Vincent Kolo is a contributor to chinaworker.info.

After the short-lived Wagner revolt in Russia on June 24, Xi Jinping’s regime reaffirmed its support for Putin, describing Russia as China’s “comprehensive strategic partner of coordination for the new era.” But Xi’s regime is clearly shaken by these events. For almost 24 hours, as Yevgeny Prigozhin’s mercenary forces marched towards Moscow, the Chinese media said nothing.

The CCP regime is not blind to the precarious position of its allied ‘strongman’, a year and a half into Europe’s biggest war since 1945. It sees that the political costs of Russia’s war in Ukraine are mounting. But what is also clear is that Xi has little choice than to stay the course and reaffirm their “partnership.” The Chinese dictator has invested heavily in this alliance and will not lightly abandon it. Russia, for all its evident weakness, is China’s only ally that is a major military and nuclear power, and a veto-wielding member of the UN Security Council. Pitted against the world’s still dominant military power, US imperialism, with its array of alliances now re-energized by Putin’s war, the Chinese regime needs all the allies it can get.

The China-Russia axis is therefore a crucial part of the international architecture of the new Cold War. It is a decisive component of the Chinese regime’s strategy to fight US-led economic and military containment. Yet the significance of the alliance with Russia is sometimes underestimated, not least because Xi’s regime consciously employs false signalling as part of its diplomatic toolbox. Of course, Chinese diplomacy is not unique in that respect — all capitalist governments make use of such techniques to hide their real aims.

The “no limits” partnership between Xi and Putin is not a formal military alliance, nor is it ever likely to be. That would be out of character for the CCP. However, that does not mean there is no military element to this alliance. A key consideration for Xi’s regime is the role Russia could play in the event of a future war over Taiwan.

One of the most important strategic benefits of close China-Russia ties, which predate by many years the February 2022 declaration of a “no limits” partnership, has been the security of China’s 4,200-kilometre border with Russia to the north. This has allowed the CCP to focus southwards, on building up and modernizing its navy in particular — now the world’s biggest — to counter the US-led military build-up in the South China Sea and Taiwan Strait, and also to deter India and Vietnam (both supported by the US) in respect of border and maritime disputes. The quid pro quo is that Russia has been able to shift the vast majority of its military resources to Ukraine.

Pro-Russia propaganda

The Chinese regime’s so-called peace plan for solving the Ukraine war, which it does not even call a war, is a good example of the CCP’s use of the art of misdirection. Does the Chinese proposal, and the sending of “peace envoy” Li Hui to Kyiv and other European capitals, indicate a shift by Xi’s regime or a divergence with Putin that undermines their alliance? The answer is no. It merely shows the Chinese regime’s ability to throw dust in people’s eyes.

From China, ISA supporter Wu, makes the following comments: “The Foreign Ministry is always claiming that it stands on the side of justice and peace, and actively promotes peace talks and so on. This kind of empty statement at first glance is sometimes very confusing, and even makes people mistakenly think that the CCP is trying to withdraw from the Sino-Russian alliance; but compared with the diplomatic rhetoric, domestic media’s internal propaganda better shows the Chinese regime’s real position in the conflict.”

Wu explains that China’s state-controlled media is wholly on the Russian side in the war. It repeats what are common propaganda points for both regimes: that NATO and the US are responsible for the war by threatening Russia’s security, and that Ukraine is a puppet of the West, which has combined to fight Russia. He cites the commentary by China’s main Xinhua news agency on the Wagner mutiny. This type of language rarely leaks out to the outside world, where the Chinese regime wants to be seen in a different light.

“[T]his incident has proved Putin’s ability to control the situation,” the commentary states. “At present, Russia is still fighting with the entire West. During the difficult period of fierce battle, no matter how reasonable Prigozhin’s appeal was, he also made a big and untimely mistake. There is a high degree of consensus among all parties in Russia — the current response to Western provocations is the main direction of attack.”

Therefore, even in the CCP’s attempts to explain away a highly embarrassing crisis, it stresses that the fight against “Western provocations” is fundamental. Xi’s regime can repeat Putin’s propaganda because it overlaps with and reinforces its own Cold War agenda against the US-led bloc. The CCP needs to mobilise mass opinion in China behind Xi’s political course of turning China away from its former economic dependence on US and Western capitalism, a Chinese version of “de-risking.” His regime is convinced, and correctly so in this case, that the Cold War struggle will only escalate and is therefore attempting to sanctions-proof the Chinese economy. Already, the trade, financial and technology restrictions imposed on China by the US and its allies, unconnected to the Ukraine war, have inflicted serious damage on the economy. An open military confrontation between the two sides is not excluded in the future. This is the catastrophic logic of capitalism and imperialism.

Disastrous reverses

China’s domestic media coverage has not shifted an inch in its pro-Russia and pro-Putin stance since the first day of war. At first sight that is a somewhat incredible fact given the series of disastrous military reverses suffered by the Russian side and the way this has played into the hands of US imperialism. But there is a method to Beijing’s “madness.” The CCP’s aim is to use Russia’s conflict with Western imperialism as preparation for coming conflicts of its own.

“The Chinese media is almost the mouthpiece of the Russian media” explains Lin, another ISA comrade in China. “All news about the war comes from the Russian satellite network (Sputnik) and Russia Today (RT). China’s online censorship almost exclusively targets pro-Ukraine information, while allowing pro-Russia media to create rumours.”

The fact that China’s state media only has one reporter in the warzone, underlines its complete dependence on Russian media reports, says Lin. “The single reporter is Lu Yuguang of Phoenix Satellite TV. Last year, this reporter also created fake news, editing video footage of car repair enthusiasts to make a video allegedly showing Ukrainian HIMARS being destroyed by the Russian army,” he tells us.

From this we see clearly how different is the Chinese regime’s propaganda towards its own people, with a total pro-Russian bias, from the image it tries to project externally. Xi’s regime employs deliberate subterfuge on the Ukraine war (as do other imperialist governments) to obscure its real aims and more effectively defend its own interests.

Naturally, socialists cannot base our analysis on what the capitalist governments say. Even less on speculative media reports or rumours about possible schisms between allies. It is necessary to look at the actual balance of forces internationally and the strategic interests of the ruling classes in each case. This is the only way to orientate ourselves correctly, to develop perspectives and to warn of the dangers ahead.

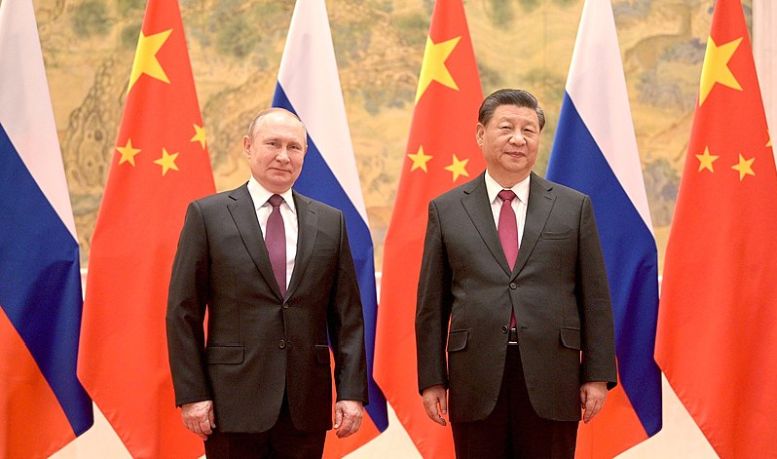

Xi Jinping in Moscow

Xi’s visit to Moscow in March this year has been misread by some commentators, who see signs of Chinese discontent with Putin as its main takeaway, and draw the conclusion from this that the China-Russia alliance is under pressure. There can be tensions, but these don’t change the fundamental dynamics. Xi’s regime is less than delighted with the utterly shambolic conduct of the war by Putin’s army. This came as a shock to Beijing, which had an inflated view of Russia’s military capabilities. This has even caused the CCP to re-evaluate some of its prior calculations regarding a war to “reunify” with Taiwan, although Xi has definitely not abandoned that long-term objective.

But Xi’s visit to Moscow this year was his first overseas visit since 2020, due to the pandemic. Prioritising Putin (who Xi has met 40 times) over other governments was a very conscious signal of the importance of their alliance. Xi used his Moscow visit to reaffirm, in the face of increasing Western pressure, China’s support for Putin’s regime. This support has been extensive, while stopping short of direct military support or openly defying the Western sanctions. That would risk incurring sanctions against China’s economy.

The war and the US-led sanctions against Russia have given China an unexpected economic boost. Bilateral trade between the two countries increased by 40.7 percent in the first five months of 2023, compared to the same period last year. This included a 75.6 percent increase in China’s exports to Russia. For Putin’s regime, China has been a lifeline, which also partially explains why original predictions of a complete economic collapse in Russia have not materialised. Russia’s GDP fell by 2.1 percent in 2022, not the 12 percent contraction predicted by the World Bank.

Over the same period (January-May 2023), China’s trade with the US shrank by 12.3 percent and with Taiwan by more than 25 percent. This economic shift is not an unimportant factor, and neither of course is China’s access to Russian hydrocarbons at discount prices, reducing its dependence on seaborne deliveries that could be blockaded in a military conflict. But for Xi’s regime the strategic alliance with Moscow goes beyond economics. What drives the China-Russia alliance is the overarching pressure — economic, political and military — from the US-led bloc.

Protecting Putin

This means their alliance is unlikely to break down as long as the two regimes remain in power. The CCP has drawn the conclusion that Washington now seeks regime change in China as a key objective of the Cold War. Russia’s value to the CCP is therefore in a “united front” to undermine the US-led Cold War strategy. This united front could of course collapse under the impact of major events, military defeat and revolution, as could its Western equivalent. But it is unlikely to be brought down by secondary setbacks.

Xi Jinping clearly has the strongest hand in this relationship, with Putin and the Russian state getting weaker the longer the Ukraine war goes on. China is of course using this imbalance to its advantage, to nibble away at Russia’s traditional dominance in Central Asia for example, and to extract further economic benefits. But at the same time Xi is forced to do everything in his power to protect Putin’s regime, in economic and diplomatic terms, if not at this stage with direct military support.

The Wagner mutiny horrified Xi’s regime, especially given certain historical parallels with the end of Gorbachev’s rule and the break-up of the USSR in 1991. It is important to note that at beginning of Xi’s reign, he insisted that all CCP officials study the collapse of the USSR, to stiffen them in their resolve to defend the dictatorship. Xi, in his characteristic patriarchal language, attributed the USSR’s collapse to the fact that “nobody was man enough” to prevent it.

Even after the Wagner crisis further eroded Putin’s power, Beijing declared its continued support because as Frederick Kempe of the Atlantic Council put it: “Even a much-weakened Putin is better than no Putin at all for Xi.”

The nightmare scenario for the Chinese regime, which it wants to prevent at all costs, is the collapse of Putin’s regime and its replacement by a regime hostile to China. Although not a likely development at this stage, this would upend the current international balance of forces to China’s detriment. Paradoxically, this also means that while Putin is clearly in a weakened position post-Wagner, the fear of “what comes next” gives him some extra leverage with Xi Jinping.

China’s “no limits” partnership with Putin was announced on February 4, 2022, from the stage of the Winter Olympics in Beijing. It is extremely unlikely that Xi was unaware of Putin’s plan to invade Ukraine, as we reported at the time. How much he knew or actually understood is a different question. But the “no limits” partnership and its timing obviously helped Putin to launch the invasion. To claim that the Chinese regime played no part would be laughable. This created splits in the CCP at the time, as we also reported. Anti-Xi factions within the regime, which were weak and have since been roundly purged, were alarmed that his very public rebranding of the alliance with Russia (it wasn’t something completely new) was a provocation towards the US and Europe. This was just the latest of many “wolf warrior” own goals, they believed, when China’s severe economic situation warranted more caution.

Xi pushed ahead, even when Russia’s setbacks in Ukraine gave evidence of a major miscalculation. This is because he sees no alternative. Abandoning the alliance with Russia would not strengthen but decisively weaken his regime’s position, and would not lead to any significant de-escalation of the conflict with the US, rather the opposite.

Wolf warriors out

But after further consolidating his control over the state at the CCP’s 20th Congress last October, Xi took measures to ditch aggressive “wolf warrior” rhetoric and rephrase his foreign policy in more skilful, less nationalistic language. As we explained, this did not represent a strategic shift, only a tactical one. We made the comparison with US imperialism’s diplomatic upgrade under Biden, compared to the bombastic and counterproductive approach of Trump’s administration. Fundamentally, Biden has only continued and built upon the Trump era anti-China strategy. And Xi is doing the same in the post-wolf warrior era.

One example of this tactical change of tone is Beijing’s 12-point so-called peace plan for Ukraine. This was launched on February 24 this year (the anniversary of Putin’s invasion) and the timing was not coincidental. Armed with this entirely fraudulent “plan,” Xi was able to go to Moscow and reaffirm his strategic alliance with Russia while at the same time blowing smoke in the face of assorted governments and political commentators. Some read this proposal to mean that China is distancing itself from Putin and wants to end the conflict, possibly even exerting pressure on Putin to make territorial concessions. But this is not the case.

Xi’s regime above all wants to avert a full-blown Russian defeat, which could endanger the alliance with China and the survival of a pro-China regime. The so-called peace plan repeats glib, typically CCP phrases about respecting the sovereignty and territorial integrity of all countries, but doesn’t explicitly say it supports Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. Nowhere does the document call for the withdrawal of Russian forces or even use the word invasion. The title of the document is “China’s Position on the Political Settlement of the Ukraine Crisis” — even here adopting Kremlin terminology.

The Chinese position is to freeze the conflict with a ceasefire, meaning that Russia’s territorial gains would stand. The document further protests the West’s “unilateral sanctions” and its “Cold War mentality” — two key issues for the CCP. It offers China’s assistance for post-conflict reconstruction in Ukraine, hoping to win contracts for Chinese construction companies.

Could China’s plan work?

Xi’s regime is not deluded enough to believe this “peace plan” will be taken up in any significant way. Its aim is to obfuscate, to create a diplomatic fog that allows Beijing to protect its alliance with Putin, work to prevent a crushing Russian defeat, and give it a tool to deflect pressure from European and other governments. So far, this has not met with any real success.

It is not completely excluded, although not very likely, that if the Ukraine war drags on for a long time, the Chinese regime might be approached by the Western camp to be part of a negotiated settlement, to use its good agencies with Moscow to get an agreement.

This would not represent a real solution because on the basis of today’s intractable capitalist crisis any such “peace” imposed by outside powers would be fragile. Beijing’s idea, that it could act as a guarantor along with European powers for Ukraine’s future security on the proviso of course that Ukraine does not join NATO (Russia’s condition) is a non-starter. US imperialism, which is the decisive force on the Ukrainian side, will not simply stand aside allowing Beijing to significantly strengthen its position in Europe.

Much has been made of Xi’s phone call to Ukraine’s president Zelensky in April, but this does not suggest a shift in China’s policy. This first contact between the two leaders since the start of the war came more than a month after Xi’s meeting with Putin in Moscow. It also came after China’s ambassador to France Lu Shaye, an unreconstructed “wolf warrior,” sparked a fresh diplomatic crisis between China and the EU with his televised remarks stating that former Soviet countries such as Ukraine and the Baltic states don’t have “effective status in international law.”

Lu was not recalled or even reprimanded by the Chinese government. This incident is the equivalent of the deliberate use of mixed signals by the US administration, when Biden repeatedly (on four occasions) made ‘gaffes’ stating that the US would intervene militarily in any conflict between China and Taiwan.

China’s premier Li Qiang has just completed a European tour as part of Beijing’s charm offensive to undermine the cohesion of the Europe-US bloc, and to coax increasingly wary European capitalists back to China. This was not a great success as shown by the European Commission, on the final day of Li’s tour, issuing its annual strategy report, which stresses the need to cut back “strategic dependencies” on China. Days later, Beijing at the last-minute cancelled a planned visit by Josep Borrell, the European Commission’s Representative for Foreign Affairs. No reason was given for the snub, but it is likely to be in retaliation for the decision of the Netherlands government just days earlier to further tighten its ban on sales of semiconductor manufacturing equipment to China, in accordance with demands from Washington.

China faced further setbacks with the German government finally aligning with the US position to ban Chinese companies Huawei and ZTE from the country’s 5G network. And Italy’s far-right Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni is threatening to pull the country out of China’s Belt and Road Initiative. In 2019, when Italy became the only G7 country to join the BRI, this was a major diplomatic coup for Xi’s regime. But times have changed. The process in Europe of governments strengthening their links to the US and NATO continues. This does not mean they have exactly the same interests, but as with the China-Russia bloc, the ruling classes feel there is no alternative.

The new Cold War is an expression of the bankruptcy of global capitalism. Neither of the two imperialist blocs offer any way forward. The logic of this conflict is towards further escalation, more militarism, nationalism, state repression, and a fragmented global economy that will enormously sharpen class contradictions. Both blocs are heading irrevocably towards deepening economic and political turmoil. The task of socialists is to expose the role of the imperialists on both sides and to assist the workers’ movement to achieve a political reboot by building a strong international socialist alternative.