Vincent Kolo is a contributor to chinaworker.info.

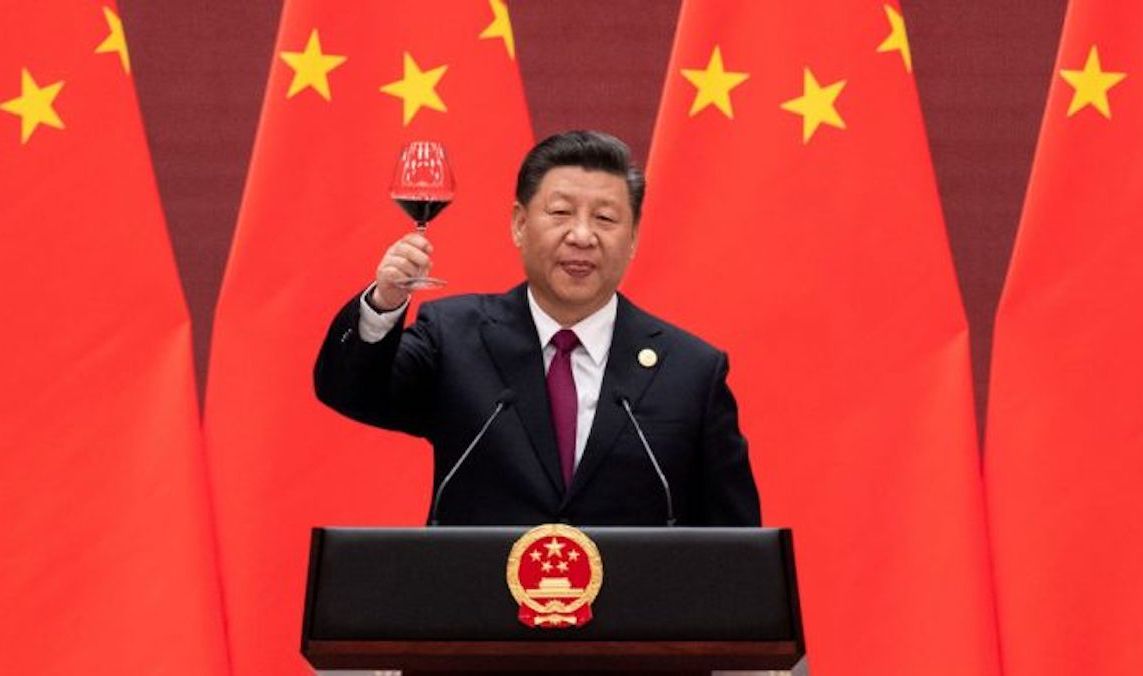

There is a huge and widening gap between reality and how the Chinese dictatorship presents reality. With the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Communist Party (CCP) approaching in July and China’s dictator Xi Jinping needing an endless run of “victories” to secure his position in advance of next year’s regime reshuffle, the state’s propaganda machine has gone into overdrive.

Likewise, the grotesque personality cult that has been built around Xi has reached new heights (or depths). In February, the People’s Daily mentioned Xi’s name 139 times in one article celebrating China’s “complete victory” in eradicating poverty. As we shall show, Xi’s anti-poverty campaign is yet another triumph of propaganda over reality. The extreme prickliness of Xi’s regime is revealed by the latest topic to be banned by internet censors: the Chinese character for “emerald” began to spread as a form of protest by Chinese netizens because it can also be read as “Xi dies twice.”

Xi faces multiple challenges at home and abroad. It is an unprecedented and possibly existential crisis for his regime and the CCP-state. This is shown by a number of new policies and pronouncements relating to “curbing financial risks” (China’s debt levels now exceed Japan’s at its highest point), fast-tracking the creation of a “fully modern military” by the year 2027 (to counter US pressure which will certainly continue under Biden), and also Xi’s overly complicated “dual circulation strategy” which aims to boost China’s consumer spending as a way to offset de-globalization and anti-China protectionist policies.

20th CCP Congress

Xi is also facing challenges from within the party-state. The key issue is next year’s 20th CCP Congress and Xi’s aim to break with traditional power limits and extend his rule for a third term – and beyond – as both CCP general secretary and president. His plan is to be ruler for life. During his first term, 2012–2017, Xi partly succeeded in quelling top-level factional power struggles by waging China’s biggest ever anti-corruption sweep. Actually this was a cover for a factionally targeted purge to eliminate his enemies and consolidate unprecedented power in Xi’s hands. As we explained the character of the Chinese regime morphed from “one-party dictatorship” into “one-man dictatorship.”

But CCP infighting has flared up again as a result of the crisis in society and in international relations. Today, this power struggle is the most severe since the period before and immediately after the 1989 Beijing massacre. While on present trends Xi will likely succeed in extending his rule, growing discontent and factional manoeuvring in the upper reaches of the party-state could force him into making compromises. The period after the 2022 Congress could see a different alignment of forces and greater intra-CCP instability. Ultimately, conflicts within the ruling class reflect social processes and the rising tide of working class discontent.

The lines of division inside the party-state are not clearly defined or settled, they are not ultimately about political ideas but about power: the CCP’s top ranks are an assemblage of capitalist oligarchs controlling vast business empires. Within these layers there is a growing pessimism that pretty much everything is going wrong.

Some anti-Xi factions are uneasy with his ultra-nationalistic and imperial “wolf warrior” diplomacy used to strong-arm other governments as shown by disputes with Australia, Canada, India and Taiwan. This section of the ruling class would prefer a return to the more discreet and pragmatic “hide and bide” foreign policy doctrine of Deng Xiaoping (“hide your capacities and bide your time”) as a means to de-escalate global tensions especially with the US.

Instead, like a frilled lizard puffing up its neck, Xi’s regime exaggerates its economic strength and global capabilities, partly as a tool of diplomacy, but more importantly still to reinforce the aura of Han nationalist “strongman” that Xi Jinping needs in order to continue ruling. China’s aggressive foreign policy – over the disputed border with India, the escalation of military exercises in the Taiwan Strait and South China Sea, the detention of two Canadian citizens in retaliation for Huawei heiress Meng Wanzhou’s detention in Vancouver – these all serve a dual purpose: to pressure foreign governments but also to feed the domestic propaganda machine.

Doubling down on repression

Another source of unease is the relentless increase in repression. This has been the most striking feature of Xi’s rule. The anti-Xi factions are hardly wishy-washy liberals. None of them would balk at ordering police to crackdown on street protests or workers’ strikes. But Xi’s brutal crackdowns in Hong Kong, Inner Mongolia and especially Xinjiang, and his default position which is to double down whenever his hardline policies meet resistance, these are becoming increasingly counterproductive.

This is for at least four reasons. Firstly, vicious repression, which in Xinjiang’s case has reached Orwellian levels, does not create “stability” which is the stated aim. Ultimately it is pushing China towards revolutionary explosions and sections of the CCP hierarchy fear this. Hong Kong’s mass democracy protests in 2019 gave a foretaste, on a local scale, of where China could be heading. Secondly, this gives Biden and other Western rulers ammunition with which to sway global public opinion and hide their Cold War strategies against China behind a narrative of “human rights” and “democracy.”

Thirdly, the tyranny of Xi’s regime has taken on a different character even compared with the past, because it is also directed internally into monitoring and policing the CCP elite. Cai Xia, a former professor at the CCP’s prestigious Central Party School (the incubator for future top officials), says China under Xi has entered an “exquisite totalitarian era” that has surpassed the totalitarianism of Mao and even Hitler. “The use of advanced technology. Strict surveillance enabled by big data. He can precisely monitor everyone. He can put you under 24/7 close surveillance,” she told Radio Free Asia (5 October 2020).

Cai, who defected to the US in 2020, is close to some of the CCP’s princelings – China’s “red nobility” – which forms the core of the capitalist class. This layer initially supported Xi, himself a princeling, but has become increasingly disaffected. Cai claims that Xi’s ruling faction, called the “Zhejiang faction” after the eastern province where many of its members built their careers, enjoys hard-core support from only around ten percent of the CCP’s officialdom at middle and higher level. The majority are unwilling to openly oppose Xi at this stage but their “support” is passive she says. While her account of the internal balance of forces may be exaggerated for factional purposes, other important developments confirm the existence of widespread but muted – we could even say “passive aggressive” dissent at various levels of the party-state.

The clearest expression of this is the increasingly open power struggle between Xi and Li Keqiang, the premier. State media, controlled by Xi’s faction, have even censored the premier’s speeches – something unseen since the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s. Since taking office alongside Xi in 2012, Li has kept a low profile. But in the past year he has become the mouthpiece of internal CCP dissent, dropping a number of media “bombshells” that constitute indirect criticism of Xi’s policies. This was the case at the end of last year’s National People’s Congress in May when Li announced to the media that 600 million Chinese, 43 percent of the population, earned no more than 150 US dollars per month. This was a reality check and a sideswipe at the overblown poverty eradication campaign that bears Xi’s official stamp.

Cai Xia’s testimony is revealing. “Other than Xi’s clan, we all know we cannot keep going like this,” she told RFA. Despite his growing unpopularity, Cai acknowledges that Xi Jinping cannot be removed by “normal” means. “Maybe an emergency of some sort or an unexpected accident could trigger explosive changes,” is her conclusion.

A fourth cause of ferment is that Xi’s extreme police state measures have the effect of incapacitating the regime’s ability to predict and deal with new crises. This was shown with devastating worldwide repercussions when the coronavirus outbreak began in Wuhan. Despite a subsequent cover up, the truth is that during the crucial weeks leading up to 20 January 2020, Xi’s regime was blindsided by the party-state’s obsession with secrecy and the actions of its security apparatus, which with brutal efficiency stamped on every attempt to sound the alarm.

China’s system is “superior”

Only the tragicomic pandemic responses of Western governments under the pressure of big business allowed Xi to shift attention and partially recover from the Wuhan episode. Wuhan was not an isolated example of government paralysis in the face of sudden crises. The eruption of million-plus demonstrations in Hong Kong beginning in June 2019, and the first trade war attacks of Trump’s administration a year earlier, are two developments that were unforeseen by Xi’s regime and were initially met with stunned inaction.

A key theme of CCP propaganda is the “superiority” of China’s (totalitarian) political system as compared to “Western-style democracy.” This is shown by the “victories” over Covid-19, China’s economic rebound in 2020, and the eradication of poverty, it claims. Similarly, China’s “vaccine diplomacy,” shipping vast quantities of Chinese made vaccines to poorer countries, is used to upstage and shame the callous stance of Western imperialism. Clearly, the deep crisis of bourgeois democracy everywhere but especially in the US, with the emergence of an unstable and authoritarian figure like Trump, has gifted CCP propaganda.

However, there is a reason why historically capitalism prefers parliamentary or “democratic” forms of government over military-police dictatorships. The downside for the capitalists is that in a bourgeois democracy the working class wins certain limited but crucial political rights: to form trade unions, political parties, its own media, and to use this democratic space to debate and clarify the ideas and struggle methods needed to fight capitalism. In a totalitarian capitalist society like China all of the above are brutally suppressed.

The capitalists in general prefer a “democratic” system because this offers a more stable form of rule. A “multiparty system” (in which all or almost all are capitalist parties) can act as a safety valve to release mass pressure. The institutions of parliamentary democracy, the press, the judiciary, contain “checks and balances” to control the ruling group and prevent it from straying too far from the interests of capital.

Totalitarian regimes by contrast, especially in an era of economic crisis and heightened class tensions, tend towards blow up and collapse. No significant section of the CCP and Chinese capitalist class favour a shift to a bourgeois democratic model. Capitalism was restored in China after the crushing of the Tiananmen Square mass democracy movement (with mass movements and strikes in more than 300 cities), but the regime of Deng Xiaoping consciously chose a path to capitalism that preserved significant state controls and rejected bourgeois democracy.

The CCP’s liberal elements at most advocate a modified dictatorship – “political reform” – with less repression and fewer political and social controls. But there are surely protagonists in the ongoing CCP power struggle who envy the US ruling class, which by means of an election were able to deal with their “Trump problem,” while for “China’s Trump” this is not an option.

100th anniversary

The 100th anniversary of the CCP will see a Niagara of nationalistic propaganda to drum home the message that without the CCP dictatorship, China is lost. But there is another side to the celebrations. They will be hi-jacked by Xi’s faction as a weapon in the internal power struggle. The personality cult will reach new levels to cement Xi’s status as the “greatest leader since Mao.” This is designed to ensure there are no slips before next year’s 20th Congress and Xi’s coronation for a third term.

The ideas that inspired the CCP’s pioneers a century ago – class struggle, anti-capitalism, democracy, internationalism and the Russian Revolution – these are all subversive topics for today’s rulers. They will be buried underneath nationalist themes like crushing “Taiwan separatism,” resisting “anti-China forces,” and realising “the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.”

With the 20th Congress in mind, Xi cannot afford any serious setbacks in the coming twelve months – no new Hong Kong-style eruptions. After a campaign of pressure in the first weeks of Biden’s term, over Taiwan, the South China Sea and the CCP’s political strangulation of Hong Kong, Beijing may attempt to ease tensions by offering cooperation at least in some specific areas such as climate change. It can’t be excluded that a limited process of détente may occur but it will be fragile and temporary. On the home front we can expect a succession of “victories” to be celebrated, all of course engineered by Xi personally.

This includes the economy. China has the distinction of being the only major economy to grow in 2020, albeit at the weakest rate since 1976. As is always the case some statistical manipulation has been used. Still, going by the official numbers, China’s economy grew by 2.3 percent last year while Germany’s contracted by 5 percent and the US by 3.5 percent.

This year, China’s GDP is forecast to expand by 8 percent, with some even predicting 10 percent growth. While that would be eye-catching, this year’s GDP data will be flattered by the low base effect from 2020. Taken over two years even growth of 8 percent in 2021 would amount to a compound rate of growth below 6 percent, a continued slowdown from 2019 (6.1 percent) in other words.

K-shaped recovery

Moreover, China has experienced a K-shaped recovery. Those earning more than 300,000 yuan (around $US48,400) per year – barely 5 percent of the population – saw their wealth increase in 2020 according to the China Household Finance Survey. But at least two-thirds of the population saw their incomes fall in real terms. According to the National Bureau of Statistics real disposable income increased just 0.6 percent in the first three quarters of 2020 over the year before. This compares to a 6 percent increase in 2019.

Household debt levels, after quadrupling in the past five years, increased to 62.2 percent of GDP in 2020. This compares to 76 percent in the US. Here, the rate of catch up is astonishing: In 2008, China’s household debt-to-GDP ratio was 18 percent compared to 99 percent in the US. More than anything this is down to the bubble in the Chinese property market, which is among the most expensive in the world. Shanghai, Shenzhen and Beijing have the fourth, fifth and sixth most expensive housing in the world, according to China Daily. Hong Kong is first.

For the first time since 2009, not a single province increased the minimum wage last year. All the indications are that this wage freeze will be extended in 2021. This explains why per-capita consumption, after adjusting for inflation, dropped 4 percent in 2020, the first such fall since 1969. The only sector to buck the trend was the luxury goods market which grew by nearly 50 percent last year. Therefore, the GDP growth achieved in 2020 was not based on stronger consumption, which is the core objective of Xi’s “dual circulation strategy,” but rather on the very factors this so-called strategy was devised to avoid: higher debt levels, greater export dependency, and a housing bubble.

Exports rose by 3.6 percent in 2020 based on the windfall effect created by the pandemic and successive lockdowns in other countries. China became the “exporter of last resort.” China’s exports of Covid-19-critical medical products more than tripled in the first half of the year, from $US18 billion to 55 billion. There was a similar surge in electronic exports and especially work-from-home products. These windfall gains are unlikely to be repeated.

More worrying is the jump in already severe debt levels, with China’s combined public sector, corporate and household debt reaching 280 percent of GDP in 2020, up from 255 percent of GDP in 2019, according to the People’s Bank of China (central bank). This rises to about 295 percent of GDP when foreign debt (which the PBoC estimates to be 14.5 percent of GDP) is included. It follows that China’s modest 2.3 percent growth was achieved by its biggest ever increase in debt. This is not sustainable. The strains in China’s bond markets, with a string of defaults by some big state-owned enterprises, points to the first serious cracks in the financial system.

Growth of left ideas

For the super-rich however, most of whom are CCP members and are integrated into the power structures of the CCP-state, 2020 saw the “fastest growth ever” according to the Shanghai-based Hurun list. China minted 257 new billionaires during the course of the year, a rate of five new billionaires every week. Their combined wealth rose by 60 percent to 4 trillion US dollars.

China “pulls away from the USA” Hurun reported, with 1,058 billionaires to America’s 696. The CCP’s 100th anniversary will see Xi’s regime performing political contortions to obscure the reality that the class character and politics of the 1920s Communists were the polar opposite of today’s authoritarian capitalist oligarchy.

The growing political radicalisation of Chinese youth, and most notably the explosive growth of “pan-leftism” and particularly “Maoism” is a troublesome potentially ruinous development for the CCP. Ironically, what we are seeing in China’s case is not conventional Maoism; rather this has become a generic term for a multiplicity of leftist ideas.

Many young Maoists in China support internationalism, feminism, LGBTQ and ethnic minority rights. These youth are deeply critical of and even oppose outright the CCP regime as a capitalist regime, although for obvious reasons such criticism is expressed in a guarded way. They have a diametrically opposite standpoint in other words to some Maoists internationally who slavishly support the Xi regime and its repressive policies in Xinjiang, Hong Kong, and against workers’ strikes.

“During the 2020 pandemic I noticed that young people in China are moving far to left,” says Liang, a supporter of ISA in China. He says the growth of anti-establishment consciousness is now widespread in society, which includes but is not confined to Maoism. “A decade ago the most vocal ideology on China’s internet was liberalism. Now the left is dominant. Just a few years ago [Alibaba owner] Jack Ma was revered as ‘Father Ma,’ now he’s called a vampire and a bloodsucking capitalist,” says Liang. Anger over the gaping rich-poor divide and especially the miserable treatment of 290 million migrant workers from China’s poorer inland provinces is a major driver of today’s political radicalisation.

Eradicating poverty

The celebrations of Xi Jinping’s “complete victory” in eradicating poverty are an attempt to shift attention from these realities. Not only has the regime proclaimed this “miracle on earth,” it has even deleted the word “poverty” from the official name of the anti-poverty agency, raising the possibility that all references to “poverty” will be prohibited in future.

Chen Hongtao, one of the editors of Maoist website Red China, was arrested in February for posting an article exposing the fraudulent nature of the poverty eradication campaign. On this topic as with many others the claims of the regime are widely disbelieved, especially by the left in China, while neo-Stalinist “lefts” internationally seem happy to swallow these absurdities.

Xi’s campaign was launched in 2013 with the express aim of lifting the remaining 100 million people out of “extreme poverty” by the end of 2020. Given that his personal prestige was invested in this enterprise there was no possibility this deadline would be missed. Reality, once again, is rewritten in the service of the dictatorship.

The government allocated 1.6 trillion yuan to poverty relief, which was used for investments in roads and infrastructure in some extremely poor regions and the relocation of 10 million people. That was one side of the story. The other is widespread forgery of data, coercion, and faking of achievements by local governments to meet their anti-poverty targets. The campaign used a very low base to define “extreme poverty” set at $2.30 per person per day. This is lower than the $3.20 per day poverty line the World Bank applies to India, and is less than half the level it recommends for an upper-middle income country like China.

Vaccine backlash

Another area where regime propaganda obscures reality is China’s fight against Covid-19. Xi Jinping declared “victory” over the pandemic at a Beijing awards ceremony on 8 September last year. This was premature and new outbreaks have since occurred. While the numbers of new infections have been low by international standards this has brought forth several large-scale lockdowns.

In Hebei province, which neighbours Beijing, more than 22 million people were ordered to remain inside their homes for more than a week in January. This was actually twice as large as the Wuhan lockdown of 2020. Similar lockdowns involving tens of millions of people have occurred in Xinjiang (July to August 2020), Jilin and Heilongjiang (January 2021). There is friction between Beijing and regional governments, some of which it believes have been too eager to impose lockdowns. This too is a feature of the intra-CCP power struggle.

Currently, the regime’s vaccine rollout is beset by problems. While China has gained some ground with its global “vaccine diplomacy,” exporting to 80 mostly low income and middle-income countries that have been cold-shouldered by the Western powers and their vaccine companies, its domestic vaccine program is going badly. China has shipped more vaccines abroad than it has administered to its own people, 46 million as against 40.5 million, according to an analysis by the South China Morning Post on February 15.

Not only does China face the challenge of vaccinating a population four times greater than that of the US, it is encountering widespread public distrust. This is because of numerous scandals involving unsafe, expired, and contaminated vaccines, drugs and food products over the past decades. Lack of transparency and the refusal of China’s vaccine makers to disclose some trial data has deepened misgivings among the public. A survey in Shanghai showed that half the population did not plan to get vaccinated. Among medical workers in Zhejiang province only 28 percent wanted the vaccine according to another survey.

The Chinese vaccines, which so far have only been approved for people under 60 years of age, have not performed well in comparisons with Western alternatives. Sinovac’s vaccine achieved an efficacy rate of just 50.4 percent in trials in Brazil, and 65.3 percent in Indonesia. This compares to an efficacy rate of 95 percent for Pfizer’s vaccine and 94.1 percent for Moderna’s (both US companies). The Financial Times reported production delays at Sinovac’s factories in China and a shortage of imported glass vials needed to store the vaccines.

Scepticism towards the Chinese vaccines has also knocked some of the shine off its global diplomatic offensive. In December, Cambodia’s dictator Hun Sen, normally a slavish CCP supporter, refused to accept the Chinese vaccines unless they were given WHO approval. “Cambodia is not a dustbin”, he said.

Although the WHO is still evaluating China’s vaccines, the Cambodian government took delivery of its first batch in January. But Hun, who is 68, had to forego his own vaccination on the advice of Chinese officials. “The safety and efficacy of the vaccine for people over 60 years old are still being studied,” he said. In the Philippines, where another authoritarian ruler Rodrigo Duterte is promoting China’s vaccines, less than 20 percent of those questioned in a poll expressed confidence in them.

Hungary is the only EU country to use the Chinese vaccines and this is of course connected to the anti-EU grandstanding of the right wing Orban government. But a survey in February showed only 27 percent of Hungarians are willing to take the Chinese shots, although among supporters of the ruling party this rose to 45 percent.

Despite its bravado, and concern that nothing should be allowed to “spoil the party” as the CCP celebrates its centenary, Xi’s regime will face a number of reality checks. The debt crisis, the continuing Cold War with the US, and fears that faster vaccine rollouts in several Western countries could tilt the scales against China, these challenges point to a turbulent period ahead. Growing discontent among workers and youth mean that new outbreaks of struggle are inevitable and that genuine socialist ideas will meet an even more receptive audience.