A left-wing alternative to the two sides in dispute, based on a anti-imperialism, class struggle and socialism is urgently needed

In power since 2013, Nicolás Maduro took office on 10 January for his third term as president of Venezuela. The inauguration took place despite the fact that Venezuela’s National Electoral Council had still not effectively refuted the allegations of fraud in the elections on 28 July, still failing to release records from electronic ballot boxes.

Immediately after the elections, strong indications of fraud and huge popular dissatisfaction after years of severe economic and social crisis, led to huge protests. They were strongly repressed by the state, causing at least 25 deaths and around 2,000 arrests.

The ultra-right opposition, led by Presidential candidate Edmundo González Urrutia and his main supporter, María Corina Machado, tried to manipulate popular dissatisfaction to accumulate forces for project: a reactionary coup. Failing to achieve his goal, Edmundo González ended up leaving the country in September and moving to Spain.

In the days leading up to Maduro’s inauguration, González visited ultra-right-wing allies in Latin America, such as Javier Milei in Argentina, and was received by Joe Biden in Washington. He even announced that he would return to Venezuela to take office. The ultra-right opposition also tried to mobilise its forces in the country to prevent Maduro’s inauguration.

Meanwhile, in the Colombian city of Cúcuta, on the border with Venezuela, Colombia’s far-right ex-president Álvaro Uribe made waves when he called for a military intervention to overthrow Maduro. Demonstrations were called by the ultra-right and new calls were made for sections of the armed forces to break with the regime. But that didn’t stop Maduro from taking office.

Surrounded by a strong repressive apparatus, the inauguration ceremony took place amid street mobilisations, both for and against Maduro, which were much smaller than those that took place after the elections last year.

Maduro and Latin American ‘Progressive’ governments

While just two heads of state — Díaz-Canel from Cuba and Daniel Ortega from Nicaragua — attended Maduro’s inauguration, they were joined by official representatives from elsewhere. These included both countries that have supported Maduro from the start (such as Russia, China, Bolivia and Honduras), and those that have not officially recognised Maduro’s victory, such as Brazil, Colombia and Mexico.

2024 was the first time that governments considered “progressive” in Latin America have also raised questions about the election results in Venezuela. While they have still not recognised the announced result, they also haven’t necessarily recognised a victory for the ultra-right opposition either.

Last year, the governments of Brazil, Colombia and Mexico sought a negotiated solution to the Venezuelan political crisis, but failed, and tensions continued to exist. The Brazilian government, for example, vetoed Venezuela’s entry into the BRICS alliance at the bloc’s meeting in Kazan (Russia) last October and mutual accusations were publicly exchanged between Maduro and Lula.

The stance of the Brazilian government, as well as that of other so-called “progressive” governments, reflects in the first place an attempt to avoid the domestic political damage of having to defend the Venezuelan regime in the face of attacks from right-wing forces. Instead of presenting a consistent left-wing, socialist or radically democratic alternative to the Maduro regime, they are capitulating to the discourse of US imperialism and the extreme right.

Moreover, if this can be observed in the case of Lula, with some oscillations, it is even more evident in the complete capitulation to US imperialism and the local right-wing sectors of governments like Gabriel Boric’s in Chile, the most forceful against Maduro among those who were considered “progressive” when elected.

In Lula’s case, distancing himself from Maduro also reflects illusions in a project that aims to balance between the forces in dispute. On this basis, Lula tries to position himself as a great negotiator of the conflicts in Latin America and between the imperialist blocs.

This supposed “non-alignment,” however, is not built on the basis of an alternative left-wing, internationalist, anti-imperialist and anti-capitalist project. It is the continuation in foreign policy of a policy of class conciliation that is applied internally, and with terrible results, it must be said.

Trump and Venezuela

Ten days after Maduro’s inauguration, Donald Trump began his second term in Washington, adopting all the predictable imperialist arrogance and aggressiveness. Based on the experience of Trump’s first term, it would be perfectly reasonable to expect an immediate hardening of relations with Venezuela.

In 2019, during his first term, Trump sponsored the farce of recognising Juan Guaidó (former head of the Venezuelan National Assembly) as the country’s self-proclaimed president. A large part of Venezuelan assets in the US were confiscated and began to be managed by the ultra-right-wing opposition, and harsh economic sanctions were adopted against Venezuela.

At the time, Trump, together with the Venezuelan far right, encouraged plans for a coup d’état in the country. He did not even rule out a military incursion that could have counted on the participation of the far-right governments that existed at the time in Colombia (Iván Duque) and Brazil (Bolsonaro).

This coup project failed, but the dangers of Trump 2.0 cannot be underestimated, and not just in the case of Venezuela, but of Latin America as a whole. Even so, in order to be able to organise resistance to US imperialism in a consistent way, it is necessary to try to understand the meaning of the contradictory signals sent by the White House in recent weeks, as well as the contradictions of the Maduro regime itself. This must go alongside an understanding of the strategic interests and objectives at stake in the international scenario that has evolved since Trump’s first term.

Given the weight that the Chinese economy has in Latin America today and in the context of the inter-imperialist dispute between China and the US, there is no doubt that Trump 2.0 represents the continuity of the defence of US imperialist interests in Latin America “by any means necessary.”

However, in this new guise of a “Monroe Doctrine” for the 21st century (read Latin America for the Americans against the Chinese advance in the region), we must try to understand how Trump’s “big stick” will be combined with elements of negotiation and soft power, counting on the capitulation of Latin American governments.

Trump’s special envoy to Caracas

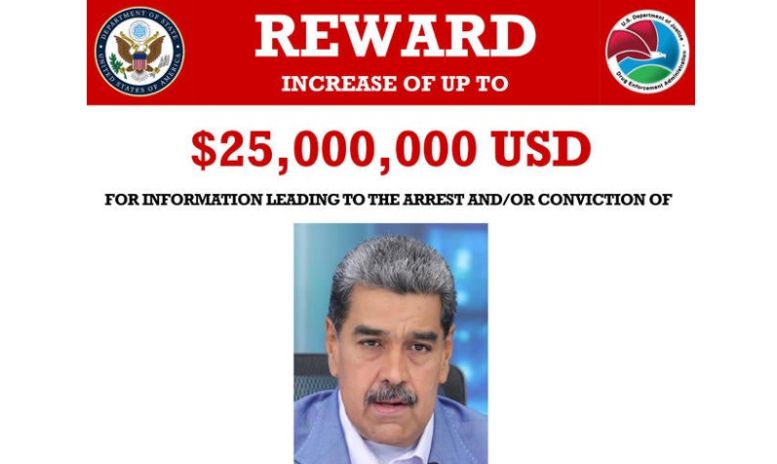

On the day Maduro took office, the US announced that it would increase to 25 million dollars the reward for any information that could lead to Maduro’s arrest. A few days later (20 January), however, Richard Grenell, former Director of National Intelligence in the first Trump administration and now US government envoy for special missions in Venezuela and North Korea, declared on ‘X’ that he was in contact with Venezuelan authorities.

“Diplomacy is back,” Grenell wrote, before concluding by saying that “talking is a tactic”. After meeting with Trump the previous day, Grenell disembarked from a military plane on 31 January at Simón Bolívar airport in Maiquetía, near Caracas.

Trump’s envoy was received with pomp and circumstance at Miraflores Palace by Nicolás Maduro, who has since characterised the visit as recognition by the US government of his de facto legitimacy.

Although Grenell himself had already secretly met with Venezuelan officials in Mexico City in 2020, this was the first formal and public contact between a Trump representative and Maduro at the seat of the Venezuelan government since the farce surrounding Guaidó began in 2019.

Maduro declared that he proposed to the US representative to agree “agenda zero” in relations between the two countries — a resumption of dialogue without preconditions or impositions. Publicly, however, Grenell and the White House limited themselves to justifying the meeting with Maduro by obtaining the release of six US citizens imprisoned in Venezuelan jails on terrorism charges.

Grenell also announced that, on the basis of the dialogue, Venezuela would agree to receive Venezuelan immigrants deported from the US, fly them on Venezuelan planes and pay for the flights. Two weeks later, the first planes of the state-owned Conviasa (previously subject to US sanctions) took off from El Paso (Texas) with 190 Venezuelan deportees.

Deportations of Venezuelans

The mass deportation of Latin American immigrants, amid xenophobic and racist rhetoric, was a central theme of Trump’s campaign and is one of the horrific hallmarks of his first days in office.

In the case of Venezuelan immigrants, Trump’s stance has changed. At the end of his first term and in the midst of the 2020 election campaign, Trump adopted measures to protect immigrants from that country. Building a right-wing social base among Venezuelan-Americans, especially in Florida (similar to Cuban-Americans) was one of his objectives. Welcoming Venezuelans to the US who were escaping the “hell” of the Maduro regime was part of his aggressive campaign against the Venezuelan government.

What we’re seeing now, however, is the exact opposite. The anti-immigrant campaign is a central part of Trump’s rhetoric and in the case of Venezuelans, all the scaremongering about the role of criminal groups with origins in that country, such as the Tren de Aragua,” play an important role in his racist and xenophobic policies. Among the 600,000 or so Venezuelans in the US, around 360,000 will be immediately affected by the new government’s decision to end their temporary protection status (TPS).

Unlike the (at least rhetorical) protests by some “progressive” Latin American presidents, such as Gustavo Petro of Colombia, against the truculent and inhumane way in which the deportations were taking place, Maduro reacted in a totally collaborative way with Trump.

Along with a cynically optimistic speech about the future of the new arrivals back in Venezuela, Maduro tried to use the deportees as a bargaining chip. He argued that the lifting of economic sanctions would solve the migration problem that the US and other countries in the region have with the influx of Venezuelans.

Edmundo González, meanwhile, criticised the negotiations between the Trump administration and Maduro over the fate of Venezuelan immigrants. Without condemning the deportations, González even suggested that the deported Venezuelans should be sent to countries other than Venezuela.

At the moment, there are already many Venezuelans, many of them unidentified, who have been sent to detention camps for deportees at the US military base in Guantánamo. The ultra-right-wing president of El Salvador, Nayib Bukele, has also offered his prisons to US deportees.

The total Venezuelan diaspora resulting from the deep crisis of the last decade (also aggravated by the sanctions) amounts to around 8 million people, according to the UNHCR. No solution will come without confronting the fundamental logic of peripheral and dependent capitalism in Latin America and the role of imperialism. The defence of the rights of Latin American immigrants in the US is a struggle of the working class of the entire continent and must be linked to a class struggle and socialist perspective.

Politics and oil

As important as the migration problem is for both countries, it’s not the only thing that explains Trump’s stance on Venezuela. The issue of oil and the US’s strategic interests in energy are also on the table.

On his visit to Caracas, Grenell didn’t pay much attention to the ultra-right opposition. María Corina Machado tried not to appear excluded from the US initiative and, according to reports, even contacted Marco Rubio, the new Secretary of State.

Trump’s special envoy, contrary to María Corina Machado’s expectations, gave no indication of any changes to the licences given by the US Treasury Department to oil companies, especially Chevron, to operate in Venezuela, despite the sanctions that remain in force against the country.

At the end of 2023, the Biden administration suspended a substantial part of the sanctions against Venezuela within the framework of the Barbados agreements, signed in October this year between the government and the ultra-right opposition, with the aim of guaranteeing “competitive” elections.

The licences for Chevron and other oil companies had already been in place since the start of the 2022 negotiations. Not a minor factor in this change of course on the part of US imperialism was the consequences of the war in Ukraine (which began the same year) for energy supplies in the US and Europe.

With the resurgence of political tensions in Venezuela in April 2024 and the questioning of the 28 July election result, most of the sanctions were reimposed, but individual licences for oil companies operating in the country were automatically granted and renewed.

Chevron’s weight, in particular, is significant in a Venezuelan economy marked by sanctions and crisis. The company is responsible for 20 percent of national oil exports and 31 percent of the government’s total oil revenue, according to industry analysts.

Chevron currently extracts almost 300,000 barrels a day in Venezuela. Last December, Chevron’s export volume reached a six-year high and doubled compared to the same month in 2023. The company operates in partnership with PDVSA (the Venezuelan state oil company) and is present in the exploitation of the Orinoco oil belt, the largest known crude oil reserve in the world.

For the Maduro government, the presence of Chevron and other companies in the country is part of its policy of economic liberalisation, privatisations, the withdrawal of workers rights and all kinds of political and economic regression implemented in recent years.

A socialist policy for confronting the crisis, sanctions and imperialist attacks means confronting the bourgeoisie and moving decisively in the direction of effective workers’ power over the state and the economy, based on mass mobilisation and organisation and active international solidarity. Instead, the Maduro government has followed the path of economic and social counter-reforms, attempts at reconciliation with US imperialism, harsher internal repression, and a deepening financial and military dependence on the imperialist bloc headed by China and Russia.

Chevron’s licence to operate in Venezuela is reviewed every six months. It was confirmed in October, despite the US not officially recognising Maduro’s victory. A new review will take place in April. The licence could have been suspended immediately after Trump’s inauguration if that had been his wish, but that hasn’t happened and there are no signs that it will.

Different approaches of imperialism

There is a difference in form, emphasis and content between Grenell’s speeches and stances today and the stance always adopted by Marco Rubio. The new Secretary of State is a notorious representative of the ultra-right hard line on US imperialist policy in Latin America.

Although he has relatively moderated his line in the last period, he continues to represent a more aggressive wing of US imperialism. On the eve of Trump’s inauguration, the then nominee for the State Department criticised Biden for having “allowed himself to be deceived” in the negotiations with Maduro. He even said that the licences for Chevron needed to be re-examined because these companies were ‘contributing billions of dollars to the Venezuelan regime’s coffers.

An example of the apparent disagreement within the US new administration (or the conscious decision to send out contradictory signals) was Rubio’s decision, even in the midst of ongoing negotiations between the US government and Maduro over deportations, to seize a Venezuelan presidential plane that had been impounded in the Dominican Republic during his visit to that country.

With regard to Venezuela, Rubio’s priority is regime change via external pressure and encouraging the ultra-right-wing domestic opposition. This contrasts with the more pragmatic stance represented by Richard Grenell, who tends to recognise the limits of the Venezuelan opposition’s chances of victory and prefers to negotiate with the Maduro regime itself for immediate and future gains. A dynamic and oscillating combination of these two stances tends to be the policy adopted by Trump.

A more belligerent alternative policy, which includes some kind of direct or indirect military intervention, is still ever-present among the options and scenarios under consideration by US imperialism. Disappointment with the failure of the attempts to defeat Maduro through sanctions on the one hand and negotiations on the other, leads some sectors of US imperialism to explicitly advocate that the US reproduce in Venezuela something similar to the stance adopted towards Panama in January 1990. Back then, an invasion by US troops overthrew the then president Manuel Noriega, a former US ally who fell out of favour with imperialism.

This path is not the most likely today. A direct military intervention in Venezuela would have far greater and more serious repercussions for the country and Latin America than in Panama in 1990, and could plunge the US into yet another difficult quagmire, the exact opposite of what Trump wants. However, the aggressiveness of US imperialism should never be underestimated in a context of polarisation, radicalisation and deepening inter-imperialist disputes.

A left-wing alternative to the two sides in dispute

Amid the great political impasse of Venezuela today, neither of the two sides at the centre of the dispute has the legitimacy to claim to represent democratic rights and respect for the people’s decision.

Maria Corina Machado denounced Maduro’s inauguration for a third term as a coup d‘état. But this right-wing opposition is largely the same as that which promoted the coup against Hugo Chávez in 2002, the oil lockout in 2003 and an almost total electoral boycott for several years. These are the same pro-coup sectors that promoted the farce of recognising the self-proclamation of Juan Guaidó as president of the country and advocated US military intervention in Venezuela, as well as harsh economic sanctions and the confiscation of the country’s reserves and assets abroad.

Nothing good for the Venezuelan people can come from these sectors and no illusions in them can be encouraged. But this does not justify ignoring the enormous political, social and economic setbacks promoted by Nicolás Maduro. Taking power after the illness and death of Hugo Chávez, Maduro symbolises the period of deepest political degeneration and attacks on the social gains won by the Venezuelan workers and people during the so-called Bolivarian revolution.

The basis of this degeneration is not explained simply by Maduro’s stance, but also by the limits of Chavismo itself, despite the revolutionary strength and willingness shown by broad sectors of the Venezuelan working class and poor people over the years.

The advance of a revolutionary process in Venezuela, confronting imperialism and guaranteeing social conquests and rights, would require the adoption of a consistent socialist program, guaranteeing effective workers’ control over the key sectors of the economy and the institutions of political power. The so-called Bolivarian revolution stopped halfway through, without destroying the foundations of dependent and peripheral Venezuelan capitalism. And, as we know, what doesn’t move forward ends up moving backwards.

Faced with a scenario of extremely serious economic and social crisis due to internal and external factors, as well as imperialist attacks, Maduro’s government, in order to survive, has relied fundamentally on the weight of the bureaucratic and military apparatus and on concessions and alliances with sectors of the Venezuelan and international bourgeoisie that are complacent about his regime.

The biggest attacks on democracy by the Maduro regime are not necessarily the measures taken against the coup and pro-imperialist ultra-right. Of greater importance are the attacks, arrests and persecution — under the guise of fighting “agents of the right” — which the government unleashes on the independent workers’ movement and on sectors of the left that dare to criticise the right-wing course adopted by the government, including sectors of so-called “critical chavismo.”

As a result of a conscious and deliberate action by the regime, no left-wing alternative was able to present itself in the last presidential elections, although there is a social basis for a left-wing opposition to Maduro.

Building the political and social forces of a new socialist and revolutionary left rooted in this social base, which is anti-imperialist and does not accept Maduro’s attacks, is an essential task in the struggle to return to the path of the Venezuelan revolution.