Boris is a member of Linkse Socialistiche Partij / Parti Socialiste de Lutte (ISA in Belgium).

Failure of the Mitterand government

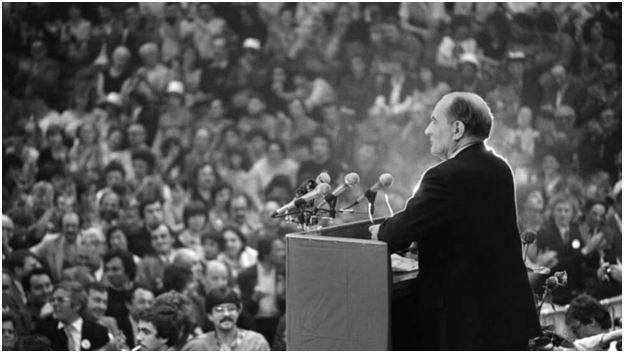

May 10, 1981. In Paris, 200,000 people gathered at the Bastille, shouting for joy. Scenes of jubilation burst out in all the cities across France. François Mitterrand had just won the second round of the presidential election with 52% of the votes. For the first time in the history of the Fifth Republic (established in 1958), a left-wing president had been elected. Expressing the bosses fear, the right-wing daily Le Figaro wrote the day after the elections: “Marxist-inspired collectivism is now at our doorstep”.

Coming to power

François Mitterrand had been a minister 11 times under the Fourth Republic (1946-58). He was not a revolutionary, but understood how the events of May 1968 had deeply radicalized the workers. When he took over the leadership of the brand new Socialist Party (PS) in 1971, he set it on the path of an electoral alliance with the French Communist Party (PCF) which, by curbing the strikes of 1968, had demonstrated that it could stay within the limits of the system.

In 1972, the Union of the Left was formed around a joint program bringing together the PS, the PCF and the Movement of Left Radicals (MRG). Reflecting, although only going part of the way to meet the post 1968 radicalisation, their program called for social reforms and the nationalisation of nine major industrial and credit groups. This led the bosses and the rich to fear the worst, especially as the capitalist crisis of 1973-4 broke out shortly after. Factory closures and massive layoffs followed one another, a new phenomenon appeared: mass unemployment. Between 1974 and 1981, the number of unemployed tripled to one and a half million.

Unfortunately, the joint program was not used to help build forces for struggle. On the contrary, the PS, the PCF and the trade union leaders used it to put all hope on an election victory for the left. Thus, in 1978-79, when a four-month workers’ revolt broke out in Lorraine and Nord-Pas-de-Calais against the dismissal of 21,000 steelworkers, Mitterrand simply promised, once elected, to reopen the closed steel factories. The steelworkers would pay dearly for disbanding their struggle.

In the 1976 and 1977 elections, the PCF was overtaken by the PS. Wishing to regain its position as the leading left-wing force, the party left the Union of the Left, justifying its departure by saying that the program did not promise to nationalize enough companies. In the ranks of the workers’ movement, where there was a strong desire for a change in policy, the PCF’s zigzag policy was poorly perceived while the PS was seen as the party of left unity.

1981-1982. A Keynesian policy and capitalist sabotage

Mitterrand’s 1981 election platform was a program for economic recovery based on public investments, including the creation of 150,000 jobs in public services, major public works, construction of social housing. It called for an increase in purchasing power, the introduction of the 35-hour week to combat unemployment and the redistribution of wealth through a tax on the fortunes of the richest. The PS of the time went even further by defending the nationalisation of nine major industrial, credit and insurance groups. However, there was no question of a socialist transformation of society.

After winning the second round of the presidential election, Mitterand’s government, which included four PCF ministers initiated a series of reforms by hiring 55,000 civil servants; increasing the minimum wage by 10%, family and housing allowances by 25%, the disabled allowances by 20%; abolishing the death penalty; repealing the anti-squatting law; legalizing 130,000 undocumented migrants through work; introducing a tax on large fortunes; increasing the budgets for housing, culture, employment and research by between 40-500%; freezing prices; nationalizing the top 36 deposit banks as well as Paribas, Suez and 5 major industrial groups (CGE, PUK, Rhône-Poulenc, Saint-Gobain, Thomson); introducing the 39-hour week and a fifth week of paid holidays; reducing the pension age to 60; introducing new labour legislation; capping rents and repealing the offence of homosexuality.

The government launched a Keynesian policy – promoting economic recovery through consumption and investment – but the exceptional period of prolonged post-war economic growth was over. Since the mid-1970s, capitalism had been in crisis. The United States had entered a recession and Germany’s economic slowdown had a profound impact on the French economy. The country was in the midst of stagflation: an economic recession combined with galloping inflation.

The government did everything in its power to convince the bosses of the merits of its recovery policy in order to restructure French capitalism and strengthen its competitive position. But the capitalists wanted to crush the hopes of the workers and therefore organised sabotage of the government’s policy.

With the crisis, capitalists lost confidence in their own economic system. They preferred to invest their money in speculative investments, which experienced a large growth at the time. The state had to step in by replacing capitalist investment with public investment in nationalized companies. As the government wanted to respect the legal framework rather than rely on the action of the workers’ movement, the right-wing and the bosses seized the Constitutional Council, asserted the right of private property and extracted 39 billion francs from the State in compensation for all the nationalisations. Some bosses were rubbing their hands: with the crisis, their previous losses were also compensated.

The nationalized banks were quickly confronted with the restrictions placed on their operations by the laws of the private market. Their cheap credit policy failed to boost private investment while the French Franc was under attack from the markets. The Banque de France tried to keep the latter afloat by using foreign exchange reserves. Between 1981 and 1983, the franc was devalued three times. Inflation undermined the effectiveness of measures to improve purchasing power. The trade deficit (imports over exports) grew sharply. The Banque de France blocked the provision of more liquidity and forced the government to borrow on the private market. All this was accompanied by a capital flight of an unprecedented magnitude: large fortunes were fleeing taxation.

Many rich people crossed the Swiss border with suitcases or garbage bags filled with silver and gold hidden in spare wheels. Foreign capital also left. Exchange rate controls were introduced and border controls tightened, but remittances to Switzerland continued.

‘Austerity turn’

Very quickly, the PS-PCF government backed down. A 4-month wage freeze took place in June 1982, followed by the abolition of automatic wage indexation. The PCF denounced this turn, but its ministers did not question their support for the government. The bosses applauded: the left had succeeded without the slightest resistance to do what the right could only have hoped for.

March 21, 1983 was the “turning point” when Keynesian economic policies were abandoned in favour of neoliberal monetarism. The PS and PCF decided that France should remain in the European Monetary System (EMS). To reduce deficits, the Delors’ plan of austerity was introduced.

In March 1984, PCF ministers participated in a final major attack: the loss of 21,000 jobs in the state owned steel industry, the same number of job losses as under the right-wing government of 1978-1979. 150,000 workers demonstrated in Lorraine, but the march to Paris organised by the trade union leaders was more like a funeral procession. The failure of the PS-PCF government to fight unemployment and save the steel industry was complete. In the June 1984 elections, the National Front obtained 11% of the vote, its first breakthrough at national level. The PS fell to 21% and the PCF to 11%. The PCF left the government, and would never regain its position in its former workers’ strongholds.

The failure of reformism, not socialism

This failure occurred at a time when Thatcher in the United Kingdom and Reagan in the United States were confronting the working class to permanently change the relation of forces in favour of capital. It opened the way for four decades of brutal neoliberal policies. Since the “austerity turning point” of March 1983, the PS’s participation in power in France, but also in Belgium and elsewhere in Europe, has been limited to applying neoliberal policies. This failure is not the failure of socialism, it is the failure of reformism.

In 1986, Henri Emmanuelli, former SP minister summarized his opinion on the shift of March 1983: “The Socialists had long dreamed of a third way between socialism and capitalism. Obviously, it was no longer possible. The solution is to clearly choose one of the two systems and correct the excesses. We have chosen the market economy.” France lacked a revolutionary party rooted in the workers’ movement that did not limit itself to a reform program but linked the struggle for reforms with the overthrow of capitalism to replace the market economy with a democratically planned economy.