class movement. We must equip ourselves with the best ideas in order to defeat Trump and the worldwide capitalist offensive on our living standards and democratic rights. Unfortunately, in his article Sunkara does not offer a rounded-out socialist alternative. Instead he seems to argue that a ‘regulated market’, a foundation stone of capitalism, should continue in the society socialists should be striving to create.

There is an important tradition of socialists having a fraternal discussion on important issues of strategy, tactics and program. This has played an essential role in educating socialists, other activists and the general public about the best methods to change society. We offer this article as part of that tradition, not to distort points of view, but instead to contrast different approaches to issues.

Sunkara’s three stations

Bhaskar paints a picture of the key trends that dominate the politics of the capitalist class today. One is the ‘Singapore station’ which he casts as the logical conclusion of the politics of mainstream neoliberals like Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama. A second, ‘Budapest station’, represents the ultimate destination of right-wing populism like Donald Trump’s. The third, ‘Finland station’, is of course the main subject of his article and a reference to the Russian revolution and Vladimir Lenin’s historic train journey back from exile in early 1917.

Sunkara’s critique of neoliberalism in the Singapore station section makes important points, but also reveals limitations in his approach. While acknowledging its undemocratic character and relentless drive for neoliberal austerity, he portrays it as relatively benign and “not the worst of all possible endpoints”.

This dramatically understates the character of neoliberalism and the results of its worship of unrestrained capitalism: the vicious driving down of workers’ living standards in the name of profit, the loss of access to vital services like healthcare, the loss of millions of lives from wars over resources, the many and varied disasters of deregulation (like that recently at Grenfell Tower in London), and to neoliberalism’s complete inability to offer a future for youth and working people around the world.

It is precisely this model’s instability and brutality that opens the door to the Budapest station of right-wing populists like Trump – and authoritarian regimes in Hungary, Poland and elsewhere – in the desperate search of middle- and working-class people for some alternative to the dominant ‘Singapore’ route of capitalism.

Sunkara gets into what his own Finland station vision of socialism would look like. He explains that it would entail “worker-owned cooperatives, still competing in a regulated market; government services coordinated with the aid of citizen planning; and the provision of the basics necessary to live a good life (education, housing and healthcare) guaranteed as social rights. In other words, a world where people have the freedom to reach their potentials, whatever the circumstances of their birth”.

Without a doubt, such changes would represent a significant step forward despite being under threat of attack every time capitalism entered into one of its periodic crises. But this is not the same as the goal of socialism: a global, classless society which does away with capitalism’s organised apparatus of repression and replaces it with a new political order based on mass democratic organs of working people and the oppressed.

This has always been the destination called for by the socialist and Marxist movement. Many today, even on the left, may see this vision as hopelessly utopian. But, as Marx argued, it is the massive development of human productivity under capitalism which has laid the material basis to eradicate class division and oppression rooted in scarcity.

Marxism and the state

Sunkara states: “Stripped down to its essence, and returned to its roots, socialism is an ideology of radical democracy. In an era when liberties are under attack, it seeks to empower civil society to allow participation in the decisions that affect our lives”. Yet a central tenet of Marxism is that capitalist democracy is only a form of state rule. And Marx argues the dominant class in society is the one that controls the state apparatus. Marxists have long championed the most far-reaching, radical democracy. But Marxism has also explained that democracy does not exist in abstract. It must be understood in connection with the dominant economic system.

Under capitalism, democracy is always severely curtailed by the domination of the small propertied elite who use their power to prevent the majority from touching the foundations of their wealth and privilege. In other words, championing ‘radical democracy’ can only be done consistently if it is linked to ending the undemocratic rule of the capitalist class and transferring power into the hands of the working class and the oppressed.

Sunkara does not clarify this. In his ‘broad outline’ of a future socialism, which is dominant – market forces or the workers’ cooperatives? Sunkara states: “This social democracy would involve a commitment to a free civil society, especially for oppositional voices; the need for institutional checks and balances on power; and a vision of a transition to socialism that does not require a ‘year zero’ break with the present”.

However, if we are talking about ending the brutal and decaying capitalist system, how can this be done without having a fundamental, thoroughgoing break with the present order and its deeply undemocratic and repressive state apparatus? Instead, it appears that Sunkara is arguing against this when he says his vision of a transition to socialism does not require a ‘year zero’ break with the present.

It was this central point that Lenin argued for when he returned to Russia in 1917. Lenin stated that the feeble capitalists in Russia could not and would not deliver benefits for the working class. He called for the working class and poor peasants to break the power of the landlords and capitalists over society, and appeal to workers in other countries to follow this example and begin the construction of a socialist society based on workers’ democracy.

Fighting for reforms

As Marxists, we in Socialist Alternative fight for every gain that working people can win under capitalism. This can be seen in our leadership in the fight for $15, with Socialist Alternative member and Seattle city councilwoman Kshama Sawant leading Seattle to become the first major city to pass a $15 minimum wage. Two weeks ago, we helped make Minneapolis the first Midwest city to pass $15, this time under the leadership of socialist city council candidate, Ginger Jentzen. And just last week, Sawant and Seattle Socialist Alternative helped bring about another nationally important victory, this time a local measure to tax the rich to help fund affordable housing, education and other vital services.

In April, Kshama Sawant responded to questions in the Huffington Post about her views on socialism: “There are limits to reforming a system that is dominated by these massive and rapacious corporations. On the basis of capitalism, victories like raising the minimum wage are only temporary. Big business has many tools to make us pay for the crisis of their system. Again, a permanent and sustainable solution to all the problems facing working people is possible only by taking the biggest companies into democratic ownership, and reorganising the economy on a planned basis. Under such a system we could democratically decide how to allocate resources. We could rapidly transition away from fossil fuels, develop massive jobs programs to rebuild the country’s rotting infrastructure, and begin to build a whole new world based on meeting the needs of the majority, not the profits of a few”.

The issues raised by Sunkara about reform and revolution are not just abstract questions of historical interest. Which station we end up at today is intimately linked to how we assess the defeats and successes of the past.

After the second world war – an era of post-war reconstruction and huge economic growth, and under the enormous pressures of mass socialist and communist parties and radical labour struggles – important gains for working people were won in most western countries. But the tenuous economic landscape of today is radically different, with capitalism incapable of enjoying a sustained upswing, relentlessly attacking unions and working conditions, and demanding deep budget cuts in order to just maintain profitability and survive.

The new parties of the left can end up at a neoliberal Singapore station in the present, even as they look to the Finland station of the past, if they fail to draw the correct lessons. If left parties are elected to government without a definite program for an alternative to capitalism and a strategy to achieve it, they will inevitably be driven instead into attempting to manage capitalism. This can mean carrying out neoliberal austerity dressed up with kind words of compassion. Reform-minded, anti-austerity governments will ultimately be forced to choose between accepting the demands of big business or implementing radical and socialist measures.

As Rosa Luxemburg explained in 1900 in her pamphlet Reform or Revolution these two choices are not just ‘different roads’ to the same station. To be successful, the struggle for reform cannot be an end unto itself – serious reforms only come about as a by-product of serious social struggle. The capitalist class needs to be genuinely fearful of a wider revolt before it will grant major concessions like Medicare for all or a federal $15 minimum wage.

Further, if the struggle for reform is not used to develop the consciousness of working people and prepare the ground for a thoroughgoing socialist transformation of society, the capitalists will look to roll back the reforms which have been won, or to destroy those working-class forces which defend them. The ruling class will not hesitate to engage in economic war or even military coups against elected left governments. Left governments seeking to carry out their programs will run headlong into the brick wall of capitalist ownership and control of the key resources in society, as well as the capitalist state apparatus. This can be clearly seen in what happened to Syriza in Greece. To effectively fight against austerity in a time of capitalist crisis we need a Marxist program for fundamental change, and a plan to mobilise workers, young people and the poor to fight for it.

Bolshevism is not Stalinism

If genuine socialist ideas are to once again become the international rallying cry for a new society, we will have to seriously and honestly discuss the experience of the Russian revolution of 1917, the Bolsheviks, and Lenin.

The revolution shaped the entire political history of the last 100 years and represented a colossal effort to establish a new socialist world. Millions internationally were inspired to fight not just for a more ‘manageable’ version of capitalism but for a new socialist world based on solidarity, and without war and exploitation. Many of the gains and reforms working people won across the globe, including the eight-hour day, voting rights for women, free education, healthcare and a broad social safety net, came in the aftermath of the revolutionary wave unleashed by the Russian revolution.

The revolution was thoroughly democratic, with workers’, soldiers’ and peasant councils (soviets) built from below. The Bolsheviks went from being a small minority in the soviets to the leading force in the revolution through the course of 1917 by democratically winning over the masses of people to their program to defeat reaction, war and poverty.

Workers’ councils have been a feature of revolutionary struggles since the Paris Commune of 1871 and the first Russian revolution in 1905. Similar features developed in China 1925-27, the Spanish revolution 1931-37, France 1968, and Chile before the 1973 coup, just to name a few. We have seen similar examples of ‘revolutionary democracy’ in virtually every major upheaval centred on the working class across the globe.

Sunkara seems to be unaware of the democratic role of the soviets, while implying there was something fundamentally undemocratic about the Russian revolution. While appealing for a return to the Finland station, he insists that things will be different this time around: “This time, people get to vote. Well, debate and deliberate and then vote”. But the Bolsheviks did debate, deliberate and vote, quite often in fact. If they hadn’t done that, both internally and in the soviets, the October revolution would not have been successful.

The main argument of most of those who attack the Bolsheviks is that they supposedly wanted to centralise power and to eliminate all opposition. But this was not what happened in Russia in 1917 – in reality, the most democratic revolutionary upheaval that has ever taken place. It was after the Bolsheviks had come to power in October, with the overwhelming support of the soviets, that other political parties went over, one by one, to the side of the armed counter-revolution and helped plunge the country into civil war.

At the same time, 21 armies invaded the Soviet Union, including the US, Britain, France, and Japan. Alongside international solidarity, the only thing that allowed the Bolsheviks to survive the prolonged civil war, invasions, famine and destruction was the fact that they enjoyed the overwhelming support of the population who fought back against the murderous, pro-capitalist reaction.

How Stalinism developed

Leon Trotsky, who along with Lenin was a key leader of the Russian revolution, wrote that a “river of blood” separated the Bolsheviks from Stalinism. The Bolshevik party was arguably – and new historical research confirms this – the most democratic party of working people so far in history – and the most successful in leading the working class to power. Lenin and Trotsky perceived the revolution in Russia as a prelude to the European revolution and beyond. They understood that socialism could only be based on an international and voluntary federation of socialist countries, including the most economically developed. They understood that capitalism globally would fight back against a new workers’ state, and that one socialist country – particularly one as economically backward as Russia – could not survive on its own.

Stalinism did not arise from Bolshevism but from the isolation of the revolution in the young Soviet republic, famine, backward economic and cultural conditions, and the perishing of the most self-sacrificing worker leaders in the course of the civil war. The disappointment of the masses with the failures of the European revolutions was a key factor, especially in Germany 1918-23. These conditions allowed the rise of Stalinism as the Soviet officialdom increasingly controlled the use and distribution of scarce resources, thereby enabling themselves to become privileged.

A precondition for the rise of this privileged Stalinist bureaucracy was the destruction of the democratic traditions of Bolshevism, including the crushing of soviet democracy, mass repression of the Left Opposition, the extermination of virtually the entire Bolshevik Central Committee of 1917 and, ultimately, the assassination of Trotsky in 1940. The rise of Stalinism first undermined the planned economy by destroying the democracy necessary to its functioning, and eventually led to its destruction in what Trotsky explained as the bureaucracy ‘consuming’ the first workers’ state.

Not only did Leninism not usher in Stalinism, it took a bloody counter-revolution by the bureaucracy to reverse many of the democratic gains of the revolution and impede the worldwide struggle for socialism. The Communist parties around the world ceased to struggle for fundamental change, instead becoming props for Stalin and the needs of his bureaucracy, ideologically defended by his policy of ‘socialism in one country’.

Socialists will be confronted with questions about the Russian revolution and the totalitarian caricatures of ‘communism’. We need to have clear answers to these historical issues and effectively apply these lessons from 1917 to the workers’ movement today, which is operating in very different and rapidly-shifting conditions.

The continuing debate

Successfully translating mass opposition to austerity and the ills of the capitalist system into effective action against racism, sexism, war, poverty and joblessness, depends on adopting a bold fighting program, strategies and tactics. We must analyse a fast-moving situation to find the best proposals and slogans that can move people into action. This also requires workers developing their own mass independent party, democratically run, which can unite young people, the working class and poor to wage a determined struggle against the billionaire class.

History shows that ideas, program and leadership matter. Opportunities to challenge capitalism will only be fully successful if the ideas of Marxism can take hold in the working class with an organised socialist left. Socialists in the US, while starting from building a movement against the attacks of Trump and the Republicans in power, must also continue to engage in constructive debate about how to build the movement and political power for working people. Movements here will not happen in exactly the same way as in Greece the past few years or the Russian revolution 100 years ago, but there are important lessons to be learned from all these experiences.

Today the socialist movement faces dual tasks. We need to bring together socialist, progressive and fresh forces into broad and united action, struggle and resistance to defeat the right wing and the neoliberal offensive. But we also must seek to win the advanced layers of working people and youth to the understanding that a bold socialist program is the only way out of the crisis of capitalism, and of the need to build a revolutionary organisation capable of leading the fight to win such a program.

Crucial debates like this one around working-class history, international struggle, strategy and program must continue as we work together to defeat the billionaire class and rebuild a powerful socialist movement.