Vlad B is a member of CWI in Romania.

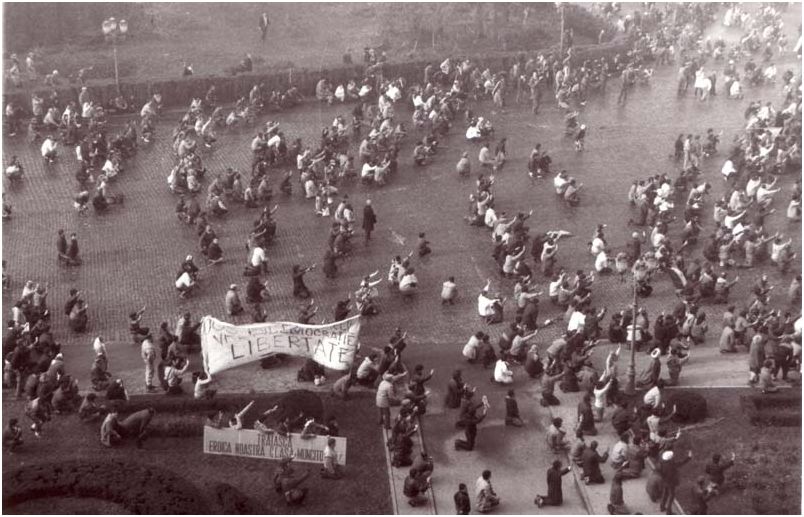

30 years ago, people took to the streets against the Stalinist regime of Ceausescu, having put up with years of harsh austerity, bureaucratic control of society and lack of liberties. Nicolae and Elena Ceausescu were put on trial, found guilty of genocide and executed all on the same day 25th December 1989. However, the uprising driven from below mainly by workers and youth was not followed by the freedom and prosperity people were hoping for.

Capitalist restoration, which followed the December 1989 uprising, led to the large scale collapse of industry and agriculture, forcing millions to emigrate. The majority of those who have remained are confronted with poverty, low wages, job insecurity, precarious public services and a political caste that is solely in the service of capitalist elites.

After 30 years of neoliberal policies, living standards in Romania are very far away from the shiny promises of the “free market” ideology of the 1990s. Today, around a third of the population is at risk of poverty, while 20% of the active workforce live under the poverty threshold. Around 40% of those working in the private sector are on the minimum wage, which – despite its successive increases over the last few years – is only €446 per month, more than €100 less than the living wage. That comes along with a drop in the number of secure jobs after 1990 from 12 to 6 million.

Meanwhile, the ruling class is made up of, on the one hand, oligarchs and bureaucratic networks which often emerged from the ruins of the former Stalinist nomenclature and, on the other, a comprador elite that defends the interests of foreign capital. The state institutions and main political parties serve the different factions of this ruling class. Romania is, therefore, a highly polarised society, the third most unequal in the entire EU after Bulgaria and Lithuania, with extreme levels of wealth and poverty more typical for a neo-colonial country. Between these extremes lies a fragile middle class, concentrated in a few urban centres like Bucharest, Cluj and Timisoara.

Many Romanians believe this dire state of affairs is not as much a result of capitalism per se but of the “wrong” kind of capitalism applied in Romania. They believe that an otherwise fair and efficient system has been perverted by indigenous corruption and clientelism. This is an illusion. Wherever capitalism has provided prosperity and rights to ordinary people, it did so despite itself, under the pressure from below of people organising and fighting against bosses and their political cronies. The absence or weakness of such collective bottom-up pressure allows capitalism to continue with its unhindered exploitation and oppression, in which decent wages, dignified working places or public investments are hurdles that are to be avoided. This is precisely what has happened in Romania since 1989, where the political left and the labour movement have been too weak to pose any effective resistance. In other words, Romanian capitalism is, in fact, a very authentic form of capitalism, as the maximisation of profits is less hampered here than in most European countries.

Colonial status and corruption

The maximisation of profits mostly benefits foreign companies, particularly from Germany, Austria, France, Netherlands and the US. Not only do they pay very low wages to a largely well-qualified workforce, but there is also one of the lowest, flat-rate corporate taxes in the EU – 16%. On top of that, they often under-declare their real profits – a form of structural corruption that the mainstream anti-corruption discourse, often weaponised by one faction of the ruling class against the other, has conveniently ignored.

Thus, Romania is also a good illustration of another key feature of capitalism: the subordination of developing countries to developed countries. No less than 85% of the Top 100 companies in Romania are multinational, who have a crushing domination over most key sectors of the economy, including energy, commerce, banking, heavy industry, auto industry, food industry etc. In 33 of the 41 counties of the country, the most successful company is one controlled by foreign investors.

For Western European ruling classes, Romania is not a poor relative, who they want to help catch up, as naïve pro-Europeanism claims, but on the contrary. Even the National Bank of Romania, which usually dutifully obeys the directives of the IMF and the EU institutions, declared last year that big foreign banks deliberately keep Romania in a state of financial underdevelopment, refusing to provide sufficient credit to local businesses. It is further proof of the country’s subordinate place in the international economic system. Because in a system based on unscrupulous competition, the stronger countries will always try to take advantage of the weaker ones and thereby cap their development or guide it to suit their own interests. The relatively successful cases of underdeveloped countries that have managed to partly, and unevenly, catch up with the West have done so through heavy state intervention in the economy, although they themselves are not immune to the inequalities and contradictions of capitalism.

However, in the case of Romania, the state does not even attempt to interfere in any significant way with the dominance of foreign capital, despite some demagogical statements from the recently ousted government led by the Social Democratic Party (PSD). In fact, between 2016 and 2019, PSD implemented further measures in the service of the rich and the bosses, including the reduction in the flat income tax to 10%, the transfer of social contributions from the employer to the employee, and the withdrawal of unemployment benefit from people refusing the first job coming their way. The new openly neoliberal government of the National Liberal Party (PNL) – backed by a parliamentary coalition of right-wing forces opposed to PSD – is keen to push the pedal even deeper in defence of profit, including a potential cut of the minimum wage.

Of course, such policies benefit not only foreign companies but domestic capitalists and oligarchs too, who are no less ruthless in exploiting their workforce. Indeed, the illusion that we should oppose the dominance of foreign capital by aiding national capital needs to be firmly rejected. Just because they are Romanian doesn’t make capitalists any better friends of workers’ rights and interests. The struggle between capital and labour remains paramount in today’s society, and Romanian workers need to challenge their bosses regardless of their nationality.

Some of these oligarchs have often taken political power in their own hands, such as the former PSD leader Dragnea, now in prison for corruption. It is by understanding this that we can make sense of the burning problem of corruption. It is not some kind of cultural or national disease, but an essential part of capitalism – a vehicle for primitive accumulation of capital by an incipient, post-1989 capitalist class that has had to both compete with, and parasite on, a much stronger foreign capital, both economically and politically, backed by EU treaties and directives shaped according to their interests. In other words, corruption is meant to make up for the deficit of capital and market access that the new Romanian bourgeoisie (or any other emerging national bourgeoisie in the history of capitalism) had to start with – like a football team that starts the game with a 5-goal handicap and has to cheat in order to make up for it, and still fails to equalise.

Popular disillusionment

The inevitable effect of these post-1989 realities has been increasing political disenfranchisement. The fact that turnout in parliamentary elections has never been above 50% since 2004 sums it up. All the main parties, old and new, despite numerous reconfigurations and realignments, have consistently proven that they only represent the elites, from home and abroad. Given the lack of a genuine left alternative, PSD continues to be the most popular party in the country, the only one to offer some minimal social concessions. Its rivals, PNL in particular, are stuck in a dogmatic neoliberal agenda that glorifies foreign investment, deregulation, low public spending, and privatisations.

As illustrated above, PSD itself is very much supportive of such policies, which is coupled with an increasingly salient social conservatism, as shown by its endorsement of the anti-same sex marriage referendum in 2018. This places the party in the same ideological camp as Law and Justice from Poland or Fidesz from Hungary. Therefore, despite what some liberal commentators might claim, for the last few years Romania has been part of the broad regional trend of right-wing populism, which mixes weak social concessions with a demagogical appeal to “traditional values” and “nationhood” in order to capitalise on the disillusionment that many have with the Western, neoliberal model of democracy.

But neither these right-wing populists, nor the defenders of the pro-Western, neoliberal model have any viable solutions to the real problems of Romanian society. Neither wage-led growth, nor extreme measures to facilitate foreign investments (i.e. profits) can bring the country out of its structural underdevelopment and economic subordination. More and more people are becoming aware of the incapacity of capitalism and its political representatives to solve the question of low wages, of insecure employment, of inadequate public services, of unaffordable housing, of an economy that is over-dependant on foreign industries, of the destruction of the environment, of the oppression of women and other groups. In contrast to the first two decades of capitalist restoration, over the last ten years we have witnessed, especially among industrial workers and the youth, a growing rejection of the previously undisputed ideology of the free market.

In search of an alternative

These shifts in consciousness started with the 2007-2008 crisis and the austerity measures that followed it, both at home and abroad. These laid the basis, in the last decade, for the emergence of a Romanian independent left, initially gathered around editorial projects such as “CriticAtac” or the “Gazette of Political Art”, which hosted some of the first anti-capitalist discourses in post-1989 Romania. They in turn helped to develop activist groups which participated in campaigning on key issues such as housing, like the Common Front for the Right to Housing and Social Houses Now.

More recently, we have also witnessed the relative rejuvenation or creation of explicitly left-wing political organisations, such as the Socialist Romanian Party (PSR) and Demos respectively. While this confirms the shift in consciousness among some layers in society, both organisations display obvious ideological limitations: neo-Stalinist in one case, social democratic in the other. Despite recently attracting some new young activists, PSR continues to be characterised by nostalgia for the Ceausescu regime – one of the worst expressions of bureaucratic rule in Central and Eastern Europe, whose late economic policies amounted to a brutal austerity that the IMF itself praised at the time. PSR combines this with a call for “a socialist market economy”, using the contemporary capitalist and imperialist China as a model to follow, as well as completely disregarding the question of women’s rights or the discrimination of the Roma.

On the other side, Demos believes in a capitalism with “a human face” resembling that of post-WWII Keynesian social democracy. However, the kind of reforms that this would entail are simply not attainable in the context of a deep systemic crisis of capitalism that leaves very little room for concessions, even less so in the case of a weak state such as Romania, subordinated to foreign capital and to the European institutional framework. The leadership of Demos fails to see that and instead endorses the kind of naïve Europeanism that resembles that of the British Liberal Democrats.

Hence, a realistic left alternative is, in fact, a radical, socialist alternative that skillfully poses the question of replacing a system based on profit with one based on needs – even more necessary now with the environmental catastrophe looming ever more dangerously. But the kind of socialism that Mana de Lucru (CWI sympathisers in Romania) fights for is qualitatively different from the degenerated, bureaucratic system that existed before 1989. An economy aiming to fulfill the needs of all people and communities cannot work unless you ask people and communities what their needs are! Democracy is, therefore, indispensable to socialism, which otherwise is destined to be yet again captured and distorted by a new privileged caste.

At the same time, socialists cannot afford to be sectarian. Mana de Lucru is open towards principled cooperation with other genuine left forces that aim to orient themselves towards the mass of workers and youth. Thus, we call on the other left groups and the trade unions to build a structured form of discussion and collaboration that would allow us to attract new layers of workers and youth coming into struggle. This could provide the basis for the creation of a new mass workers party that would represent the interests of our class, that would fight in the workplaces, on the streets and in the institutions for better wages, dignified jobs, quality public services, affordable housing for all and, in general, for an economy under democratic control that serves the people and the environment, and not the other way round.

There is more potential for establishing a political alternative in Romania than at any time in the last 30 years of capitalism. In 2019, we witnessed the most significant wave of strikes in decades. Industrial disputes such as that at Astra in Arad, where Romanian and Indian workers joined forces to ask for better wages for all, or the one at Electroaparataj in Targoviste, which lasted for over 3 months, show what huge potential there is. The Romanian working class’ appetite for struggle has increased visibly, and the political left together with the trade union movement need to channel it towards building the only genuine alternative to the status quo – a fighting, mass working class party that can propose a democratic and socialist alternative.