“Even as the West pushes for a diplomatic solution to escalating tensions between Russia and Ukraine, it is bracing and today further preparing for the possibility of war.” These words led off the January 24 broadcast of CBC’s flagship evening news show “The National,” and they encapsulate very well the tone that the Canadian media as a whole has taken toward the ongoing Ukraine crisis for weeks. Canada and other democracy-loving, diplomatic NATO countries, this narrative goes, are acting in a very measured and purely defensive manner, doing no more than reacting to the aggressive and cynical moves of Vladimir Putin. Meanwhile the Russian leader, we are warned, must not be “appeased.” It is claimed that his nefarious, even megalomaniacal ambitions to expand Russia’s influence won’t stop until he has reassembled all of the former parts of his late and beloved USSR under the Kremlin’s control — and who’s to say he would stop even then?

If this assessment of the media’s tone sounds like an exaggeration, it’s at most only slightly so. Take, for instance, the amateur psychoanalyzing of Putin in The Globe and Mail which attaches greater emphasis for the Russian leader’s actions to his 5’6” height than to the whole of international relations or the needs of the Russian ruling class of which he is the head. But beyond the realm of quack psychology, the reality is that the events in and around Ukraine are part of larger geopolitical conflicts among various imperialist powers — the United States, Russia, China, Germany, France, and others — as they struggle for markets and global influence, as our sister organization in Russia explains.

Will there be an attack?

A full-fledged invasion, far from “inevitable,” is highly unlikely. Even Ukraine’s government has shifted tack and is now downplaying its likelihood, with Aleksey Danilov, secretary of Ukraine’s National Security and Defence Council, saying that “We do not see today any basis for confirming a full-scale invasion. It is impossible for this to even happen, physically.” Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky also tried to throw cold water on the overheated war talk, even criticizing Canada and other countries for withdrawing families of diplomats.

An invasion of Ukraine by the more than 100,000 nearby Russian troops stationed in Russia and Belarus would result in huge military and civilian casualties, destabilize the entirety of Eastern Europe, and lead to potentially massive domestic ramifications in Russia itself. Putin, who has recently consolidated influence over Belarus and Kazakhstan, and who leads a country much less friendly to the idea of war than in 2008 in Georgia or 2014 in Crimea, Luhansk, and Donetsk, is somewhat constrained by domestic factors and an unstable economy from grasping for all that he might want. Other supposed Kremlin plans, such as the United Kingdom’s allegations that Russia is considering engineering the removal of Zelensky and his government through a coup, and replacing them with a puppet regime, would almost certainly fail without an invasion and its concomitant devastation. The possibility is not entirely impossible and it would indeed “change the world,” as U.S. president Joe Biden said on January 25.

A multi-day cyberattack on Global Affairs Canada, announced on January 19 after it had ended, was heavily implied by the government and media to be Russian in origin. Regardless of whether or not that’s true, similar lower-level, plausibly deniable attacks could come and are a far likelier course for Russia to take, but these would not represent a qualitative escalation in hostilities. Energy politics could enter into events as well, as Russia has in the past redirected natural gas exports away from Europe as a way of exerting political pressure. Currently, however, Russia wants German approval of the already-completed Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline, which bypasses Ukraine and could deny that country billions of dollars in transit fees.

The real risk is that unpredictable miscommunications or mistakes, amid the heightening tensions, could lead to an escalation that genuinely gets out of the control of the leaders on either side. When both sides have thousands of nuclear weapons at their command, a slip-up of a certain kind at a certain time could have massive consequences. A particularly frightening example is the 1983 incident in which a Soviet military computer malfunction led to a false alarm of a U.S. nuclear attack that nearly led to a real nuclear counterattack. Of note is that this unanticipated technological glitch occurred at a time of highly escalated tension between the USSR and the United States, in the midst of a missile race and with the Soviet Air Force having shot down a South Korean civilian airliner in Soviet air space just weeks before. In this manner, increased Canadian intervention would provide an additional destabilizing element that could increase the chances of a spiral into consequences no one can desire or predict.

Canada’s Motives

Why does the Canadian state show such interest in a relatively poor country on the eastern edge of Europe? There are both domestic and international reasons. About 1.4 million Canadians can trace full or partial family history to Ukraine, immigration from which was especially high to the prairie provinces in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Many of these Ukrainians played an important role in Canada’s labour movement. The Ukrainian Hall in East Vancouver provided shelter for workers assaulted by police in the 1935 Battle of Ballantyne Pier, in a longshore workers’ strike. The Ukrainian Labour-Farmer Temple Association, founded in Winnipeg in 1918, had expanded across Canada and grown to over 10,000 members in 200 branches by 1939. As part of the Canadian government’s anti-democratic war efforts, it was banned in 1940.

Later, with support from the Canadian government, the Ukrainian Canadian Congress (UCC) was established as a safe and anti-left voice. Disgracefully, Canada welcomed 2,000 Ukrainians who had fought alongside the Nazis in World War Two, where they had massacred Poles, Jews, Russians, and fellow Ukrainians. These people were used to attack unions, undermine the left-leaning Ukrainians, and help consolidate the UCC. The Alberta and Canadian governments have helped to fund the Ukrainian Youth Unity Complex in north Edmonton, which has a statue of Nazi collaborator Roman Shukhevych.

Canada is today the country with the greatest number of ethnic Ukrainians outside of Ukraine and Russia. But the familial history of a segment of the population is far from sufficient reason for the Canadian government to push for military conflict. Canada’s trade ties with Ukraine, while not negligible, are also not enough on their own to warrant the Canadian state’s intervention at this level. Bilateral trade, headlined by seafood, agricultural machinery, and prepared cranberries, totalled between $300 million and $380 million per year since the implementation of the Canada–Ukraine Free Trade Agreement in 2017.

At the base, Canada wants a strong and friendly Ukraine not for the benefit of the Ukrainian people, nor for domestic reasons (economic or sentimental), but primarily as a thorn in Russia’s side. The Arctic is set to be a much more important theatre of international conflict in the coming decades with new shipping routes and increased access to resource exploitation due to climate change and global conflict increasing generally. China has already stated its intention to be acknowledged as a “near-Arctic state” and this will further pressure Canada and Russia to stake their own claims. On a larger scale, Russia has drawn closer in recent years to the West’s new cold war enemy, China, as shown by the recent statements of Putin and Xi at the start of the Winter Olympics. Canada, meantime, is tightening its ties to the United States. Russia and China support each other diplomatically, and Russia is a major supplier to China of energy and raw materials. China largely backs Russia in the current conflict, with a future eye to putting its own screws on Taiwan. Also, China gains the support of the largest Arctic country in its drive to access the far north.

Canada’s Actions

On January 21, the Canadian government announced a $120 million loan to Ukraine, with the minor caveat that this money will not be used for the purchase of weapons. (Nearly always unmentioned when deals like this are discussed is that the recipient can simply move other money around to devote to the stated “off-limits” use.) This has been derided as insufficient by the UCC, the Conservative Party, and a large majority of the media, exemplified by a CTV News interview with international development minister Harjit Sajjan in which host Evan Solomon angrily demanded that Canada directly arm the Ukrainian military with whatever weapons it might ask for. Some outlets have called for the reallocation of weapons once earmarked for Kurdistan, though never delivered there, to Ukraine.

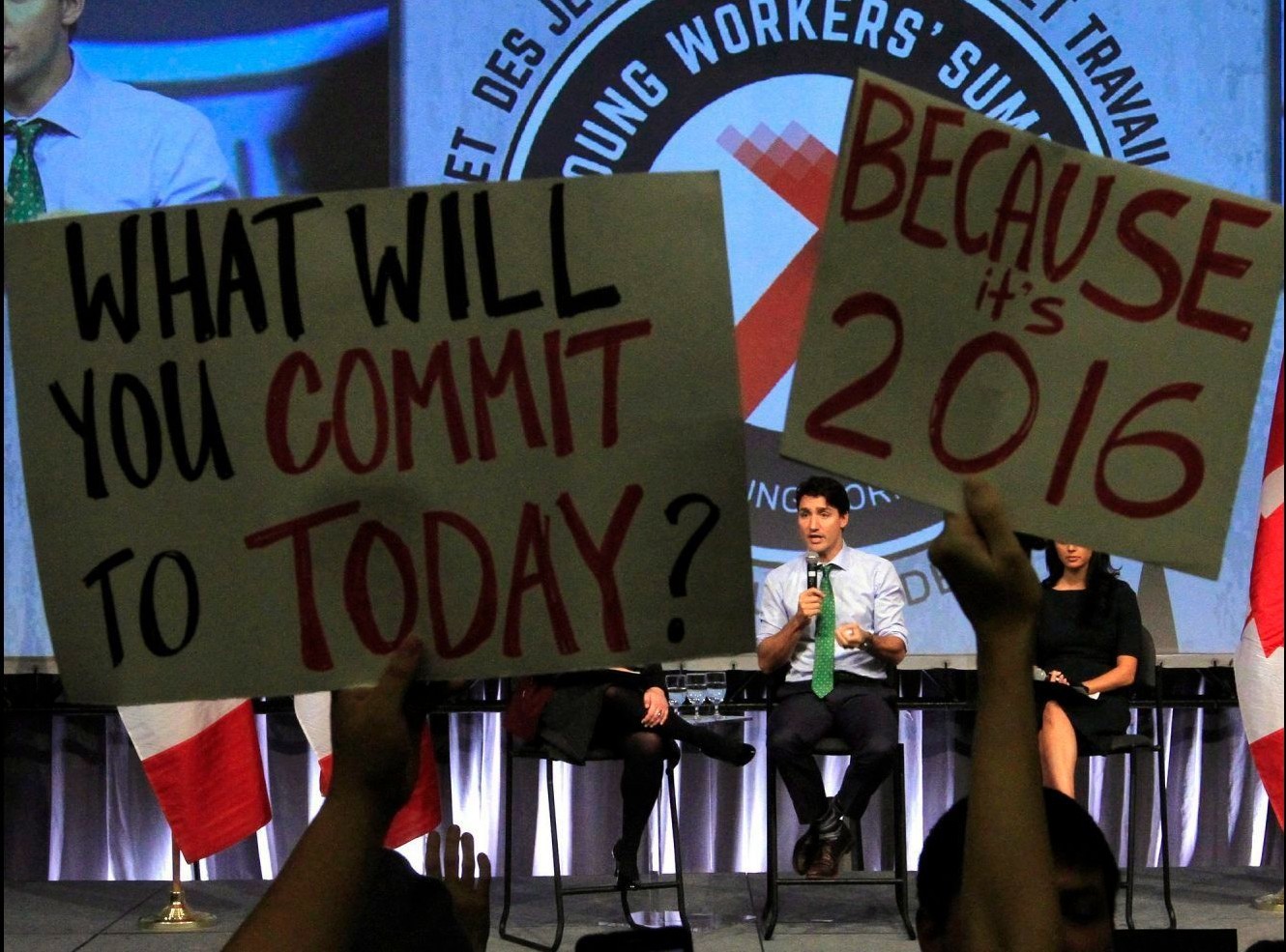

Justin Trudeau has not yet taken these steps, so far officially limiting Canada’s material aid to “shipment of non-lethal weapons to Ukraine, intelligence sharing, and support to combat cyberattacks.” News shows are regularly contrasting this with pallets of weapons and ammunition from the United States and the United Kingdom being unloaded before TV cameras on Ukrainian airstrips.

However, on January 26, Trudeau announced an extension and expansion of Operation Unifier, the 200-troop Canadian Forces training action in western Ukraine, which has worked alongside the neo-Nazi Azov Regiment of Ukraine’s National Guard. This regiment has engaged in torture and attacks left-wing groups and ethnic minorities. Canada’s military and civilian leadership have known about this for years. Unifier, launched in 2014, was previously set to end on March 31, but will now continue to 2025 and with an immediate increase of 60 soldiers, with the total possibly rising to 400 in the future. This is in addition to special forces Canada has sent from the Canadian Special Operations Regiment to Ukraine as of January 9, although the government has officially been silent on the deployment. If they are forced into an acknowledgement, they will likely say that the units are there for “training,” “evacuation plans for embassy staff,” or some other such respectable and humanitarian task. On January 31, defence minister Anita Anand stated that Canada may yet send more money and weapons. It’s also likely that Canada will soon reaffirm and possibly expand its commitment to Operation Reassurance, its 900-member force in Latvia.

Canadian left

What is the Canadian resistance to these escapades? The NDP’s response to the current crisis has been lamentable, though entirely predictable. The party that loudly supported Canadian participation in the US-led 2011 attack on Libya (among other imperial adventures) has not changed its tune in the decade since. It supports the extension of Unifier and Trudeau’s transfer of “non-lethal military equipment,” dissenting merely by the expression of a vague and pious wish that “diplomacy” be given an honest go, with a tacked-on plea “for women from all sides of the conflict to be included in negotiations and discussions on the future of the region.” Winnipeg MP Leah Gazan, one of the party’s more left-leaning legislators, was forced to apologize after tweeting criticism of Canada’s support for an anti-Semitic, neo-Nazi and fascist militia, obviously referring in an accurate way to the aforementioned Azov Regiment.

Left of the NDP, much of the criticism of the Canadian government’s support of Ukraine’s current government is focussed on the domestic influence of right-wing political pressure groups such as the UCC, Second World War memorials in Canada to Ukrainian enlistees of the Waffen-SS, and deputy prime minister Chrystia Freeland’s Nazi-collaborator grandfather. There is also mention of the alleged 1990 verbal pledge made by US secretary of state James Baker to faltering Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev that NATO would expand “not one inch eastward” (if Gorbachev really believed his American counterpart, he was naive in the extreme). However, these are secondary or even tertiary issues and should not be a central focus of the left’s criticism. Much more important to attack are Canada’s continued membership in NATO, and the massive new spending on submarine, frigate, and fighter jet programs that the Trudeau government is shepherding along.

For a long while, Stalinist-influenced groups and individuals in Canada have looked at this and many other international conflicts through an oversimplified “the enemy of my enemy is my friend” lens. This is at least partly reinforced by nostalgia for the Russian-dominated USSR, which in spite of its raft of deformations did act as a non-imperialist foil to US imperialism for decades.

Genuine socialists have always recognized that the working class of one country has more in common with workers in another country than the ruling class of their own country. The Communist Manifesto ends with “Workers of the World Unite.” When the socialist and union leaders of most countries abandoned this core view and voted to support World War One, leading to bloody slaughter, the German revolutionary Karl Liebknecht correctly and courageously declared that “the main enemy is at home,” i.e., the ruling class of one’s own country. (This is a lesson that Russia’s Communist Party, long a stalwart supporter of Putin’s capitalist and nationalist United Russia party and today one of the country’s loudest voices for war, would do well to remember.)

But Liebknecht, Lenin, and the other genuine socialist internationalists of their time did not take from this truth the false position taken by many of today’s left that the way to oppose their domestic rulers was to support the rulers of the other side. Indeed, their view was that the defeat of their own ruling classes — whether headed by a tsar, kaiser, president, or prime minister — would provide a huge inspiration and impetus to the oppressed classes of the “enemy” nations to rise in order to accomplish the same. In 1914 this was a minority view, but in 1917 the workers of Russia overthrew the tsar and then the successor government, which had continued the war and stonewalled social reforms. The Bolsheviks withdrawal from the slaughter, and the mutiny of the German navy and army in November 1918 finally ended the war.

This view is entirely absent from the proclamations of today’s Western Stalinist and Maoist groups, which give uncritical support for the right-wing capitalist regimes in Moscow and Beijing. Their views toward enemies of US imperialism would have been alien to Lenin, Liebknecht, Leon Trotsky, Rosa Luxemburg, and the other foremost communists of a century ago.

Ironically, in their “practical politics,” the demands of these groups end up converging with those of the NDP as abstract, pacifist calls for “peace” and “democracy” that provide no meaningful path toward winning either. The role of the working classes of the Western countries is perhaps mentioned, perhaps not. The working class of Ukraine itself, and its potential as a progressive political force, are essentially assumed not to exist. Although many Ukrainian unions are largely paper organizations, it is not believable that with 43 percent of workers in unions all “Ukraine is nothing less than a den of neo-Nazis and fascists.”

What we say and do

Our International Socialist Alternative sister party in Russia, Sotsialisticheskaya Alternativa, has been at the forefront of opposing Putin and the reactionary big business people who are the key pillar of his rule. They do so in ways far more honest and effective than the NGOs, which Putin also pillories, because those liberal organizations defend essentially the same capitalist system as the autocrat does, just with a more Western-friendly orientation.

Ukrainians have the right to national independence. Trotsky, himself born and raised there but a socialist internationalist not a Ukrainian nationalist, reiterated as such in 1939, at a time when Stalinism’s crimes had soured countless Ukrainians to the idea of socialism. Those crimes helped to lead to thousands of Ukrainians taking the unthinkable step of siding with Hitler in the genocidal war that followed.

Russians and other minorities in Ukraine also have the right to choose their political fate, free from the threat of violence from Kyiv or Moscow. Ethnic groups who find themselves a minority within a state must be guaranteed the right to a measure of autonomy, including the right and ability to be educated and conduct business in the language of their choice, which the Ukrainian government has recently curtailed. The Russian government has long done the same to many of its minority ethnicities, especially those who practice Islam.

When it comes down to it, the government of Canada can be as little trusted to guarantee the independence of any nation, whether inside or outside its own borders, as the governments of the United States, Russia, or Ukraine. The countless conflicts, currently increasing and not decreasing, around questions of national self-determination will never be satisfactorily resolved under capitalism. From Québec to Xinjiang, Chechnya to Punjab, Donetsk to Wet’suwet’en — these conflicts, different as they are, will continue to rumble and sometimes explode. They will be tamped down by their oppressor nations, and often be cynically “supported” by the rivals of those nations, at least until the conflict is no longer useful and the support is withdrawn, as has been done to the Kurdish people recently. Imperial conflict of this kind, of manipulation of small nations by large nations in their battles against other large nations, must necessarily continue as long as capitalism does.

The best way for Canadians to battle against this is not by cheering on the Canadian government to send more weapons and troops to Eastern Europe or anywhere else. It is through the opposition of working people in Canada — by protests, strikes, union work, electoral campaigns, and other methods — against our “main enemy at home,” and through helping our compatriots in other countries on both sides of the trenches to do the same. It is through the ambitious and dedicated building of a socialist movement in Canada and abroad which will, once it has built the sufficient strength, rip the power out of the hands of the future Putins, Bidens, and Trudeaus, and ensure that the current war scare will not be endlessly repeated.