Amy Ferguson is a member of the Socialist Party (ISA in Northern Ireland).

Tragic Consequence of Missed Opportunity for Socialist Change

May 3 is 100 years since Ireland was partitioned under the “Government of Ireland Act” to leave the largely Catholic Republic of Ireland as an independent state and Northern Ireland with its part Protestant, part Catholic population still linked to Britain.

Some say that the partition of Ireland a century ago was inevitable, a “natural” reflection of the sectarian division on the island. Others argue that an independent, united – and capitalist – Ireland was within reach, if only individuals like Michael Collins, leader of the Irish Republicans, had stayed the course. Neither of these narratives is accurate.

The Communist Manifesto states, “The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.” What this argues is that class struggle has been the ultimate determining factor for all major events since the dawn of class society — this is also true in the case of partition.

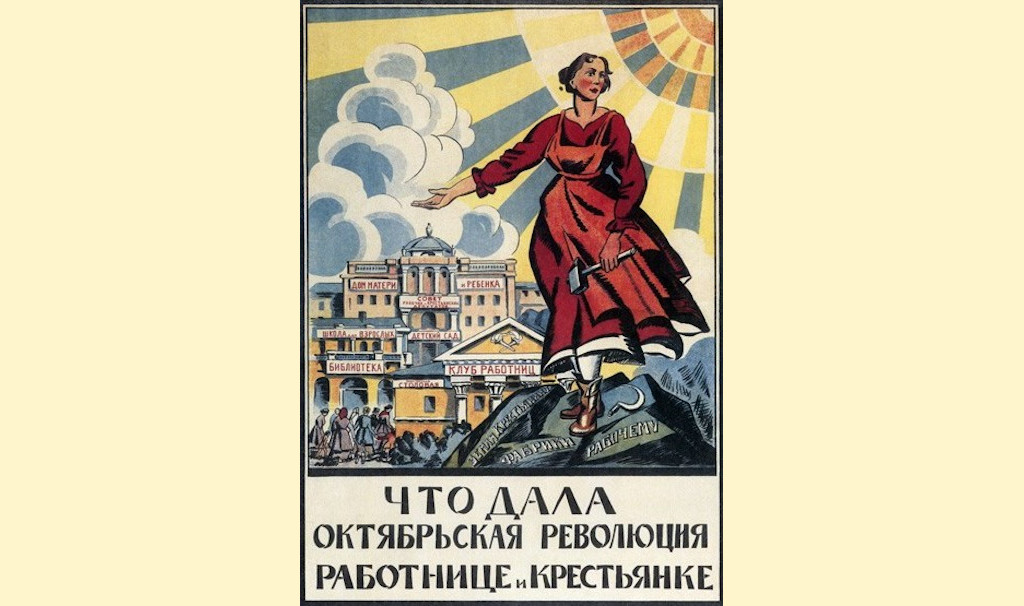

In the early 1900s, class struggle was rapidly accelerating across the globe. This was the case in Ireland too. In 1906, there were strike waves of women workers for a pay rise across Ireland. There was the Dublin lockout of 1913, land seizures, ‘soviets’ established in various areas, and workers’ occupations up and down the country. Moreover, the ITGWU (the union of the socialist revolutionaries James Connolly and Jim Larkin) grew from 5,000 members in 1916, to over 120,000 in 1921.

Workers’ unity in the north

In the north, there were significant examples of workers’ unity and militancy which sent shivers up the spine of the capitalist class. The 1907 Belfast dockers’ and carters’ strike saw the Protestant and Catholic working class unite to fight for better working conditions. The strike itself involved about 1,000 workers but, at its peak, 100,000 from across the sectarian divide marched to City Hall.

Then, in 1919, there was a battle for a 44-hour work week. Again, this struggle brought Catholics and Protestants together in their common class interests — the bosses’ divide-and-rule narrative was pushed back. For instance, at the beginning of the dispute, there were a few sectarian incidents, but the workers reacted quickly and set up a body of 2,000 to patrol the city and keep it free of intimidation.

The lasting legacy of these battles demonstrates, firstly, that sectarianism is not a constant theme in our history and secondly, that capitalists fear nothing more than workers’ unity.

Divide and rule

All these things combined, north and south, represented a movement with revolutionary potential. This was the actual state of Ireland when the British ruling class decided to play the card of partition. They were terrified for the future of their exploitative system and Empire.

If workers were so determined, how did the British ruling class end up successful in their game of divide-and-rule? Often, the missing ingredient in class battles that prevents workers from achieving that final goal of ending exploitation for good is the question of leadership.

Labour must wait

As well as organising industrially, workers increasingly looked to Labour for a political voice. However, the reformist heads of the movement failed to provide leadership which could bring together the working class around a common program for both national and social liberation. Instead, they bent the knee to the nationalist Sinn Féin, following de Valera’s demand that “Labour must wait” – that the so-called “concerns of the nation” had to come before those of any class within it, or – more accurately – that the interests of the working class must be quashed in favour of the interests of the wealthy business and land owners.

The pro-capitalist and ultimately sectarian nationalism of Sinn Féin could have no appeal for Protestant workers in the north, who feared the economic impact of independence on a capitalist basis, but also the potential to become an isolated and oppressed minority. This allowed the British establishment and sectarian forces to reassert control and drive a wedge between workers, in order to save their system, ultimately leading to partition and the establishment of two oppressive and sectarian states on the island.

Lessons for today

Partition was not inevitable. The dominant trend had been towards working-class unity, militancy and support for socialist change. The capitalists wanted to divide workers in an effort to save their system. This was made possible due to the treacherous approach of the labour leaders, who ignored the demands of the working class and instead effectively propped up capitalism. We still live with the legacy of that defeat today. We must learn the lessons of the missed opportunity posed in this period, in order to inform the struggle for socialism today.

Want to read more?

Divide & Rule: Labour & the Partition of Ireland

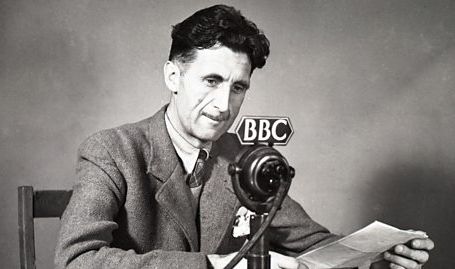

Written by Peter Hadden 40 years ago, Divide & Rule is a socialist classic, which argues that the partition of Ireland was a conscious act of the British ruling class in order to cut across a working-class movement with revolutionary potential. Importantly, it argues that this was not inevitable but that, with a socialist program and leadership, a united movement of workers had the capacity to cut across sectarian division and challenge imperialism and capitalism itself.

“The tactics of ‘divide and rule’ of setting Catholic against Protestant, has again and again been used in Ireland. But history shows, not once but repeatedly, that the oppressed masses are capable of overcoming religious divisions and withstanding the attempts of the exploiters to set them apart. Unity of the oppressed has always been possible on the basis of opposition to oppression.”

The 2020 edition, with a brand new introduction, was printed as we approach the centenary of the partition, so workers and young people can draw the lessons of this historic period and apply them to the struggle for socialism today.

Printed copy including postage within Ireland — €7

For postage outside Ireland, email us at [email protected]