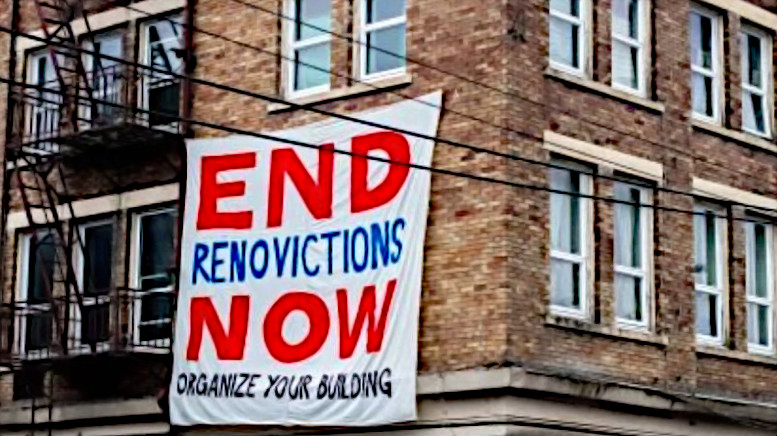

Renovictions, when landlords feign the need for renovations to evict tenants and jack up the rent, are a fundamental part of why housing is so unaffordable in Canada. Regulations governing rent increases vary from province to province, and the pandemic has brought some temporary rent freezes. In non-pandemic times, BC, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia and PEI have yearly caps on rent increases determined by government guidelines, generally below 5 percent. There are no rent controls in Alberta, Saskatchewan, New Brunswick and Newfoundland and Labrador.

What all provinces have in common, and what is driving up rents – on top of the lack of publicly owned low-rental units – is the absence of rent control laws, which fix rents on the unit (called vacancy control). This means landlords can push rents up sky-high between tenants. This gives landlords a big financial incentive to evict tenants for spurious reasons, which they do.

However, in BC it just got a little harder for landlords to evict tenants so they can push up the rent. Effective July 1, landlords must apply to the Residential Tenancy Branch (RTB) with all permits and approvals to prove that their planned renovations can only be completed if the tenant moves out. Only with the RTB’s approval can a landlord evict a tenant.

The new law aims to discourage landlords from making disingenuous renoviction attempts by adding a layer of bureaucracy that should catch meritless renovictions. Landlords must give the tenant the right of first refusal to move back into the rental unit once renovations are complete. Meanwhile, tenants may dispute the application and must receive four months notice if the landlord get RTB approval. After all this, landlords still have to prove that the renovations occurred. They can’t just change a lightbulb, get a new tenant and increase the rent by $300.

But wait, can landlords still jack up a tenant’s rent after a renovation? Yes, they can. If landlords can prove to the RTB that additional rent increases are needed to recover some of the renovation costs, they can increase the rent an additional 3 percent per year for 3 years. So, the rent could go up by 9 percent plus inflation over 3 years. This measure is meant as a trade-off, to encourage landlords to invest in maintaining their properties in good condition, but also prevent astronomical rent increases.

New Westminster goes further

The BC NDP’s rental law reform is welcome but is long overdue and falls short of a New Westminster city bylaw restricting renovictions. The NDP’s Rental Housing Task Force submitted its final report in late 2018, but the NDP rent cap, limiting it to inflation, and the renoviction reform came 2.5 years later. New Westminster, a small city in Metro Vancouver, has over 9,000 aging purpose-built rental units, in 300-plus buildings, representing over 60 percent of the rental supply. In the years leading up to the creation of the provincial Task Force 315 tenants were renovicted in New Westminster. Faced with the housing crisis, New Westminster Mayor Jonathan Coté decided that his city could not wait any longer for the NDP to act. City staff started to look at alternatives, and the city adopted a bylaw restricting renovictions in early 2019.

Like the RTA reform, New Westminster’s bylaw requires landlords to apply for an additional rent increase beyond the yearly permitted amount. However, the bylaw is the strongest protection against renovictions in Canada because it goes further, requiring landlords to provide alternative accommodations for the tenant, if they receive city approval to have the tenant vacate the rental unit during renovations. The bylaw recognizes that landlords have an obligation to provide housing and that renters still have a fundamental need for housing during a renovation. Failing to provide proof of the need to relocate a tenant, failing to relocate a tenant or implementing large rent increases can now result in fines of $500-$1,000/day and they could lose their business licences.

In April 2021 a BC Court of Appeal upheld the legality of the New Westminster bylaw after a two-year court battle with a private company trying to evict all residents from a 21-unit building. This key victory showed that cities do have the right to make bylaws taking on the housing crisis. In a way this victory also chips away at a 1974 BC NDP decision to move the regulation of tenancy disputes from municipalities to the provincial RTB. Since the bylaw was adopted, there have been no unjustified renovictions according to the City of New Westminster.

Since the court decision, municipalities across Canada have contacted the City of New Westminster, hoping to implement similar bylaws.

Of course, the housing crisis is not only due to renovictions. It also stems from decades of failing to build low-rent social housing, rampant speculation, low-density zoning, a lack of rent control on the unit and a lack of progressive property taxes. The RTA reform is definitely a welcome brake on renovictions in BC, but it is disappointing that the NDP’s reform falls short of the work done to protect renters in New Westminster. Mayor Coté recognizes that making unjustified renovations more difficult helps to curb renovictions but admits that it alone does not solve the housing crisis. The City is also looking at incentive packages like tax exemptions that encourage both investment in buildings and increasing housing density.

Of course, landlords and developers are opposed to low-rental units. They want desperate people to pay exorbitant rents. In a typical comment, David Hutniak, CEO of Landlord BC, maintains that the heart of the housing crisis is a “chronic shortage of purpose-built rental housing.” But tearing down older buildings with modest rents and replacing them with expensive units for rent or sale adds to the problem, not solves it.

Will the RTA reform and the New Westminster bylaw put an end to all renovictions? In a word: no. While they do make renovictions more difficult, the economic incentive to renovict is still in place. The BC change leaves the decision up to the RTB, a body notorious for favouring landlords, with tenants only winning 13 percent of appeals. A recent case of a tenant in Oak Bay, who was evicted because she was $1 short on her rent payment for the past six months due to a bank charge, illustrates the extreme bias of the RTB.

Rents can be increased massively when a tenant moves out, so gentrification, a part of the housing crisis, can continue. BC needs a vacancy control law to effectively stop renovictions. It would place a cap on rent increases between tenants. In other words, tie rent increases to the rental unit, not the tenant. Building fighting tenants’ unions, supporting progressive city councillors and building a movement in the streets can win vacancy control in BC and across Canada.

The most needed action is a Canada-wide mass program to build affordable rental housing. The Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation recommends that housing costs should be no more that 30 percent of income. This is the baseline for genuine affordable housing.

The mass program to build affordable rental housing needs to be created by the public sector, not the private sector. As the 2021 CCPA report How to build affordable rental housing in Vancouver demonstrates, new non-market units can have break-even rents covering upfront construction costs and the cost of this housing over time. Most importantly, these rents would be much lower than that of newly built market rental housing. Non-profit rental housing built on city land can offer rents 43 to 49 percent lower than those of for-profit rentals, equaling differences of $600 to $1,300 per month!

Mobilizing to Fight the Housing Crisis

Municipalities are on the front lines in fighting the housing crisis. Campaigns can win major victories in cities and thereby put pressure on provincial and federal governments to act. In Seattle, Socialist Alternative’s city councillor Kshama Sawant has built a movement to make the city more affordable. In 2015 she was instrumental in passing a rental protection law making it illegal for slum landlords to increase the rent if their units aren’t up to code. In 2020, Sawant’s Tax Amazon campaign fought hard and won a tax on major corporations that will raise $210-240 million a year, creating tens of thousands of green union jobs by building permanently affordable city-owned housing.

Here in Canada, Socialist Alternative campaigned together with the Vancouver Tenants’ Union for vacancy control laws. We also went all out to get COPE’s Jean Swanson elected to Vancouver City Council. COPE’s campaign included a demand to create a progressive property tax on mansions to fund construction of city-owned affordable housing. Significantly, Swanson’s campaign in 2018 pushed the NDP to restrict the allowable rent increase for 2019 to the rate of inflation, not including an extra 2 percent on top of this. Socialist Alternative Canada continues to campaign for a progressive property tax in Vancouver and more recently in Surrey.

Housing should not be a commodity. To truly put an end to the housing crisis in Canada, Socialist Alternative calls for a mass program to build and renovate decent, safe and affordable public housing run by tenants’ democracy. We need to protect renters and homeowners from housing speculators by increasing taxes on corporate and wealthy speculators. Increases in land value due to planning and infrastructure changes should benefit the public, not private owners. Ultimately, we need to place into public ownership big developers, major construction companies and corporate landlords.