Canada has proclaimed multiculturalism for over 50 years, and the Canadian Multiculturalism Act was enacted in 1988. Yet Canada has a long way to go before it can claim that title in reality rather than just on paper. Although Canada is a country populated overwhelmingly by migrants and their descendants, to this day, a large portion of Canadian residents do not feel safe here.

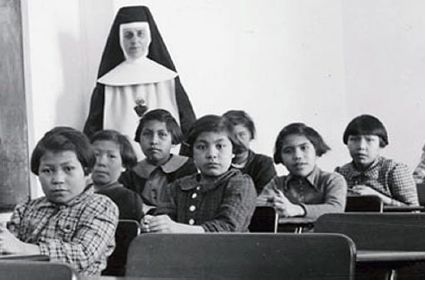

From its founding days Canada has a deep history of racism and exploitation, whether it was the attempted genocide of Indigenous people and occupation of their lands, the mistreatment of Chinese migrant workers on the Canadian Pacific Railway, or still today the exploitation of foreign agricultural workers on its farms.

“ElContrato” is a documentary film by Min Sook Lee, released in 2003, that shines a light on the lives of temporary foreign workers (TFW) in Canada. The documentary follows Teodoro, a Mexican father of four, on his journey to Leamington, Ontario for his seasonal job of working on a farm that grows tomatoes. He is hired for eight months of the year, being stuffed into one floor of a small house with nine other men and works a minimum of 10 hours each and every day. The hiring firms prefer men who have families with small children in Mexico to ensure that they go back once their contracts are up, and to make sure they don’t make trouble while in Canada. The threat of being sent back to Mexico is reoccurring.

On the farm, there are no safety or health regulations; they often work with dangerous pesticides with no protective gear or safety training. If a worker gets sick or needs medical attention, the owners will often delay taking them to the hospital for days, if not weeks. If they can no longer work due to an injury, they are sent back to Mexico on the next flight out. Oftentimes, employers or management would verbally and physically abuse them to the point where one worker expressed the sentiment that “in my mind slavery has not disappeared, we are the slaves; I want them (the owners) to realize at least a little that the money they make is due to the work we do.” Their identities are stripped from them, and they are treated with scorn, not only from employers but also from locals who don’t like how different they are. There are many incidents of assault, harassment, and outright theft.

Why don’t workers complain? The local police don’t see them as people, and often say they will “contact their owners” over any problems. Additionally, a lot of the services the government offers is only in English or French, and many of them only speak Spanish. The majority of the workers don’t have high levels of education. Their room to bargain or protest for better working conditions is constrained by the threat to send them back to Mexico and someone else taking their place.

In Ontario, the Agricultural Employees Protection Act does not allow agricultural workers the right to join a union. This restriction has been upheld by the Supreme Court in a 2011 ruling. Québec’s Superior Court ruled in 2013 that seasonal farmworkers had the right to unionize. But a year later the Québec Liberals passed Law 8, which took away that right. Even where it is legal to form a union, such as in BC, the employers go to great lengths to block unionizing.

Usually, because of these barriers, workers have two choices for complaints: go to the owner, whom they have a problem with, or to the Mexican Consulate, which is in the pocket of the plantation owners. The Mexican Consulate, in order to keep good relations with Canadian business owners, as well as to entice foreign investors, is usually on the side of the owners and will blacklist and send home workers who make “trouble.”

Yet, in spite of all the discrimination, many of the workers come back year after year. They come because the conditions in their home countries are even worse with mass poverty and unemployment. They come to feed their families.

When the film was made in 2003, the pay in Ontario was $7.25 an hour without paid overtime, holiday pay, or any days off. Workers had to pay unemployment insurance premiums (EI) and into the Canadian Pension Plan, yet very few would ever receive any benefits. And if that wasn’t enough, some employers deduct their plane ticket fees from their wages.

Have things improved over the years? In 2019, Canada admitted 72,000 people doing agricultural work on a temporary workers’ visa. Those coming on a temporary workers’ visa are tied to a specific company, and if a worker is fired, they have no support, no money, no housing and no way to get a different job. Their livelihood depends on being in the good graces of their employers. Immigrants and temporary workers are often left doing the “dirty jobs” that Canadians won’t take for the very low pay on offer. Employers under capitalism want a source of cheap continuous labour, and thus they often employ single mothers and workers with families back in their home countries. Furthermore, agricultural workers are often employed in small rural towns where they experience racism, and they don’t have the right to stay in Canada.

Then COVID hit. In the first six weeks, more than a thousand migrant farm workers complained about widespread wage theft, sub-standard housing, lack of protective equipment, food shortages, intimidation, surveillance, and increased racism at their worksites. In 2020, Ontario reported 12 percent of its migrant agricultural workers had tested positive for COVID, with four deaths. If that wasn’t enough of a nightmare, employers used the pandemic as an excuse to lock workers up on farms and forced them to buy food from their employers at inflated prices.

The spread of COVID among farmworkers lifted a curtain on their living conditions. One migrant worker stated, “We are living in conditions of modern-day slavery.” Workers were living in overcrowded buildings with insufficient privacy, toilets or cooking facilities.

At the end of 2021, Canada’s Auditor General released a damning report on the treatment of temporary farm workers. Employment and Social Development Canada is supposed to inspect the conditions on farms, yet the vast majority of inspections were “shoddy.” After criticism in 2020, the report found that in 2021 things were even worse, with 88 percent of all inspections showing deficiencies. Inspectors also failed to “complete the vast majority of inspections in a timely manner.”

A similar situation exists with temporary workers in caregiving, food service and meatpacking plants.

A study of in-home caregivers found that one in three had lost their jobs, and of that, a third were not able to access CERB or EI. Of the ones who had kept their job, half reported working far longer hours then they were paid for — wage theft. One in three said that their employers wouldn’t let them leave the house, take transit, buy groceries, or even visit the doctor. One nanny reported being fired for going on a walk. The hypocritical thing was that their employers would leave the house regularly, yet the workers, most of whom were racialized women, were not allowed out.

Foreign caregivers, unable to find the resources to return home, were stuck in the houses of their employers, at their mercy. Workers were still forced to work without extra pay, benefits, or sick leave. The employer of Maria Lopez, a Filipino worker, wouldn’t let her take even a few hours off to go to church on Christmas and send money back home to her children. They threatened not to pay for an entire day’s work if the quota wasn’t met. She said, “I know that I am not born here in Canada, that I am just a foreign worker, but I am a human.” She spoke about unsafe work, including being forced to work during the hottest days, to the point where she would get nosebleeds and still be forced to work.

The federal government has said they will fix gaps in the Temporary Foreign Worker program, but don’t hold your breath.

There are many gaps in Canada’s immigration system. One of the problems is the lack of recognition of foreign credentials. According to the 2019 study, “We Don’t Want to Hear About Discrimination,” politicians ignore the evidence of discrimination against foreign workers. Newcomers of certain ethnic backgrounds have more difficulty in finding work at their level of qualification. Even workers with favourable previous work experience, language skills, and education faced significant hardships in getting their credentials recognized. The study found that in order to be recognized as a licensed professional, an immigrant might have to meet different and sometimes conflicting demands from coworkers, employers, educational institutions, and both federal and provincial laws. The reality is, whatever the level of education or training of an immigrant, even after spending 10-15 years in Canada, immigrants were still twice as likely as Canadian-born workers to be in low skilled occupations.

This is linked to a domino effect of various other structural disadvantages, such as housing discrimination, which means that workers are pushed into low-income areas, often involving long commutes to work, which means less time to look for other jobs or upgrade qualifications. All these pressures may lead to mental stress and ill-health.

There is a lack of government supported programs, such as to learn and improve English or French. Learning resources have been cut back, are centred on university campuses, are often expensive, and there is no unified approach to providing education for new arrivals. Canada’s system has multiple barriers to new arrivals, which leave profound questions about Canada’s claim to be multicultural and welcoming to immigrants.

Temporary foreign workers are cheap labour, and super exploited to boost profits. In May the Canadian government announced a huge boost in the portion of -temporary foreign workers that can be hired in any particular sector. Previously TFWs could only be a maximum of 10 percent of the workforce in accommodation and food services, including meatpacking plants — now it is 30 percent. These industries are notorious for low wages and unsafe conditions during COVID — Alberta’s meat plants were the scene of multiple fatal COVID outbreaks.

Temporary foreign workers do not have basic human rights and are therefore mistreated and abused. Canadian food production is utterly dependent on cheap migrant workers. Their lack of rights holds down their wages as well as other workers’ wages. The workers who put food on everyone’s tables should have full rights, including to join a union. If someone works in Canada and pays taxes, they work should be able to gain permanent residency and citizenship. They should have the same rights as all other Canadians, including to bring their family to Canada.

The same is true for workers who care for patients in seniors’ homes, look after children in people’s homes and for other groups of super exploited workers. Employers are using cheap labour to boost profits and hold down wages.

Canadian unions and the NDP should lead a campaign to end this racist exploitation. Organized labour should fight for equal rights for all workers. An injury to one is an injury to all. Unity is strength!