“Strong man” rule is spreading in this period of capitalist nationalism and militarism. Orban in Hungary, Yoon in South Korea, Erdogan in Turkey and now of course, above all Donald Trump wield state power in their own interests, undermining and directly jettisoning “democratic” norms, without consultation with parties or parliament.

France from 1848 to 1852, when a period of revolution, class struggle, repression, flailing “democrats” and populism ended in a bonapartist dictatorship, holds important lessons for today.

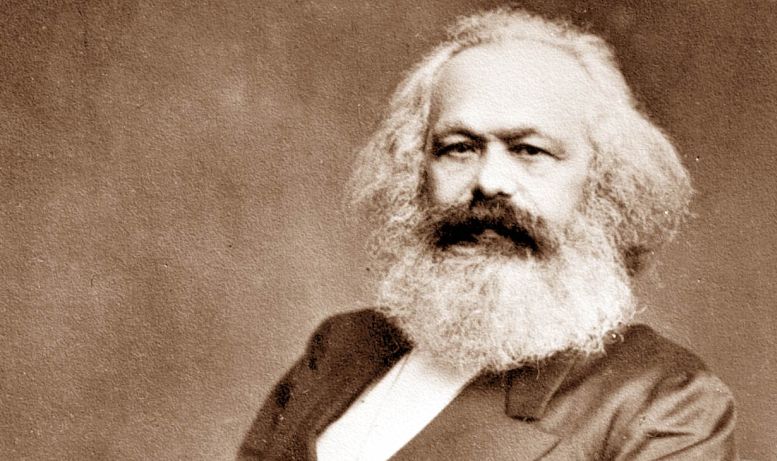

Karl Marx’s book The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte offers an incredibly clear-sighted analysis of these events and how a mediocre “strong man” came to power in a society at an impasse.

Revolutions are invariably followed by counter-revolutions aiming to restore the old system or at least parts of it. This is more marked than anywhere else in the history of France, following the great French revolution, the bourgeois revolution par excellence, which began in 1789.

This was a revolution, Marx explains, with the “task of breaking all separate local, territorial, urban, and provincial powers in order to create the civil unity of the nation”, which was necessary to pave the way for capitalist economic development. It was only possible through the mass action of the incipient working class, the sans culottes, which allowed the bourgeoisie (the capitalist class) to take power and which, through its most determined layers, moved the revolution forward.

In 1799, Napoleon Bonaparte took power in a coup, establishing himself as emperor, and led a brutal one-person dictatorship. But while many of the most far-reaching radical measures of the French Revolution were rolled back, the economic gains of the bourgeois revolution remained in place: ending feudalism and establishing capitalism as the dominant system. Through wars across much of the European continent, the revolution’s gains were also spread beyond France.

Napoleon lost power in 1815, and the conservative Bourbon monarchy, based on the landlords, returned to power but did not overturn capitalist property relations. Then in the 1830 revolution, another wing of the royal family (the Orleans) took the throne, relying on the financial and industrial wing of the bourgeoisie. Its unstable rule paved the way for the revolution of 1848.

Revolution 1848

The main force in the revolution 1848 was the growing working class. From France, it spread into a series of revolutions around Europe, shaking the ruling classes. In Paris, a provisional bourgeois government was formed, still under strong pressure from the proletariat. An occasional Republican leader, Raspail, “commanded the Provisional Government to proclaim a republic; if this order of the people were not fulfilled within two hours, he would return at the head of 200,000 men.”

As a result, a “social republic” was formed. However, it immediately sought to disarm and crush the working class. The workers were provoked by the new National Assembly and attempted to retake the initiative, first in May by storming parliament and then in the “June Days” with “the tremendous insurrection in which the first great battle was fought between the two classes that split modern society” (Karl Marx in The Class Struggles in France, 1848 to 1850). It took the army and the National Guard five days to defeat the workers, killing 3,000 in a massacre and deporting 15,000. Workers’ leaders were sent to prison, with the most well-known, Louis Blanqui, sentenced to 10 years. The working-class movement was pushed back for decades.

Giving this background, Marx explained, is the only way to “demonstrate how the class struggle in France created circumstances and relationships that made it possible for a grotesque mediocrity to play a hero’s part. Hegel remarks somewhere that all great world-historic facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce”.

“Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past.“

In other words, the development leading to Bonaparte’s dictatorship was neither inevitable nor a result of the actions of a clever individual.

By disarming the working class, relying on the force of the army, neglecting any democratic rights, the democratic bourgeoisie started the journey towards dictatorship.

Reversal of the revolution

All reactionary and bourgeois forces stood against the working class, Marx explained: “During the June days all classes and parties had united in the party of Order against the proletarian class as the party of anarchy, of socialism, of communism. The watchwords of the old society, “property, family, religion, order.”

Instead of moving the revolution forward, as from 1789 to 1815, 1848 represented a reversal. “In the June days of 1848, bourgeoisie and petty bourgeoisie had united as the National Guard with the army against the proletariat; on June 13, 1849, the bourgeoisie let the petty-bourgeois National Guard be dispersed by the army; on December 2, 1851, the National Guard of the bourgeoisie itself had vanished, and Bonaparte merely registered this fact when he subsequently signed the decree for its disbandment.” General Cavaignac, who led the massacre in June, established himself as dictator.

The reactionary propaganda against the proletariat started to hit the democratic and liberal wings of the bourgeoisie. “Every demand of the simplest bourgeois financial reform, of the most ordinary liberalism, of the most formal republicanism, of the most shallow democracy, is simultaneously castigated as an ‘attempt on society’ and stigmatized as ‘socialism.’”, Marx concluded: “What the bourgeoisie did not grasp, however, was the logical conclusion that its own parliamentary regime, its political rule in general, was now also bound to meet with the general verdict of condemnation as being socialistic.”

The bourgeoisie was split between two royalist wings, supporting one king pretender each, and republicans, or democrats. The latter, “busy devising, discussing, and voting” a new constitution, were the first to lose all power. While talking about democratic rights, they did not object to the massacre in June or Paris being under military rule from June to December 1848. When the united monarchists in the “party of Order” turned against them, they did not fight back.

President

Louis Bonaparte, the nephew of Napoleon, won the presidential elections in December 1848. He was the only well-known candidate, and the different bourgeois factions were sure they could control him. Marx describes his victory as “a reaction of the country against the town”, with large support in the army and among the monarchists. Even many workers and the petty bourgeoisie thought he would be a counterweight against Cavaignac.

As president, he formally controlled the army and nominated the government’s ministers. Initially, he did not intervene in the debates of the Assembly between different wings of the bourgeoisie and had no problem with their verbal criticism of him or his ministers. Of course, he supported every step towards suppressing democratic opposition.

The opposition in parliament was the Montagne, a social democratic party with a base among workers, including some self-proclaimed socialists and the petty bourgeoisie. In the legislative elections in spring 1849 it won all deputies in Paris. In June, however, they were crushed, with their leaders going into exile.

Marx explains how their program aimed to weaken the antagonism between workers and capital, striving for harmony. In June, it was provoked by Bonaparte when he broke with the constitution in a military adventure against Rome. The Montagne talked about armed struggle, but mobilised for a peaceful demonstration in favour of the constitution, believing it would be supported by the National Guard. However, as Marx commented, “If the peaceful demonstration was meant seriously, then it was folly not to foresee that it would be given a warlike reception.”

This was an important victory for Bonaparte, and the monarchists in the party of Order accepted the repression of the Montagne parliamentarians. Those in the National Guard supporting Montagne were exiled.

Populism and pre-fascism

Bonaparte encouraged the growing discontent with the political parties, the Assembly and “Paris”. He made clear “his opposition to the National Assembly, and to hint at a secret reserve that was only temporarily prevented by conditions from making its hidden treasures available to the French people”. Following this, he populistically proposed more pay to officers and possibilities for workers to take loans.

Bonaparte also toured the countryside with his populist campaign, “On his journeys the detachments of this society packing the railways had to improvise a public for him, stage popular enthusiasm, roar Vive l’Empereur, insult and thrash republicans, under police protection, of course.” Populism is filling a political vacuum, when there is a lack of a labour and left movement from below.

He prepared for a final fight, in contrast to the party of Order who hoped to avoid a confrontation with him. “Bonaparte, who precisely because he was a bohemian, a princely lumpen proletarian, had the advantage over a rascally bourgeois in that he could conduct the struggle meanly.” Marx explains how Bonaparte organised the “Society of December 10,” a prototype of a fascist organisation based on the lumpenproletariat in Paris, ruined bourgeoisie individuals, criminals, etc. It was secretly organised, numbering ten thousand. This private army of his was formally, but not in reality, disbanded.

Bonaparte’s populist maneuvers also included a “the Gold Bars Lottery”, a scam from which he earned millions.

The last straw

The party of Order, a coalition of monarchists, went from seemingly full control to losing everything to Bonaparte, without a fight. They accepted his words about peace and calm, and ignored growing warnings about a coup. They sent a delegation to convince Bonaparte not to dismiss the general Changarnier, who they hoped was on their side. But as Marx said “Whomever one seeks to persuade, one acknowledges as master of the situation”. Bonaparte of course discharged Changarnier.

Before that, they repeatedly refused to mobilise the masses, who in several elections kept voting for the most revolutionary candidates. To this, Bonaparte responded by abolishing the right to vote for three million people. The working class, without leadership and still suffering from the impact of the defeat of the 1848 revolution, generally followed the democrats and there was no struggle.

In 1851, Bonaparte was assisted by an economic downturn and increased unemployment. This was blamed on the politicians, and the bulk of the bourgeoisie, in finance and industry, became supporters of Bonapartism. Likewise the bourgeois representatives in towns and cities he toured. The party of Order merely campaigned to not revise the constitution, according to which Bonaparte could not be elected again, while the big bourgeoisie ”declared almost unanimously for revision, and thus against parliament and in favor of Bonaparte.”

The bourgeoisie also joined Bonaparte in sharp criticism and attacks on the press, first forcing revolutionary papers to close down, then its own bourgeois press.

Bonapartism

The bourgeoisie had again and again warned of the “red danger” — a terror regime led by the proletarian masses. Instead they got the coup of Bonaparte, on the night of 2 December 1852, which saw “the eminent bourgeois of the Boulevard Montmartre and the Boulevard des Italiens shot down at their windows by the drunken army of law and order”. Troops were on streets and leading politicians were imprisoned. The leaders of the working class were already in prison, which together with the defeat in June 1848 explained why there was no opposition from the masses.

The impasse of society was clearly expressed when “after the coup d’état the French bourgeoisie cried out: Only the Chief of the Society of December 10 can still save bourgeois society! Only theft can still save property; only perjury, religion; bastardy, the family; disorder, order!”

Louis Bonaparte became Napoleon III, a strong man, a one person dictatorship. He was the representative of bourgeois capitalist society, but even more so of the conservative peasants, a big share of the French population. The peasants were squeezed by capitalist landowners and banks, but kept hope that Bonaparte would save them.

As head of the huge state apparatus, with half a million in the army and half a million officials, Bonaparte portrayed himself as independent. “Bonaparte knows how to pose at the same time as the representative of the peasants and of the people in general, as a man who wants to make the lower classes happy within the framework of bourgeois society”, hoping to “appear as the patriarchal benefactor of all classes. But he cannot give to one without taking from another”.

In the final analysis, Bonaparte represented the capitalists, including internationally, illustrated by Marx in this way: “In its issue of November 29, 1851, the Economist declares in its own name: ‘The President is the guardian of order, and is now recognized as such on every stock exchange of Europe.’”

The trajectory of the bourgeois, democrats and monarchists, was summarised by Marx:

“It destroyed the revolutionary press; its own press is destroyed. It placed popular meetings under police surveillance; its salons are placed under police supervision. It disbanded the democratic National Guard, its own National Guard is disbanded. It imposed a state of siege; a state of siege is imposed upon it.”

The return of the old

Napoleon III, also known as the stupidest man in Europe, came to power as a result of social forces, of class struggle. His name in itself, Bonaparte, gave him status and a reputation as a saviour. When the leadership of the main social classes failed to resolve the social impasse, the emperor-strong man became an attractive solution.

For France it meant a return to the old. Marx described it as “the old dates arise again — the old chronology, the old names, the old edicts, which had long since become a subject of antiquarian scholarship, and the old minions of the law who had seemed long dead”. So “…it seems that the state has only returned to its oldest form, to a shamelessly simple rule by the sword and the monk’s cowl.”

However, with the state at the centre of his rule, Napoleon III continued to pretend to represent all classes. He combined some limited reforms to check the risk of class struggle with an aggressive colonial policy to benefit French capitalism and imperialism.

Eventually he lost the war against Prussia in 1870 and was forced into exile. The Prussian occupation in turn led to the revolutionary uprising of the working class in Paris. The Paris commune, with the working class holding power for two months, was a shining example that gave lessons to Marx and the Bolsheviks.

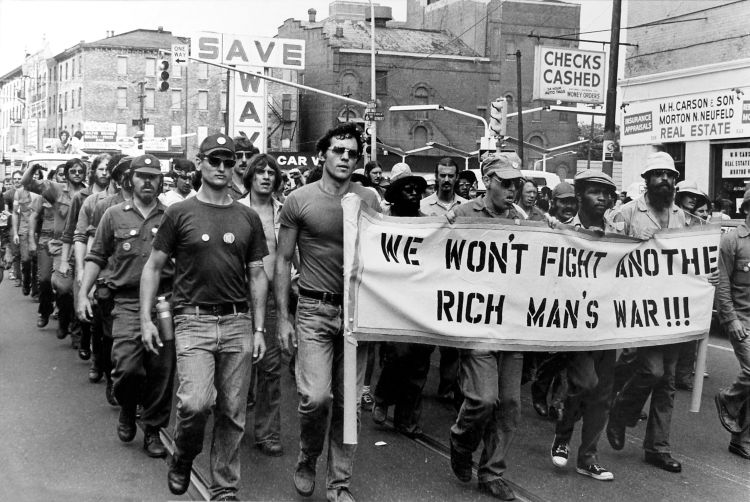

The events of revolution and counter-revolution in France 175 years ago hold important lessons also for today, while understanding the differences is also crucial. The most important lesson is the role of the working class. The different bourgeois wings could only achieve change through revolutionary action by the working masses. Fearing the revolution would go further, disarming the proletariat politically and physically then became a priority for the liberal democrats, republicans and monarchists alike. But without the masses, they could not defeat Bonaparte.

Louis Bonaparte (Napoleon III) was able to become emperor only on the basis of major defeats for the working class. In the US, Hungary and South Korea today, the working class today has not suffered such defeats as in France 1848, and the strong men do not have the power of Napoleon III. However, the threat of repression and attacks from the state on democratic rights and living standards are real. Socialists today need to study history, emphasising the decisive role of the working class and all oppressed against authoritarian rule, linking this struggle to the fight for socialism to replace the crisis-ridden rapidly militarising capitalist and imperialist system.