Per-Åke Westerlund is a member of Rättvisepartiet Socialisterna (CWI in Sweden).

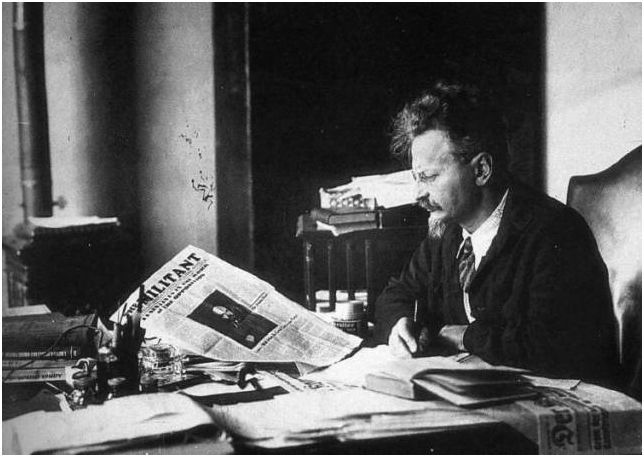

Leon Trotsky’s In Defence of Marxism is a book every Marxist needs to study. It’s a collection of letters and key documents from a sharp debate within the Socialist Workers Party in the US in 1939-40.

It’s a very rich book, on application of Marxist theory in a rapidly changing world – Stalinism in the Soviet Union, fascism in power in Italy and Germany, and World War II. In parallel, it concretely deals with building a revolutionary party – orientation to the working class, party democracy and internationalism. One thing is evident all through the book, Trotsky was not a “Marxist” who just repeated old formulas and he was not afraid of admitting mistakes.

World War II of course was a test for every organisation and individual. Bourgeois politicians internationally had already in big numbers capitulated to fascism as their only way to crush the working class and achieve revenge against the Russian Revolution.

In August 1939, just before the outbreak of the war, workers and most others were stunned by the announcement of the Hitler-Stalin pact. It was a desperate move by Stalin, who had failed to get the alliance with France and Britain that he wanted, to avoid an immediate attack by Nazi-Germany. When that inevitable military assault came, in June 1941, Stalin initially did not believe the news.

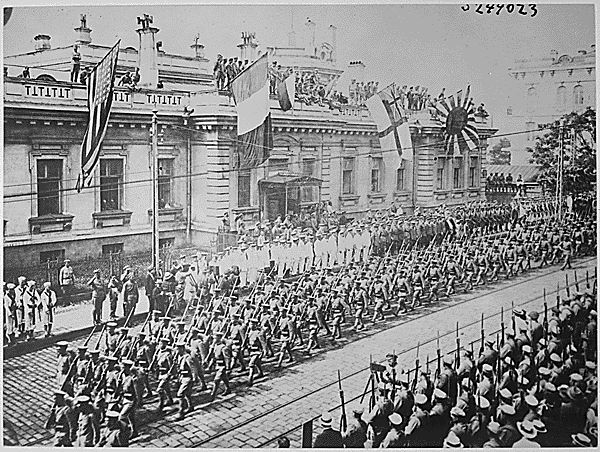

The pact changed the propaganda of the Communist International, focusing on criticism of British and French imperialism instead of Nazi Germany. Militarily, the pact meant that Poland was invaded from West by the German army on 1 September, followed by an invasion from East by the Soviet Union in mid-September. Soviet troops also attacked the Baltic states and Finland.

Following these events, part of the Trotskyist Socialist Workers Party in the United States, including part of the leadership, changed their positions on the character of the Soviet Union. They capitulated to a strong pressure of bourgeois democratic opinion in media and “left circles” to equate the Stalinist dictatorship in Soviet Union with that of Hitler in Germany.

Taking these steps, the opposition that developed in the SWP rapidly also abandoned Marxist theory and the need for a revolutionary party. In defence of Marxism should be studied carefully, not just glimpsed at, to understand the need to combine a strong theoretical ground with concrete analysis.

What was Stalinism?

Lenin and Trotsky were the leaders of the Russian Revolution in 1917, securing that the working class, with the support of the peasants, took power for the first time in history. They were also the first to recognize the weaknesses and dangers for the new state, especially when it became isolated following the defeat of revolutions in Germany and other countries.

A bureaucracy developed, with Stalin as its leader, with defending status quo and achieving “stability” as its first priority, gradually adding its own desire for privileges and power. Stalin, who had played no leading role in 1917, was incapable to give advice to the German revolution in 1923 and the Chinese in 1925-27, which both were defeated.

In the 1920s, the bureaucracy was an unconscious brake on revolutions, but later it became a conscious brake to stop workers revolutions and struggles, particularly in Spain in 1936-39.

In the Soviet Union, they conducted an actual civil war against all remnants of Bolshevism that led the workers to power in 1917. The Stalinist regime used purges, prison camps, show trials and executions against any opposition, particularly the real Marxists.

During the living process of Stalinism coming to power, Trotsky many times posed the question of “Thermidor”, referring to counter-revolution in France in 1794. At first, Trotsky believed Thermidor in Russia would mean the destruction of the workers’ state. In the early 1930s, however, he realised that view was a mistake. Thermidor was a political, not a social, counter-revolution. In France, Thermidor meant a counter-revolutionary regime change, but the new regime kept the new capitalist-bourgeois economic system that the revolution had established.

A capitalist economy can have different regimes – from fascism to bourgeois democracy. In Russia, Stalin’s rule was a political counter-revolution. Capitalism was not restored, the planned economy survived. But a bureaucratic dictatorship replaced workers’ rule in the course of a prolonged bloody battle. This was made possible by Russia’s backwardness and isolation, plus the aggressive imperialist environment.

Trotsky’s conclusion was that Russia had become a degenerated workers’ state. It had a planned economy based on state property, with capitalism abolished.

On this basis, the Fourth International, founded by Trotsky, stood for unconditional defence of the Soviet Union against imperialist wars, without giving any support to Stalin’s regime. The program of the FI and its parties was for a political revolution to establish workers’ rule in the planned economy, establish a socialist society that would follow and develop the democratic decisions of the revolution in 1917, all of which were abolished by Stalinism. In a letter to Max Shachtman, Trotsky pointed to “the fact that the ideas of the bureaucracy are now almost the opposite of the ideas of the October Revolution“.

Vacillation and debate

The minority opposition that emerged within the SWP changed their position, arguing the attack on Finland and the pact with Hitler had fundamentally altered the character of the Soviet Union.

Trotsky, who had been given asylum in Mexico and was not allowed to enter the US, began his writings in this debate by asking them how Marxists should describe the Soviet Union, if not a workers’ state.

Some of them answered that the bureaucracy was a new class, others said the Soviet Union had become state capitalist. Others again argued that fascism in Europe, New Deal in the US and Stalinism were part of the same process towards bureaucratic state dictatorships. In that, they did not differentiate between revolution and counter-revolution. Fascism, as a tool of finance capital, of course did not expropriate capitalists.

Trotsky showed that the Stalinist bureaucracy was a temporary phenomena lacking a historic mission, while a new ruling class would be indispensable. The strong economic growth in the Soviet Union was not because of the bureaucracy, but a result of the planned economy and import of new technique. The bureaucracy was a brake on the development of the planned economy.

Stalinism was a totalitarian dictatorship, but not a stable regime. 50 years in advance – the process was delayed because of the outcome of the war – Trotsky predicted the negative consequences of the collapse of Stalinism and restoration of capitalism: weakening the world proletariat and strengthening of imperialism.

On this basis, Trotsky stood for the defence of the Soviet Union, despite the politics of Moscow which “completely retains its reactionary character” and were a “chief obstacle to world revolution” (he made comparisons to the fact that socialists still support trade unions who support their governments, seeing them as reactionary but necessary to defend against the class enemy).

The opposition in the SWP proposed instead that the party adopt the position “revolution against both Hitler and Stalin”, since their respective armies had divided Poland.

In replying, Trotsky showed the real situation in Poland. In the West, revolutionaries, jews and democrats were fleeing from the German army. In the East, it was landlords and capitalists trying to escape. Trotsky predicted that the invasion of the Red Army would be followed by expropriation of land and factories. This was confirmed by capitalist media, and even Menshevik newspapers in exile reporting of a “revolutionary wave” in Eastern Poland.

Trotsky warned that Hitler would turn his guns against the Soviet Union, to establish a fascist regime and restore capitalist property. When Hitler attacks, the most urgent task would be to defeat his troops.

What should Marxists say about the Red Army’s advance? The “primary concern for us”, Trotsky wrote, is not the change in property relations although progressive, but the consciousness of the world proletariat. The Fourth International was against seizure of new territories, against “missionaries with bayonets”. A revolution must have a firm basis in the working class and the poor to be successful. Where the invasion has already taken place, Trotsky argued for independent working class expropriation of capitalists and landlords.

How Trotsky approached the debate

In this debate, Trotsky combined sharp political polemics with always stressing the need for unity. He underlined how SWP members and leaders up till then had agreed on the crucial issues of the character of the Soviet Union.

The debate was necessary, but it would be “monstrous nonsense to split with comrades”, Trotsky wrote, “it would be prejudical if not fatal to connect the ideological fight with the perspective of a split, of a purge, of expulsion”.

He was in favour of “censure or severe warning if someone from the majority” made such threats. If not, “the authority of the leadership would be compromised”.

Trotsky proposed how the debate should be conducted. Both sides refuse to make any threats against their opponents, and if there were any, there should be an investigation by the National Committee or a special commission. There should be loyal collaboration from both sides. James P Cannon, who was close to Trotsky, agreed and put that position in the party leadership.

Trotsky of course had long experience of debates, from Russian Social Democracy and the Bolsheviks: “Even if there have been two irreconcilable positions, it would signify not a ‘disaster’ but a necessity to fight out the political struggle to an end.”

Advising Max Shachtman, a leading member who changed his position, Trotsky proposed fresh studies, to raise the issue in leadership but not immediately strive for a new fixed position.

A petty-bourgeois opposition

Trotsky and the majority of the SWP characterised the new minority grouping as a petty-bourgeois opposition. What does it mean?

Instead of developing their positions and analysis, the opposition was spreading “episodes and anecdotes which can be counted by the hundred and the thousand in every party”, attempting to find mistakes and faults. Inside the party, they had “almost the character of a family” or a clique.

Trotsky underlined some traits of this minority. They had disrespect for traditions of their own organisation and a disdainful attitude towards theory. This was particularly the case with James Burnham, a philosophy professor (34 years old) who had joined the party in 1935 and been given the post as editor of the party’s theoretical magazine New International.

Burnham was opposed to dialectical materialism, the philosophy of Marxism, comparing it to a religion. This position was neglected by other leaders of the minority. Already before the debate, in January 1939, Trotsky had criticised Schachtman for an article he wrote together with Burnham in New International, declaring “one of us for dialectics, one against”. The content of the article was good criticism of ex-Marxists who had already turned against socialism because they could not stand the pressure in society, such as Max Eastman.

Trotsky warned that not debating out dialectics with Burnham was a big mistake. The defence of dialectical materialism in this book explains the philosophy better than in most other Marxist works. Dialectics explains that everything in society and nature continuously change, in processes that develop through contradictions, with changes from quantity to quality and sudden leaps. Politically, dialectics are general laws for development of society and the class struggle, Trotsky summarised.

Instead, the opposition, under the strong influence of Burnham, used fixed abstractions. They had concluded that the Soviet Union was no longer a worker’s state, but could not answer what had changed in quantity or quality. Where from to where – what processes were there? The opposition lacked both theory and concrete analysis.

Burnham also stressed his “personal independence”, not being prepared to become a party fulltimer, in a situation when the full-timers were absolutely necessary in building the party. That also pointed to a lack of understanding of revolutionary centralism.

Other traits of the petty bourgeois opposition were political nervousness, and a habit of jumping from one position to another, including a light minded choice of allies in the faction fight.

Unity and factions

As an overall description of how the debate developed, Trotsky wrote: “The opposition opened up a severe factional fight which is now paralysing the party at a very critical moment. That such a fight could be justified and not pitilessly condemned, very serious and deep foundations would be necessary. For Marxists such foundations can only have a class character.”

It was clear that the minority started a vicious faction fight without a serious political basis. The majority stood firm behind the program and perspectives of the Fourth International. It was a working class position, compared to the opposition’s increasingly distancing themselves from revolutionary socialism, a petty-bourgeois trait. Trotsky did not discover this petty-bourgeois tendency for the first time in 1939, but gave many examples where he had raised warnings in the previous years.

For example, when Shachtman three years earlier believed that the Socialist Party in the US (a broader party the Trotskyists worked in and were expelled from in 1937) was developing into a revolutionary party.

Despite this analysis, Trotsky advocated unity. This in contrast to Martin Abern, an opposition leader, who used the threat of split to frighten members. Other opposition leaders wanted to go public with the debate.

Only weeks before the minority split, in April 1940, Trotsky stressed the necessity of internal democratic rights. “But if the unity is preserved, you can’t have a Secretariat composed only of Majority representatives. You should possibly have a Secretariat even of five members — three Majorityites and two Minorityites.”

When Trotsky pointed to the inner contradictions of the minority faction, Shachtman replied by giving historical examples of “blocs” involving Trotsky and the Bolsheviks. Trotsky replied by showing how, for example, the bloc with Kamenev and Zinoviev against Stalinism in 1926 was correct. But such a bloc did not hide the political differences between its members behind common programs. And it was clear that Trotsky’s supporters were the strongest force in the bloc.

In the US in 1939-40, Shachtman formed a faction, but in fact it was a bloc of differering forces, directed at the working class majority of the SWP. And within the faction, the dominant forces were Burnham and Abern. Shachtman was only their short term political alibi for leaving Marxism.

Even at this stage, Trotsky took a patient attitude, writing that events can change individuals, who can then re-establish themselves in the revolutionary party. He even gives himself as an example. Trotsky did not join the Bolsheviks until 1917, where he immediately played a decisive role.

Five years earlier, in 1912, he attempted to unite all different tendencies of the Russian Social Democracy: “I had not freed myself at that period especially in the organizational sphere from the traits of a petty-bourgeois revolutionist. I was sick with the disease of conciliationism toward Menshevism…”

Political clarity

Politically, the debate expanded to more issues. Trotsky of course understood that not every article or text needed to draw all conclusions, but stressed the need for members writing such material to understand the full program and analysis.

The minority moved in the other direction. They wanted to reduce the party’s program to “concrete issues”, which led Trotsky to make comparisons to debates in Russia, against the economists and the narodniks, who both avoided broader political issues. In 1939-40, the SWP minority thought the war was concrete, but the worker’s state wasn’t.

Shachtman quoted Lenin who in a debate with Trotsky in 1920 said, “workers state is an abstraction”, and that Russia was not a workers’ state, but workers and peasants state. However, Shachtman had missed that Lenin some weeks later concluded that he had been wrong, Russia was a “workers state with peculiar features” , those features being a peasant majority population and bureaucratic defects.

Shachtman used the expression “a degree” of degeneration in Russia, yet he was in alliance with Burnham who, despite not believing in dialectics, had concluded there was a qualitative change of the Soviet Union, equating it with Nazi Germany. The minority was not united, and soon after the minority split and formed the new “Workers Party”, Burnham left and developed into a leading reactionary.

There are many other concrete events analysed in this book: the events in Finland in the beginning of the war, how Marxists should act in the Spanish civil war, Marx’s position on bourgeois wars.

Trotsky’s general advice to members of the Fourth International was to orientate to and assist the working class, to strikes and trade unions, at the same time warning that there are always “opportunist deviations” in the unions.

80 years ago, Trotsky showed how the crisis in revolutionary leadership that broke out with the Social Democratic capitulation for World War in 1914 had not yet been solved. Some socialists blamed the proletariat for this, as some socialists did in Russia following the defeat of the revolution in 1905.

The reply to that came in 1917, when the Bolsheviks were able to create such leadership. Marxists today are struggling with a much different objective situation than 80 years ago. On one hand, the working class has grown a lot in size and thereby sets limits on reaction, on the other the labour movement in most places has to be rebuilt. This has led to explosive movements from below in many countries.

The need to build revolutionary marxist parties and an international are as urgent as in Trotsky’s time, if not more, with the deepening climate, economic, social and political crisis. To study and use In Defence of Marxism’s lessons on the need for a solid theoretical basis, concrete analyses, correct methods in party building and debates will be crucial in the stormy period ahead.