Rob Jones is a member of Sotsialisticheskaya Alternativa (CWI in Russia).

In 2003 the imperialist powers launched a brutal ‘shock and awe’ campaign intended to remove Saddam Hussein and establish a new democratic order in the Middle East. At least that was the official cover, in reality it was as much an attempt by western imperialism to get its hands on Iraqi oil. It has been a disaster, with over a million killed in Iraq alone. Since then the country and its neighbours have been engulfed by war, unstable governments and grinding poverty.

Since the eventual withdrawal of US troops in 2011, although some have since returned, Iraq has faced many protests, including its own version of the Arab spring. But now, against the background of mass uprisings across the world, including again in Egypt, Lebanon and now Iran, the country, and the government have been shaken to their very foundations by a predominantly youthful, working class mass movement. Even though at the end of November the Prime Minister Adel Abdel Mahdi was forced to resign, protests continue.

As is the nature of any tinder-box, any spark can set it off. And there have been many. It now seems a long time ago, but in late September the security forces used water cannons to disperse a demonstration of high school graduates outside the Prime Minister’s office demanding work. For three days after that, solidarity demonstrations spread across the country.

Just days later, a new wave of protest followed the announcement by the Prime Minister, who is seen by many as being close to the Iranian regime, that Lieutenant General Abdel-Wahab Al-Saedi was being transferred from the Counter Terrorism Force to the Ministry of Defence. Al-Saedi, who had commanded the battle against IS in Mosul had earned a reputation as a “national hero” and his demotion was seen, particularly in the social media, as a result of Iranian pressure on the Iraqi government. Discontent on this issue only subsided when Al-Saedi himself accepted his demotion and the issue was soon forgotten.

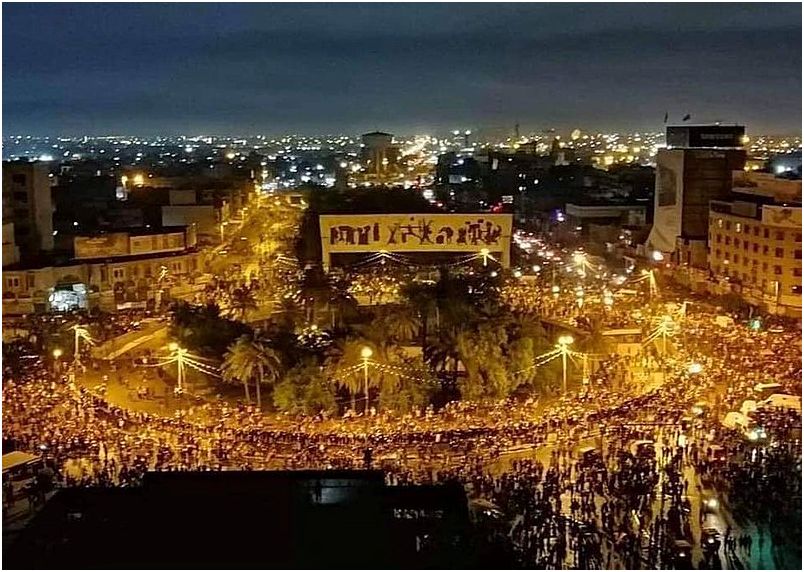

On 1st October over a thousand youth flooded Tahrir Square in Baghdad in a peaceful protest against unemployment – already the biggest protest against Adel Abdel Mahdi since his appointment. As they were chanting anti-government slogans they were met by the riot police, firing live ammunition. These youth set the tone for future protests. Fadhel Saber, an unemployed 21 year-old explained that “We want this government changed. This is a government of political parties and militias”.

Despite the attempts by the government to limit the spread of the protests by restricting the use of the internet and announcing a curfew in a number of cities, within a day they had spread across the country from Baghdad to Nasiraya in the South where it was reported that police had “lost control”, as well as Amara and Hilla. “We want jobs and public services. We’ve been demanding them for years and the government has never responded”. Facebook and twitter helped the protests spread to the Eastern city of Kut, where protesters tried to break into the local government building. Thousands laid siege to the administration building in oil-rich Basra and there were peaceful protests in the north – in Kirkuk and Tikrit. Even a statement issued by the Prime Minister that evening promising jobs for unemployed graduates did not calm the situation.

A report recently written for the World Bank recently put youth unemployment at 36%. Despite the fact that Iraq is one of the world’s largest oil producers, 40 million people live on less than 5 euros a day while millions lack access to adequate healthcare, education, clean water and electricity.

The toll of dead and injured grew quickly – by the end of the first week over 100 had been killed and thousands wounded. Baghdad remained under curfew. Imram Khan, a reporter for AlJazeera described the situation in Baghdad on 5th October: “The protesters are more determined than ever. The more people died, the more they would come out onto the streets. What began as a demand for jobs and opportunities mutated into anger at Iraq’s security forces. The same security forces that defeated ISIL have turned their guns on unarmed protesters. That has spurred the protesters to ask why they are being targeted. They are not ISIL. They are Iraqis… It is not this government that they are angry at. Past governments are also at fault. The protesters do not want a change of government. They want a change of governance. As one Iraqi friend put it to me: “Same attitudes but different faces in our government are the problem. The system needs to change. Our politicians need to build a country, not build their own profile.”

After a short interlude, protests resumed towards the end of October. Tahrir square has since been permanently occupied with many camping out in the “Turkish restaurant” – a high rise building devastated during the war. Self-organisation became the norm with people providing security to try and keep provocateurs out. Tuk-Tuk drivers (small two wheeled vehicles) transport the injured, doctors and medical supplies around the square. A group of youth, known as “goalies” have set themselves the task of intercepting tear-gas grenades that are being lobbed into the square by the militias and security forces.

Significantly, a large number of women are participating: “we are a group of girls, and we went down to the streets under the slogan ” I am the revolution ” to reflect the reality of the protests, and show the world that Iraqi women in general and Basra women in particular will not leave the protests since October 25th and women will remain until all government is dropped” The square is daubed with slogans warning against sexual harassment, while women who are demonstrating for their rights at the same time take part in security patrols and medical teams.

Again protests spread across Central, South and East Iraq. In many cities, protesters were attacked and shot at. To date over 420 people have been killed and almost 20,000 wounded. Demonstrators have turned their anger on local government buildings and often Iranian consulates. Although these regions are mainly Shia, it is significant that the protesters all present themselves as united – Tahrir square resounds with the chant “Not Shia, not Sunni, not Christian. We’re all one Iraq.”

One region that has remained relatively untouched by the protests is the semi-autonomous Kurdish region in Northern Iraq. This is not to say that the region does not experience similar problems, indeed there have been serious protests over the same issues in recent years against their own ruling elites centred around the two richest families – the Barzanis and the Kurdistan Democratic Party and the Talabanis with the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan. In part however, concessions made by the Federal government under Mahdi, including the release of promised funds to pay civil servant wages have to a small degree eased some of the problems, although many in the region sympathise with the protests. More significantly, however, has been the position of the Kurdish regional government, with the apparent support of the communist party to do everything to prevent protests for fear the region will lose its autonomy if the calls of the Baghdad protesters for the “de-sectarianisation” of Iraqi politics are implemented.

In the same way, the Sunni population particularly in towns like Mosul is not as visibly involved. There is clear support particularly from the Sunni youth in mixed areas and on social networks, but there is a fear in Mosul that any open demonstrations will be portrayed as IS activity and meet vicious repression.

What however is clear, irrespective of the ethnic or religious background, these protests have erupted in the impoverished working class areas and slums, amongst the young who bear the brunt of poverty. Since the end of October the mass protests have taken on a new, a more mature character. In part this is due to the decision of the unions of teachers and lawyers to take an active part. Many schools and universities shut down as students went on strike. One commentator described how: “Young girls in school uniform and rucksacks were seen trekking through streets littered with tear gas canisters”.

Other trade unions have, unfortunately, played less of a role in the protests. In part this is due to the position of the Iraqi Communist Party which sees no real need to participate as well as the weakened position of the unions due to the past years of war and sectarian conflict. At the end of October, the Conference of Iraqi Federations and Workers Unions, an alliance of national centres, issued a statement in support of the protests and calling on its members to participate. Although many individual members, including oil workers have participated in protests, no organised strike call has been made. Without their intervention, a month and a half into the protests, it was left to the teachers’ union to call a general strike which gripped schools, government offices and in some areas, shops and markets.

In one sense, this weakness has meant that the protestors have lacked the economic leverage to force the government to back down – after all teachers and lawyers do not directly provide the wealth in society. But other ways of affecting the economy have been found. Demonstrators have blocked roads around the major cities and bridges but most significantly have blockaded the Umm Qasr commodities port near Basra, cutting trade by 50% and costing $6 billion a week.

A few days later, Khor al-Zubair, Iraq’s second largest port was cut off, halting trade activity as oil tankers and other trucks carrying goods were unable to enter or exit. Near Basra too, work at the state owned Nassiriya oil refinery was disrupted as the oil tankers were blocked from the roads. This raises the perspective that if the protesters made an open call to workers in industry to stop work, or even better if the trade unions were to do so the movement would be much more powerful.

The escalation of the protests in this way forced the ruling elite to look for a way out. Leading Shia cleric Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani set the ball rolling for calls for the government to resolve the crisis – soon tribal leaders met with Mahdi too, asking him to move aside. When the news of this reached the square, it was met with cries of “traitors”. The problem faced by the ruling elite is that the resignation of Mahdi alone was not enough to satisfy the masses. As one protester commented: “We’re here to bring down the whole government, to weed them all out! We don’t want a single one of them. Not Halbousi (Speaker), not Abdul Mahdi. We want to bring down the regime”.

Only after weeks of protest the Iraq Communist Party withdrew from Parliament whilst leader of the largest parliamentary party Shia Muslim leader Muqtada al-Sadr, who had been elected last year in a block with the communists, appealed to his political rival Hadi al-Amiri to help remove Mahdi.

By the beginning of December demands against the government became much more specific. After Mahdi’s resignation, protesters were chanting “”No to Muhasasa, no to political sectarianism”. This theme was reflected on the white banners and even in the anti-sectarian poetry being read out in the squares. This demand is an indication of how deep the crisis is in Iraq and actually a confirmation, that unless there is revolutionary change, the demands of the protesters cannot be met.

The initial plans to introduce ‘Muhasasa’ were drawn up by the various opposition groups in the early 1990’s as they were planning how to replace Hussain’s regime. It envisaged the division of power on a quota basis for public office and political positions, as well of course the division of state resources between the different religious/ethnic groups. This plan was then adopted by the US occupation as the “Iraq Governing Council”.

Protesters complain that the very system not only enshrines ethnic division but was, to a large degree, responsible for the sectarian civil war. Although the war has died down, in elections Shias and Sunnis are often motivated by the fear that if they do not vote, the other side will dominate. Even worse, the whole system relies on cronyism, parties make no pretence of representing ordinary people, instead use the system for their own party interest. They become easy prey for the different imperialist forces trying to build influence in the country. And this leads to inherent corruption as Ali Khraybit, a filmmaker comments from his tent on Tahrir Square: “Each political party has control over a group of ministries where it hires its own entourage. The system provides a legal cover for abusing the system.”

The traditional “left” party , the Iraq Communist Party, bears a large degree of responsibility for this situation – which is why its influence in these protests is minimal. Only well into the protests, the ICP called for the replacement of the government by technocrats and independents and of the current system by a ‘new one’. The problem it faces are two-fold. Firstly, it itself is part of the system, having taking part in the Sairon coalition, headed by the Shia cleric Muqtada al-Sadr which gained the highest vote in last year’s general election.

Sadr, whose base is amongst the poorer Shia population gained some prominence during the February 2016 mass protests in Iraq but is now associated by many as also responsible for the problem as his party participates in Mahdi’s government. His attempts to intervene in the current protests are met with indifference at this stage. The ICP’s justification for this approach is that “Iraq is still in a stage of ‘capitalist development’” that requires a mixed economy, a ‘social market’ and the promotion of trade unions and social security. The more left wing “Workers Communist Party of Iraq” appears to address its agitation at ending Islamic influence rather than offering any socialist solution.

A very impressive feature of the movement has been the way in which protesters are rejecting foreign interference in Iraq. The anger is directed against “Muhasasa” left in the aftermath of the American occupation which many blame for the sectarian conflicts. The basis does not really exist for a turn towards US imperialism as it does in some other countries, because the Iraqi masses already understand what US intervention brings with it.

There is huge anger however being turned against Iranian influence in the country. Not only is Iran seen as a major beneficiary of the ‘Muhasasa’ system, Iran is a major sponsor of Mahdi’s government and was putting much pressure on individuals such as Sadr not to push for his downfall. Throughout the protests Head of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards, General Soleimani has been a regular visitor to Iraq, insisting on tough measures to put down the protests. Many protesters blame Iran for setting up the paramilitary militias that have been attacking them across the country. This is why so much anger has been directed against Iranian property in different cities.

Some commentators, undoubtedly relying on the narrative of the western media, have seen this and fallen into a trap of claiming that “nationalist chants are common among the protesters, with many wrapped in the Iraqi flag”. They completely misunderstand the driving force behind these protests. Not only do the protesters consistently insist that they represent all ethnic groups, when protests broke out recently in Iran, a message was sent from Tahrir square saying: “”It is crucial for us that you should be aware of the fact that we Iraqi People only have a genuine love for you. Our problem is with the Iranian sectarian regime, which backs all the corrupt politicians, criminals, and murderers in our current government”.

Far from trying to unite all people in Iraq (or into one of the ethnic groups) against other nations or ethnic groups as nationalists would do, the protesters are trying to do the opposite. They are uniting working people and poor of all ethnic groups against their own undemocratic and corrupt national elites. Although written for a different epoch, the comment of Leon Trotsky “The awakening of the oppressed and dismembered nations, their struggle to unite their severed parts and to throw off the foreign yoke, would have been impossible without a struggle for political liberty” could almost have been written to describe Iraq today. “We want a country” is the cry of some of the youth now on Iraq’s streets.

At the time of writing, Mahdi has stood down but still continues as interim leader. Protesters met his resignation with singing and dancing, but they are still angry – his resignation is not enough. They don’t want any other political leader to take over. They want an end to the whole system. As one put it: “If they agree to hold early elections, the same faces will return … They’ll just be reshuffled”.

One bourgeois commentator, Fanar Haddad, argues that “Today, the political sphere in Iraq is more of a diffuse web of vested interests (formal and informal, Iraqi and foreign) than ‘a regime’. Going against it is less like butting against an immovable rock and more like punching through jelly. Paradoxically, this might be one of its most powerful attributes and one which could ensure its survival. It precludes the possibility of state capture without its complete destruction by way of a major civil war or a foreign 2003-esque intervention”.

To some degree, of course, he is correct. The ‘Muhasasa’ system has been created by the Iraqi bourgeois, hand in hand with US and Iranian imperialism precisely to ensure that the vested interests of the different sections of the Iraqi ruling elite are protected, not just from each other, but most importantly from the working masses. The protesters are absolutely correct to say that the resignation of Mahdi will not make any fundamental difference. If the system has to be changed, the question is by whom? The protesters are correct to have no confidence in today’s political parties, they shouldn’t be allowed to redesign the system.

The only alternative is for the protesting masses to establish elected committees, representing those participating in the protests, in the schools and universities, of workers in the ports and oil sites and from the working class regions and to convene a constituent assembly to decide in a democratic fashion how Iraq will now be governed in the interests of the working people, youth and students.

The demonstrators have a healthy and fully understandable contempt for the political parties and militias who have caused nothing but conflict, corruption and poverty over the past years. There should be no confidence given to any of them. But there is one group that does not have a party representing its interests – the working class. Parties such as the Iraq Communist Party is no more than a caricature of a working class party. A revolutionary socialist party is needed that will organise to overthrow capitalism – to start by nationalising the oil industry and other key industries under workers’ control and management so that the wealth of Iraq can be used to pay decent wages, support education and healthcare, and build proper homes.

“Not Shia, not Sunni, not Christian. We’re all one Iraq” and “We want our country back” are demands that demonstrate a real understanding of the need to end sectarian conflict and fight to take power away from the ruling elites and stand against the imperialist powers, whether US, Saudi, Iran or others, and their attempts to control and exploit the resources of Iraq. In building a new Iraq however, there should be no compulsion of nationalities or religious groups. In a genuinely democratic Iraq the right of self-determination, not based on the greed of the different ruling elites but in the interests of the working masses would allow the different groups to live in harmony.

Iraq has suffered for decades from capitalism and imperialism – its natural resources have been robbed by the ruling elite and the masses are left without jobs, decent homes and enough money to live on. The socialist transformation is needed so that power is in the hands of the working class and its allies, so that the wealth of the country is used for the benefit of all with a democratically planned economy. A socialist Iraq would be an incredible example of how sectarian conflict and poverty could be ended for the whole Middle East, leading to a democratic socialist federation of the Middle East.