Kermit the frog used to sing: “It’s not easy being Green. It seems you blend in with so many other ordinary things and people tend to pass you over.” That wouldn’t be a bad characterization of the Green Party of Canada.

The Greens have just elected a new leader, Annamie Paul, the first Black woman to lead a mainstream Canadian party. Her victory, following the election of Jagmeet Singh as NDP leader in 2017, means that two of the five parties in the House of Commons have people of colour as leaders. This is shift from the historic domination of politics by white men, which reflect Canada’s changing population and attitudes.

While her victory has produced some excitement, reflected in her improved vote in the by-election held in Toronto Centre, the Green vote dropped in York Centre to 2.6 percent, the other by-election that day. Her failure to get elected means the Greens have the dilemma of a leader without a seat in Parliament, an issue that caused difficulties for Singh.

However, the policies of a political leader are the decisive test: will they make change? Previous women leaders have not always made big improvements. Some, such as Margaret Thatcher, were a disaster for women and all workers. Barack Obama as the first Black president of the US generated huge excitement and hope but failed to tackle racist policing or Black poverty. To help understand Paul’s likely impact it helps to examine the Green Party’s actions in Canada and internationally.

Origin of the Greens

Although the Greens have some progressive policies, they are a pro-capitalist party, which limits their ability to deliver their policies. Their political dilemmas go back to the origins of green parties. As is often the case, the movement on the streets had a major influence on political outcomes. The 1960s and early 1970s were a significant time, not just for the environmental movement. It saw major radicalizations, particularly of young people, around civil rights, anti-war, anti-colonialism, gay rights and the emergence of the feminist movement. There were also major labour struggles and strikes.

This period also saw the growth of a politically less party-affiliated middle class, expressing themselves in the 1970s as “citizen’s movements.” They cared, for instance, about nuclear power plants or the militarization coming from the arms race. They were met with ignorance and arrogance by the powers that be, including the traditional left parties, and so were pushed to look for alternatives outside the existing centre and left parties. European social democratic parties, exemplified most in Germany, had created the notion of “social partnership” between labour and capital to minimize strikes and social unrest in general as long as there was enough growth so that labour could get its share of growth.

Had the traditional social democratic parties been genuine, activist, socialist parties, they would have been the ones to which the young green protesters gravitated. For example, those participating in the recent Greek protests against the gold mines initially turned in the main to Syriza, the left-wing governing party from 2015-19. One of the many results of the Syriza leadership’s capitulation to the demands of the troika and global capitalism was a betrayal of these environmental protesters.

Policies and tactics

The political goals of the green movement focused on changing government policy and promoting environmental social values. Prominent examples included protests in the US and western Europe against nuclear power development; the related decades-long controversy surrounding uranium mining in Australia’s Northern Territory; protests against deforestation in Indonesia and the Amazon basin; moves to protect “wilderness” and countryside; and campaigns in several countries to limit the volume of greenhouse gases released through human activities.

There were differing strategies of these environmental movements. Some were self-consciously activist and unconventional, involving direct-protest actions designed to obstruct and to draw attention to environmentally harmful policies and projects. Greenpeace, which uses direct action, was founded in Vancouver in 1971. More mainstream groups’ strategies included public education and media campaigns, community-directed activities, and conventional lobbying of policy makers and political representatives. In all this, a major weakness of the Greens was their lack of a class approach exhibited in a failure to understand the interests of workers, e.g. loggers, who might not be convinced of the importance of giving up their jobs to preserve old-growth forests. Also, many environmental groups ignored urban environmental issues, and the interconnection between poverty and environmental degradation and pollution. The most polluting industries are usually located in poor neighbourhoods. In the US, in particular, this also involved racism, with sites in Black and Indigenous communities.

When the green parties were formed, they were conceived of as a new kind of political organization that would bring the influence of the grassroots environmental movement directly to bear on the machinery of government and make the environment a central concern of public policy. The world’s first green parties were founded in the early 1970s. The first explicitly green member of a national legislature was elected in Switzerland in 1979; later, in 1981, four greens won legislative seats in Belgium.

Globally, protests became more common from the 1970s on, demanding action on climate change as a whole, or opposing specific assaults on a local environment. These included the hundreds of thousands who demonstrated in Germany, against the Stuttgart railway project, the movements against gold mines in Greece, the anti-fracking protests in a whole number of countries, the protest against the sinking of Greenpeace’s Rainbow Warrior by the French government or the demonstrations against nuclear power (“no nukes”) in several countries.

Greens in government

“Now let’s vote for ourselves” was one of the slogans of these days, as green parties and electoral alliances entered the scene, and right from the beginning were quite successful. While green parties may often be perceived as both the best fighters in defense of the environment and as being on the left on social issues, their record in government tells a different tale.

The most successful environmental party has been the German Greens, founded in 1980. It won representation in the federal Bundestag (parliament) in 1983 with 5.6 percent of the national vote. In 1987, this increased to 8.4 percent. In 1998 it formed a governing coalition with the Social Democratic Party (called red-green), and the party’s leader, Joschka Fischer, was appointed as the country’s foreign minister.

This exposed the tensions within the German Greens between the Fundis (fundamentalists) and the Realos (realists). While the Realos were in favour of moderate policies and government cooperation, the Fundis opposed joining a coalition government. The Realos opted for pragmatism and were more willing to sacrifice green principles and make compromises with other non-green parties. The Fundis, more decentralist and left wing, included eco-socialists in their ranks. Eco-socialists hold that capitalism is the primary culprit behind the ecological crisis because of its insatiable pursuit of profit through an economic system that is powered by climate-altering fossil fuels.

Two of the core policies of the German Greens were opposition to nuclear power and militarism. In the 1998-2005 coalition, the Greens supported the first international deployment of German troops and a long delay to phasing out of nuclear power. The Realos abandoned core principles as soon as they were in government – their idea of being realistic, is having no principles!

In 2003, the red-green coalition presided over the introduction of the Hartz IV laws and €1 jobs – the biggest attack on welfare and workers’ living standards since the second world war.

It wasn’t only in Germany that the greens in government supported anti-working-class policies and abandoned their principles. In France, the Greens took part in a coalition with the Parti Socialiste, along with others, from 1997 to 2002. Securing the environment ministry, the Greens effectively abandoned their opposition to nuclear power. Over five years, the “plural left” government privatized more than previous conservative governments. Air France and Air Inter were privatized, and the national rail company, SNCF, was partly dismantled.

In Ireland, the Greens joined a coalition with Fianna Fáil and promptly acquiesced to Shell Oil getting permission to develop the Corrib gas field off Ireland’s west coast. The Irish Greens accepted other measures that they had campaigned against in opposition, including the use of Shannon airport by the U.S. military for “renditions” – the forced removal of suspects to secret locations for interrogation and torture. The Greens initially signed up to the EU/IMF savage austerity, including the household charge, water charges, VAT hikes and major public spending cuts, only belatedly pulling out as their poll results reached vanishing point.

All of the governments in which greens have participated have been in the age of neo-liberalism and have – to a greater or lesser extent – overseen privatization, deregulation and attacks on workers’ rights.

Slow growth of Canada’s Greens

In Canada, the growth of the Greens was slower than that of their European counterparts, with two factors inhibiting their electoral influence:

- The fact that the NDP throughout this period, and beyond, remained the official party of opposition and dissent – the NDP, unlike the German SPD, was “untainted” by never having been in government at a federal level or being seen to have betrayed the hopes of green protesters.

- The Canadian election method of first past the post made it difficult for the Greens to achieve significant electoral gains as their support is spread thinly across many constituencies, with few concentrated areas of support. In most European countries the system of proportional representation means that with a minimum percentage (typically 5 percent) of the vote, a party gains representation in parliament.

The Green Party of Canada was officially founded in 1983 and the party ran 60 candidates in the 1984 federal election, winning only 0.2 percent of the votes. As with other mainstream parties in Canada, the peculiarities of the different provinces in terms of history, political culture and economic development have also determined the fortunes of the Greens in these provinces and Canada wide.

The Greens have grown steadily in federal elections. From a small start in 1984, by 2004 they won 4.3 percent and by 2008, the party won 6.8 percent of the popular vote, attracting nearly 280,000 new votes. In 2011, Elizabeth May was the first and only federal Green MP, elected in BC’s Saanich-Gulf Islands. She was re-elected in 2015. A by-election in the BC riding of Nanaimo-Ladysmith in May 2019 was won by Paul Manly. In the 2019 federal election, both May and Manly were re-elected and Jenica Atwin was elected in Fredericton, New Brunswick, taking the party to three MPs.

Greens also have elected representatives in New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Ontario and BC. In BC they held the balance of power from 2017 to September 2020.

Greens in BC

After the 2017 election in BC, the Green Party agreed to support the NDP minority government, on the basis that it had better environmental policies than the BC Liberals.

Socialist Alternative wrote a review of the Green’s support of the NDP government in an article on the 2020 BC election:

“The results have been woeful. The NDP promised to use ‘every tool in the tool-box’ to stop the Trans Mountain Pipeline, yet has used very few, mainly a court case, and Greens have shown no more imagination … The Greens voted against the massive Liquid Natural Gas export plans that relies on fracked gas, which includes a large taxpayer subsidy and will destroy BC’s climate change targets. However, it was passed with Liberal support and the Greens did not use this coalition of NDP and Liberals to embarrass the NDP.

“In the last election the NDP said it would review the Site C dam, its main purpose to supply cheap power to liquefy natural gas. When the government decided to go ahead, the Greens did speak against the dam but pledged not to defeat the government. Now the dam, which has costs spiralling out of control, could bankrupt BC Hydro. On both LNG and Site C, the Greens talked ‘no’ but took no action.

“The Greens did dig in their heels to stop some NDP policies, including staunchly opposing making it easier for workers to unionize. So, the Greens are firm anti-worker but weak on the environment.”

The Greens also have three councillors in Vancouver. In theory, progressives should have a majority on council with the Greens and with two more left councillors, including Jean Swanson and a former NDP MP as Mayor. Yet as some Greens vote with the right wing, after two years, the policies from council are only progressive in words, with little or no action on homelessness, protecting renters, building social housing, controlling developers or taxing the rich.

“Not left or right but forward”

In 2019, the federal Greens launched their climate action plan, named “Mission Possible,” as the centrepiece of their program. It boasts of “mapping a course to a post-carbon, prosperous and safe world.” Like many political party programs, while good on aims they lack any strategies for implementation. They say they’ll slash greenhouse gas emissions by 60 percent by 2030, which certainly outdoes the Liberals and the NDP (who have a 38 percent target).They say they’ll end all fossil fuel industry subsidies (same as NDP). They’ll give incentives to Canadians to retrofit their homes and prompt entrepreneurs to develop green technologies (same as NDP). In suitably vague and wordy fashion, they promise to “implement a bold Canadian climate and energy strategy that includes robust plans to build and sustain the green economy.”

To implement “Mission Possible” the Greens would “Establish an inner Cabinet, akin to the Second World War ‘War Cabinets’ to ensure we take partisan politics out of the fight for our survival.” This indicates the main problem with the Greens – a classless approach to politics that fails to recognize that the problem at the root of the climate crisis is capitalism and a ruling class that is determined to protect their system. Bringing together “men and women of good will” from the Conservatives, Liberals, NDP and Greens may sound dramatic and appropriate for a crisis of this gravity but if the edifice of capitalism remains, so too will the crisis. The Greens’ political weakness was epitomised in the last election with their slogan “not left or right but forward.” If you’re neither on the left nor on the right, you are placing yourself in the middle of the road. And if that’s where you are, it doesn’t matter if you’re moving forward or backward, you’re going to get knocked down by traffic from both directions.

Leadership challenge from the left: Eco-socialism

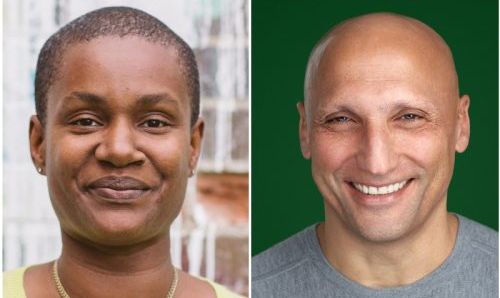

Elizabeth May resigned as Green Party leader in November 2019, thus requiring a leadership election that took place online, finishing on October 3. There were eight candidates with two front runners: Toronto-based international affairs expert Annamie Paul, the establishment/continuity candidate (with tacit support from May), and Montreal lawyer Dimitri Lascaris, representing the left-wing challenge and a self-described eco-socialist.

Nearly 35,000 Green Party members were eligible to cast votes in the recent leadership race, as party membership grew from 22,000 at the end of the 2019 federal election, with most joining during the leadership campaign.. One in three of the party’s members live in Ontario, and one in four live in British Columbia. In the last Green leadership race, in 2006, fewer than 3,300 people cast ballots. This time, 23,877 Green members cast a ballot – a 69 percent turnout.

Annamie Paul’s policies largely continue the policies of the Greens in recent elections. However, Paul, like other mainstream Greens, imagine this fair and environmentally healthy society can be achieved while profit-driven corporations dominate society. The Greens, with Paul’s leadership, will continue to occupy a political space between the NDP and Liberals, a greenish policy with some progressive policies, based on capitalism. This has trapped the Greens in an in-between place, yo-yoing between four and seven percent of the popular votes since a jump in the 2004 election to 4.3 percent.

Dimitri Lascaris’ campaign aimed to move the Greens to the wide-open space on the left. His distinct policy generated energy, and many new recruits.. Unfortunately, it was not enough to defeat the establishment candidate who, prior to the vote, had benefited from the party machine’s actions in undermining the campaigns of both Lascaris and Meryam Haddad, another candidate running as an eco-socialist, by having them disqualified for a time during the election campaign. In every round of the exhaustive ballot Lascaris was second, but never managed to pick up enough votes to overtake Paul.

Tensions had been building within the Greens for some years – the main dividing line being over eco-capitalism or eco-socialism. The left-right divide is not unique to the Canadian Greens. So, what did the Lascaris eco-socialist challenge consist of? His program is very detailed with items ranging from ATM fees to RRSP tax shelters, with the section on the environment covering 14 pages. He states: “It is time for an eco-socialist approach because, without democratic socialism, we cannot protect the environment. The climate emergency is a condemnation not of humans, but of ecologically destructive capitalism.”

Most of his proposals are excellent and he rightly pointed to the inability of capitalism to tackle the ecological crisis or provide economic justice. However, when considering ownership and planning, he uses the vague terms of “socialization” and “stakeholders” rather than nationalization combined with democratic workers’ control to map out the goals: “Socialization will create publicly, cooperatively or collectively owned and democratically run productive units governed not by profit but social and ecological goals set by stakeholders. We must distinguish it from nationalization, which has typically created crown corporations functioning no differently from their private counterparts. Socialization will be directed, first and foremost, at taking large corporate extractive concerns into public ownership.”

His economic plan: “This plan will implement a just, green and egalitarian economy under social control rather than under the control of the profit motive. It will equalize opportunities to contribute and to benefit.” For all the good things Lascaris proposed (free public transit in cities, a national program for social housing, implementing capital controls to prevent capital flight to tax havens) he passed over how the economy will be removed from the control of the profit motive. Furthermore, although there is talk of stakeholders and transformation, there is no mention of the working class as being one of these stakeholders. Like many on the left, he argues for a basic income (minimum guaranteed income) to deal with social inequality. This is a dangerously deceptive road to walk down as it could end up exacerbating inequality.

A Lascaris victory could have split the Greens as most of their elected representatives – MPs, provincial members in MLAs in BC, Ontario, New Brunswick and PEI, and councillors – are on the eco-capitalist wing of the party.

A new party for Canadian workers

While the Green Party contains many good individual activists, we don’t believe that the Greens are the organization that will either solve the climate crisis or offer a path to the socialist transformation of society. Dimitri Lascaris is to be congratulated in raising socialist ideas within the Greens and coming as close as he did in the leadership election. Many of the new recruits to the Greens, enthused by Lascaris’ platform and campaign, will be planning to stay and keep fighting for their ideas. At the same time, there will be others who decide to look for a socialist alternative elsewhere.

Socialist Alternative raises the idea of a new workers’ party, although recognizing that it is not a likely prospect in the short-term. A workers’ party is much more than a coming together of various small left groups. It will require new forces taking to struggle, especially youth and workers. This would likely include both the left wing of the NDP and the eco-socialists from the Green party. We said in our Canadian Perspectives document of 2017:

“The key features of a new party are that it is involved in struggle and does not limit its program to what capitalism demands, even if it is not explicitly socialist. Socialist Alternative would argue for a party that is federal in structure, allowing affiliation of unions, socialists, environmental, Indigenous and other organizations. The party would campaign, not just during elections, but continuously on the many issues people face. The party’s life would combine activism, political education, cultural activities and solidarity. We envision a party that is rooted in communities and grassroots organizations, with strong democratic rights and controls. One of its purposes would be to contest elections, and we would propose that all elected representatives would be responsible to the party and only paid the average wage of a skilled worker.”

If you are interested fighting now for people and planet and in the future to build a new workers’ party join Socialist Alternative.

Correction, November 11: Unfortunately we made a mistake in the number of people Lascaris’ campaign recruited to the Green party. Total membership of the Greens increased during the leadership campaign by around 10,000, rather than Lascaris’ campaign recruiting 10,000. We have corrected this and revised that section of the article.