Erin Brightwell and Rob Darakjian are members of Socialist Alternative in the US.

A new women’s movement is emerging in response to the election of the misogynist Donald Trump, starting with the 2017 women’s marches and now with the #MeToo campaign. The potential power of the #MeToo moment has so frightened the political class, the CEOs, the 1% investors, etc., that dozens of famous abusers have been fired or forced to resign. This is a victory, but women have much more to win.

A real pathway for workers to deal with abusive bosses and coworkers, whether your boss is famous or not, can be won, but it will require a mass movement that takes the streets and disrupts the status quo. The last major women’s movement in the U.S. during the 1960s and 1970s was a period of sustained mobilization around women’s issues that won important reforms and changed the attitudes of millions on women’s roles in society. It also showed the limitations of liberal and radical feminism.

The women’s movement of the 1960s and 1970s emerged during an era of massive social upheavals nationally and internationally. In the U.S., the determined struggle of African Americans in the Civil Rights movement had a transformative effect on the consciousness of millions of workers and youth. The movement against the war in Vietnam was enormous in scale, drawing an estimated 36 million to protests during 1969 alone. The establishment was being challenged from all sides, and women, people of color, LGBTQ people, and workers were emboldened to take their fight against oppression and inequality to higher levels of organization and action.

The Birth of NOW

The National Organization of Women, NOW, founded in 1966, developed a strategy and tactics to deliver full legal equality of women to men. Although NOW often campaigned for demands that would benefit all women, NOW policies were centered around the concerns of educated, middle class women and were sometimes at odds with working class women’s interests.

NOW was effective in winning reforms through a barrage of lawsuits combined with protests and mass actions, particularly in employment discrimination. It began by pushing for an end to sex-segregated job listings in newspapers, combining lobbying efforts with picketing and demonstrations which succeeded in ending the practice by 1968. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, the federal agency tasked with enforcing the Civil Rights Act rules against discrimination in employment, only began enforcing the law on sex discrimination after a NOW campaign forced the change.

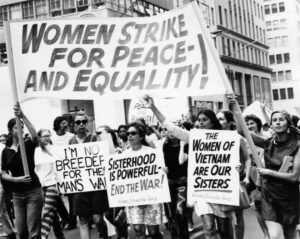

On August 26, 1970, the National Women’s Strike saw tens of thousands of women strike all across the country around three central demands; the right to abortion, the right to childcare, and equal opportunity in employment and education. Demonstrations varied in character from city to city, but it was because of the existence of NOW that the Women’s Strike was a nationally coordinated action.

In New York City, fifty thousand women marched down 5th Avenue, and a banner was hung from the Statue of Liberty, emblazoned with, “Women of the World Unite!”. The one day strike was a huge success, and NOW’s membership increased by 50% in the following months. At its peak in 1974, NOW could claim 40,000 members, a reflection of the fact that the Women’s Movement had truly acquired a mass character.

While NOW embraced a relatively radical program, it did not seek to challenge the capitalist system, but to win women an equitable place in it. In the interest of appearing acceptable to the “mainstream” of society, NOW’s leadership consciously pushed away radicals. It was clearly linked to a wing of the corporate Democratic Party.

Despite some campaigning on racial inequality, NOW had serious inadequacies in its approach to women of color, and the organization was overwhelmingly white.

NOW leader Betty Friedan infamously referred to radicalizing lesbian women as “the lavender menace”; lesbianism didn’t fit in with Friedan’s respectability politics. NOW’s refusal to fully take up racial and sexual diversity in organizing, and its focus on legal equality rather than a program addressing working women’s needs constituted a significant weakness for the entire women’s movement.

Women’s Liberation

For many of the young women who were involved in the anti-war and civil rights movements, the liberal feminism epitomized by NOW was not enough. The enormous radicalization of this period spurred women to explore a complete undoing of women’s roles in romantic relationships, in the family, in society, and in organizations of the left. The birth of women’s liberation groups can be traced to activist women’s experiences being sidelined politically and sexually objectified within certain “new left” organizations.

This was particularly true of the Students for a Democratic Society which failed to address widespread chauvinism in its ranks. This led a number of women in SDS to a more intense discussion about the deeper roots of women’s oppression and how to fight it. These types of debates were occurring among left wing activist women across the country, including in Black and Latino organizations. In the fall of 1967, a section of radical women began to form their own organizations, dedicated to the liberation of women. By 1969, there were women’s liberation groups in over 40 cities.

Women’s liberation organizations often started as consciousness-raising groups, where women gathered to discuss their common oppression and developed into activist groups that used direct action to campaign on reproductive rights, rape and the objectification of women. Activists overturned the taboo on talking about women’s sexuality and reproductive health, and lesbian women were welcomed into the movement.

Although the women’s liberation movement embraced a more global view of women’s experiences than the mainstream feminist movement, it too was dominated by middle class white women. Socialist-feminists within the movement never coalesced into a unified force that impacted the overall direction of women’s liberation. Separatist ideas of women organizing and even living separate from men was a trend within the women’s liberation movement, giving the media ammunition to smear it as “man-hating.” The movement’s failure to adopt a clear program that could speak to the interests and needs of working class women and women of color limited its appeal, even while its campaigns had a positive impact on popular opinion.

Winning the Right to Choose

NOW led the mainstream feminist push for abortion rights, becoming the first national organization to demand the abolition of all laws restricting abortion, and contributing to the establishment of the National Association for the Repeal of Abortion Laws (NARAL), which led the mainstream campaign for abortion rights.

NARAL worked with the rapidly growing women’s liberation movement to stage provocative events, such as speak-outs where women testified about their own abortion experiences. Debates against anti-abortion activists was another favored tactic of NARAL, and the organization produced materials giving advice on how to stage and win debates, and how to get maximum media coverage.

The Chicago Women’s Liberation Union, a socialist-feminist group whose many projects included the abortion-providing Jane Collective, staged a direct action at the American Medical Association’s convention, where activists infiltrated the event and presented a list of demands that included free, legal abortion. The women’s movement in New York won abortion rights after a sustained struggle including direct actions in 1970. Similar campaigns were erupting across the country and 14 states liberalized abortion laws to varying degrees prior to Roe v. Wade.

In Washington State, a group of physicians concerned about the threat of illegal abortions to women’s health managed to get an abortion initiative onto the state ballot in 1970. Two Seattle feminist organizations reframed the issue as a question of women’s liberation and built a grassroots movement to fight for every vote. Women’s Liberation Seattle produced and sold 10,000 copies of a pamphlet entitled “One in Four of Us Have Had or Will Have an Abortion.” Rallies and meetings were held all over the state and activists leafleted and door-knocked to get the word out. In the end, the initiative passed with 56% voting in favor of women’s right to an abortion.

The 1973 Supreme Court decision legalizing abortion nationwide, Roe v. Wade, was a historic victory for the women’s rights movement. In a sequence that bears similarity to the more recent struggle for marriage equality, a conservative Supreme Court tailed the mass movement and the resulting shift in popular attitudes on abortion. The Court, representing the interests of the ruling class, was forced by the movement into action if it wanted to avoid further mass radicalization.

Women and the Labor Movement

Working class women, mostly out of the spotlight in the organized feminist movement, charted their own path toward liberation, and they did it at their workplaces and in their unions. Women entered the workforce in large numbers in the ’60s and ’70s, and were part of a demographic transformation of the U.S. working class that also included new industries and job categories opening to black workers and other racial minorities.

Women in traditionally female occupations like domestic workers, office workers, hospital workers, and other service workers also moved into struggle, using collective action to fight for economic demands, including demands against the rampant workplace sexism present in many service sector female-dominated jobs. Working class women engaged in a feminist battle on their own terms, where the sexist, racist and paternalistic norms that governed workplace relations were challenged in a movement that was a major contributor to the growing rejection of traditional sexist attitudes about the role of women.

For example, the working conditions of flight attendants in the 1960s were a nightmare of female objectification: weekly weigh-ins with workers facing firing if they came in too high, maximum working age of 32 and advertising campaigns that practically invited passengers to sexually harass workers. Unionized female flight attendants ran into a wall when they tried to get their male union leadership to take action against sexism on the job. Clerical workers were viewed as low-paid “office wives” who were expected to fetch coffee and pick up lunch for male bosses. Both groups of workers created new organizations to protest their second class and often hypersexualized status in the workplace and both eventually organized new unions.

Flight attendants built Stewardesses for Women’s Rights (SFWR), which developed a wide-ranging campaign of protest, legal remedies and publicity with support from the mainstream feminist movement. Clerical workers set up organizations that held protests and lobbied the government over sex discrimination in hiring, pay and promotion. The flight attendants were particularly successful in using slow-downs, sick-outs and strike threats in conjunction with SFWR to end several of the most egregiously dehumanizing policies.

Domestic workers, who were overwhelmingly black, faced the double oppression of racism and sexism on the job, and were highly exploited with virtually no legal labor protections. Domestic workers’ organizations, such as the National Domestic Workers Union, often served many functions: campaigning against low pay and abusive practices, educating workers on their rights, placing workers in jobs and adjudicating grievances with employers. Despite the difficulties of organizing workers who were highly isolated, domestic worker organizations helped to win some federal legal protections and higher wages in certain regional markets.

The Revolutionary Potential of the 1970s

The overlapping movements of women in NOW, radical-feminist groups, and in workplaces coincided with dramatic and sustained upsurge in working-class militancy. In 1970, approximately one sixth of the 27 million unionized workers went out on strike. These workers were fighting for more than increased wages and greater benefits; teachers, overwhelmingly women, struck to improve classroom policies, and expand collective bargaining rights in the public sector. Coal miners, teamsters, and auto-workers struck en masse, while simultaneously organizing reform caucuses to wrest control of their unions back to the rank-and-file. Electrical, telephone, and railroad workers mobilized hundreds of thousands in strikes which brought major sections of industry to halt.

The labor revolt, combined with radical social movements against racism and sexism, and the revolt within the U.S. military in Vietnam was creating an increasingly ungovernable situation. The Watergate scandal and subsequent impeachment of Richard Nixon showed the chaos that enveloped the U.S. ruling class.

Tragically, however, the transformational potential of the 1970s remained unrealized. Working people, youth, women, people of color, and LGBTQ people were revolting against the establishment but their leaders failed to join together and build a new political party representing the interests of working people and all the oppressed to take on the capitalist-dominated political and economic system.

An early casualty of this failure was Nixon’s largely uncontested veto of legislation that would have created universal childcare in 1971. Despite women flooding into the job market, an organized mass women’s movement, and a rank and file led upsurge in the unions, no united effort was launched to fight the veto.

By 1975, the newly emerging family values far right seized ground on child care, painting it as communistic and un-American, as the backlash against the women’s movement developed. The Democratic Party also began heading to the right as the capitalists moved towards neo-liberal policies. The election of Ronald Reagan in 1980, and his firing of striking air traffic control workers a year later, signaled the beginning of several decades of defeats for unions, which the labor movement hasn’t recovered from.

Need for Marxist Leadership

Women’s experiences confronting the shockingly regressive attitudes in sections of the “new left” reflected the absence of a significant genuine Marxist current in the U.S. fighting for socialist feminist ideas.

At its best, the early American radical left was on the front lines of fighting for women’s rights, especially in organizing extremely exploited women workers. The Industrial Workers of the World and socialist activists like Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, for example, played a key role in the famous “bread and roses” strike of 1912 by immigrant women textile workers in Lawrence, Massachusetts. It was also the Socialist Party which organized the first Women’s Day march in 1909 in New York and inspired the Socialist International to adopt it as an international day of action for working class women the following year.

Revolutionary socialists including Marx and Engels saw the oppression of women as interwoven with the whole history of class society. They concluded that while fighting tooth and nail for every gain possible for working women today, full liberation could only be won by ending the rule of the capitalists.

Armed with a genuine Marxist program, tens of thousands of fighters for women’s liberation, black liberation and workers power could have joined together in the U.S. in the ‘70s to build a powerful revolutionary current in a broad mass workers party. The historic tasks of the women’s movement of the 1960s and 1970s remain to be completed: women continue to face obstacles in reproductive rights, employment, sexual violence and more. A new women’s movement is needed alongside a mass workers movement that based on the lessons of the past, challenges the capitalist system itself in a decisive fight for women’s liberation.

A new women’s movement is emerging in response to the election of the misogynist Donald Trump, starting with the 2017 women’s marches and now with the #MeToo campaign. The potential power of the #MeToo moment has so frightened the political class, the CEOs, the 1% investors, etc., that dozens of famous abusers have been fired or forced to resign. This is a victory, but women have much more to win.

A real pathway for workers to deal with abusive bosses and coworkers, whether your boss is famous or not, can be won, but it will require a mass movement that takes the streets and disrupts the status quo. The last major women’s movement in the U.S. during the 1960s and 1970s was a period of sustained mobilization around women’s issues that won important reforms and changed the attitudes of millions on women’s roles in society. It also showed the limitations of liberal and radical feminism.

The women’s movement of the 1960s and 1970s emerged during an era of massive social upheavals nationally and internationally. In the U.S., the determined struggle of African Americans in the Civil Rights movement had a transformative effect on the consciousness of millions of workers and youth. The movement against the war in Vietnam was enormous in scale, drawing an estimated 36 million to protests during 1969 alone. The establishment was being challenged from all sides, and women, people of color, LGBTQ people, and workers were emboldened to take their fight against oppression and inequality to higher levels of organization and action.

The Birth of NOW

The National Organization of Women, NOW, founded in 1966, developed a strategy and tactics to deliver full legal equality of women to men. Although NOW often campaigned for demands that would benefit all women, NOW policies were centered around the concerns of educated, middle class women and were sometimes at odds with working class women’s interests.

NOW was effective in winning reforms through a barrage of lawsuits combined with protests and mass actions, particularly in employment discrimination. It began by pushing for an end to sex-segregated job listings in newspapers, combining lobbying efforts with picketing and demonstrations which succeeded in ending the practice by 1968. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, the federal agency tasked with enforcing the Civil Rights Act rules against discrimination in employment, only began enforcing the law on sex discrimination after a NOW campaign forced the change.

On August 26, 1970, the National Women’s Strike saw tens of thousands of women strike all across the country around three central demands; the right to abortion, the right to childcare, and equal opportunity in employment and education. Demonstrations varied in character from city to city, but it was because of the existence of NOW that the Women’s Strike was a nationally coordinated action.

In New York City, fifty thousand women marched down 5th Avenue, and a banner was hung from the Statue of Liberty, emblazoned with, “Women of the World Unite!”. The one day strike was a huge success, and NOW’s membership increased by 50% in the following months. At its peak in 1974, NOW could claim 40,000 members, a reflection of the fact that the Women’s Movement had truly acquired a mass character.

While NOW embraced a relatively radical program, it did not seek to challenge the capitalist system, but to win women an equitable place in it. In the interest of appearing acceptable to the “mainstream” of society, NOW’s leadership consciously pushed away radicals. It was clearly linked to a wing of the corporate Democratic Party.

Despite some campaigning on racial inequality, NOW had serious inadequacies in its approach to women of color, and the organization was overwhelmingly white.

NOW leader Betty Friedan infamously referred to radicalizing lesbian women as “the lavender menace”; lesbianism didn’t fit in with Friedan’s respectability politics. NOW’s refusal to fully take up racial and sexual diversity in organizing, and its focus on legal equality rather than a program addressing working women’s needs constituted a significant weakness for the entire women’s movement.

Women’s Liberation

For many of the young women who were involved in the anti-war and civil rights movements, the liberal feminism epitomized by NOW was not enough. The enormous radicalization of this period spurred women to explore a complete undoing of women’s roles in romantic relationships, in the family, in society, and in organizations of the left. The birth of women’s liberation groups can be traced to activist women’s experiences being sidelined politically and sexually objectified within certain “new left” organizations.

This was particularly true of the Students for a Democratic Society which failed to address widespread chauvinism in its ranks. This led a number of women in SDS to a more intense discussion about the deeper roots of women’s oppression and how to fight it. These types of debates were occurring among left wing activist women across the country, including in Black and Latino organizations. In the fall of 1967, a section of radical women began to form their own organizations, dedicated to the liberation of women. By 1969, there were women’s liberation groups in over 40 cities.

Women’s liberation organizations often started as consciousness-raising groups, where women gathered to discuss their common oppression and developed into activist groups that used direct action to campaign on reproductive rights, rape and the objectification of women. Activists overturned the taboo on talking about women’s sexuality and reproductive health, and lesbian women were welcomed into the movement.

Although the women’s liberation movement embraced a more global view of women’s experiences than the mainstream feminist movement, it too was dominated by middle class white women. Socialist-feminists within the movement never coalesced into a unified force that impacted the overall direction of women’s liberation. Separatist ideas of women organizing and even living separate from men was a trend within the women’s liberation movement, giving the media ammunition to smear it as “man-hating.” The movement’s failure to adopt a clear program that could speak to the interests and needs of working class women and women of color limited its appeal, even while its campaigns had a positive impact on popular opinion.

Winning the Right to Choose

NOW led the mainstream feminist push for abortion rights, becoming the first national organization to demand the abolition of all laws restricting abortion, and contributing to the establishment of the National Association for the Repeal of Abortion Laws (NARAL), which led the mainstream campaign for abortion rights.

NARAL worked with the rapidly growing women’s liberation movement to stage provocative events, such as speak-outs where women testified about their own abortion experiences. Debates against anti-abortion activists was another favored tactic of NARAL, and the organization produced materials giving advice on how to stage and win debates, and how to get maximum media coverage.

The Chicago Women’s Liberation Union, a socialist-feminist group whose many projects included the abortion-providing Jane Collective, staged a direct action at the American Medical Association’s convention, where activists infiltrated the event and presented a list of demands that included free, legal abortion. The women’s movement in New York won abortion rights after a sustained struggle including direct actions in 1970. Similar campaigns were erupting across the country and 14 states liberalized abortion laws to varying degrees prior to Roe v. Wade.

In Washington State, a group of physicians concerned about the threat of illegal abortions to women’s health managed to get an abortion initiative onto the state ballot in 1970. Two Seattle feminist organizations reframed the issue as a question of women’s liberation and built a grassroots movement to fight for every vote. Women’s Liberation Seattle produced and sold 10,000 copies of a pamphlet entitled “One in Four of Us Have Had or Will Have an Abortion.” Rallies and meetings were held all over the state and activists leafleted and door-knocked to get the word out. In the end, the initiative passed with 56% voting in favor of women’s right to an abortion.

The 1973 Supreme Court decision legalizing abortion nationwide, Roe v. Wade, was a historic victory for the women’s rights movement. In a sequence that bears similarity to the more recent struggle for marriage equality, a conservative Supreme Court tailed the mass movement and the resulting shift in popular attitudes on abortion. The Court, representing the interests of the ruling class, was forced by the movement into action if it wanted to avoid further mass radicalization.

Women and the Labor Movement

Working class women, mostly out of the spotlight in the organized feminist movement, charted their own path toward liberation, and they did it at their workplaces and in their unions. Women entered the workforce in large numbers in the ’60s and ’70s, and were part of a demographic transformation of the U.S. working class that also included new industries and job categories opening to black workers and other racial minorities.

Women in traditionally female occupations like domestic workers, office workers, hospital workers, and other service workers also moved into struggle, using collective action to fight for economic demands, including demands against the rampant workplace sexism present in many service sector female-dominated jobs. Working class women engaged in a feminist battle on their own terms, where the sexist, racist and paternalistic norms that governed workplace relations were challenged in a movement that was a major contributor to the growing rejection of traditional sexist attitudes about the role of women.

For example, the working conditions of flight attendants in the 1960s were a nightmare of female objectification: weekly weigh-ins with workers facing firing if they came in too high, maximum working age of 32 and advertising campaigns that practically invited passengers to sexually harass workers. Unionized female flight attendants ran into a wall when they tried to get their male union leadership to take action against sexism on the job. Clerical workers were viewed as low-paid “office wives” who were expected to fetch coffee and pick up lunch for male bosses. Both groups of workers created new organizations to protest their second class and often hypersexualized status in the workplace and both eventually organized new unions.

Flight attendants built Stewardesses for Women’s Rights (SFWR), which developed a wide-ranging campaign of protest, legal remedies and publicity with support from the mainstream feminist movement. Clerical workers set up organizations that held protests and lobbied the government over sex discrimination in hiring, pay and promotion. The flight attendants were particularly successful in using slow-downs, sick-outs and strike threats in conjunction with SFWR to end several of the most egregiously dehumanizing policies.

Domestic workers, who were overwhelmingly black, faced the double oppression of racism and sexism on the job, and were highly exploited with virtually no legal labor protections. Domestic workers’ organizations, such as the National Domestic Workers Union, often served many functions: campaigning against low pay and abusive practices, educating workers on their rights, placing workers in jobs and adjudicating grievances with employers. Despite the difficulties of organizing workers who were highly isolated, domestic worker organizations helped to win some federal legal protections and higher wages in certain regional markets.

The Revolutionary Potential of the 1970s

The overlapping movements of women in NOW, radical-feminist groups, and in workplaces coincided with dramatic and sustained upsurge in working-class militancy. In 1970, approximately one sixth of the 27 million unionized workers went out on strike. These workers were fighting for more than increased wages and greater benefits; teachers, overwhelmingly women, struck to improve classroom policies, and expand collective bargaining rights in the public sector. Coal miners, teamsters, and auto-workers struck en masse, while simultaneously organizing reform caucuses to wrest control of their unions back to the rank-and-file. Electrical, telephone, and railroad workers mobilized hundreds of thousands in strikes which brought major sections of industry to halt.

The labor revolt, combined with radical social movements against racism and sexism, and the revolt within the U.S. military in Vietnam was creating an increasingly ungovernable situation. The Watergate scandal and subsequent impeachment of Richard Nixon showed the chaos that enveloped the U.S. ruling class.

Tragically, however, the transformational potential of the 1970s remained unrealized. Working people, youth, women, people of color, and LGBTQ people were revolting against the establishment but their leaders failed to join together and build a new political party representing the interests of working people and all the oppressed to take on the capitalist-dominated political and economic system.

An early casualty of this failure was Nixon’s largely uncontested veto of legislation that would have created universal childcare in 1971. Despite women flooding into the job market, an organized mass women’s movement, and a rank and file led upsurge in the unions, no united effort was launched to fight the veto.

By 1975, the newly emerging family values far right seized ground on child care, painting it as communistic and un-American, as the backlash against the women’s movement developed. The Democratic Party also began heading to the right as the capitalists moved towards neo-liberal policies. The election of Ronald Reagan in 1980, and his firing of striking air traffic control workers a year later, signaled the beginning of several decades of defeats for unions, which the labor movement hasn’t recovered from.

Need for Marxist Leadership

Women’s experiences confronting the shockingly regressive attitudes in sections of the “new left” reflected the absence of a significant genuine Marxist current in the U.S. fighting for socialist feminist ideas.

At its best, the early American radical left was on the front lines of fighting for women’s rights, especially in organizing extremely exploited women workers. The Industrial Workers of the World and socialist activists like Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, for example, played a key role in the famous “bread and roses” strike of 1912 by immigrant women textile workers in Lawrence, Massachusetts. It was also the Socialist Party which organized the first Women’s Day march in 1909 in New York and inspired the Socialist International to adopt it as an international day of action for working class women the following year.

Revolutionary socialists including Marx and Engels saw the oppression of women as interwoven with the whole history of class society. They concluded that while fighting tooth and nail for every gain possible for working women today, full liberation could only be won by ending the rule of the capitalists.

Armed with a genuine Marxist program, tens of thousands of fighters for women’s liberation, black liberation and workers power could have joined together in the U.S. in the ‘70s to build a powerful revolutionary current in a broad mass workers party. The historic tasks of the women’s movement of the 1960s and 1970s remain to be completed: women continue to face obstacles in reproductive rights, employment, sexual violence and more. A new women’s movement is needed alongside a mass workers movement that based on the lessons of the past, challenges the capitalist system itself in a decisive fight for women’s liberation.