Peter Taaffe is a member of the Socialist Party (CWI in England & Wales).

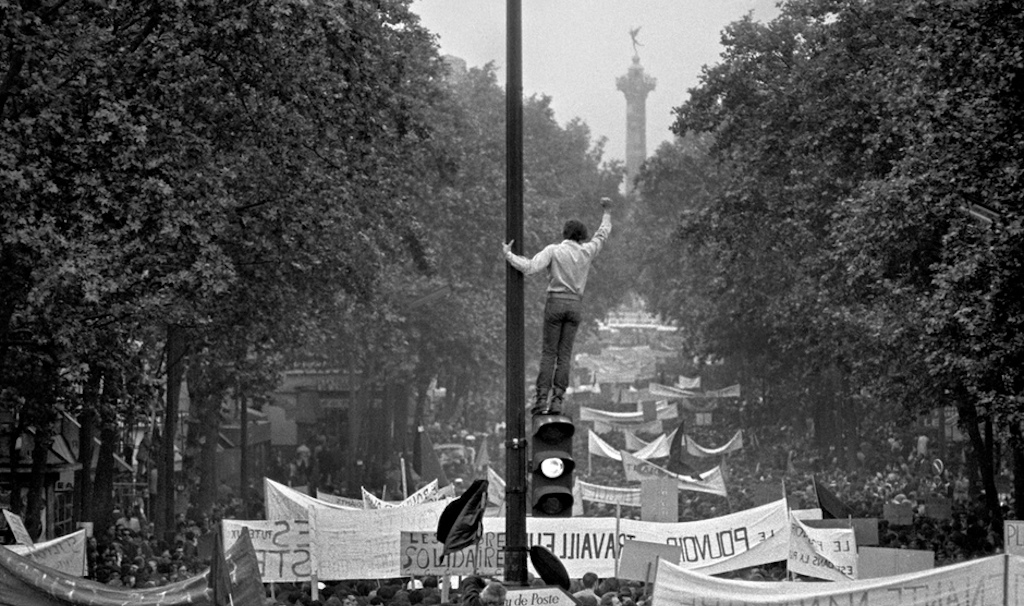

Factory and university occupations in France. US civil rights and rage at the Vietnam war. Upheavals in Italy, Pakistan and Northern Ireland. Revolt in Stalinist Czechoslovakia. Repression in Mexico. Events in 1968 sent shockwaves around the world. Some years stand out as historic turning points: 1789, 1848, 1871, 1917, 1968, 1989. Some, like 1989, signify a turning back of the wheel of history. Others are clearly identified with revolution. 1968 is of the latter. This was a tumultuous year when the floodtide of mass revolt swept over the narrow confines of capitalism and threatened the very foundations of the system. The high point was undoubtedly May-June 1968 in France, the greatest general strike in history, when ten million workers occupied their factories in a month of revolution. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels wrote of periods in history when decades appear like ‘one day’ in their apparent tranquillity and then there can be days in which the events of 20 years can be compressed. This was the case in one month in France in 1968. But it was not the only arena of colossal social upheaval, a year of revolution in fact and, to a lesser extent, counter-revolution throughout the world. Even to those who lived through and participated in these events, to merely recall their number and scale is breathtaking. Alongside France we also witnessed a mass movement in Mexico, drowned in blood in the infamous massacre of Tlatelolco Square. The official death toll was 300 but in reality was much more, possibly 1,000. This was also the year when the 10,000-day war in Vietnam changed decisively in the Tet offensive of the National Liberation Front, when the conviction of the inevitable defeat of the strongest military machine on the planet at the hands of ragged peasants took hold. On 4 February in Atlanta, in prophetic words, Martin Luther King declared: “I’d like somebody to mention that Martin Luther King junior tried to give his life to serving others”. He was murdered two months later. In March, Eugene McCarthy came within 230 votes of unseating the sitting president, Lyndon Johnson. Four days later Robert Kennedy announced that he would be entering the 1968 presidential race, only to suffer the same fate as Martin Luther King. In August, the privileged bureaucratic elite of the ‘Soviet Union’ deployed 200,000 Warsaw Pact troops to put an end to the ‘Prague spring’. A few days later, students were battered by mayor Daley’s ‘Democrat’ police in Chicago as they cried: “The whole world is watching.” And irony of ironies in this year of revolution, right-wing Republican candidate Richard Nixon was elected president after hypocritically promising to end the Vietnam war: “peace with honour.” Britain also witnessed growing opposition to the right-wing Labour government of Harold Wilson, both on domestic and foreign policy issues like Vietnam, with tens of thousands marching in Grosvenor Square against the war. Not only in the advanced industrial countries did turmoil prevail. In Indonesia, China (through the so-called ‘Cultural revolution’) and Pakistan, which in the movement of workers and peasants had a parallel with France, society seemed to be convulsed with waves of opposition reaching almost every corner. 1968 also signified the renaissance of culture – particularly affecting artists, musicians, students and the middle layers in society – but, more importantly, the re-emergence of the working class after the seeming torpor and social stability associated with the ‘rebirth’ of capitalism in the post-1945 period. It should never be forgotten that the revolutionary events of 1968 developed despite the 1950-75 world economic boom not having exhausted itself. Wages in the US had risen for most, 80% of the population had health insurance, and Johnson’s presidency had been compelled to introduce legislation such as the Civil Rights and Voting Rights acts. This, however, was only one side of the US boom because, as a result of the colossal increase in the cost of the Vietnam war, social welfare was cut back. Young people were in revolt while a million black Americans considered themselves revolutionaries. This underlines the Marxist analysis that revolutionary or pre-revolutionary situations are not the result of economic factors alone but can be ushered in by political events. The Vietnam war was acting to rot the economic and social foundations of US imperialism, the mightiest in the world, that could not pursue a policy of ‘guns and butter’. In the process, it destroyed Johnson’s presidency, dramatically demonstrating the advance of mass consciousness in 1968. Previously, the undoubted economic progress of substantial layers of the population, not just in the US but in Europe, Japan and elsewhere, led the capitalists to conclude that the social stability of their system was guaranteed, apart from a few leftovers from the past which could be dispensed with by skilful ‘social engineering’. Writing off the working class This was to miss the process of change taking place below the surface. They were not the only ones to sin on this score. Many Marxists had fallen into the trap of impressionism, concluding that the industrial working class was reconciled to capitalism, was to be written off or, at the very least, was quiescent and therefore ineffectual at that stage in the struggle against capitalism. The forerunners of the Socialist Party in Militant disputed this. We defended – and do still today – Marx’s emphasis on the role of the organised working class in the socialist revolution. This is the only class, organised and disciplined by large-scale production, that can develop the necessary social cohesion and combativity to carry through the tasks of the socialist revolution. This still holds true today, despite the deindustrialisation that has taken place in Britain and other advanced economies. The ‘new’ layers of the working class include, for instance, civil servants and teachers who, under the whip of neo-liberalism, have been driven into embracing methods of the working class like strikes. The peasantry, by its very nature, is divided into different strata, the upper levels tending to merge with the capitalists. On the other hand, the lower levels or small farmers are closer to the workers and, through economic ruin, tend to fall into the ranks of the working class. The same holds for the modern middle class, both in urban and rural areas. But many Marxists concluded prior to 1968 that the working class was conservative, some had been ‘bourgeoisified’ and therefore were no longer the main agents of social change. This led them to seek salvation elsewhere, with Marshal Tito in Yugoslavia, by implication recognised as an ‘unconscious Trotskyist’, Mao Zedong in China, or Fidel Castro. The latter had presided over a very popular revolution with elements of workers’ control but not with the workers’ democracy which existed in Russia at the time of the October revolution. The position of Militant at that stage collided with those like the adherents of the Trotskyist United Secretariat of the Fourth International (USFI). The leader of this organisation, Ernest Mandel, spoke in London in April 1968. We challenged Mandel’s thesis that so long as the US dollar remained stable, the situation in Europe would not fundamentally change for at least 20 years! The USFI and Mandel had concluded that the epicentre of the world revolution had shifted, at least for a time, to the former colonial and semi-colonial world. Militant always sought to explain the significance of events in this region of the world, involving as it did two thirds of humankind in the splendid movements of national liberation in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. Nevertheless, from a world point of view, the decisive forces for socialist change were still concentrated in the advanced industrial countries which would have to link up with the movements in the neo-colonial world. This did not at all imply that we thought that the world should wait until the workers of Europe, Japan and North America were ready to move. We gave full support, both in general and in action, to the national liberation struggle, even when it was under the leadership of bourgeois or pro-bourgeois forces, such as in Algeria at the time of the struggle against the French. But, as the experience of the Bolsheviks in Russia prior to the revolutions of 1905 and 1917 had demonstrated, in periods of seeming quiescence, it is vital to defend the role of the working class as the main agency of socialist change, even when that is not apparent on the surface. Intellectual shift and capitulation Most of these forces which claimed to be Marxist or Trotskyist were based primarily upon the radicalised students and intellectuals who had developed in the period up to 1968. The intelligentsia can play a key role in the development of the working-class movement, as the history of the Russian workers’ movement demonstrated. Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky, never mind Marx and Engels, evolved from the ranks of the bourgeoisie and petty bourgeoisie. However, they had broken, personally but above all politically, from the milieu from which they came. They generalised, summed up, the experience of the working class in the form of perspectives, programme, strategy and tactics, as well as organisation. They were sticklers for theoretical clarity, particularly on the issue of the social forces involved in revolution, the type of organisation needed by the working class, the laws of revolution and everything that flowed from this. They had nothing in common with those ‘intellectuals’, many of them ‘Marxists’, who could change their ideas like a man changing his clothes, as Honoré de Balzac put it. In fact, Marx and Engels, presently hailed even by bourgeois writers as ‘perceptive sociologists’, were invariably denounced in their time as ‘disruptive elements’, particularly by their ‘socialist’ opponents. Because they had a theoretical anchor, a method, they were inoculated against the episodic moods and fashionable theories which can complicate, to say the least, the struggle for clear understanding in the workers’ movement. Intellectuals are not an independent factor in history but reflect, sometimes in advance but very often in the rear, the movements taking place, sometimes subterraneously, at the base of society. Witness their baleful role following the collapse of Stalinism and the ideological campaign of the bourgeoisie for the ‘free market’. The overwhelming majority in the intellectual milieu of Europe and America, penetrating even into the neo-colonial world, either capitulated or accommodated themselves to a pro-capitalist position. Not just Francis Fukuyama but the overwhelming majority of intellectuals acquiesced to the idea that ‘ideology’, and therefore the class struggle, was dead. Even now, as we daily witness more and more masonry falling off the financial architecture of world capitalism, journals such as the London Review of Books carry articles that constantly refer to the ‘post-ideological age’ and a barely concealed contempt for the socialist project. Alain Badiou incredibly writes: “Marxism, the workers’ movement, mass democracy, Leninism, the party of the proletariat, the socialist state – all the inventions of the 20th century – are not really useful to us any more”. (The Communist Hypothesis, New Left Review, January-February 2008) Yet if there is one overriding conclusion from 1968 it is that the absence of a real mass ‘party of the proletariat’ allowed the French bourgeoisie to derail the revolution. Moreover, without the creation of such a force, favourable opportunities will be lost in the future. No doubt an eruption of mass working-class movements from below – which will take place as a consequence of the worst recession that impends since the great depression of the 1930s – will force this intellectual layer to adapt as they did in the past and many of them will jettison their present positions. Why France? A vital part of the process of the socialist revolution is preparation, ideologically, politically and organisationally. The outlook of most of the students and intellectuals who participated in the 1968 events was socialist in colouration; some were even Marxist or Trotskyist. This was because of the rumblings from below in the factories and workplaces and also because there was a ‘socialist’ model, at least in economic terms, in the planned economies of eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, albeit hobbled by bureaucratic, one-party totalitarian regimes. Nevertheless, the prevailing view of most of the organisations that based themselves upon the intellectual strata wrote off the working class, or any prospect of events like that of May-June 1968 occurring. They were not alone. On New Year’s Eve 1967, Charles de Gaulle, the 78-year-old president of France, stated: “I greet the year ’68 with serenity”. Reflecting the confidence of French capitalism, he continued: “It is impossible to see how France today could be paralysed by crisis as she has been in the past”. Sean O’Hagan comments: “Six months later, de Gaulle was fighting for his political life and the French capital was paralysed after weeks of student riots followed by a sudden general strike. France’s journey from ‘serenity’ to near-revolution in the first weeks of May is the defining event of ‘1968’, a year in which mass protests erupted across the globe, from Paris to Prague, Mexico City to Madrid, Chicago to London”. (Everyone to the Barricades, Observer, 20 January 2008) It was not an accident that France erupted into revolution, whereas neighbouring countries did not. If the fashionable theory at the time on the role of students as the ‘detonator’ was correct – of a conscious policy of confrontation with the bourgeois state to ignite working-class revolt – it would have developed first in Germany. There, the student movement was on the same or even a higher level than in France. The assassination in 1967 of Benno Ohnesorg, a student protester, by a police officer had produced a widespread student revolt and brought to prominence the Sozialistische Deutsche Studentenbund (Socialist German Students League). This was every bit as threatening as the movement that was to develop in France. However, the underlying social conditions were different. The whole preceding period under de Gaulle’s semi-dictatorial regime of the Fifth Republic had resulted in unbearable tension within the working class. France was a country where, as the tsarist intelligence service commented in 1917 on the eve of revolution, ‘an accidentally dropped match’ could ignite an explosion. This ingredient was provided by the brutal repression of the students which brought a million workers out in a general strike – reluctantly called by the trade union leaders. This led to workers going back and occupying the factories and to the revolution that ensued. It was specific features which placed France and the working class in the vanguard of the revolution at that stage. Because conditions were different in Germany and Britain – even in Italy which, in a sense, subsequently developed on a higher plane than France – the ‘spark’ of student revolt could not provoke the same reaction as in France. But if France had succeeded – and it could have done as the tremendous book by Clare Doyle, France 1968: Month of Revolution, demonstrates – then Berlin, Milan and Turin, even London, would have joined this movement. Italy’s hot autumn In Italy, for instance, Paul Ginsborg, a noted historian of that country, traced the effects of 1968 in the ‘hot autumn’ of 1969: “There followed the most extraordinary period of social ferment, the high season of collective action in the history of the Republic. During it, the organisation of Italian society was challenged at nearly every level. No single moment in Italy equalled in intensity and in revolutionary potential the events of May 1968 in France, but the protest movement in Italy was the most profound and long-lasting in Europe. It spread from the schools and universities into the factories, and then out again into society as a whole”. (A History of Contemporary Italy, Palgrave Macmillan 2003) A glimpse of the power of the working class has been given by Rossana Rossanda, one of the founding editors of the left-wing newspaper, Il Manifesto. She wrote of June 1969: “The paradox was that the Italian ‘hot autumn’ of 1969 was just beginning. Instead of starting up as usual after the holidays, factory after factory was being occupied by the workers, with the massive Fiat plant in the lead. Yet the Italian Communist Party (PCI) was entirely concentrated on our case [their impending expulsion from the PCI]. The hot autumn was the largest, most sophisticated industrial struggle since the war – not just a strike, but a matter of the workers taking the entire production process into their own hands, elbowing the management hierarchy aside. And these were not an experienced cohort, tested by decades of repression, but young workers, often without qualifications, whose education had come from the chaotic development of the society they had grown up in; who had taken something from the resounding student protests of the year before and made it their own. “Was it revolution the young workers had in mind when they marched in through the factory gates and took over the assembly lines? The decision ran like a spark from plant to plant: they fought to change their workplace, to keep it in their hands. They shook off the habit of obedience. When they spoke in the assemblies, the union leaders had to queue up for the microphone like the least skilled worker, just as at the Odéon in Paris the year before – but without that sense of atomization. They were in their own place; they talked about how things had been done up till now, what they could not take, how things could be done. The stakes were very high; for capital there could hardly be a greater challenge. The media knew it. At first they were pleased to see the PCI and the unions bypassed, then they were frightened”. (The Comrade in Milan, New Left Review, January-February 2008) These events struck terror into the Italian ruling class: “Symptomatic of the climate of the time was the confession, many years later, of one of the principal stockbrokers of the Milan Stock Exchange, Aldo Ravelli, a man not given to easy panic: ‘Those were the years in which – I am telling you to give you some idea of the atmosphere at that time – I tested how long it would take me to escape to Switzerland. I set out from my house in Varese and got to the frontier on foot’.” (Ginsborg, Italy and its Discontents 1980-2001, Palgrave Macmillan 2006) Ravelli never had to make the walk in earnest because the leaders of the mass working-class organisations in effect saved capitalism. But they were compelled to ride a tiger as almost a decade-long opposition from the masses developed within Italy. Mexico and My Lai massacres No less important was the effect in the neo-colonial world. The events in Mexico of October 1968 stand alongside France and Italy in the sharpness of the struggle. Although little commented on internationally at the time, they were the most bloody of the year. They were pushed into the background by the invasion of Czechoslovakia (the Czech Republic and Slovakia in one state under the iron heel of the Stalinist regime) just a few days before. Ed Vulliamy commented: “Historians write of the black gloves held aloft by medal-winning American runners at the Mexico Olympics. They write less about the white gloves worn by the Olympia Brigade of the Mexican army, tanks behind them and the helicopters aloft, which fired on students, families and workers in the Tlatelolco neighbourhood of Mexico City on 2 October, a week before the Games”. (True Voice of Revolution, Observer, 20 January 2008) Anticipating the bloody Argentinian junta of the 1970s, the Mexican ruling class resorted to the tactic of the ‘disappeared’ by dumping the bodies of the murdered at sea. So etched into the national psyche of the Mexican people are these events, it meant that “the revolution in 1968 would be more enduring there than anywhere else in the world”. Castro, however, kept silent, “failed to lift a finger in support of Mexico 1968 or any of its descendants”, partly because the Mexican bourgeois government was the only one to recognise the Cuban regime. More importantly, however, a new revolution in Mexico with the working class in the lead would have resonated powerfully within Cuba itself with demands for real workers’ democracy. Indeed, the participants stood for a ‘second Mexican revolution’, seeking to complete what the revolution of 1910, Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata had been unable to carry through. Not least concerned about what was happening was the US ruling class. It is always wary about the pivotal role of Mexico, both for its effect on the USA’s Latino population, but also as a gateway to Latin America. In 1968, the US ruling class had enough on its plate with the social convulsions set off by Vietnam. One reflection of this was that 3,250 young people went to prison on the grounds of conscientious objection to the war. An estimated quarter of a million others avoided the draft into the armed forces and one million committed draft offences. Yet only 25,000 were indicted. One study found the number of eligible Americans, who managed through student and occupational deferment and other factors to avoid military call-up, totalled 15 million. As a result, as historian Arthur Schlesinger junior wrote, “the war in Vietnam was being fought in the main by the sons of poor whites and blacks, whose parents did not have much influence in the community. The sons of influential people were all protected because they were in college”. (Michael Maclear, Vietnam: The Ten Thousand Day War, St Martin’s Press 1981) First place in the ranks of these ‘chicken hawks’ – those who avoided the draft but supported the war – were George W Bush and his ilk. Vietnam was the main motivating factor in provoking the movement of youth internationally in the period preceding 1968 but which broke out in mass proportions that year. The unspeakable violence meted out by the US ruling class by cowardly B-52 bombers and Agent Orange was typified by the massacre at My Lai that year, the horrific details of which were only revealed later. Two hundred unarmed Vietnamese civilians were officially accepted as being murdered but a US army author estimated that 700 were massacred. The punishment for the main instigator, Lieutenant William Calley, was three days in military prison. International scope The uprising of the youth in 1968 was indeed worldwide, not just in Paris or Berlin but in many countries. Indeed, the movement of the students in Italy was arguably the most important in seeking to link up with the working class, and nowhere else in Europe did they manage this so successfully. Some dismissed the actions of these young people as antics or, as the French sociologist Raymond Aron put it, ‘the play acting of spoilt rich kids’. Undoubtedly, for some who participated it was a case of ‘revolutionary measles’ from which they recovered before they were reintegrated into capitalist society. But others sincerely wished for a break from the deadening conformity of capitalist society and alienation that Marx spoke about. The idea that the producers were reduced to cogs in the vast machine of capitalism took hold even during an economic upswing, which fuelled the revolt of the youth. Many of these young people were, potentially, yeast for the rise of a new mass movement. In Italy, for instance, it has been estimated that there were 100,000 members of ‘far left’ organisations between 1968 and the end of the 1970s. This was a period of colossal experimentation, not just in politics but also in the arts, music and culture in general, which held out the prospect of liberation for the new generation that was impossible within the rigid confines of capitalism. There were ‘excesses’ in the movement, largely because of frustration, which in Italy flowed from the bureaucratic dead hand that the PCI sought to impose on the movement. But in the great swirl of ‘autonomous’ movements, groups and organisations were layers of young people who were looking for a clear road in order to change society. The PCI leadership, however, was looking towards an ‘historic compromise’ with the main party of the Italian bourgeoisie at that stage, the Christian Democrats. Coming up against this swirling, mostly positive movement from below, PCI dignitaries mobilised to crush autonomous movements in the universities, sometimes using ‘muscular workers’ to defeat the students. This, in turn, led to ultra-left gestures, some of them extremely harmful to the struggle for socialism and liberation – for instance, the development of terroristic ideas in the ‘Red Brigades’ and other armed groups. A generation was tragically lost to struggle who could have regenerated the Italian workers’ movement on a much higher plane, through the development of a mass, or at least large, alternative party to the PCI on clear revolutionary, socialist and democratic lines. The movement in eastern Europe, to some extent, mirrored that in the west. This was presaged by the Prague spring, the ejection of Stalinist hardliners from the leadership of the Czechoslovak ‘Communist’ Party. The replacement of the Stalinist creature, Antonin Novotný, by Alexander Dubček did not mean, however, a switch to workers’ democracy, as was presented even by some Marxists at the time. Dubček’s ‘socialism with a human face’, which received mass support in Czechoslovakia and beyond, did not represent a real step in this direction. It is true that the loosening of the reins of Stalinism led to huge political ferment in which the ideas of workers’ democracy, many of Trotsky’s ideas, demands for a free press, democratic control and management of industry, were thrown up and debated. But Dubček represented the process of bureaucratic reform from the top to prevent revolution from below. This could not be tolerated by Moscow’s Stalinist bureaucracy. In Poland in 1956 it had been compelled to accept Władysław Gomulka coming to power. Gomulka, like Dubček, represented a more liberal and nationalist bureaucratic regime. At that stage, Moscow had its hands full with the Hungarian revolution, with its ideas of real workers’ democracy, which represented a mortal threat to the Stalinist regimes. But Czechoslovakia in 1968 was developing against a profoundly changed world situation. To allow Dubček to persevere would have opened the floodgates in all the states of eastern Europe that were seething under the stranglehold of Stalinism. The crushing of the Prague spring was therefore deemed unavoidable by Russian leader, Leonid Brezhnev, and was acceded to even by Castro, who weighed in after some delay in support of the Russian tanks in Prague. This laid the basis for the mass disillusionment with Stalinism and a blow to the idea of a planned economy upon which it rested, not just in Czechoslovakia but throughout eastern Europe. As subsequent events in Poland showed, it also fuelled support for the idea of a return to capitalism. 1968 therefore had an international scope, in the same way as 1848 and 1917. The ruling powers today wish to banish the spectre of 1968. First place among these, appropriately, is the French bourgeoisie, represented by the words of Nicolas Sarkozy. He boasted during his presidential campaign in 2007 that his victory would banish the ghosts of 1968: “May ’68 imposed intellectual and moral relativism on us all…” he declared. “The heirs of May ’68 imposed the idea that there was no longer any difference between good and evil, truth, falsehood, beauty and ugliness. This heritage of May ’68 introduced cynicism into society and politics”. Incredibly, he even claimed that 1968 helped “weaken the morality of capitalists, to prepare the grounds for the unscrupulous capitalism of golden parachutes and rogue bosses”. (CounterPunch, 4 June 2007) No, these are the endemic features of capitalism which the generation of 1968, both then and subsequently, have tried to eradicate by preparing the ground for the completion of 1968, the socialist transformation of society. The French bourgeoisie inveighed against the French revolution, the heroic Communards of 1871, the sit-down strikes of 1936, as they did and do today against 1968. As with those previous events, they will not succeed in extirpating the example of this, the great year of revolution and near-revolution. It is the task of socialists to keep the traditions of 1968 alive but also to learn from the deficiencies of this movement, in order to prepare the socialist future for humankind.