Serge Jordan is a member of the Committee for a Workers’ International.

On the evening of Friday, September 20, widespread protests broke out in Egypt. Hundreds of people came down to Cairo’s Tahrir Square, the epicentre of the January 2011 revolution, and many more marched through the streets of other parts of the country, including the port cities of Alexandria and Suez, as well as the working-class heartland of Mahalla al-Kubra.

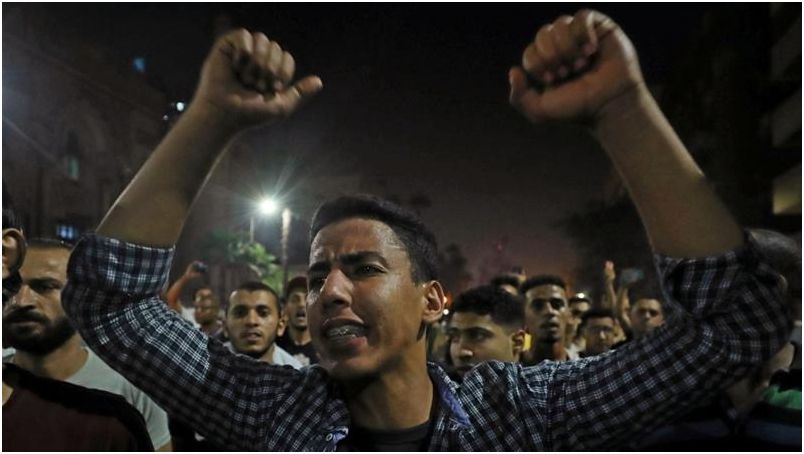

Echoing chants and slogans from the first wave of revolts that shook the Middle East and North Africa eight years ago, the protesters called for the removal of President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi and the downfall of his military regime – in some cases, destroying posters bearing the dictator’s face. This has been accompanied by the largest “electronic demonstration” in years, with hundreds of thousands of tweets calling for el-Sisi to quit.

These demonstrations have been relatively small in size so far, and it is yet to be seen whether they will morph into a larger movement. But their very eruption in a country under martial law, the risks undertaken by those taking part, the quick extension of the protests across Egypt and the boldness of the protesters’ demands, have done irreparable damage to the prestige of the regime’s figurehead and mark a decisive step in overcoming the ‘fear threshold’ imposed through years of savage state repression.

The relentless cycles of poverty-inducing cuts and attacks on living standards, coupled with the systematic suppression of the most elementary freedoms by the regime, have created an immensely explosive volcano ready to burst at any time. After taking power through a military coup in the summer of 2013, el-Sisi and his henchmen have installed one of the most brutal dictatorships of modern-day capitalism – with the political blessing of the major imperialist powers, who provide financial assistance and abundant arms sales. Some of these western arms are used by the Egyptian security forces to put down the current wave of protests.

But as Napoleon once said, “You can do anything with bayonets except sit on them.” No regime can survive for long through brutal military force alone. The fact that it faces renewed and open defiance on the streets demonstrates that even the fiercest violence unleashed by the ruling classes never provides long-term immunity against revolutionary upheavals.

Images and videos circulated on social media show that the protesters are predominantly young, often in their late teens and early twenties. The generation who actively participated in the 2011 revolution has been at the receiving end of the regime’s sweeping repression; many have been thrown in jail, killed, tortured or forced into exile. Too young to truly participate at the time, and less directly affected by the setbacks of the past decade, a new generation is now courageously coming to the fore.

Spark

The immediate spark for this movement was provided by new revelations about the corruption and obscene luxury of the ruling elite. A former actor and construction magnate named Mohamed Ali, who reaped vast profits from his contracts with the Egyptian army, published in the last few weeks a series of videos from his self-imposed exile in Spain. In them, he accused el-Sisi, his wife and senior military officials of funnelling billions of public money into self-serving vanity projects, such as the building of residential properties, palaces and luxurious hotels, and called on people to demonstrate. Some former military and intelligence officers have since substantiated similar accusations.

The top military brass’s tightening grip over the Egyptian economy and the personal concentration of power within the hands of el-Sisi’s close circle has generated grudges and frustrations among those sections of the country’s big business and military elite, which have been side-lined. The accidental figure of Mohamed Ali is a typical manifestation of these layers. But his denunciations have fuelled the rage of millions of Egyptians confronted with crumbling infrastructure and swelling poverty, unemployment, inflation and homelessness. Even the notoriously underestimated figures of the World Bank speak of 60% Egyptians now living under or near the poverty line.

The subordination of el-Sisi’s regime to the austerity plans imposed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) as a condition for a $12-billion loan package has wreaked social havoc and crushed the living conditions of working class and middle-class Egyptians. According to the government’s own figures, an additional 4 million people have fallen into poverty between 2015 and 2018. The masses have seen none of Egypt’s economic growth, praised by global pro-capitalist analysts and rating agencies. As the last days’ street protests underline a new phase of more open resistance to el-Sisi’s regime, they have also sent alarm bells through the markets. For the first time since 2016, Egypt’s stock exchange suspended trading on Sunday after experiencing its sharpest drop in years.

Regime tops confused

Since the protests a heavy security presence has been maintained in Tahrir Square. Armoured vehicles have sealed off the square and security forces have closed down cafes in downtown Cairo, in an attempt to block more protests. Hundreds of protesters and political activists have been arrested by the police, and some “veterans” of the 2011 revolution have also been targeted. Yet this did not prevent a new wave of demonstrators taking to the streets in other areas and cities across the country on Saturday, particularly in Port Said, where state forces fired tear gas, rubber bullets and live ammunition rounds. On Sunday, news came out that Facebook Messenger, BBC News and some other social media servers and local online news’ outlets had been disrupted or blocked.

Notwithstanding this, it is noticeable that the repression so far has been uncharacteristically low key, at least compared to the past standards of el-Sisi’s regime. The government’s foreign media accreditation body released a statement on Saturday with veiled threats to prosecute foreign journalists if they report events in an “exaggerated” way – but without explicitly mentioning the protests. Most national media have for their part remained largely silent.

The regime’s relative timidity in using the full force of the state so far has led some on the left to believe the protests have been orchestrated “from within”. Of course, attempts by segments of the ruling elite to divert this movement against el-Sisi for their own personal gain, and to safeguard the system they profit from, are in the nature of such situations. If the protests develop, wings of the army might decide to move against el-Sisi, as the “strongman” exhausts his capacity to ensure the ruling regime’s stability. In this sense, US President Donald Trump’s “favourite dictator” might soon become a serious liability. Hence the importance for the movement to not just target el-Sisi and his immediate entourage, but to strive to sweep away the entire rotten structure on which they rest.

But reducing the current movement to a well-orchestrated conspiracy fails to appreciate the level of genuine anger boiling underneath the surface. A 19 year-old resident of Boulaq, a working class neighbourhood of Cairo, told the New York Times: “People were just waiting for the opportunity to protest – Mohamed Ali’s videos are not the real reason why they did. The reason is that people wanted to take action.”

The regime’s lack of confidence in imposing a bloody crackdown at this point is, above all, an indication of the general state of shock, division and confusion within the upper echelons of Egypt’s state apparatus about how to react to this largely spontaneous challenge from below. Many in the ruling class certainly understand that the shedding of a large amount of blood to put the movement down could come back to haunt them: even the smallest threat to el-Sisi’s status and control of power can now quickly become an existential matter, by snowballing into a mass movement challenging the entire edifice of the regime. Above all, they fear that, not unlike in January 2011, the working-class could start regaining confidence after a long period of subjugation, and step into the fray with its own demands. On Monday, workers of Ceramica Cleopatra, a plant in the industrial zone of Suez, came out in protest against el-Sisi – on a demo their boss had organised to show support for the dictator! This episode is telling of how quickly the mood can change once the fear of the masses starts fading away.

In any case, counter-revolutionary violence remains an integral and inevitable part of the ruling elite’s arsenal in trying to scare off mass action, and protesters should be prepared to defend themselves. Committees of action in the communities, workplaces, schools and universities, can help to organise resistance against the regime’s repression, as well as to spearhead future actions on a wider and more organised level. Appeals to the many poor army conscripts with a bold program of social and economic change, and calls to create rank-and-file action committees to purge the army from its corrupt hierarchy, would fundamentally undermine both the state’s repressive capacities, and new possible manoeuvres by wings of the security and military establishment to use the state machine in order to derail the current protest movement, as they did in 2011 and in 2013.

New wave of mass struggles in the region

While it has taken quite a few commentators by surprise, the current crisis has been in the making for some time. The fear of a potential revolutionary contagion was the driving factor behind the Egyptian state’s active role in assisting the Sudanese military council in their attempted bloody suppression of the revolutionary struggle there. Instead, Egyptian protesters seem to have been emboldened by the revolution next door, which sealed the fate of Sudanese dictator al-Bashir last April – as well as by the ongoing movement that brought down ex-President Bouteflika in Algeria. As one Egyptian activist put it, “They wanted the beginning of an Egyptian scenario in Algeria…now Algeria’s scenario has started in Egypt”. Events in Egypt, if they gather momentum, could in turn fan the flames of revolt against the many oppressive regimes across the region. The recent presidential elections in Tunisia, which have seen all the favourite candidates of the ruling class, including the outgoing prime minister, heavily defeated in the first round, is yet another indication that the ruling political order imposed by capitalism and imperialism in the aftermath of the so-called ‘Arab Spring’ lies in complete shambles.

However, the recent experiences in all these countries point to a vital lesson: if the working class, poor masses and revolutionary youth are to end poverty and repression once and for all, they need to develop their own alternative based on their own parties, independent of and against all wings of the capitalist ruling elites, who will always try to hijack, divert, divide and crush revolutionary movements to preserve their rotten and exploitative system.

Mohamed Ali is an untrustworthy billionaire who has fallen out with the regime for his own personal interests. But he is right when he says that “The system is to blame” and that “We need a new system.” It was against the background of the 2008-2009 world economic crisis of capitalism that the first wave of revolutions shook the region. With a new world recession on the horizon, the problems Egyptian workers and poor are suffering will only be exacerbated, as long as capitalism continues.

A new chapter of the unfinished Egyptian revolution might be about to open. Ali has made a call for a “million march” on Friday, for students to go on strike, and for protesters to fill all major squares of the country. As a first breach has been made in the regime’s defences, this movement could well spill over, although the heavy defeats experienced by the Egyptian masses in the past few years and the inevitable scepticism about the outcome of a new revolutionary uprising will not be overcome overnight.

For this to happen, the movement needs to arm itself with a program not only aimed at overthrowing el-Sisi’s rule, but also addressing all the core questions facing the workers, the poor and their families: how to put food on the table, guarantee jobs for the unemployed youth, develop decent housing, infrastructure, education, healthcare and public transport, end the widespread sexual harassment of women and girls and so on. While fighting for free speech, democratically-run trade unions, an end to state torture and the release of political prisoners, socialists should also fight for the obscene wealth of Egypt’s ruling elite to be taken from its hands, and to be used to improve people’s lives. By repudiating the country’s debt and nationalising the big corporations, banks and large estates, starting with the corrupt military ruler’s properties and businesses, and by appealing to the millions of workers and poor to democratically manage the economy and society according to the needs of the vast majority, a new, socialist and democratic Egypt could be built, free from oppression and exploitation.