Tony Saunois is a member of the Committee for a Workers’ International.

In re-building a socialist movement, lessons of coup need to be learnt The terrorist attack on the Twin Towers in New York in 2001 was not the first ’9/11’. In Chile, on 11 September 1973, a bloody coup, led by General Augusto Pinochet and backed by the US administration, overthrew the democratically-elected, Left government of President Salvador Allende. In its aftermath, thousands of trade unionists and socialists were slaughtered and thousands more imprisoned, tortured and exiled. On the fortieth anniversary of the coup, Chile is embarking on a new presidential election scheduled for 17 November 2013. Following a massive student movement, which has continued to rock the country, the first possible important steps are being taken to rebuild an alternative for the working class. The two main political blocks, the ‘New Majority’ and the ‘Alliance’, both represent the existing ruling elite. They have offered no alternative for the working class and poor of Chile. The parties of the “left”, like the Socialist Party and Communist Party, have long since abandoned the radical left ideas they adhered to during the Allende-era. Like there counterparts internationally, these parties have embraced capitalism and the market and offer no alternative to the working masses. Former President Michelle Bachelet of the Socialist Party and New Majority coalition is standing again, as no other credible candidate emerged from the former governing coalition. Bachelet is the daughter of air force General Bachelet, who supported Allende and died under torture following the coup. The right-wing Alliance is fielding Evelyn Metthei, daughter of former Pinochet junta member, General Matthei. Neither candidate offers anything but a continuation of neo-liberal policies. Yet also running in this election is Marcel Claude, the candidate of the Humanist Party and Left Alliance. Defending the students’ movement, demanding free quality education for all, and re-nationalisation of the copper industry, banks and big monopolies, Claude’s campaign has drawn big crowds and won enthusiastic support from workers and young people. The campaign represents an important step forward in re-building the workers’ and socialist movement. To build on this and to take it forward following the November election, the lessons from the bloody coup 40 years ago need to be learnt by a new generation. The reasons for the defeat 40 years ago are relevant for the workers and youth of Chile and all countries. Tony Saunois, 11 September 2013 To read about the background to the coup and the lessons workers and youth must draw from it, we are re-publishing, ‘The other 9/11 – 1973 bloody coup against Popular Unity government, lessons for today’, by Tony Saunois, written in 2011.The 1973 bloody coup against the Popular Unity government and the lessons for today

The socialist and communist parties

The PSCh in that period was a completely different animal to that which exists today. Formed in the early 1930’s, it was born in opposition to the Stalinised Communist Party, and was a larger party. It was far to the left of the PCCh. It included in its constitution adherence to Marx and Lenin and called for the establishment of a Socialist Federation of Latin America. Allende, although in many speeches endorsing Marxism, was not the left candidate for the PSCh but was the party’s ‘compromise’ candidate for the presidency elections. The victory of the UP followed a series of social upheavals which rocked Chile during the 1960’s. The middle class was split with a section becoming increasingly radicalized. This affected the centre-right capitalist party, the Christian Democrats (DC). A section eventually split and formed the Christian Left (IU) and the MAPU, which ended up in the UP and even on its ‘left-wing’. Even Tomic, the DC’s candidate against Allende, reflected this process by endorsing the “relevance of Marxism”.UP implements reforms

Within weeks of forming the government, the Popular Unity (UP) introduced important reforms. Free schools meals were decided straightaway, wages were raised and land reform began to be implemented. Under the impact of the revolution, the powerful copper mines, largely owned by US multinationals, were eventually nationalized, along with important sectors of the banks. Plans were announced for the nationalization of nearly 100 companies. By the time of the 1973 coup, over 40% of the economy was in state hands. From the beginning, the Chilean right wing and the military, together with US imperialism, began to plot the overthrow of the UP government. Initially, they hoped that a policy of de-stabilization and economic sabotage would be sufficient to undermine the new government and trigger its down fall. American President Nixon’s orders were “to make the economy scream”. A trade embargo against Chile was established. These forces of reaction financed armed terrorist attacks by the fascistic ‘Patria y Liberdad’, and a bosses’ lock-out was led by truck owners. Allende won the election with 36.3% of the popular vote. The capitalist parties in the Congress allowed him to take the presidency, on a minority vote, because he fatally agreed to a constitutional pact that meant he was not to touch or interfere with the armed forces. This was to prove disastrous, as events unfolded. The ruling class hoped that they could undermine Allende’s support and rally their supporters and those who were wavering. At first, they attempted to do this “constitutionally”. They used the Congress and Senate to block and disrupt the government. Eventually, they hoped to impeach Allende, for which they needed a two-thirds majority, but which they failed to obtain. The undemocratic nature of the parliamentary system meant that the UP did not have a majority in either Congress or Senate. However, this policy rapidly began to unravel as electoral support for the UP not only consolidated but increased. Every attempt to undermine the government radicalized the working class, pushed the revolutionary process forward and increased electoral support for the government. During the 1971 mayoral elections, UP candidates took over 51% of the vote. Even at the Congressional elections, in March 1973, the pro-capitalist parties hope to win 66% of the vote and two-thirds of the seats, which would have been enough to impeach Allende. They failed and the UP won over 44% of the vote – more than when Allende was first elected!Role of the working class

Unlike Venezuela today, the working class consciously saw itself as the leading force in the revolution in Chile. While Allende enjoyed enormous popularity, the personality cult and top-down administrative methods, present today in Venezuela, were not predominant under the Popular Unity (UP). In Chile, the working class had built a series of powerful political and social organizations with a long history and tradition. There was intense debate between the different organizations and parties, and also within them, about program and strategy. The leaders were challenged and, on occasions, opposed by workers. Where the old organizations proved inadequate, the workers built new ones that were more responsive to their demands and needs in the work places and the local communities to lead and defend the revolution. The character of the revolutionary process under the UP had a massive effect internationally. This was far greater than the sympathy shown by layers of young people towards Chavez in Venezuela. The election of a “Marxist” President and government in Chile, and the leading role in the process of the working class, enthused the working class globally. It also opened a discussion on how to achieve socialism and the role of the state. In Britain, meetings of the trade unions and the Labour Party debated the Chilean experience and its lessons for the workers’ movement internationally. Supporters of Militant (the forerunner of the Socialist Party) moved resolutions for the Labour Party congress, drawing on the lessons of Chile and, amongst other things, demanded trade union rights for the Chilean armed forces. Every attempt at counter-revolution in Chile provoked a further radicalization and mass mobilization by the working class and its allies. The bosses’ strike in 1972 led to the rapid growth of organizations in the industrial districts and the formation of the ‘cordones industriales’ (‘industrial belts’). These were elected committees in the work places, which began to link up on a district and even a city-wide basis. Delegates were elected and subject to recall. In the industrial city of Concepcion, in the south of Chile, they formed a city-wide Popular Assembly. Workers’ control was established in many workplaces throughout the country. Food shortages and speculation caused by the embargo and sabotage of the bosses resulted in the formation of the JAP’s – ‘peoples supply committees’ – which organised food distribution and tried to prevent speculation. The cordones increasingly assumed a political role to advance and defend the revolution. This was partly driven by the frustration of workers at the undemocratic parliamentary election system, which meant that the UP lacked a majority in the Congress and the Senate, despite forming the government. One of the most radical of the cordones was in the industrial district of Cerillos. It adopted a political program that, amongst others things, declared “support for president Allende’s government, in so far, as it interprets the struggles and demands of the workers; expropriation of all monopoly firms with more than 14 million escudos in capital or are of strategic importance to the economy; workers’ control of all industries, farms, mines, through delegate councils, delegates being recallable by the base; a minimum and maximum wage; peasants’ and farmers’ control of agriculture and credit and to set up a Popular Assembly to replace the bourgeois parliament”. The working class, were far to the left of the government and its leaders, both of which were dragged into taking more radical steps by the radicalized workers and youth. In response to the armed attacks being unleashed by the fascistic Patria y liberdad, as the police and army stood by, workers’ defence squads were formed. These developments terrified the ruling class and imperialism. The revolution spread to the countryside, where farm workers and peasants occupied land and carried out a program of agricultural reform. Over 10 million acres of land were re-distributed.Plans for a military coup

The ruling class, in conjunction with US imperialism, began to rapidly develop plans for a military coup as the prospects of ousting the Allende government through parliament diminished and the revolutionary process continued to advance. Yet, at every stage, the leaders of the PCCh (Communist Party) and sections of the PSCh (Socialist Party) acted as a brake and tried to hold back the revolutionary process, arguing that the “democratic” bourgeoisie must not be alienated and defended the “constitutonality” of the armed forces. The left of the PSCh, including figures like Carlos Altamirano, the party’s General Secretary, argued for the creation of “Peoples Power” and the strengthening of the revolution. However, despite using very left-wing revolutionary and Marxist rhetoric, the left of the Socialist Party failed to propose specific demands or initiatives to take the revolution forward and to overthrow capitalism, while plans were being laid for a reactionary military coup. These developments led to a polarization within the Popular Unity (UP) coalition and splits within its component parties, between the left and right. Yet the forces of reaction laid out very detailed and precise plans. Henry Kissinger, US Secretary of State in the Nixon administration, cabled the CIA chief in Santiago: “It is the firm and continuing policy that Allende be overthrown by a coup.” The preparations were laid. Reaction bided its time, waiting for the appropriate moment to strike. It was known throughout Chile that a coup was not only being discussed but planned for. At the time, it was joked that Allende spent 23 hours out of every 24 hours worrying about the army. In June, sections of the military, from the tank regiments, moved prematurely and organized a rebellion against the government – the so-called ‘Tancazo’. It was too early and was put down by the military, under orders from Allende. General Pratts, a supporter of Allende, who quelled the attempted uprising, was later murdered after the successful coup in September 1973. The ‘Tancazo’, in June, acted as the whip of counter-revolution and provoked the working class to take further revolutionary measures. It had the same effect as Spinola’s failed putsch, a few years later, in March 1975 during the Portuguese revolution. In Chile, the failed June coup was followed by the announcement of a plan for massive nationalizations and by an increasing demand by the working class for arms to fight the threat of reaction. Yet despite the ‘Tancazo’, neither Allende nor the other leaders took steps to strike against the military or to mobilize and arm the workers. Trade union rights were not given to the ranks of the army, no attempt was made to try and organize or to build support amongst the ranks of the armed forces, many of whom supported the revolutionary process. The conditions existed to split the armed forces but decisive action was necessary. Yet the leaders of the UP were imprisoned by the idea, especially emphasized by the Communist Party, that a “progressive wing” existed amongst a section of the ruling class. Allende proclaimed his determination to avoid a civil war. They had a policy of respecting “the constitutionality of the armed forces” and of a gradual measured step by step program of reform that, eventually, would establish socialism. In practice, this ‘stages theory’ allowed the ruling class time to prepare its forces to strike, when the moment was most opportune. It resulted not in the avoidance of a civil war but in the drowning of the revolutionary movement in blood.Constitutional pact

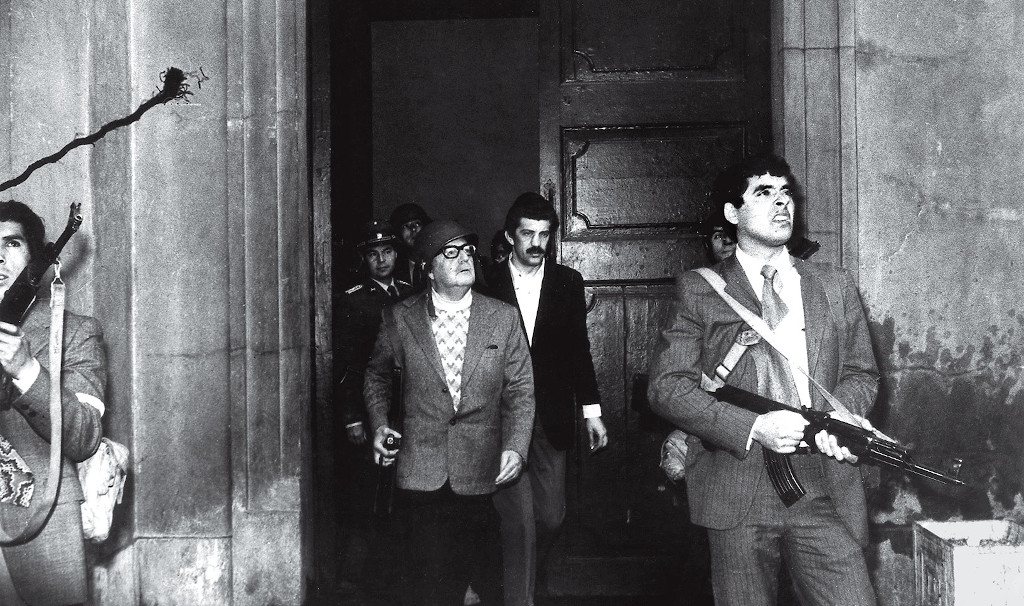

From the beginning, Allende laid the ground for his own defeat when agreeing not to touch the army in the fatal ‘constitution pact’. The state machine was left in the hands of the generals and reaction, without any challenge. Allende adopted a policy of appeasement – even of appointing three generals – including Augusto Pinochet to the Cabinet, in a doomed attempt to reassure the military and ruling class. Allende had the support of four out of twenty two generals but his policy rendered him impotent, as his supporters were systematically removed and eventually executed. The Republicans in Spain, in the 1930’s, playing ‘musical chairs’, at least moved Franco around the country, to try and prevent the organization of the fascist military revolt. But Allende made Pinochet a Cabinet minister and even Chief-of-Staff, following the forced resignation General Pratts by pro-coup conspirators. Moreover, when sections of the rank and file tried to come to the aid of the revolution and oppose a coup, the policy of “constitutionality” meant Allende scandalously supported the pro-coup reactionary hierarchy. In August, in the naval port of Valpariso, 100 sailors were arrested for “dereliction of military duty”. In fact, they had discovered plans for the coup and declared they would oppose it. In what was referred to as his darkest hour, Allende, supported the hierarchy in the navy as it arrested and tortured this group of naval ratings!