Darragh O’Dwyer is a member of Socialist Alternative (England, Wales & Scotland).

The Peruvian masses must rely on their own strength and continue to build local committees of struggle to unite workers, campesinos and Indigenous people and allow them to democratically discuss and coordinate the next steps of the movement.

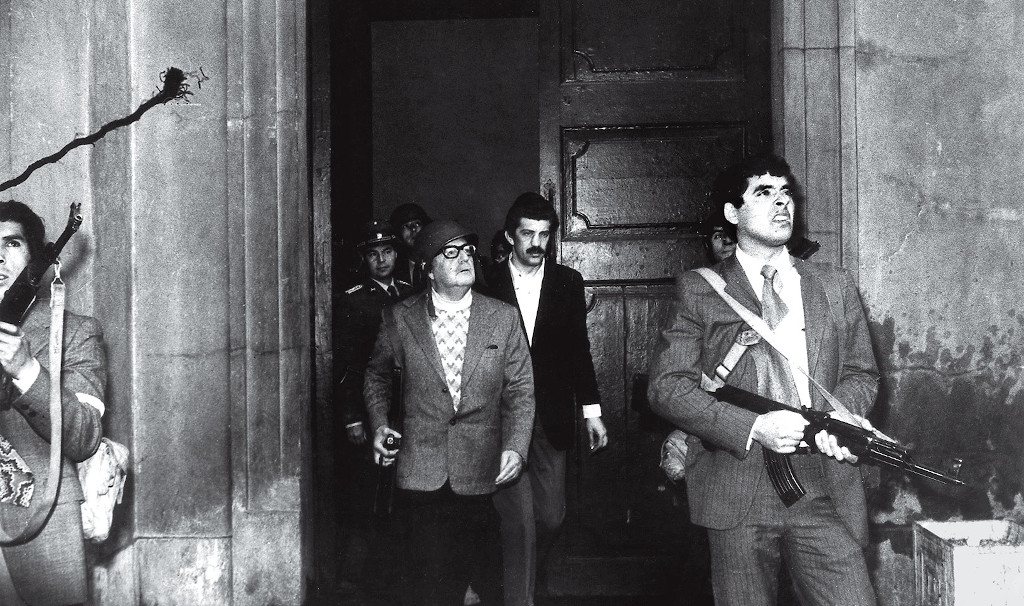

2022 came to a chaotic close in Peru. When former president Pedro Castillo attempted to dissolve congress and install a ‘government of exception’, he was removed as president and arrested in a parliamentary coup backed by the entire Peruvian oligarchy. In response, a mass movement of workers, poor and indigenous people has erupted demanding Castillo’s release, the resignation of the illegitimate President, Dina Boularte, and the calling of new elections.

Small protests began almost immediately after Castillo’s impeachment but quickly gathered momentum. Although Boularte initially stated her intent to remain in power until 2026, she backtracked and moved elections forward to 2024, a concession that failed to deter the movement. After early clashes with Peruvian state forces, the coup government announced a month-long state of emergency in an effort to quell the incipient revolt, a move which had little impact. Road blockades, closures of airports and street demonstrations have caused large-scale economic disruption estimated to have cost up to 50–60 million dollars a day.

It is no coincidence that the protests have been concentrated in the South, in provinces plagued by some of the worst rates of poverty in Peru. These were also bastions of support for Castillo and the Peru Libre party in last year’s presidential elections. In Apurimac, Ayacucho and Cusco, Castillo took over 80% of the vote. Puno, the poorest region in Peru (only 40% of inhabitants have access to basic services like water, light and plumbing) has now become the epicentre of the struggle. Here, Castillo also won big amongst a majority indigenous population of Quechua and Aymara peoples — those bearing the brunt of all the horrors of Peruvian capitalism, and those feeling they had the most to gain from Castillo’s electoral promises to take on the ruling elite.

While some now call for Castillo’s reinstatement as president, this should not be taken as blanket support for his program and record. Indeed, the most radical layers to the forefront of the struggle are not without serious criticisms of Castillo, deeply aware that he committed fatal errors that laid the basis for the crisis of his government which was seized upon by the reactionary coup-plotters.

Escalating Movement Faces Down Brutal State Repression

After a pause in the struggle over the Christmas period protests re-emerged in the new year. The Asamblea Macroregional Sur, a newly formed regional assembly of workers’ and campesino unions, called an indefinite strike to begin on January 4. Despite increased pressure, Boularte has doubled down on remaining in power, stating: “I will not resign, my commitment is to Peru and not to a tiny group who are making the nation bleed.

However, it is painfully clear that it is the coup government and Peruvian state who are making the nation bleed. After one month of protests the death toll stands at 50, the vast majority at the hands of Peruvian state forces. Two massacres have been carried out; the first on December 15 in Ayacucho, where the Peruvian army murdered 10 protestors; the second on January 9 in the city of Juliaca, Puno where police killed 17 people, the majority with live ammunition.

Shamefully, the coup government has attempted to justify the bloodshed with crude characterisations of protesters as terrorists, a classic tactic of the Peruvian right known as “terruqueo”, who regularly accuse socialists and trade unionists of being connected to disgraced Maoist guerilla group Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path).

Violent state repression in response to mass revolts has been a key feature internationally over the last period. From Nigeria to Chile, Iran to Colombia, the ruling class finds itself backed into a corner and increasingly reliant on brute force to maintain control. Yet this often serves as a whip of counter-revolution, having the unintended effect of further radicalising the movement.

And this is precisely what has taken place in Peru: despite an imposed 3 day curfew a mass demonstration gathered in the town square of Juliaca for the burial of those murdered days earlier, the number of blockades has continued to grow, and the Workers’ General Confederation of Peru (CGTP) have been forced to play a more active role, calling demonstrations and assemblies in Lima.

Rotten Coup Government

Boularte was Castillo’s vice-president and ran on the same ticket with Peru Libre, although she was always seen as a safer pair of hands for Peruvian capitalism. The new government is now made up of technocrats and the right-wing Fujimoristas she campaigned against in the polarised 2021 elections. Predictably, the bosses’ organisation, Confiep, were quick to offer their endorsement of the coup government, breathing a sigh of relief that their political representatives had retaken the reins.

To get an insight into the utter rot of those members of the Peruvian oligarchy that make up the new government we need look no further than congressman Jorge Alberto Morante Figari of Keiko Fujimori’s Fuerza Popular (Popular Force). Not letting a good crisis go to waste, he took advantage of the political chaos to pass legislation that would remove protection of uncontacted indigenous people in the Amazon, a boon to big business eager to remove any barriers to exploitation of people and the planet.

On Tuesday January 10 the new government won a vote of confidence by a significant margin 73 in favour and 42 against, an apparent show of strength. Yet this parliament, dominated by right wing and establishment parties, is not an accurate reflection of the real balance of class forces. In fact, the vicious response of the Boularte regime indicates weakness and deep instability. Feeling pressure from below, 3 ministers have recently resigned, citing opposition to the crackdown on protests and a poll on Sunday January 15 showed the Congress had a disapproval rating of 88 per cent.

Political Disorder Symptom of Crisis-Ridden System

The current crisis in Peru is the latest in a series of political dramas that have engulfed the Andean country in recent history. Boularte is the sixth president in four years, and the tenth since 2000, with the majority of her predecessors’ terms ending in scandal, impeachments and, in the case of Alan Garcia, suicide.

In November 2020, the illegitimate impeachment of then president Martin Vizcara triggered a wave of protests that took aim at the entire political system and corrupt elite. They were also fuelled by mass anger at grinding poverty that was exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic (Peru had the highest death rate in the world). The demand for a Constituent Assembly to draw up a new constitution became enormously popular amongst workers and the poor masses as a way out of the political, social and economic crisis.

Frederich Engels explained how constitutions, far from timeless ideals, are products of the class struggle “established by victorious classes after hard won battles.” Peru’s 1993 constitution was drawn up under the Fujimori dictatorship, a regime which implemented brutal neoliberal economic policies coupled with murderous repression and a reactionary social agenda, representing a historic defeat for the working class and oppressed. As such, it both reflects and inscribes the rule of the loathed Peruvian oligarchy. Castillo made the calling of a Constituent Assembly a central demand in his 2021 presidential campaign.

Castillo’s Rise to Power

A rural teacher and trade unionist who seemingly came from nowhere, Castillo ran with Peru Libre, a self-described Marxist party led by Vladmir Cerrón. He promised to nationalise mines and impose taxes on the rich in order to fight rampant poverty and inequality. “No more poor people in a rich country” was the primary slogan of a campaign that tapped into the discontent of the Peruvian masses and their seething rage towards a corrupt oligarchy widely recognised as servile accomplices of the multinationals who plunder Peru’s vast natural resources.

Castillo narrowly beat right-wing Keiko Fujimori (by a mere 45,000 votes), the daughter of dictator Alberto Fujimori. The latter was backed by the bourgeoisie who mobilised all forces at their disposal into a rabid anti-communist and racist campaign. Notwithstanding Castillo’s weaknesses, such as his poor positions on women’s and LGBTQ+ rights and his willingness to make concessions on his program, his triumph was a massive victory for the working class and oppressed. It was therefore clear that, from day one, the ruling class would pull out all the stops to undermine and sabotage any left-wing political project.

As ISA warned at the time, the current period of global capitalist crisis, which finds concentrated expression in Latin America, made Castillo’s room for manoeuvre increasingly narrow. Carrying through the key aspects of his limited reformist program, like nationalisation of the mining sector, a redistribution of wealth and an agrarian reform, would meet the bitter resistance of the Peruvian capitalists and could only be achieved through continued mobilisation of the working class, poor and indigenous people.

Castillo’s Weakness Invites Aggression

But rather than waging an open battle against the corrupt ruling elite that he chastised during his election campaign, Castillo took the path of class conciliation. Bowing to pressure, he immediately watered down the more radical aspects of his program in order to calm the fears of the capitalists who were terrified by the threat posed by the workers, poor and indigenous people that were boosted by Castillo’s victory.

Yet Castillo’s efforts to appease the ruling class did not pay off. Prior to December 7, he had survived two impeachment attempts and came under investigation for claims of corruption and involvement in a ‘criminal network’ in the Peruvian government. These political manoeuvers were desperate measures of the bourgeoisie to remove a leftist president

Unfortunately, Castillo responded to these attacks by making further concessions, dismissing then prime minister Guido Bellido alongside other ministers regarded as more radical in order to bring in more moderate figures. In a mere 17 months there has been no less than 5 cabinets and close to 80 ministers.

Such an approach only alienated those who voted for Castillo, eager to deal a blow against the oligarchy, but became disappointed by unfulfilled promises of radical transformation. Feeling pressure from below last June, Peru Libre forced the resignation of Castillo, accusing him of implementing a “losing neoliberal program.”

Although Peru Libre expelled Boularte over a year ago for publicly disagreeing with the party, there is a real question of why she was a member in the first place and given such a high profile. This points to a deeper weakness of the leadership of Peru Libre. Instead of building a mass party of the working class and oppressed, democratically run by its membership, they opted for a policy of building alliances with pro-capitalist forces, a grave mistake that has led to the situation today.

Which Way Forward

There can be a genuine sentiment that Castillo was doomed from the beginning. Did he ever really stand a chance going toe to toe with imperialism, the Peruvian ruling class and their corrupt political system? While we in no way underestimate the ruthlessness of the Peruvian oligarchy, there is nothing inevitable about the current situation. Had Castillo mobilised the oppressed masses that brought him to power and used his position to deepen working-class and grassroots organisation, he would be in a far stronger position today.

Those on the streets are drawing radical conclusions and the last 17 months has undoubtedly brought tough lessons about the limitations of reformism. Now, the Peruvian masses must rely on their own strength and continue to build local committees of struggle to unite workers, campesinos and indigenous people and allow them to democratically discuss and coordinate the next steps of the movement, including self-defence.

These should be linked up on a regional basis, following the example of the Asamblea Macroregional Sur, and ultimately connected to a national assembly of elected delegates from across the country, with a concerted effort to deepen and extend the strike movement beyond the South. With the full power of the working masses properly harnessed, the immediate democratic demands for the resignation of Boularte, the release of Castillo, the calling of new elections could all be quickly won.

Should the ruling class feel they have no other choice, even the popular demand for a Constituent Assembly could be granted. However, lessons should be learned from neighbouring Chile, where the bourgeoisie did all they could to turn this process into a farce, ensuring it remained within safe institutional channels as well as leaving in place the sanctity of capitalist property relations. ISA, on the other hand, is in favour of a Revolutionary Constituent Assembly to be made up of delegates from the trade unions, peasant and indigenous organisations, as well as representatives from the student, feminist and LGBTQ+ movements, directly elected by the organs of popular power we see forming today, and subject to immediate recall.

In other words, a Constituent Assembly in which the working class and oppressed are in control and can chart a way out of the crisis through tackling the systemic roots of the endemic poverty, oppression and corruption which lie in capitalism and imperialism.

That would mean going beyond Castillo’s initial limited program, taking the mining, manufacturing, transport and banking sectors out of the hands of the multinationals and Peruvian capitalists, placing them under democratic workers’ control and management; a genuine agrarian reform that seizes the land from the mega-landlords and redistributes it amongst campesinos and indigenous people; and extending the rights of women and LGBTQ+ people.