Updated with full results after postal votes counted.

The New Democratic Party (NDP) strolled to a solid victory in the October 24 provincial election. After a delay of three weeks to count the 660,000 postal ballots, the NDP has won 57 seats up, taking two additional seats from the Liberals in each of the Okanagan and the Fraser Valley, from 41 before the election. The Liberals picked up a seat in Metro Vancouver from the Greens, although it is going to a judicial recount, so have 28 seats. The Greens are down to 2 seats.

The NDP’s share of the votes is up more, now at 48 percent, with the Liberals down to 34 percent and the Greens remaining at 15 percent. In several seats the more right-wing parties – Conservatives or Christian Heritage – took enough votes from the Liberals for the NDP to win.

The result is not a surprise. The NDP called the snap election as they were ahead in the polls and knew bad news on COVID and economy was coming. The Liberals were a shambles with a leader seen as out-of touch and the Greens had only picked their new leader, Sonia Furstenau, a week before.

It was a lacklustre campaign with few new ideas apart from a crazy Liberal big tax cut that went nowhere. The lack of energy and the view that the result was not in doubt produced one of the lowest turnouts in 100 years at 53 percent.

The NDP swept through the outer suburbs of Vancouver, from their dominant position in the urban core and inner suburbs. On Vancouver Island the Liberals were wiped out. Even in the interior, although NDP only gained one seat, their share of the vote was up. The Liberals lost support in every part of the province while the NDP gained almost everywhere

NDP in Government

After the 2017 election, neither the Liberals nor the NDP had the 44 seats needed to form a majority government. After a lot of back and forth the Greens decided to throw their three seats in support of the NDP to form government.

The NDP was not a radical government. The Premier, John Horgan, prides himself on being a centrist. It only raised taxes on the rich by $500 million a year, after the Liberals had slashed the top taxes by $3.2 billion – so the rich were still over $2.5 billion better off. The NDP did raise the minimum wage to $15 over four years and improved some labour laws. However, it has totally failed to tackle the housing crisis of soaring rents and house prices.

The NDP has given verbal opposition to Trudeau’s pipeline (Trans mountain) yet agreed to a massive liquid natural gas development, that relies on fracking, with billions of dollars of subsidies. The RCMP invaded Wet’suwet’en, to help construction of the gas pipeline, and the NDP did nothing. This was just months after agreeing to adopt the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP)!

BC was hit early by COVID with the first death in Canada on March 8. Generally, the NDP has been seen to have handled the first COIVD wave fairly well. It had some good luck and acted as competent capitalist government, in distinction from many governments around the world, which have been utterly incompetent. It helped that the NDP was not ideologically opposed to public services.

The NDP rapidly moved to bring the private care home workers onto the public pay roll and ending them working in multiple homes. This gave staff stability and sharply reduced the spread of COVID.

NDP’s Road to Victory

BC has several distinct regions. Vancouver Island, population 870,000, has a major city, the capital region centred on Victoria with 400,000 residents and a string of smaller towns, many that were or are reliant on forestry. Metro Vancouver has a population of 2.5 million. Vancouver’s outer suburbs in the Fraser Valley have a population of 300,000 with a large farming community and growing light industry and commuters. The interior of BC is mainly resource-based, reliant on forestry, mining, fishing and gas. The Okanagan, population 350,000, is dominated by fruit farming and vineyards, and retirement homes.

On Vancouver Island the Liberals were wiped out, losing their one seat to the NDP and the NDP took a seat off the Greens so the NDP had 12 of the 14 seats. In Metro Vancouver the NDP won 31 of 39 seats taking seven seats from the Liberals. The Greens also took one Liberal seat. In the Fraser Valley, once a Liberal stronghold, the NDP won six of the nine seats, gaining four seats. In the North and Interior (excluding the Okanagan), the NDP won four of the 24 seats with no increase. The NDP gained one of the seven Okanagan seats.

The NDP made massive gains in Vancouver’s suburbs of picking up ten extra seats. This is, in part, down to the changing and growing population as more and more working class and young people move out of the Vancouver due to soaring housing costs. In some of these seats the NDP now has significant majorities of well over 1,000 votes.

Outside of Vancouver Island and the larger Vancouver conurbation, the NDP did not do so well, only picking up one seat. Apart from the rich Okanagan, most of the interior and north are overwhelmingly working class. On the coast and northern Vancouver Island the NDP dominates and has two seats in the West Kootenays. For the rest it is a Liberal stronghold, although there are six seats that the NDP has held in the recent past but didn’t come close to winning back.

How to explain the difference of working-class voters on the coast and the interior? The workers of the coast, loggers and fishers, and the hard rock miners and smelter workers in the West Kootenays were in militant unions in the post-war period – International Woodworkers of America (IWA), United Fishermen, and Mine and Mill – all at one stage communist-led. The interior forestry was later to unionize and was not as militant. Coal miners had bitter strikes and militant unions on Vancouver Island and south east BC, but that tradition seem to have been lost in the coal mines around Fernie (south east BC) and Tumbler Ridge (north east BC).

The trend of rural resource workers to vote for conservative parties is a problem for the working class across western Canada and reflects the failures of the NDP that allowed the conservatives to appear to care about jobs.

Liberals: Dismal Campaign, Dismal Result

The Liberals, really a conservative party but called Liberals, had one of their worst results in years. Their leader, Andrew Wilkinson, was out of touch. He described renting as “it’s kind of a wacky time of life, but it can be really enjoyable,” while he lives in a multimillion-dollar house and represents one of the wealthiest constituencies in BC. He referred to victims of domestic violence as “people who are in a tough marriage.” Wilkinson was slow to act on sexist and homophobic candidates, although the voters spoke clearly with Jane Thornthwaite and Laurie Throness going down to defeat.

The Liberals’ big election idea was to scrap the provincial sales tax for a year, leaving a $7 billion hole in the provincial budget. They were totally unconcerned about this leading the province to running an even bigger deficit – this from a party that for years claimed there was no money to build social housing, earthquake-proof schools and tackle poverty.

The Liberal party faces a dilemma of how to rebuild from the four disparate areas they now represent: seven seats around Vancouver that are home to some of the richest people in the province; three seats in the part of the Fraser Valley known as the bible belt, although this is changing; six seats in the affluent farming and retirement Okanagan; and thirteen seats in the working-class resource-based north and interior. And at the same time, find a new leader as the hapless Wilkinson resigned.

NDP: Where now?

The NDP called the election because it, rightly, thought it would win, and it knew there was a lot of bad news piling up. In the early summer, COVID new cases were very low, just 10 or 20 cases a day. But as time rolled on, cases began to climb. Over the weekend of the election, BC had the highest number of cases ever. Things are getting worse and the success in dealing with the first wave will be tested over the winter. Already the stress on teachers is near to breaking.

Alongside the COVID pandemic is the opioid pandemic. Between March and the end of August, 915 people died of a fatal overdose, during the same period, 208 people died of COVID. There is a lot of talk but little action on this carnage.

While unemployment is down from the COVID peak in June, 95,000 more people are still out of work compared to February 2019. The recovery has been slower in Vancouver than in the rest of the province. However, with the world economy in a depression and a second COVID wave, there are further shocks to employment. Many businesses, small and big, are hanging by a thread, only kept alive by government support. Key sectors such as tourism and the airport, entertainment and culture, and large parts of retail may not recover. So far construction is still going, as housing prices have held up, but at some point, this will end as most people are in hard times. Resource sectors in the interior rely on exports, and it is uncertain how long these will continue in a world in deep economic recession. How will the NDP government deal with the economic misery that lies ahead?

So far there has not been a wave of renter evictions and mortgage foreclosures, but the warning lights are flashing. Homelessness is still increasing in a second COVID wave as winter draws in. Up to now the NDP has largely sided with developers and refused to enact real rent control, protect low rent units and launch a massive social house building program.

The Site C dam in northern BC has mounting cost overruns and growing evidence of serious geology problems. The proposed dam, built on unstable shale in an area prone to earthquakes and home to many fracking wells, which trigger earthquakes: is a disaster waiting to happen. Unfortunately, the NDP ignored the ecological damage of the dam, its high costs and lack of demand for electricity, and suspect geology in deciding to continue construction. Now it has a nightmare on its hands.

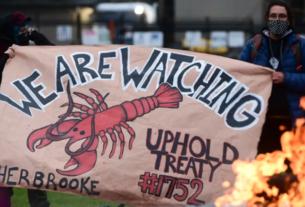

The NDP agreed to introduce UNDRIP but has not put it into practice. On many fronts – land, environment, homelessness, etc. – Indigenous issues are piling up.

Given the deep crisis of the BC Liberals, the NDP leadership will likely seek to position the NDP as a sensible competent capitalist party in the centre of politics. This may look attractive for short-term careers, but it will guarantee that the NDP government will not be able to deal with the many problems looming that are all products of capitalism.

When the NDP was a minority government, party discipline was tight, and no one challenged unpopular actions such as going ahead with Site C dam or not bringing in real rent control. With a majority, and now free of the Greens’ constraints, pressure will mount from unions, environmental, Indigenous and other activists for the NDP to take bold actions. In this situation, will some NDP MLAs have the courage to speak from conviction and raise the need for a break with accommodating landlords and big business? Could a left wing begin to emerge in the NDP? There is a huge political space in BC for such a voice.

BC has a long and proud militant working-class history with strong socialist roots. Now, more than ever, this is needed to defeat the nightmares of COVID, economic depression and climate change that capitalism is inflicting on society. Socialist Alternative is helping to build a new way forward – a socialist road that treats workers and the environment with respect without exploitation. Join us.