This article is based on interviews with current and former Amazon warehouse employees.

6:30 pm: time to wake up.

You’re a little peeved because your housemates have been noisy since they got home from work a half-hour ago, even though you’ve asked them time and again to keep it down just for that little bit between them returning and your leaving to your job as a picker at the Amazon fulfillment centre. But this is the only place around with rent you can afford, so the crowdedness and noise are just something you have to accept.

My back feels worse than yesterday, you think as you roll out of bed. I’m 24, I didn’t think it would start this soon. Your knees feel it too, as your feet hit the floor. The shower doesn’t make you feel much better, but maybe you’ll get lucky and there’ll be a free seat on the bus today. You nod to your roommates as you grab a banana from the kitchen, then you’re out the door.

You’ve got to run the last couple of blocks to make the bus – this walk to the stop always takes longer than you think it should. Gotta make sure you’re there by 8:15 on the dot for the nightly shift kick-off.

You get a seat and are thankful that you can doze off for a few moments on your 45-minute trip. After a few stops you’re joined by your coworker.

“All set for another night of hell?”

“As long as Mark keeps out of my hair. How’d a guy like that ever get to be a manager?”

“Probably because he was even worse at everything else.”

“Maybe he’s Bezos’s nephew or something.”

It’s nice to like your coworkers.

The bus gets you there in time, this time. You do have to wait around to sign in – you also can’t get there too early – but it’s better than the alternative. Last week your bus got caught up in road construction and both of you got “pointed” (it would be called “written up” anywhere else). You were almost over your 60-day hump since you got hired to get your blue badge (and a 50-cent raise), and that one late day sent you back to square one.

Mark is leading the nightly stretching/pump-up session. The “rah-rah” type stuff is lower-key than before the virus, you’re told, but still it gets on your nerves as you try to sway the soreness out of your spine. Lots of your fellow night-shifters are trying to work their strains and aches out too. Hopefully, no one gets a bad knock today.

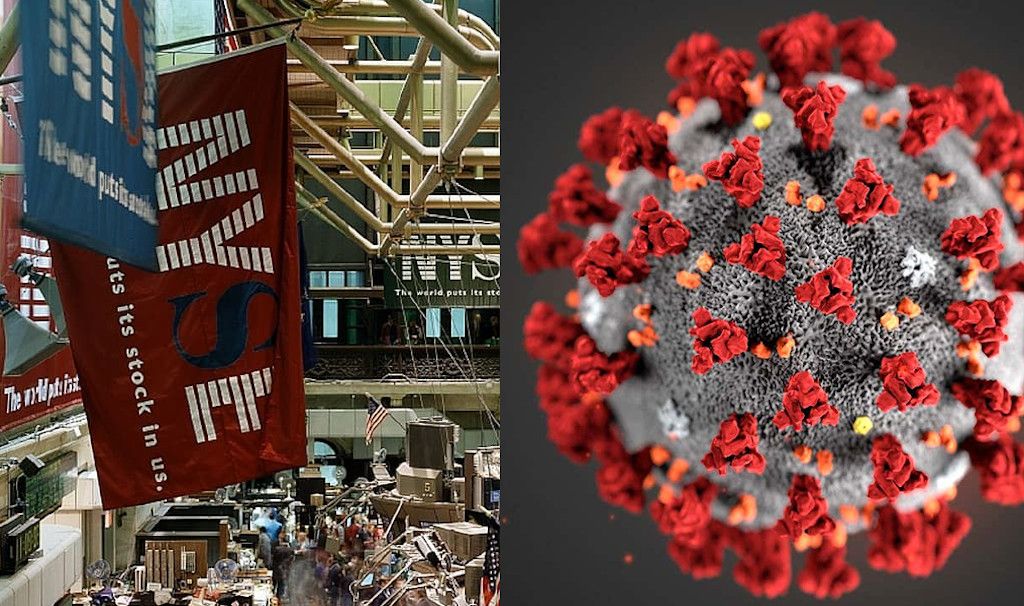

When Mark finishes with “Any questions?” you’d like to ask why the pandemic “hero pay” and double overtime pay was ended even though COVID-19 is certainly still spreading. You’d also like to ask why you never even got that pay yourself, just because you were hired a couple of weeks after the pandemic officially began and didn’t even know about it until you heard a couple of other pickers talking about it in the lunch room.

But you’re pretty sure that isn’t the sort of question Mark is interested in hearing.

The start of your 10½ hour shift is here, and you check your badge to see where to go today. Ugh, great. You’re picking in Section G to start. That’s the part of the warehouse where the exterminators never quite seem to make a dent. You know that the rat droppings usually do get cleaned on the lower levels… guess you’ll just have to be extra careful when you’re getting stuff from high up. At least you’ve got gloves and a mask these days.

No time to dally on those kinds of thoughts though, because the clock is ticking. It’s time to get reacquainted with your closest pal for your shift: your scanner gun. You’ll be getting directions from that thing and scanning at least 50 packages per hour with it, so you’d better make sure to treat it well. Better also make sure you don’t fall below 50 per hour, because you know that they give talkings-to to the slowpokes, and you also know that’s the last you ever see of some of them. And it’s not like there are a ton of jobs up for grabs these days.

Up in the cage you go. Heck of a name for a little motorized moveable platform, really. You’d figured, when you were applying for this job, that a company as huge and wealthy as Amazon would have state-of-the-art lifts to get up to those high, high shelves. These ones could best be described as “rickety.” That can’t be good for your knees when you’re way up there, or your nerves.

But up you go, scanner at the ready. Beep. Beep. Move the cage a little farther along. Beep. You used to kind of like this. You thought about how you felt useful, helping to get all these boxes from A to B. People need clothes, and microwaves, and toilet paper (especially when you started), and all the other stuff that passed through your own two hands. But even after just a couple of weeks, as the pace wore you down, as one stack of boxes seemed to merge into the next and into the next, as you read the news articles of the guy at the top buying yet another mansion… the charm disappeared pretty quickly.

Damn. Gotta pee. You skipped coffee before work just so that you could be sure to have the best chance to avoid a bathroom break before your meal break. The company really doesn’t like too many trips to the can. Even before you thought about working here, you knew of those stories in the media of Amazon timing bathroom breaks down to the second. Allllll the way across the warehouse floor, try not to get run over, hope no one gets mad at you for leaving your junk in their way, thank goodness there’s no line-up, do your business quick, back out to the floor. Wasn’t too long that time – no one should mind that.

Masses of musky cardboard and a zillion yellow plastic bins later, it’s time for food – 35 whole minutes, five minutes longer than before the pandemic! You and your bus-riding pal sit with a couple of others. The lunchroom has always felt a little empty; they’ve got workers taking their breaks in staggered schedules now.

“Did you get a look at the new hires they brought through today? Only seven, maybe things are going to slow down soon.”

“I wonder how many of them will still be around next week?”

You wonder how long you’ll be around, and whether it would be scarier to have to leave here after a week or five years. The ones who have been around for that long are few, and they look dead-eyed.

You can’t wonder for long. Back to work: 6:45 a.m. is still a long way off. And it’s more of the same. Up in the cage, wobble wobble, beep beep. Fill up a cage, drop it off, move to a new one. A few fragile things: thankfully you haven’t dropped one of those yet. Art supplies, some pandemic masks, shoes – who orders shoes without trying them on? Damn, this one is heavy. You’re not allowed to ask for help, even though this package is a large, awkward one, probably close to 50 pounds. “Just sort of slide it along,” Mark had said about these. Easy for him to say.

Argh, dammit! Was that a back twinge as you were sliding it along, like you were told to do? Maybe it’ll go away in a minute. What’s in this stupid package, anyway? Gold bricks? Who cares? You’re ready to be done with this shift that’s still barely half over.

You get through it. Payday is coming soon. So is rent day. $15.75 an hour means that the difference between the two won’t be that big. You get out past 7am because you got to spend an unpaid 20 minutes or so in the swirl of end-of-shift nonsense of dropped lanyards, dazed and tired glances, and worst of all, the metal detectors – they must think people would be stuffing a dozen Rolexes in their pockets otherwise. But the bus ride home is just before the morning rush hour really kicks in, which is nice. Your pal isn’t on the ride back, and you wonder how someone can work another job part-time on top of this one. Loads of your other coworkers have school classes they head to after work. You just want to melt.

You get home, soaked (really need to get an umbrella), just as the roomies are headed out the door to their jobs. Time to cook some… dinner? Breakfast? You still haven’t figured out what to call meals these days. At least the house is quiet, even if the world outside is just gearing up for another day. You want to nap, but you know that’ll just mess up your cycle some more.

As you heat up the stove, you remember something your coworker said on the bus to work a couple of days ago. Something about Amazon workers in the States fighting the company and winning. Getting better facilities – even having to demand clean drinking water at one place. Being able to do their jobs more safely. Whole groups of workers telling their own Marks that things weren’t good enough and putting a scare into them. You finally remember what they called themselves.

You type “Amazonians United” into your phone.