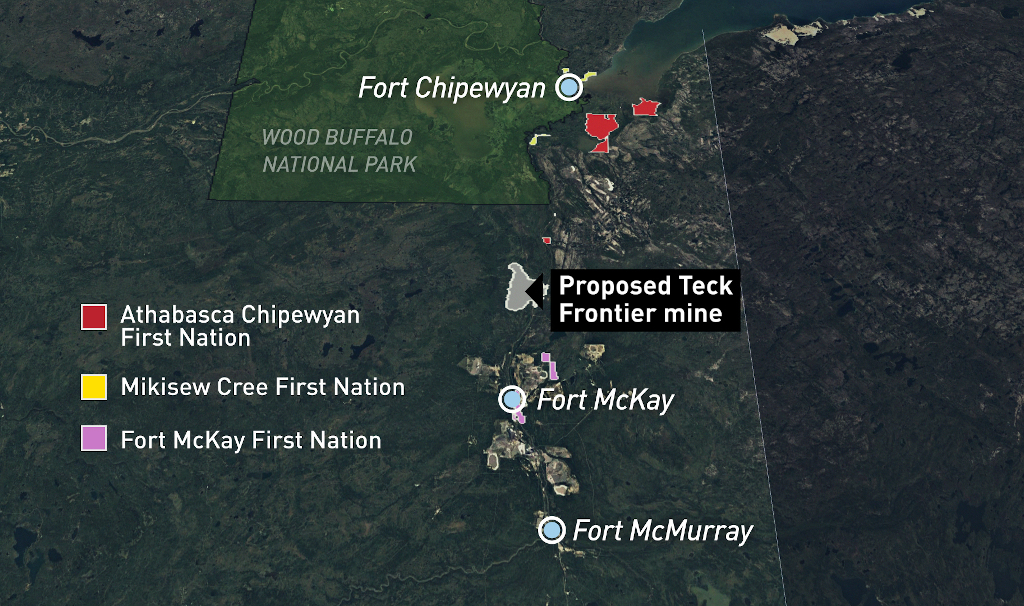

Teck Resources Limited announced its decision to remove the Frontier mine from life support on February 23, 2020. The $20-billion project had spent the whole of its nine short years awaiting a federal bill of health that would never come. Its conception promised so much, the largest tar sands project ever seen, $12 billion in federal taxes, and thousands of jobs for hard-working Albertans. Certainly, a small price to pay for the returns investors could have expected in 2011. Ultimately, however, the project was fated never to leave the nursery ward. The tragedy of the Frontier project has been blamed by Teck on an uncertain federal policy to “reconcile resource development and climate change.” Alberta Premier Jason Kenney also places blame with the federal government but sees its “weak response to ongoing pipeline protests” as a decisive factor. NDP opposition leader Rachel Notley in turn blames Kenney for “poisoning and polarizing the debate” and “undermining consensus” by attacking environmental activists and land defenders. Where does the blame lie for this tragic passing, the Frontier mine drowned, choked on its own life’s blood.

One of Many

In fact, it is unlikely that the Frontier mine would ever have been built, regardless of divisive rhetoric. Oil prices today are nowhere near what they were when the project was initially proposed nine years ago (and the industry in North America appears be entering a serious crisis), making the project seem like a widely missed bet on the part of Teck Resources. The demise of the Frontier mine is not the only recent headline to have brought fossil fuels to the fore of Canadian discourse. The sale of the Trans Mountain Pipeline expansion from Kinder Morgan to the Canadian government in the autumn of 2018 was a precursor not only to the end of the Frontier mine, but also to the national unrest over the Coastal GasLink liquid natural gas pipeline opposed by land defenders in Wet’suwet’en territory. The lack of investor confidence seen in both the Frontier mine and the Trans Mountain Pipeline is also seen in the uncertain future of another pipeline which would pump LNG from Alberta and British Columbia through northern Ontario to Saguenay, Quebec. The repression of land defenders in Wet’suwet’en territory also has direct parallels on the workers of Unifor local 594 who have been locked out of their oil refinery in Regina since December 5, 2019, and more such repression can be expected when construction inevitably restarts on the Trans Mountain pipeline. If we are to understand why the political economy of Canada seems to be so recently concerned with the contradictions of the fossil fuel industry, we will first look at the changing place of the fossil fuel industry in the Canadian economy.

The place of fossil fuels

As deindustrialization has become a widespread phenomenon in older industrialized countries thanks to chronic overproduction, the manufacturing sectors’ growth and share of GDP have shrunk. This has sent capital casting about for any profitable place to invest, and governments searching for any industry to drive growth and replace the “good jobs” and revenues that manufacturing can no longer provide. In 2018, according to Natural Resources Canada, the energy sector produced 11.1% of GDP, surpassing finance, construction, and even manufacturing. Government revenues from the energy sector between 2013 and 2017 were $16.8 billion. Oil and gas make up the largest share of the energy sector and are not evenly spread across the country. Natural gas extraction is mainly in British Columbia and Alberta, with Alberta producing roughly three times as much as British Columbia. The vast majority of crude oil is extracted from Alberta, with Saskatchewan, Newfoundland, British Columbia and Manitoba trailing far behind. While Alberta’s oil sands account for 64% of current extraction, they contain 96% of Canada’s established reserves.

The first commercial oil sands project began in 1967 and quickly lost millions. Through the 1980s a global glut of oil kept oil prices low, around $30 per barrel. It wasn’t until 2004 that prices began to rise high enough to offset the cost of technologies such as “in situ” mining and hydraulic fracking necessary to access the bitumen and natural gas underneath northern Alberta and British Columbia. Prices for crude oil peaked at over $130/barrel before crashing in 2008. By 2010 prices had recovered to $100 per barrel. Between 2009 and 2014 capital expenditures in oil and gas extraction grew from around $30 to $75 billion. When OPEC refused to cut production, the price began to drop again. Between 2015 and 2018, as oil and gas increased its share of GDP to over 7%, the Canadian oil industry lost $32 billion and capital expenditures fell 36%. A graph of Alberta’s deficit or surplus from year to year can be fairly closely mapped onto a graph of the price of oil, with a large spike in 2004, a precipitous decline in 2008, stabilizing in 2010 and again falling off after 2014. For new oil sands projects to break even, the price of crude oil needs to average $83/barrel. While most oil sands projects are designed to operate over several decades and so can absorb some short-term losses, this price has been a reality for less than ten years since the dawn of the 20th century. Simply put, in anything but exceptional circumstances, there is too much oil being produced in the world for the oil sands to actually turn a profit.

Natural gas has been heralded as a cleaner fuel that could provide a sort of bridge between coal and some future renewable energy source. Canada produces more natural gas already than it can consume. Alberta consumes the highest amount of any of the provinces, and a significant portion is used as an input into oil sands production, as a fuel for generators and vehicles, undermining both its environmental credentials and, given the numbers above, its economic viability. As prices began to rise dramatically in 2007, this, combined with advances in fracking technology, opened several unconventional resources in the United States. Unlike oil prices, natural gas prices never bounced back up after the 2008 crash. Since natural gas is a by-product of some methods of oil extraction, many producers in America have more natural gas than they can sell and have to sell at negative prices (pay someone to take it) or simply burn it off. Canada sells most of its crude oil and all of its natural gas exports to the United States. However, since the United States is also a major producer of both of these commodities, it does not need to pay a particularly high price. This is what is known as “market constraints.” Furthermore, the amount of oil produced in the oil sands has for several years exceeded the capacity to transport it. Pipelines are claimed to be the answer.

The Saguenay GNL pipeline was intended to send liquefied natural gas to European markets. When Warren Buffett pulled his company’s money out last month, the Financial Post’s headline ran “Warren Buffett’s exit from $9-billion Quebec LNG project after rail blockades ‘a signal’ to investors,” but not two months earlier they had published the headline “America Is Awash With Natural Gas and It’s About to Get Worse” in which they claimed that US producers need gas to sell at $2.50 per million British thermal units (MMbtu). The average price of natural gas in Canada in 2018 was $1.54/MMbtu. As usual the price is the signal that really guides investors. The company behind the project, Gazoduq, claims that they intend to find other funders and continue with the pipeline, but the future of the project is dubious at best.

Symptoms of overproduction

The politics of the much more notorious Coastal GasLink pipeline have been covered by us before but these numbers explain the urgency to have this pipeline built. Coastal GasLink doesn’t need to secure funding like Gazoduq, it doesn’t need to wait on approvals and court decisions like Trans Mountain, it just needs to be built. Construction has already begun and it needs to be built now to take advantage of whatever profits are left out there in Asia, especially while Chinese tariffs on US gas are in place. The brutal response of the RCMP on Wet’suwet’en territory is given more context when we understand that the provincial government is heavily invested in LNG through a series of credits to encourage resource development, given with the expectation of future royalties. Warren Buffett, Kinder Morgan and Teck were all able to back out of infrastructure projects with little to no expected returns, but given that the federal government is now even more deeply and directly invested in the Trans Mountain pipeline, we can expect a similar response to what we have seen in the past two months, especially if we see the trade war between the US and China continue.

The Co-operative Refinery Complex in Regina represents the other side of the fossil fuel industry, refining crude oil and distributing it as gasoline for consumers at a rate of 145,000 barrels/day. The refinery locked out its workers, members of Unifor Local 594, on December 5, 2019, attempting to force the union to accept concessions to its pension plan which, despite record $1.1 billion profits in 2018 for Federated Co-operatives Limited (FCL), owners of the refinery, is $71 million short of being funded. The workers responded with pickets and blockades, and the refinery used helicopters to bring scab workers into the refinery, housing them in a camp they had built the year before. The strike has seen secondary pickets, court injunctions, clashes with police, counter protesters, and arrests. While the union was largely unopposed when it was first organized in the 1940s and has not had a historically difficult relationship with the refinery, the FCL, which owns many consumer co-operatives in western Canada, has been increasingly hostile to its unionized employees. After narrowly avoiding a strike at the refinery in 2017, where the pension was also a sticking point, the FCL pushed through a two-tier wage system at grocery stores and gas stations in Saskatoon despite a month’s long strike by members of UFCW local 1400.

Amid the rhetoric from FCL about greedy strikers, and wages and pensions that are above industry norms, and the disrespectful behaviour of Unifor’s “Toronto-based leadership” a little honesty shines through. “The future pattern for fuel consumption is not looking like it’s a growth industry,” said FCL vice-president of finance Tony Van Burgsteden. In the last fiscal year, sales at the refinery fell by $430 million and net income fell $70 million. CEO Scott Banda told the Saskatoon Starphoenix that he expected the refinery to remain “competitive” in 2020 but that change in the energy market would make the refinery less profitable.

Solidarity and a Green New Deal

The Frontier mine, should it ever have been built, would have been in operation for around 40 years. While production growth projections for the oil sands are not as optimistic as they once were, recent industry estimates predict that production across the oil sands will grow to 4.25 million barrels per day by 2035. Will we really still be increasing production in 2035? The UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report showing that we have roughly 10 years to stave off the worst effects of climate change is at this point completely ubiquitous. Recently Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez have popularized the slogan of a “green new deal” in the United States. Socialist Alternative’s Kshama Sawant was re-elected to Seattle city council in October after a campaign which emphasized a municipal green new deal. Socialist Alternative Canada endorsed the Pact for a Green New Deal in 2019 and participated in their community town halls. The most skeletal premise of a green new deal is that the government should invest in publicly owned clean energy infrastructure, creating new long-term jobs, and providing retraining for workers in the fossil fuel industry. Yet given the decline of manufacturing, the fossil fuel industry, along with real-estate speculation, is the closest thing to an engine for economic growth that governments, especially in western Canada can see, and they are completely tethered to it.

The lack of confidence in the Frontier mine and the Saguenay pipeline show what the RCMP repression in Wet’suwet’en territories, the arrests leading up to the purchase of the Trans Mountain pipeline, and the ruthless tactics of the FCL in its lockout at the Regina refinery all have in common: the energy industry in Canada is as unsustainable economically as it is environmentally, and that despite this, governments are desperate to see oil and gas extraction growing. The crash in oil prices in recent weeks only reinforces this conclusion. In the first week of March the OPEC+ nations met to attempt to set production limits; when their talks broke down both Russia and Saudi Arabia drove production up to the hilt. At the end of February, Western Canada Select, the price indicator for crude oil coming out of Alberta, was trading around $40/barrel, already too low, but since the first week of March it has fallen to $10/barrel. Now there are reports that, rather than nationalizing this failing industry and steering it towards a useful end, the federal government is preparing a bailout package in the billions.

The dispute at the refinery centred around pensions, and while workers should always struggle for the best possible working conditions and compensation, the aims of the labour movement must ultimately transcend fighting for good jobs in an industry that is simultaneously dying and killing the planet. In the not so distant past this was understood by Local 594 itself. Before a series of mergers brought it under the umbrella of Unifor in 2003, Local 594 was affiliated with the Energy and Chemical Workers Union (ECWU). This union understood that organized labour needed to push for progressive energy policies and in 1980 they produced a National Energy Policy, which included not only taking large sections of the fossil fuel industry into public ownership but a plan for a transition to a renewable energy system through conservation and investment in renewable energy. Sadly, history has since shown that no level of Canadian government ‒ municipal, provincial, or federal ‒ will willingly walk away from the fossil fuel industry: it must be taken from them. Accomplishing a green new deal in Canada will require a mass movement, but more than this, it will require solidarity between Indigenous land defenders like the Wet’suwet’en and a labour movement that recognizes that its real long term interests are inseparable from those of the land defenders.

After Local 594 clashed with police, where 13 picketers were arrested in January, they called out to Canada’s other large unions saying, “We are calling on the broader labour movement to send activists to this line. This is one of those moments, let’s be really clear, one of those moments where workers are under attack.” In a glimpse of what a real labour movement might look like, leaders of several large national and provincial unions sent donations and representatives to the Unifor rallies and picket lines. When the RCMP raided Wet’suwet’en territory in February, several unions sent letters and statements in support, but when solidarity blockades sprang up across the country only the ILWU refused to cross the lines of the blockades. These two struggles have significant differences that cannot simply be dismissed in calls for solidarity. The workers at the refinery are highly skilled and well paid. They are fighting to defend jobs that will ultimately have to stop being done in an industry that must ultimately disappear, while the Wet’suwet’en are struggling for sovereignty on their historic territory and for their historic form of self governance. Only by recognizing the real differences and oppositions can we then see where the actual basis for solidarity lies. What the refinery workers and the land defenders share is the experience of having court injunctions handed down against their blockades and pickets, police forcefully dismantling their blockades, and mass arrests of peaceful picketers and land defenders. At the root of these shared experiences is that both struggles threaten the shrinking profits of the fossil fuel industry, which can live only by their defeat. It is on this basis that the solidarity necessary to win a green new deal can be built.