This article was first published in 2008, but is even more relevant today with a Trump presidency, Black Lives Matter and rising struggles across the US.

This article was first published in 2008, but is even more relevant today with a Trump presidency, Black Lives Matter and rising struggles across the US.

This year marks the 40th anniversary of the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., who was killed on April 4, 1968 while supporting striking Memphis sanitation workers.

Unfortunately, the official commemorations of King often provide us with a sanitized version of his life and legacy and the history of the civil rights movement. It is now routine to hear right-wing politicians quote King to justify attacks on affirmative action or welfare, or to see his image in marketing campaigns by huge corporations like Apple.

Like so many fighters for the oppressed, the ruling class fears and opposes them while they are alive, but following their death an attempt is made to render their legacy harmless through distorting their actual ideas. During his lifetime King inspired millions with his vision that fundamental change in U.S. society was possible.

To J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI, which viciously harassed King and kept him under constant surveillance, he was the most dangerous Negro in America. The US establishment especially feared his growing radicalization in the last years of his life, when he spoke out sharply against the Vietnam War and began to question the capitalist system and even talk about democratic socialism.”

Strategy of Mass Struggle

King’s rise to prominence began with the Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1955-1956. The strategy of mass, nonviolent struggle against Jim Crow, first pursued by King in Montgomery, was in contrast to the traditional strategy pushed by the more moderate leadership of the NAACP. The NAACP focused on a legalistic strategy of court cases, fearing mass direct action would alienate their political allies in the Democratic and Republican parties.

Beginning especially in 1960, with the wave of sit-ins challenging segregation at lunch counters across the South, civil rights activists waged a series of heroic struggles aimed at winning desegregation and voting rights for blacks.

Their tactics were often criticized by liberal leaders, who urged them to rely on the government to enact change. King took up these attacks in his famous Letter from Birmingham Jail. He wrote, “We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed.””

King played a major role in organizing the mass struggle that shook Birmingham in 1963. Here, thousands marched to demand an end to segregation in defiance of court injunctions forbidding any protests. They faced down police dogs and fire hoses, enduring brutal beatings and numerous bombings and death threats. 2,500 ended up in jail at one point, including elementary school children as young as 6, but their tremendous courage brought widespread sympathy.

Only the fear of the example of Birmingham spreading to other cities, as well as the growing mood of impatience swelling among blacks in the North, convinced the Democratic administration of John F. Kennedy that some federal civil rights legislation would have to be enacted. They were also concerned that the negative publicity generated by the racist attacks in Birmingham would allow the Soviet Union to undermine the US grip in Africa and the rest of the Third World, where colonial revolutions were erupting.

This is in stark contrast to the widespread mythology crediting the Democratic Party for civil rights. The reality is that it was only under intense pressure from below and a growing radicalization among blacks that the federal government was forced to act.

Far from leading the struggle for civil rights, the Democratic Party under President Kennedy repeatedly ignored calls for federal intervention to protect civil rights activists. Kennedy attempted to downplay the civil rights issue in order to maintain the allegiance of the racist Democrats who ran the entire South the same Democrats who were unleashing police dogs on civil rights protestors. While King retained hopes in Kennedy and sought to cultivate a working relationship with his administration, he also grew frustrated with its inaction.

The experience of the civil rights movement shows that the key to change is not relying on the capitalist political establishment but rather building mass movements from below.

Opposition to the Vietnam War

King also came into serious conflict with the establishment over the Vietnam War. By 1965, King had turned against the war, and he increasingly saw the issues faced by blacks in the U.S. as linked to U.S. foreign policy. The Democratic Party, who started the war and prosecuted it under the Kennedy and Johnson administrations, exerted enormous pressure on him to remain a single-issue reformer and not to speak out against the war. Under this pressure, King hesitated to come out publicly.

King was coming up against the limitations of his reformist outlook and alliance with the Democratic Party. The strategy of the civil rights leadership, including King, was based on maintaining an alliance with the Democratic Party.

To come out against the war would mean a huge collision with the Democrats. As National Urban League president Whitney Young said, “Johnson needs a consensus. If we are not with him on Vietnam, then he is not going to be with us on civil rights.””

However, this strategy was at odds with reality. The Democratic Party was (and is) a cynical party of big business who were incapable of taking serious measures to eradicate racism since that would clash with the interests of US capitalism. The Vietnam War was completely against the interests of ordinary blacks, who were doing a disproportionate amount of the fighting and dying in a racist war to maintain colonial oppression.

Funding for the war was severely undermining the budget for the War on Poverty and social services relied on by blacks (as well as poor and working class whites). Politically, it was increasingly untenable to stay quiet on Vietnam. Blacks were increasingly rebelling against the war. King and other civil rights leaders’ silence was discrediting them in the black community.

Far from being a more realistic strategy, this reformist approach forced the civil rights leadership to compromise the interests of the oppressed. Instead of a socialist or fighting strategy, which starts from the needs of the oppressed and building the largest and most conscious movement to bring maximum pressure on the ruling class to concede to our demands, they were forced to limit themselves to what was acceptable to the political establishment.

King’s genuine commitment to the plight of poor and working class blacks eventually forced him to break with the logic of his previous position and come out sharply and publicly against the war in February 1967. Calling the US government “the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today,” King became the most prominent American to demand withdrawal from Vietnam.

As soon as King stepped outside of his issue to draw the links between U.S. imperialism overseas and the treatment of blacks within the US, the corporate media got in line to trash him.

The Washington Post warned him that he had diminished his usefulness to his cause, to his country, and to his people. Johnson referred to him as “that goddamned nigger preacher” and told King that his statements on the war had the same effect on [him] as if he had discovered that King had raped his daughter (Michael Eric Dyson, I May Not Get There With You: The True Martin Luther King, Jr., p. 61).

While Democratic politicians will attempt to claim the mantle of King’s legacy in the 2008 elections, his experiences were leading him away from the Democratic Party and toward more radical strategies. He even actively considered calls to run for president as an independent in the 1968 election on an anti-war, anti-poverty, civil rights platform, though in the end he unfortunately stepped back from doing so.

Tackling Poverty

In his last years, King increasingly turned his attention to problems of economic injustice and inequality. He saw that the victories won through the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 had done little to penetrate the lower depths of Negro deprivation and that the gains of the movement were limited mainly to the Negro middle class.”

Especially important in this process were his experiences in Northern ghettoes where the problems of working class and poor black people could not be laid at the feet of official legal discrimination. These conditions had fueled the riots in major cities during the mid-1960s and the growing militancy among a section of the black community.

In his search for a way to win real equality for African Americans, King began to draw the conclusion that a serious battle against poverty and oppression was necessary. Against separatist trends who wrote off all whites, King correctly argued for building a multiracial movement with poor and working class whites.

Speaking before a meeting of shop stewards in Teamsters Local 815 in 1967, he said, “Negroes are not the only poor in the nation. There are nearly twice as many white poor as Negro, and therefore the struggle against poverty is not involved solely with color or racial discrimination but with elementary economic justice.”

In 1968 King launched the Poor People’s Campaign. He hoped to go around the country assembling a multiracial army of the poor to march on Washington to abolish poverty in the U.S. and internationally and demand that the money being spent on the Vietnam War be redirected to provide jobs and income for the poor.

He aimed for more than just a symbolic march, planning a campaign of mass civil disobedience, including blocking traffic and staging sit-ins in Congress, to shut down Washington, D.C. King felt, “There must be more than a statement to the larger society, there must be a force that interrupts its functioning at some key point. To dislocate the functioning of a city without destroying it can be more effective than a riot. It is a device of social action that is more difficult for a government to quell by superior force. It is militant and defiant, not destructive.”

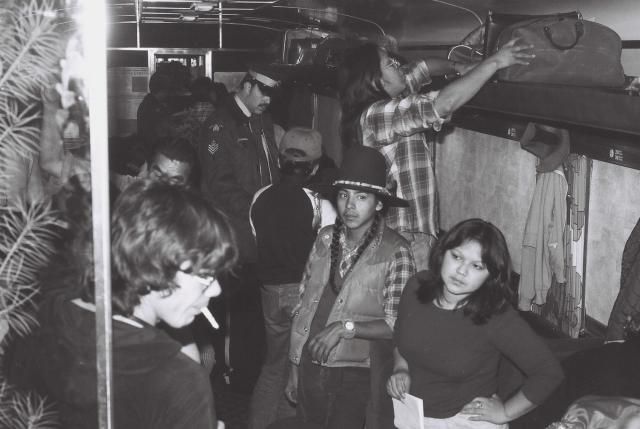

King hoped that the strike by 1,300 Memphis sanitation workers would be the kickoff for the Poor People’s Campaign. Tragically, he was gunned down before he could see the campaign through.

The State of the Dream

While memorials and celebrations of Martin Luther King often emphasize the civil rights era victories against Jim Crow, they could just as easily highlight the continuation of the most basic injustices in U.S. society. Official Census figures state that in 2006 24.3% of U.S. blacks lived in poverty vs. 8.2% of whites.

The situation that developed in Jena, Louisiana in 2007 where black teenagers were persecuted for standing up against a racist climate, including a “whites-only” tree at the local high school and the hanging of nooses, brought back memories of Jim Crow for millions of African Americans.

The struggles of the Civil Rights era did lead to important reforms but they did not culminate in fundamental economic change. The wealth of society was left in the same hands and in subsequent decades, African Americans have remained one of the most disadvantaged sections of the working class. All this underlines that the continuation of capitalism means a majority of blacks will continue to face nightmarish conditions.

This year we will hear many calls to honor King’s memory. We need to reclaim his legacy from the corporate media and politicians who attempt to use him to justify their system. Despite King’s political limitations, he was a genuine, determined fighter who inspired millions to struggle.

As he said in a speech exactly one year before his death, “Our only hope today lies in our ability to recapture the revolutionary spirit and go out into a sometimes hostile world declaring eternal hostility to poverty, racism, and militarism. With this powerful commitment we shall boldly challenge the status quo.” (When Silence Is Betrayal, April 4, 1967).

The real way to honor King’s legacy is to devote ourselves to an all-out struggle to eradicate racism, poverty, war, and all forms of oppression. As King was beginning to see towards the end of his life, this means a building a movement to abolish capitalism.

——————————————————-

Maybe America must move toward a democratic socialism”

Towards the end of his life, King was drawing far-reaching conclusions based on his experiences. He was increasingly considering the idea that a just division of society’s resources would have to mean breaking with the rules of capitalism, which relies on the poverty of black (and Latino) workers as an important source of super-profits due to their cheaper and more exploitable labor.

As he told journalist David Halberstam in early 1968, “For years I labored with the idea of reforming the existing institutions of society, a little change here, a little change there. Now I feel quite differently. I think you’ve got to have a reconstruction of the entire society, a revolution of values.”

King also began to talk about the need for socialism. In a speech delivered to his staff in 1966, he said, “You can’t talk about solving the economic problem of the Negro without talking about billions of dollars. You can’t talk about ending the slums without first saying profit must be taken out of slums. You’re really tampering and getting on dangerous ground because you are messing with folk then. You are messing with captains of industry. Now this means that we are treading in difficult water, because it really means that we are saying that something is wrong… with capitalism. There must be a better distribution of wealth and maybe America must move toward a democratic socialism.”

——————————————————-

BOX: Who Killed King?

King was clearly aware of the risks he was running by directly opposing the war and threatening to build a class-based movement independent of the two parties. Given his immense authority as the most prominent figure in the civil rights movement, King’s radicalization represented a huge threat to the U.S. ruling class.

They feared his increasing outspokenness on class issues, including a developing understanding of the power of the working class, as well as his growing openness to challenging the Democratic Party. He was definitely getting on dangerous ground. Like Malcolm X, the Black Panthers, and many other activists in the civil rights movement, King was being closely monitored by agents of the federal government.

King was shot and killed on April 4, 1968 as he stepped outside of his Memphis hotel room. Two months after the killing small-time thief James Earl Ray was arrested and convicted of the assassination. He was supposed to have acted alone and killed King out of racist motives. Many, including Martin Luther King’s son and late wife, do not buy this version.

In 1999, a Memphis jury ruled against the official government version in a civil suit brought by the King family. In his book An Act of State: The Execution of Martin Luther King, William Pepper, the lawyer who represented both Ray and the King family, presents powerful evidence that the U.S. government was heavily involved in a conspiracy to kill King.

————————————————

Quotes from King:

“I am convinced that if we are to get on the right side of the world revolution, we as a nation must undergo a radical revolution of values. We must rapidly begin the shift from a ‘thing-oriented’ society to a ‘person-oriented’ society. When machines and computers, profit motives and property rights are considered more important than people, the giant triplets of racism, materialism, and militarism are incapable of being conquered.” When Silence Is Betrayal, Riverside Church, April 4, 1967

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” Letter from Birmingham Jail, April 16, 1963

“The coalition that can have the greatest impact in the struggle for human dignity here in America is that of the Negro and the forces of labor, because their fortunes are so closely intertwined.” Letter to Amalgamated Laundry Workers, January 1962

“So often we overlook the work and the significance of those who are not in professional jobs, of those who are not in the so-called big jobs. But let me say to you tonight that whenever you are engaged in work that serves humanity and is for the building of humanity, it has dignity and it has worth.” AFSCME Memphis Sanitation Strike, April 3, 1968