The killing of Lyra McKee on Thursday 19 April sent a wave of shock across Northern Ireland. Lyra was only 29 years old but had already made a name for herself as a journalist, an author and an activist. Whilst over 3,800 have died in the “Troubles” since 1969 some killings strike a particular chord. Lyra’s age means that she was a member of the generation which has only known the “peace” delivered by the Good Friday Agreement (GFA-also known as the Belfast Agreement), signed almost exactly 21 years before the day of her death. Her activism means that for many young people her life represents their hope for a better future. Amongst trade union activists, in particular, there is intense anger that Lyra was a journalist doing her job when she died.

Protests and vigils, initiated by the National Union of Journalists and local Trades Councils, and Lyra’s friends and family, took place in Derry, Belfast, Omagh, Enniskillen, Strabane, Cookstown, Newry, Dungannon, Dublin, Glasgow and London, and elsewhere, in the aftermath of her death. These were important events giving expression to the widespread anger and revulsion over her death.

Immense pressure was brought to bear on the group which claimed responsibility for her shooting, the New IRA. The political party it is linked to, Saoradh (“liberation”) responded to this pressure by calling off its Easter Monday parade in Derry, though it went ahead with a march through the centre of Dublin. One indication of the mood in Catholic areas is that other dissident republican groups openly criticised the New IRA and called on it to end its armed campaign. Within days, however, Saoradh had hardened its position, seemingly determined to ignore the views of its critics, and all the indications are that the New IRA intends to continue its intermittent attacks.

Paramilitaries can be pushed back

Most working people will have an understandable fatalism at this point-they are prepared to support protests but do not really believe that the dissident groups will listen. In fact, the lessons from the past are that determined mass action does work, even against groups with little public support, and which are determined to ride out periods of bad publicity.

One key example of when paramilitaries were forced onto the defensive is when the Official IRA shot dead Ranger William Best, who was in the British army and from the Creggan area of Derry city. He was killed while on home on a few days leave, in May 1972. The days after his death 200 women protested outside the Officials’ office and 1,500 marched in the area. Up to 5,000 working class people made their point by attending Best’s funeral. One week later, the Officials called a ceasefire, which marked the effective end of their armed campaign.

The Officials had a semi-mass base in 1972, had a left orientation, and were thus vulnerable to pressure from local working class communities. And the fact that the Troubles was then in its earliest phase meant that working class people had greater faith in their own ability to impact on events.

The situation is very different today. The half dozen paramilitary groups that continue in existence, in both communities, are much smaller than the Officials, and have little support. Their gangster methods and lack of politics means that they are treated with distain by most working class people. This does not mean however that they are immune to pressure from the working class. The Real IRA was also small and relatively isolated when it detonated the Omagh bomb in August 1998. It could not deflect the mass wave of protests across Ireland that resulted and was forced to call a ceasefire.

It did return to violence 18 months later when the immediate pressure had diminished but was severely restricted in its ability to mount an effective campaign. This does not prove that mass community pressure does not work but rather that it must be sustained. Crucially, an alternative way forward must also be demonstrated, in particular for young people in working class areas. If there is no other route to channel the anger and alienation of the youth in Catholic or Protestant areas, a minority will find their way into the ranks of the paramilitaries.

Deprivation, harassment and violence

Those who killed Lyra McKee are also members of the

generation who have grown up since the GFA. They were on the streets carrying

guns because the Agreement has not brought the promised “peace dividend”. They

instead live in poverty, and in many cases are exposed to regular harassment

from the PSNI.

Derry is the most deprived city in not just Northern Ireland but in the UK. The

Foyle constituency has an unemployment rate that is more than twice that of the

Northern Irish average (7% vs 3.5%). Almost half of Derry’s claimants (49%) are

classed as long-term unemployed, which is significantly higher than the average

for Northern Ireland (33%) and the UK (31%). The city also has the highest

proportion of people of working age who are “income deprived” (38%). For those

who are in work, their Gross Weekly median wage is only £324 per month, in

comparison with a Northern Ireland average of £393 (NISRA Annual Survey of

Hours and Wages 2017). Forty three per cent of the entire population of the

Derry-Strabane council district lives in some of Northern Ireland’s most

deprived wards.

The consultancy firm, PWC, publishes an annual ‘Good Growth for Cities’ report which ranks the UK’s cities according to “economic well-being”. Its 2017 report (covering the period 2014-16) placed ranked Derry bottom of 57 cities, and identified it as one of only two cities (along with Swansea) not to see any improvement in performance since the 2011-2013 study. Referring to Swansea and Derry, PWC concluded, “These cities have not seen reductions in unemployment on the same scale as their peers, and have seen worsening scores in areas such as health, work-life balance and income equality”.

Derry has one of the highest proportions of people under the age of 16 of any city in Europe. A 2017 report from the Western Health Trust showed that one in three of Derry’s children are being raised in poverty (the highest anywhere in NI) and it has the highest percentage of schoolchildren entitled to free school meals in Northern Ireland, at 43.3% (the NI average is 30.7%). It is little wonder that in a survey last year 95% of Derry’s young people said that they saw no future for themselves in the city, and could not envisage remaining there long term.

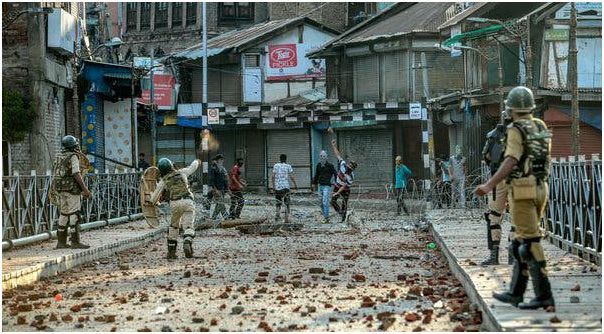

Alongside the grinding poverty which blights working class lives, the violence has continued, even if at a much lower rate than before 1998. There were 1,100 bombings and shootings, 787 paramilitary-style “punishment” attacks and nearly 4,000 reports of people forced to flee their homes in the ten years between 2006 and 2015. 160 people have died in the violence since 1998. The state is engaged in a campaign of harassment against those it suspects of dissident republican sympathies, especially young people. Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) officers have stopped and searched people 14,393 times in the Derry and Strabane policing areas since 2015. In the period from 1st October 2018 to 31st December 2018, a third of those stopped and searched were aged 18 to 25.

The role of the trade union movement

A way out of this misery must be charted. The trade union movement, which unites 250,000 Catholic and Protestant workers, is the only body which can now provide the lead which is required. A mass, trade union-lead campaign can check the growth of paramilitarism, get the armed groups off the backs of working class communities, and ensure that a new generation do not waste their lives in prison cells. But this will only be possible if the factors which propel young people into the ranks of the paramilitaries are addressed, and a political alternative is simultaneously created.

The trade union movement has a proud tradition of standing up against sectarian forces from all sides, especially when workers are under threat. Already this year paramilitary attacks have been answered by protests by working class people. In January, the public sector union, NIPSA, organised a rally in Derry after a series of attacks, disruption and threats. Vehicles were hijacked at gunpoint and there was a car bomb explosion outside the courthouse in Bishop Street. The New IRA was behind the bomb and the security alerts.

The NIPSA branch which organises staff in the courthouse took the initiative and was backed by the union, Derry Trades Union Council and the Irish Congress of Trade Unions (ICTU). As NIPSA President and Socialist Party member, Patrick Mulholland, explained at the time: “In the wake of Saturday’s bombing at the courthouse in Derry, and subsequent paramilitary and police activity in the city, public sector union NIPSA, which represents staff at the courthouse, has initiated a protest in opposition to paramilitarism, sectarianism and repression under the slogan ‘No going back’. “Those who carried out Saturday’s bombing in Derry aim to drag us back into futile conflict. Their actions achieve nothing but whipping up sectarian tension and potentially legitimising attacks on democratic rights. The bombing put the lives of ordinary people at risk, including NIPSA members”.

After Lyra’s death there was a similar ground-up, trade union-led, response. National Union of Journalist (NUJ) activists, including Socialist Party member and NUJ Executive member, Anton McCabe, took the lead in organising several protests. The Trades Councils in Derry, Enniskillen, Omagh and Mid-Ulster joined NUJ events or organised their own. NUJ activists came together in solidarity protests in Glasgow and London on the day of Lyra’s funeral.

What was missing though was a centralised response from the wider trade union movement. On multiple occasions in the past the Irish Congress of Trade Unions (ICTU) have called demonstrations across a dozen or more towns and cities after paramilitary attacks. Workers walked out for lunchtime rallies, and then did not return to work, resulting in, de-facto, half-day general strikes. The killing of Lyra McKee was an event which demanded such a response, but despite pressure from some unions, ICTU did not act. If instead of demonstrating only inertia, ICTU had issued a call for rallies and walkouts-a half-day general strike-in the immediate aftermath of Lyra’s murder, the widespread anger amongst working class people could have been mobilised into a powerful show of workers’ unity and opposition to sectarianism and the paramilitaries.

Even now the opportunity has not entirely passed. If ICTU were to make a bold call and organise a day of action within the next week, with Northern Ireland-wide mass protests, demanding that the New IRA and every other armed group should not just end their armed campaigns, but disband immediately, there would be a response across all workplaces and communities.

The lack of a clear lead means that the understandable anger of many has resulted in misplaced demands to effectively close Saoradh down as a political party. Closing its offices, banning its marches, and restricting its social media presence is not the answer. Such actions would give Saoradh the opportunity to adopt the role of the “victim”, and use it as a recruitment tool. The unions must oppose the repression which drives young people into the armed groups. This includes any restrictions on the activities of groups like Saoradh, not because we support the politics of Saoradh, or wish to facilitate their political campaigning, but because the history of the Troubles in Northern Ireland shows that repression does not work.

It is not only the absence of a robust trade-union wide response which is a problem, however, but the tendency of the unions to avoid politics. The only way to effectively challenge Saoradh and other organisations like them, on both sides of the sectarian divide, is by providing a political alternative. This means, however, challenging all the sectarian political parties, including those which lined up to condemn the New IRA in the last few days. The call by a priest at Lyra’s funeral for the DUP (Democratic Unionist Party) and Sinn Fein to “get together” is to sew illusions. Now talks between the parties are to be initiated by the British and Irish governments but this will solve nothing. These parties are part of the problem, not part of the solution.

A sustained trade union lead movement against paramilitarism, against sectarianism, against repression, and against austerity, must be launched now. On each and every occasion that working people face threats, intimidation and attack, the movement must respond, including through strike action, when necessary. And the trade unions must, with genuine anti-sectarian socialist groups and individuals, begin to build a mass political party that challenges sectarian politics and sectarian politicians. A united political voice for all working people, with a program to end poverty and to provide decent jobs, would over time, win wide layers away from the sectarian parties. Such a party would be capable of overcoming the sectarian division which blights the lives of working class people through a united struggle for a socialist future, and once and for all consigning the past to the past.