This article is republished from the archives of ISA.

Recent events in Iran have demonstrated once again the revolutionary energy of the Iranian masses, and particularly the working class. Articles written at the time by members of the CWI, since renamed as ISA, analyse the events of the revolution, and how Iran then ended up as a reactionary theocratic dictatorship.

After over a year of protests, strikes and confrontations with the hated security services, the hated Shah of Iran, Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, and his family were forced to flee the country in January 1979. The first article written by Lynn Walsh was first published in the Militant newspaper 26 January 1979.

Iran — The Rise and Fall of the Pahlavi Dynasty

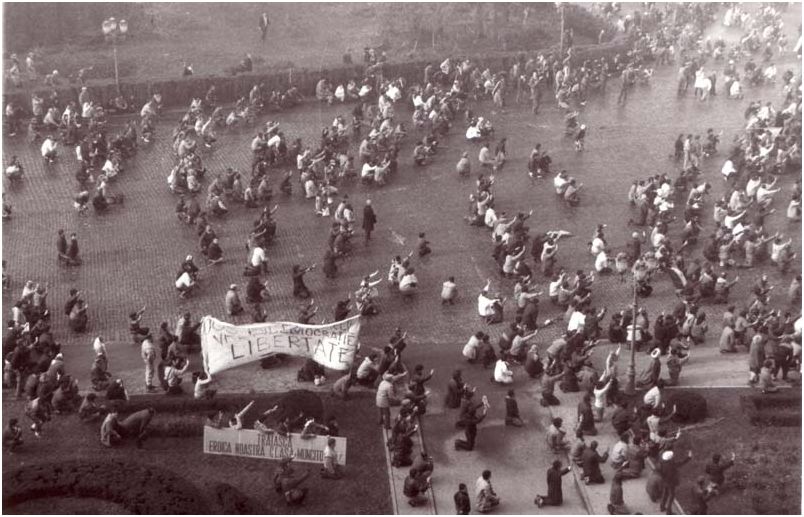

When the Shah finally left the country last week, hundreds of thousands of jubilant demonstrators filled the streets to celebrate his departure. Portraits and statues — those which remained — were torn down and destroyed. The remnants of the Peacock Throne crumbled like a mummy exposed to the air.

There was no mistaking the profound hatred of the Iranian masses for the Shah and his monarchical dictatorship, which was soaked in the sweat and blood of the Iranian masses. Despite the Shah’s grandiose claim to be the true son of Iran’s 2,500 year-old monarchy, his Pahlavi ‘dynasty’ dates only from 1925. It was founded by his father, Reza Khan, who far from being born to rule actually seized power through a coup in 1921.

Using the notorious Cossack Brigade, Reza Khan had drowned in blood the Gilan Soviet Republic set up in the north of the country under the impact of the Russian revolution. Although Reza Khan employed a few anti-imperialist phrases and carried out some limited reforms, his highly repressive state was dedicated to the defence of Iran’s property-owning exploiters.

Like many an upstart before him, Reza Khan set out to legitimise his regime by surrounding it with all the monumental pomp and ceremony of an ancient dynasty. He began the process of regaling Iran’s largely peasant population with cooked-up history and monarchist cant which was to reach unparalleled heights under his son. Reza Khan adopted a nationalist pose, but under his rule the country remained a satellite of British imperialism, and it was British business interests which sucked the main profits out of Iran’s developing oil industry.

In 1941, however, unsure of Reza Khan’s reliability in the war with Nazi Germany, Britain and Russia (allies for the moment) kicked out the first Pahlavi. Determined to have complete control over this strategically vital region, the Allies installed his more malleable son, Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, as Shah.

Puppet

The now departed Shah was from the very beginning a puppet, though in the last few years he had begun to tug ungratefully on the strings once held so tightly by his powerful mentors.

The Shah’s recent ignominious exit, moreover, was not his first. In the summer of 1953, the proud peacock of later years was forced to flee to Baghdad and thence to Rome by a mass movement on the streets.

The threat to the Pahlavi regime came from the radical nationalist movement led by Mosadeq. Iran’s Communist Party, the Tudeh, which was hamstrung by its enforced role as a tool of Moscow’s foreign policy and its lack of independent class policies, completely failed to gain a significant influence. As in India under Ghandi and in Egypt under Nasser, it was the liberal-capitalist nationalist party which came to the forefront of the popular movement.

In 1951 Mosadeq was elected prime minister, and promptly set out to nationalise the country’s oil to halt the drain of profits abroad. British imperialism immediately organised to bring him down, using both economic pressure and under-cover disruption in Iran.

In 1952 the Shah tried to dismiss Mosadeq but failed. The next year, however, the United States government, regarding Iran as a crucial “front line” buffer against Russian encroachment on the Middle East and South Asia, decided to act.

Mass demonstrations against the monarchy sent the Shah scurrying into exile. But Mosadeq’s National Front was just a loose grouping of middle-class politicians. It was incapable of fighting for social and economic demands which would have welded together a mass movement for a fundamental change in society.

CIA help

Exploiting Mosadeq’s shaky position, the United States — through the Central Intelligence Agency and with some help from British intelligence — set to work. Post-Watergate Congressional enquiries, as well as the first-hand testimony of ex-CIA agents themselves, have amply confirmed the CIA’s key role in the restoration of the Shah.

Gold and provocateurs were sent in to create turmoil and assist the reactionary forces. Bolstered with US arms and assured of American government backing, the Iranian army arrested Mosadeq and rolled out the carpet for the Shah’s return. Back on the throne, the Shah set about making his rule more secure — this time with the generous help of the US which wanted to build up Iran as a bastion of its influence.

All organised political opposition was crushed, and genuine trade unions were made illegal. With US support, the Shah began to re-arm his vast military machine, as much against mass opposition from within as any enemies outside. In 1956, moreover, the Shah re-organised the security forces, forming the now notorious secret police organisation, SAVAK, which ruthlessly hunted down his opponents.

Even so, the Shah was not completely secure. Despite the proclamation in 1963 of the so-called “White Revolution,” a program of reforms which would allegedly bring prosperity and democracy to Iran, that year saw another revolt against the dictatorship. By gunning down thousands in the streets, the Shah survived. Repression was again intensified. It was then, that the Ayatollah Khomeini was bundled off to exile in Turkey and later Paris — to await his moment of revenge.

The Shah then speeded up his reforms. The most important were in the countryside. Lingering feudal relationships were abolished — in order to hasten up the development of capitalist rent and farming techniques. This accelerated the massive exodus to the towns — a pre-requisite of the country’s modernisation.

Apart from the destruction of the traditional peasantry, industrialisation was achieved at an enormous cost to the rapidly expanded urban working class, which was forced to live and work under atrocious conditions. Modernisation, however, extended the Shah’s lease. Dragging Iran’s feeble capitalist class into the 20th century, the bonapartist monarchy largely pre-empted the economic program of the National Front, thus cutting away much of its support.

At the same time, like other self-appointed caretakers, the Shah and his family and their hangers-on grew fabulously rich on the commercial privileges they reserved for themselves — and on the proverbial “commission”, the opulent bribery. But like all “strong” states, the Shah’s was a regime of crisis. Lacking secure support even among the middle strata, it above all feared revolt by those carrying the main burden of economic development, the working class.

Hence the indispensability of SAVAK. In the last decade or so, this infamous organisation, with teams of sadists who deliberately set out to terrorise potential opponents by the virtually indiscriminate use of torture, became notorious throughout the world.

Bad dreams

After the fashion of most personal dictators, the Shah claims he knew nothing of the torture chambers: it was the unauthorised work of lackeys; he was misinformed by his advisers, etc. But who will believe these pathetic, despicable disavowals of a fallen dictator?

In the last few years, the sorcerer’s apprentice began to assert his independence in the grand style. Once the pawn of the foreign oil companies, Iran became one of the most militant members of OPEC after the 1973 Middle East war. Growing fat on the inflated oil revenues, the Shah bought even more industrial equipment from the West and augmented his armoury with the most expensive and sophisticated weapons. Posing as the leader of a great power, Shah Pahlavi began to lecture the Western leaders on the dreadful decadence of their societies, and pompously advise them on the best way to deal with political opposition and strikes.

But the Shah’s sleep, it seems, was disturbed by bad dreams. He suffered from a recurring nightmare in which he saw the resurrection of toil and trouble. He and his family, reputedly one of the richest in the world, prudently deposited their cash in Swiss banks and bought up property in Europe and America — as a hedge against revolution.

In fostering industrial development to aggrandise his regime, however, the Shah prepared the means of his own destruction. Opposition can be repressed for so long. But the development of factories, transport, oil production, cannot but produce a working class which, as it grows and begins to feel its strength, will demand a share of the new wealth — and push against the bars of the dictatorship.

The revolutionary events of recent weeks, which have once again sent the Shah scurrying into exile, more than likely for ever this time, signifying the coming-of-age of Iran’s youthful proletariat. Having brought down the Shah they will now dig a grave for all the other exploiters on their backs.

Having overthrown the Shah, a choice faced the Iranian working class, either organize its own revolutionary alternative, or allow other anti-working class forces to seize the initiative. Due to the betrayal of the left leaders, Ayatollah Khomeini, who returned from exile in February 1979 was able to do this. In an article published in Militant International Review in July 1979, Bob Labi reviewed the then current stage of the revolution.

Iran: New Stage in the Revolution

The rapid development of the Iranian revolution since the February 10-11 insurrection has demonstrated clearly that the Iranian masses saw the Shah’s overthrow as a green light for deepening their struggle for a better life. The past few months have shown how the tremendous pressure of the workers and peasants has forced the new regime, headed by Ayatollah Khomeini’s unelected Central Revolutionary Council, to sanction the most radical measures.

Barely four months after the Shah’s rule collapsed Iran’s banks, insurance companies, and the major part of its industry were nationalised without the owners being able to offer any open resistance. These nationalisations marked a new stage in the Iranian revolution. The takeovers were a major blow against capitalism and imperialism which will have an impact throughout the Middle East and Asia. Imperialism’s inability to organise any open opposition, for the present, exposed its weakness in the face of the Iranian working masses’ immense pressure for a fundamental change in society.

The February insurrection opened the floodgates to a deluge of struggles. But Khomeini and Bazargan, the Prime Minister of the Provisional Government, immediately attempted to restrain the masses. After striving to avoid an uprising Khomeini frantically tried to limit the scope of the Tehran fighting, so as to preserve at least part of the old army. Alarmed by the arming of the masses the next day Khomeini demanded the immediate return of all the captured weapons to the barracks or mosques.

When following the insurrection, a wave of industrial struggles began, Khomeini urged workers to ignore militants with “attractive slogans” and denounced those workers who wished to continue the general strike until all their demands had been met as “traitors. We should smash them in the mouth.” Bazargan began at once complaining about the masses’ “ludicrously high expectations of material gain as a result of the revolution.”

But all these pleas and threats were to no avail. Workers maintained their struggles to secure a better deal. Strikes and factory occupations developed. In many workplaces workers elected committees which challenged the bosses’ authority to run the plants. In those factories where the bosses had fled the workers attempted to re-start production themselves and demanded that the Government take their plants over. Mass demonstrations of the unemployed took place and there were mounting clashes with Khomeini’s Revolutionary Islamic Guards as they attempted to restrict the workers’ movement.

Bosses flee

The driving force behind this upsurge is the grave crisis gripping Iran and the workers’ new-found consciousness of their own strength.

In the insurrection’s aftermath over a quarter of the working population, 3 to 3.5 million, were estimated to be unemployed. Many factories had shut down due to lack of supplies or because their owners and managers had fled. Most of the bosses got out either before the insurrection or as soon as Iranians were allowed to leave the country. The mass exodus of the Iranian capitalists was similar to the Eastern European bosses, abandoning their property, before the advancing Red Army in 1944/45. Only a pale shadow of the Iranian bourgeois remains in Iran at present.

Many of the bosses were not prepared to consider re-starting production or new investment, let alone even returning to Iran, until the country was once again under the control of a stable capitalist government. This is what Bazargan tried to create, but the movement of the masses, and their impact on Khomeini, has blocked this so far.

Economic crisis

Khomeini and his unelected Central Islamic Revolutionary Council have attempted to maintain their position and power by balancing between the different classes. Khomeini and the circle around him had no clear idea of where they were going. They held various utopian ideas like abolishing interest charges and holding down prices by pleading with the shopkeepers. But Khomeini’s religious dogmas alone are not capable of satisfying the masses’ demands. The scheme to abolish interest charges is likely to be dropped, though they will be called “service charges” to give the appearance of change! Despite Khomeini’s pleas inflation is estimated to be running at 10% per month!

The extreme weakness, at present, of the capitalist class and the fragile condition of what remains of the capitalist state machine at the same time as there is a mighty revolutionary upsurge unfolding has led to Khomeini being pushed into granting the masses enormous concessions. These concessions, often made under pressure on the spur of the moment, include free medicine and transport, cancellation of power and water bills and the putting aside of £500 million in the budget to subsidise essential consumer goods.

The nationalisation decrees were by no means planned in advance. Indeed in the first days after the final collapse of the Bakhtiar government and the Shah’s regime various spokesmen of the new “revolutionary” government gave no hint of any planned nationalisations. The new Central Bank governor Mohammad Ali Mowlavi stated that there would be no bank nationalisations and that “free competition would be encouraged as a means of strengthening the private sector.” But unfortunately for Mowlavi and the capitalists the Iranian workers did not see things their way.

The Iranian capitalists’ flight left a vacuum which the working class immediately began to fill by assuming the responsibilities of management themselves and demanding that the Government take the companies over.

The drastic economic situation forced Khomeini to declare in mid-March that Iran’s “economic system is bankrupt.” With workers securing their wages despite their factories not operating, prices rising by 10% a month, mass bekaran (jobless) marches and the development of peasant land seizures Khomeini was being pushed into both sanctioning and taking radical action to satisfy workers demands or else risk the undermining of his support. Against this background Khomeini was forced to ratify the workers’ moves to take over large sections of industry with the nationalisation decrees at the beginning of July.

The tremendous workers’ movement which has wrung these concessions from Khomeini has developed from below. Not one of the main ‘left’ organisations were prepared or able to give a socialist lead. The Tudeh (“Communist”) party trailed behind Khomeini, urging him to join with them in a “United Popular Front.” The ’Marxist’ guerrilla group, the Fedayeen-e-Khalq, while putting forward general ‘leftist’ slogans did not advance any rounded out socialist program and petitioned Bazargan for a place in his capitalist government! The Islamic based Mojaheddin guerrilla leader Massoud Rajavi went further when he said that “ownership by industrialists faithful to the nation was in no danger.” In reality, the policies of all these groups have trailed behind the masses demands, which have forced Khomeini to go further than any of these tendencies called for after the old regime’s collapse.

Despite the absence of any clear ideas of where they are going Khomeini and the mullahs around him have risen to power in this, the first stage of the revolution. This was fundamentally because, in the absence of any alternative revolutionary leadership, the mosques became the fulcrum for the working masses’ battle against the Shah.

Khomeini’s basis

The Iranian workers spearheaded the struggle against the Shah through the mass demonstrations, the four month long general strike and the February 10-11 Tehran insurrection. But despite this leading role, as yet no independent working-class leadership has come to the fore, rather it has been Khomeini’s supporters (now organised in the Islamic Republican Party) who have appeared as the dominant force in the revolution. This is rooted in the enormous growth of Khomeini’s influence in the last year which resulted from a number of factors.

Firstly, Khomeini’s clear position against the Shah provided a pole of attraction to the masses, especially in comparisons to the repeated offers of compromise the liberal National Front leaders made to the Shah.

As Khomeini’s support developed, helped along by the sizeable publicity he was getting, all the other major opposition forces began to tail-end him, thereby further increasing his standing. The Tudeh repeatedly made declarations of support for Khomeini, deliberately ignoring his reactionary and anti-communist statements. The Tudeh’s Central Committee statement of January 17, 1979, for example, stated its “full support for the formation of the Islamic Revolutionary Council initiated by Ayatollah Khomeini … The Party, having found the political program of Ayatollah Khomeini (particularly the position adopted by the Ayatollah in the past few weeks in his speeches and interviews) in accordance with the position adopted by the Tudeh … declares itself ready to support the following statements made by the Ayatollah.” This was followed by an extremely selective list of quotations from the Ayatollah, which omitted any hint of reactionary policies.

In this situation where there was no other alternative program or leadership being put forward, it was inevitable that Khomeini would come to head the anti-Shah movement.

More fundamentally, however, Khomeini’s strength reflects the role and influence of religion in a backward society like Iran, where over 65% of the population are illiterate and over half still live in the countryside. The Iranian working class is a very young working class, both in terms of its age and history. In many factories the unskilled workers’ average age is 20, which is one of the reasons for the enormous energy and resilience which it has demonstrated in the last year.

Bazargan’s weakness

The crushing of the trade unions after the Shah’s August 1953 coup against the liberal Mossadeq government and the massive recent expansion of industry have meant that most Iranian workers are first generation workers without a tradition of organisation, having moved directly from the countryside into industrial work. While the working class made giant strides forward in its understanding and organisation as the revolution has unfolded there has not yet been the development of an independent working-class movement.

During the Shah’s dictatorship the Mosques, as a result of the Shah’s clashes with the mullahs in the 1960s, tended to become centres of opposition to the regime. They provided a relatively safe venue where the masses’ grievances could be aired and opposition developed. This further reinforced the mosques and mullahs’ position in the developing mass movement.

Khomeini’s call for an “Islamic Republic” undoubtedly caught the imagination of the working masses. The “Islamic Republic” was interpreted by workers: as a republic of the “people,” not the rich, where their demands would be met. There was no mass support for Khomeini’s ideas of turning the clock back to the Middle Ages. Indeed, Khomeini’s reactionary whims and policies, along with the continuing inflation and unemployment, are already beginning to undermine his support.

Since the insurrection Bazargan, the Prime Minister appointed by Khomeini, has attempted to stabilise the situation in the capitalists’ interests, but has so far failed in this task. The Bazargan government has attempted to rebuild the state machine crippled by the mass uprising, but while certain progress has been made in this area, Bazargan has been incapable of creating any real alternative to Khomeini’s forces.

The Provisional Government’s attempt to organise a capitalist democracy was in reality an effort to restrain Khomeini and so gain time to recreate the capitalist state machine. But the rapid pace of developments undermined these plans for the moment. The Government has no forces with which to confront Khomeini and this weakness has forced Bazargan to co-operate with Khomeini, both to co-operate in restraining the left and in the hope of preventing the Ayatollah from stumbling into carrying out even more anti-capitalist measures.

But while the masses’ tremendous pressure and the capitalists’ flight has forced Khomeini both to ratify and himself take anti-capitalist measures, this has been balanced by attacks on the developing left and workers’ movement. Khomeini has continuously attempted to restrain the working class and delay the development of political parties.

Constituent Assembly

At first last year Khomeini called for a republic and the restoration of the 1906 constitution, which gave the mullahs constitutional power to supervise the Majlis, the elected assembly. Under the pressure of the mass movement Khomeini was forced to then call for an elected Constituent Assembly to draw up a new constitution. But as soon as the old regime collapsed the Ayatollah sought to abandon any idea of a Constituent Assembly. Khomeini’s group correctly feared that the holding of elections would accelerate a political polarisation and the growth of rival political parties, thereby awakening their support. Only under pressure did Khomeini agree to the election instead of a 73-man Council of Examiners, with limited powers to check the new draft constitution.

During the election campaign for the Council of Examiners Khomeini’s unelected “Immam komitehs” continued attempting to hinder the development of any independent working class activity and oppositional political parties. Harassment, arrests, press censorship and shootings have all been used against workers’ organisations and activities.

On the same day that the insurance companies were nationalised Khomeini’s Central Council published a Bill setting up special courts with the power to impose two to ten year jail terms for “disruptive tactics in factories or worker agitation.” The Ayatollah’s draft constitution, finally published in June after four months secret wrangling, provides for a strong President with wide powers and a Supervisory Council – made up of priests, professors and judges – to check that all laws passed are in accord with Islam. Khomeini’s constitution is designed to limit the Majlis’s powers and give the clergy effective control of the country.

A glimpse of what this could mean has been shown as Khomeini has given vent to his obscurantist feudal prejudices. The banning of music and mixed swimming, the whipping of unmarried lovers and the shooting of prostitutes as “a lesson for innocent girls who must stay with their families” are just a few examples of how Khomeini would like to order society. Khomeini is relying on the enormous following which he still has, reinforced by the anti-capitalist measures he has taken, to allow him to implement his reactionary social policies and turn the clock back to the Middle Ages. But already these ideas are encountering opposition.

Reactionary measures

Khomeini’s retreat in March over the wearing of the veil was forced by workers being opposed to the attempt to victimise and attack unveiled women. Compulsion smacked too much of the old regime which the workers had battled over for over a year to remove. Gradually the enforcement of Khomeini’s reactionary whims is alienating more and more Iranians. Additionally, the continuation of mass unemployment, roaring inflation, high rents and unsolved social problems, despite the overthrow of the Shah’s regime, is radicalising the working class. Consequently, Khomeini’s position, while appearing strong at present, is by no means permanently secure.

A further source of opposition to Khomeini’s regime has been the national minorities. In Iran only just over half the population are Farsi (Persian) speakers, most of the rest being national minorities. The removal of the Shah’s dictatorship provided a signal to these minorities to attempt to end the repressive measures which the Shah imposed, such as the suppression of their languages and seizure of their lands, and to win autonomous rights. The proposed constitution, however, does not grant the minorities autonomy, let alone the right of self-determination. Both Khomeini and Bazargan, pursuing a Persian nationalist policy, have resisted the minorities’ demands and relied on the Farsi speaking population in the minority areas to retain their power.

These policies have resulted in the armed clashes in many areas as Bazargan and Khomeini have used the army and the Revolutionary Islamic Guards to maintain control, particularly in the oil-rich Arab areas in southern Iran.

Iran is in a contradictory situation. While the capitalists have fled and the nationalisations have made massive inroads into capitalism’s power, unless this process is taken to its conclusion — with the drawing up of a plan of production and a state monopoly of foreign trade — there will be the possibility of a capitalist restoration.

Khomeini’s position reflects the contradictions opening up. On the one side the Ayatollah denounces the left and attempts to enforce vicious reactionary laws. But at the same time Khomeini’s Council has been compelled by the pressure of the situation to ratify the takeovers. Khomeini has been pushed along by events, being forced, for example, to retrospectively approve the executions carried out by the local ‘Immam komitehs’, which themselves have been under pressure.

A vacuum exists in Iran. Either there will be a consolidation of the nationalisations, leading to the overthrow of landlordism and capitalism, or there will be a victory for reaction.

Reaction in Iran would be unlikely to be based upon the Shah’s old ruling elite, most of whom have now been liquidated by the firing squads, rather it would coalesce around a new pole of attraction. Already in the recent months steady progress has been made by the officers in rebuilding the army. The reactionary policies of those officers who remain was demonstrated by the now retired military police chief General Rahimi who demanded that armed force should have been used sooner against the minorities and was “concerned that the army was being forced to hold back when there was unrest in the country.” It would only be a matter of time before the officers attempted to use the troops against workers, as well as the national minorities. But at the same time the army is by no means immune from the turmoil in society. In the first few months since the insurrection there have been three Chiefs of Staff, their short spells in office reflecting the unrest in the military’s ranks.

Despite the anti-capitalist measures which he has been forced to sanction Khomeini could become the head of a future counter-revolutionary movement. The Ayatollah has already revealed his fundamentally reactionary views. In the course of mounting conflicts with the working class and nationalities Khomeini’s committees and militia could develop into the spearhead of the counter-revolution.

But under the pressure of events Khomeini could be forced to move in the opposite direction and complete the expropriation of capitalism, as did the Dergue in Ethiopia. This would be an immense step forward in Iran. A planned, nationalised economy would lead to an enormous development of the economy, a raising of living standards and a strengthening of the working class’s size and potential power. But such a movement under Khomeini’s clergy, while breaking Iran free from the chaos of capitalism, would not create a workers’ democracy.

The fact that it is conceivable that a feudal religious obscurantist like Khomeini could preside over the overthrow of capitalism in Iran is a reflection of the depth of the crisis and the world balance of forces.

Capitalism cannot develop Iran. The oil-based boom of the mid-1970s while producing, for a short time, dramatic growth rates — not only failed to resolve the old problems but created new evils, like the 40 shanty towns around Tehran’s centre. Indeed, in this period of world economic upheavals capitalism can only continue in Iran on the basis of grabbing back the gains the workers have won, even in 1976 the Shah tried to impose an austerity program.

However, the Shah’s overthrow demonstrated the workers’ power and it is this power which, at present, stands in the way of counter-revolution and is forcing Khomeini in an anti-capitalist direction. On a world scale imperialism cannot openly intervene in Iran at present.

Workers’ Party needed

The Iranian working class overthrew the Shah. In this struggle it became conscious of its power, but not conscious of how to organise the power it held in its hands after the February uprising. This resulted from the absence of a Marxist leadership and a mass party capable of drawing the necessary conclusions from the course of the revolution and the crisis gripping Iran. A Marxist party would have explained the necessity for the working class, in alliance with the national minorities and poor peasants, to take the power in its hands and carry through the tasks of the socialist revolution.

The absence of such a party allowed Khomeini and the mullahs to utilise their great popularity and the mosque’s organisation to step into the void created by the Shah’s fall and the workers’ failure to take hold of the state power. Nevertheless, it is still the Iranian workers’ power and demands which are determining the pace and direction of events in Iran today, despite being without a cohesive socialist leadership.

The breaking of capitalism and landlordism and the continuation of the mullah’s power would result in the creation of a regime in the image of Russia, Eastern Europe, China etc, with the difference that in place of the Stalinist ideology of those regimes Khomeini would impose the ideas of Islam. In such a regime, a deformed workers’ state, the rulers of society would be a religious-bureaucratic elite living off the back of a nationalised, planned economy. Though it would be likely that with a further development of industry the mullahs would tend to lose power to those sections of the bureaucracy based in the state machine armed forces and industry.

But while the establishment of a planned, nationalised economy even on these distorted lines would mark a huge step forward for Iran and be a terrific blow to world imperialism, the Iranian workers would then be faced with the task of overthrowing the new ruling elite in a further, political, revolution and establishing a workers’ democracy before there could be a movement towards socialism.

The Iranian revolution has demonstrated the working class’s enormous power and its instinctive desire to transform society. But at the same time the revolution’s rapid, even if distorted development shows how the depth of the crisis can propel the movement along even in the absence of a revolutionary party. But the grip of Khomeini’s reactionary influence and the still present threat of counter-revolution shows the urgent necessity for the creation of an independent, mass workers’ party, armed with a Marxist programme. Only on the basis of the Iranian workers consciously taking power and beginning the re-organisation and re-building of society will it be possible to prevent either the establishment of a new dictatorship in the future or of a deformed workers’ state requiring a second, political revolution.

Already however the Iranian revolution has overthrown the Shah, weakened imperialism and set an example towards the rest of the world of how no dictatorship can survive forever. The revolution is far from over. The Iranian workers will as a result of their own experiences increasingly see the need for a Marxist party. Only on this basis can capitalism and landlordism be overthrown and a Socialist Iran created, uniting on a free and equal basis all the peoples in Iran, and setting a revolutionary example to the workers and peasants of the world.

Ayatollah Khomeini died ten years after the revolution. To review the decade of his rule Jeremy Birch wrote the following article for Militant on 16 June 1989.

After Khomeini

They had to hold two funerals for Ayatollah Khomeini. The first was swamped by two million mourners, working themselves up into a frenzy of grief. The helicopter bringing the body to the burial ground was besieged. The shroud was torn from the body and ripped into shreds by zealots desperate for a fragment of the ‘holy’ fabric. At least eight died in the crush. And in a final macabre indignity, the body fell to the ground. A second, successful attempt to bury it was held that evening. This was the largest gathering in Iran since Khomeini made his triumphal return in 1979. His first address to the enthusiastic masses was from the very same cemetery where he has now been buried. But ten years ago, the thousands rallying at the Behest Zahra Martyrs cemetery were celebrating the high point of a revolution. The Shah had just fled the country. Under the impact of mass demonstrations and strikes the state apparatus, armed and financed by US imperialism, had cracked. Only the hated SAVAK secret police remained loyal to the monarchy. They had nowhere else to go.

Power resided in the streets of Tehran. Factory committees sprang up. But the abject failure of the left organisations, especially the Tudeh (Communist Party), to lead the independent movement of the workers allowed the mullahs (Islamic clergy) to dominate. An ageing cleric, Ayatollah Khomeini, became the spiritual and political leader.

Khomeini and the mullahs had an aura of opposition to the Shah. But their opposition was primarily to the Shah’s industrialisation and modernisation of Iran, which threatened their control of education for example. Religious lands were also taken over. The potential for socialist democracy existed but the Tudeh dissolved itself into Khomeini’s movement.

Many of the big capitalists followed the Shah into exile, others were irredeemably compromised by their association with him. Workers took over many of the factories and the mullahs were forced to bring them into state ownership. A state monopoly of foreign trade was established.

The mullahs’ antipathy to the “decadence” of the west was translated by the masses into opposition to foreign interference and exploitation. Khomeini utilised the occupation of the US embassy in Tehran of November 1979 to oust liberal capitalist politicians from the government and consolidate power.

The mullahs’ primary basis was among the bazaar capitalists — traders and smaller capitalists — who were opposed to the influence of foreign capital and the multinationals. Their assets were left untouched.

As the revolutionary energy ebbed the mullahs moved against the workers’ committees. They mobilised the urban poor, especially the many thousands who had flocked to the cities from the countryside but could not be absorbed by industry.

These became the mainstays of the Revolutionary Guards who dealt with strikers, worker activists and finally, despite their cheerleading for the mullahs, the left organisations.

A brutal theocratic regime was instituted, ruthlessly suppressing the rights of the working class. With scarcely any opposition tolerated, however, different pressures were reflected amongst the mullahs themselves. There were sharp clashes over the degree of state intervention in the economy and over trade and co-operation with the west.

Now, ten years after the revolution, Iran is facing enormous difficulties. The war with Iraq has left heavy costs — not just of 600,000 lives, but in terms of destruction of industry and of the vital oil terminals and serious dislocation of the economy.

Ayatollah Montazeri, Khomeini’s original named successor, fell from favour in March with his open admission of “shortcomings, discrimination, social injustice, low earnings of the deprived sector of society and soaring prices.” He challenged the prime minister: “You cannot any longer use the excuse of war for the long queues for basic foodstuffs and ration coupons.”

The faction around speaker of the parliament Rafsanjani recognises the necessity of western investment, loans and technology to rebuild Iran’s ravaged industry. President Khamenei, named as “leader of the revolution” in succession to Khomeini, also seems to back these ideas.

Earlier this year Khomeini himself agreed to foreign borrowing to finance major projects and loosened state control of foreign trade. The heavy industry minister Behzad Nabvai defended this: “If some people get rich this way we should not howl and say our socialist principles have been damaged. We should make the best use of all foreign exchange outside official channels.”

However, others within the regime, including Khomeini’s son Ahmad, are opposed to any economic relaxation or to links with the west. These differences came to a head over the death threat to Salman Rushdie.

The “radicals” convinced Khomeini to issue the threat but Rafsanjani and Khamenei were distinctly unhappy, recognising the damage it could do to relations with the west. But the hysteria whipped up among the Iranian masses in support of Khomeini’s call obliged Rafsanjani to issue still more blood-curdling demands, for the murder of five Americans or Britons for every Palestinian killed. He subsequently claimed he had been misinterpreted!

Now it seems that, with Khamenei, Rafsanjani has emerged as the dominant figure in Iran, not least because as acting commander-in-chief he has the allegiance of the army and of the Revolutionary Guards, which he has tried to bring under control by incorporating them into armed forces.

It was Rafsanjani who initiated a constitutional review which is recommending the presidency becomes an executive, no longer a largely ceremonial post. And the only candidate so far when Khamenei steps down as president is Rafsanjani, “We need a concentrated executive power,” he says. He stands for a more stable capitalist regime, less prey to the whims and squabbles of the mullahs.

Undoubtedly Rafsanjani and Khamenei will want to open up Iran to more foreign investment, allow more economic freedom to the capitalists, perhaps handing back state assets. But there will still be fierce opposition from others within the regime, even trying to organise protests in the streets through the fundamentalist network.

However, any idea that the “moderate” Rafsanjani offers anything better for the working class than Khomeini or the rigid fundamentalists should be scotched at once. He is reputed to have been a self-made millionaire before the revolution and now to hold a personal monopoly over lucrative pistachio nut exports.

He was instrumental in the bloody post-war purges in the armed forces. He is reported to have visited one barracks, ordered the arrest of 200 men and the immediate execution of 35.

However, it is the working class that will determine the final shape of Iran. Lacking leadership, the revolution was stolen from them. But despite the repression it is they the regime still fears.

The regime was alarmed by the growing anger at the privations of the war. It was Rafsanjani who convinced Khomeini of the need to seek an armistice, warning: “We could swing in the main square of Tehran.”

Now the regime is fearful of the impact of the 70 percent inflation and the four million unemployed. That is why they know they must try to restore the economy.

Khomeini’s death is an opportunity for the workers to think back over the dramatic events of the last decade and to learn the lessons. Only by relying on their own strength, their own organisations and their own independent program can they liberate the Iranian people from capitalism and religious obscurantism.