Humanity is at one of the most important crossroads in its 200,000 year history. Having spread across the globe about 30,000 years ago, we advanced through various stages of hunting and gathering to develop agriculture and animal husbandry 20,000 years later. This began a shift from human muscle power to animal muscle power as our primary source of energy. But it is only in the last 300 years that another massive shift has taken place: from animal power to fossil fuels – coal, oil, and gas – which dovetails precisely with the rise of industrial capitalism.

Humanity is at one of the most important crossroads in its 200,000 year history. Having spread across the globe about 30,000 years ago, we advanced through various stages of hunting and gathering to develop agriculture and animal husbandry 20,000 years later. This began a shift from human muscle power to animal muscle power as our primary source of energy. But it is only in the last 300 years that another massive shift has taken place: from animal power to fossil fuels – coal, oil, and gas – which dovetails precisely with the rise of industrial capitalism.

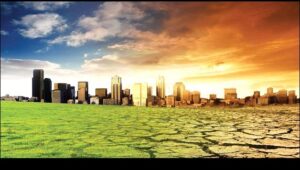

This period has seen an explosion of technological progress, economic output, and world population. Yet the carbon-emitting basis of this impressive run, combined with the rapacious individualism of competitive (and later monopoly) capitalism, now clearly threaten all advances made with an impending and ever-more palpable environmental catastrophe. For many, this ominous threat calls into question whether ‘industrialization’ was ever such a good thing in the first place.

A Dual Crisis

At the same time as we reach the heights of this ecological crisis, a social crisis is becoming increasingly obvious to all: the failure of capitalism to make good on its promise of raising living standards and bringing about freedom from daily drudgery. Instead of ‘rising standards,’ workers have seen stagnation or major declines, despite the fantastic income growth for a tiny elite. Instead of ‘freedom from feudal drudgery,’ daily life is increasingly consumed by mind-numbing busy-work: filling out forms, making calls to settle endless bills, commuting hours to work, buying groceries, picking up kids/loved ones, etc. This is in addition to the experience of work itself, which is increasingly made as meaningless, monotonous, and tenuous as employers can get away with. The financial collapse of 2008 and the ensuing world recession are only the most recent signals of such slow-burning decay.

Given these predicaments, it is fair to say that humanity faces a dual crisis: massive inequality and stagnating growth on the one hand and an ecological nightmare on the other. Some would argue that the two problems — in addition to police brutality, gender oppression, war in the Middle East and Ukraine, etc. — are separate and distinct, requiring ‘individual’ analyses and piecemeal solutions. From a socialist perspective, however, both crises flow from the exploitative logic of capitalism. ‘Exploit workers’ is the first imperative of a system designed to squeeze value from the labor of others; ‘exploit nature’ is the second, heeded by firms seeking low costs for the material for production, as well as the disposal of refuse produced by production.

The solution, therefore, to both crises is the replacement of capitalism with a rational, planned, and democratic economy — otherwise known as socialism. But how exactly would this work? While a growing number of Americans, particularly those under 30, show an interest and openness to socialism, there remains considerable confusion as to what it would actually look like. In this article, Socialist Alternative spells out as clearly as possible the key features of socialism, how these differ from the deformed structures of the Soviet Union, and how such a system could immediately be used to stop global warming.

Public Ownership

The defining feature of socialism is public ownership of the main economic resources. These include major corporations such as Wal-Mart, Exxon-Mobil, General Motors, and Apple which are currently publicly traded, but are effectively owned and controlled by tiny cliques of investors. Economic resources, however, include not only factories, inventory, production technology, distribution networks, and infrastructure, but also money capital, overwhelmingly concentrated among a small number of banks — Goldman Sachs, J.P. Morgan, Citigroup, Bank of America, et. al. These would also be taken into public ownership.

But what is ‘public ownership’? This is the key distinction between socialism and capitalism. Under capitalism, most of society’s resources are owned and controlled by private firms which carry out their function (be it production, distribution, financing, or services) for one reason: to create profit for its owners. GE, for example, is ostensibly an ‘electrical equipment manufacturer’ but in 2013 reaped more than half its profit from financial operations — lending money at interest — rather than from the production and sale of goods (GE 2013 Annual Report). This shows how the goal of capitalist organizations is not to produce goods or services per se, but to produce profit. How they achieve this — be it by making and selling quality products, by mass producing shoddy ones, by monopolizing scarce resources, or by lending out money — is a secondary question.

In contrast, publicly owned enterprises can operate within a much longer timeframe and even at an economic loss. Their primary goal, if properly administered, is to produce products and services that meet social needs. They do not have to make profit (or surplus), and if they do, this can be reinvested to expand that enterprise or start new ones. With the majority of firms under public ownership, the door would be open to large-scale cooperation, coordination, and a drastic reduction in waste.

Democratic Control

A keen observer might say that although public ownership sounds good, its actual practice in the Soviet Union was highly inefficient and often yielded inferior goods. Socialist Alternative would not dispute this. The difference, however, between the command economies of the Soviet Union, Maoist China, and others and the planned economy we advocate is who is doing the planning. Any complex social system requires feedback. Under capitalism, this is imperfectly provided by consumer ‘choice’ (though many markets, particularly for utilities and housing, offer few real choices).

In a socialist economy, the planners and decision-makers would not be an elite caste of state officials, as they were in the Soviet Union after 1923, but elected representatives of workers and consumers, empowered to express rank-and-file needs and correct any shortfalls. This also distinguishes the public enterprises we’re fighting for from the existing, top-down ones, such as urban public school systems. In every workplace, school, hospital, and neighborhood, daily oversight would be in the hands of working people organized into councils to facilitate direct democracy. Local (e.g. workplace), councils would then elect delegates to larger bodies that could manage entire enterprises in coordination with each other and consumers’ councils. To prevent careerism and bureaucratic behavior, all delegates would be paid no more than an average workers’ wage, be subject to frequent re-election and immediate recall.

Sound like a lot of work? Council-based democracy would indeed require time and effort from all participants. But this would be all the more possible given a drastic reduction of work time. Capitalists currently make profit by squeezing every last drop from some workers while relegating millions to unemployment or under-employment. By providing jobs for everyone, we could easily reduce the workweek, eliminating both unemployment and overwork. When no one has to work more than 30, 25, or even 20 hours a week, there will be ample time left for leisure, self-education and grassroots democracy.

To be clear, council democracy is not something dreamed up by Marx, Engels, or any other theorist. It was invented by workers in the course of struggle — first in the Paris Commune of 1871, then again in the Russian revolutions of 1905 and 1917, later during Germany’s 1918-19 upheaval, and, in a smaller form, during the 1934 Minneapolis general strike. In each case the dysfunction of capitalism and workers’ strike action forced communities to devise alternative ways of administering society. Only in Russia 1917 did this lead to the wholesale overthrow of capitalism.

Internationalism

The third component of socialism is internationalism. Capitalism long ago created a world division of labor, international trade (including that of enslaved people), and structural inequality between countries. Socialism could not turn back the clock and build a durable economy “in one country”—a prime reason for the decline of the Soviet Union. It would necessarily utilize the existing global infrastructure of production and distribution and wield it, but rather than to make profits for elites, it would be used to meet human need equally while eliminating reliance on fossil fuels and scorched-Earth resource extraction.

Indeed, the environmental crisis demands a global response. Low-ball carbon emissions “targets” and so-called “cap-and-trade” policies do little more than shift fossil-fuel usage (and blame) around the world without actually reducing emissions. The competitive structure of profit-driven capitalism stymies the ability of individual countries or firms to take meaningful action: much like the conundrum of the Cold War, each profit-driven body fears that if they “disarm” from fossil fuels, others won’t, and they’ll be left at a disadvantage. Removing profits via public ownership and democratic control at an international level is the only way to make possible a massive redirection of investment.

Redirecting Investment

The sheer volume of wasteful and harmful spending under capitalism boggles the mind. At any given time, human societies have only a finite quantity of wealth to invest. The environmental sustainability of such investments provide a basic measure of an economy’s efficiency and long-term prospects; today’s global capitalism, on this measure, scores very poorly.

To start, $20 trillion worth of untapped fossil fuels are currently claimed as assets by big energy companies and traded on “futures” markets. This sum is equal to 40% of the global GDP. The emissions that would result from burning such “reserves” are well beyond what scientists believe would trigger irreversible climate change, resulting in millions of deaths and millions more being forcibly displaced. Capitalism, quite literally, is invested in social destruction.

But there are many other ways in which current spending is wasteful and indirectly harmful insofar as it withdraws resources from useful, sustainable channels. Advertising, for instance, is a $140 billion industry in the U.S. (Kantar Media 2013) which produces absolutely nothing useful — it simply persuades people to buy things they don’t need or to buy one brand of necessary thing over another. Yet the sum of money devoted to this in the U.S. alone is three-and-a-half times what the U.N. estimates as the global cost — $41 billion — of providing the world’s population with housing, food, healthcare, and education. Add to this the trillions spent on national “defense” and weapons production — products solely designed to kill people — widespread use of planned obsolescence by electronics and machine manufacturers, and the subsidization of auto-dependent suburban sprawl, and we start to get a picture of the resources capitalism pours into ecological dead-ends.

A publicly owned and democratically controlled economy would provide an immediate mechanism for redirecting investment. Millions of good jobs could be created almost overnight by rebuilding energy efficient housing and transport, retooling factories to produce the needed materials, and harnessing renewable energy through wind farms and desert-based solar plants. And the needed technology already exists. In 2009, professors Mark Jacobson and Mark Delucchi published a plan to power society on 100% renewables by 2013, arguing that a “sustainable world” is “technically possible” (Scientific American November 2009).

Room for Creative Initiative

One common objection to socialism, or large-scale public ownership, is that it would stifle creativity, innovation, and individual initiative. This is simply not true. Public ownership would only be necessary for those mega-corporations and banks that already control the global economy. These organizations are, right now, large, impersonal bureaucracies that strongly discourage worker and consumer input. Socialism would simply democratize and coordinate these massive institutions, giving workers and consumers a real voice in how they are run.

But beneath the mega-companies of the global economy, small businesses could coexist alongside consumer and community cooperatives. There is simply no need to ‘nationalize’ the local pizza joint, auto repair shop, or convenience store. The only difference would be that anyone employed at such enterprises — as well as every other member of society — in addition to being guaranteed a living wage, would also receive quality housing, healthcare, education, and childcare for free, since such necessities would be considered human rights, not commodities. Furthermore, the freeing of individuals from overwork, endless bureaucracy (paying the bills, etc.), long-distance commuting, and fear of financial ruin — all endemic under capitalism — combined with the active provision of accessible education and leisure facilities would unleash untapped potential for personal growth, creativity, and innovation.

Break with Reformism and the Democrats

The big question hanging over all of this, of course, is how to achieve it. Many in the environmental and economic justice movements hold out hope that Democrats will eventually push through reforms that could snowball into meaningful change. Unfortunately, it is increasingly obvious that this is simply not the case. The Obama administration has established itself as a committed ally of big oil. Recently, it approved searches for oil and gas beneath the Atlantic Ocean, and has previously supported hydraulic fracturing (fracking), oil drilling in the Arctic and guaranteed major loans for nuclear energy development (despite the Fukushima disaster). Only in the face of mass protest and civil disobedience has Obama delayed his decision on the Keystone XL pipeline, which would bring resource-draining Canadian tar sands oil to the Gulf Coast. In general, leading Democrats have flagrantly ignored and actively worked against environmental justice, despite paying it ritualized lip service to garner votes.

In the end, facts speak for themselves. There is no time to waste in taking serious action against climate change. As shown above, capitalism is deeply committed (to the tune of 40% of the GDP) to fossil fuels and a wasteful economy based on planned obsolescence and worker exploitation. In order to address the dual crises of climate change and inequality — to redirect investment towards renewable energy, green jobs, and durable goods production — we have to bring the largest corporations and banks under public control. This requires taking them out of private hands and running them in a democratically planned fashion. And although this process will likely start in one country, it must become international. This, in a nutshell, is what we mean by ‘socialism’: a world economy controlled by workers and consumers and devoted to the needs of humanity rather than the narrow interests of investors. Humanity is indeed at a crossroads — and capitalism is in the way. We urge all members of the 99% to join in the struggle for system change to stop climate change.