Russia in February 1917 was a mass of tensions and contradictions. The slaughter of war seemed endless, the countryside remained gripped by feudal backwardness, the workers in the cities were hungry and angry and millions of national minorities were locked in the oppression of the empire.

Russia in February 1917 was a mass of tensions and contradictions. The slaughter of war seemed endless, the countryside remained gripped by feudal backwardness, the workers in the cities were hungry and angry and millions of national minorities were locked in the oppression of the empire.

The soldiers were often sent to the front without rifles, bullets or even boots. As well as the battles, they suffered from disease, hunger and incompetent officers.

Russia was overwhelmingly rural, mostly serfs tied to the land. As there were few machines, most power for farming was muscles. Sometimes animals, but often humans, pulled the ploughs and harvested the crops. It was a backbreaking existence. With millions of men in the army, women and old men did most of the farming.

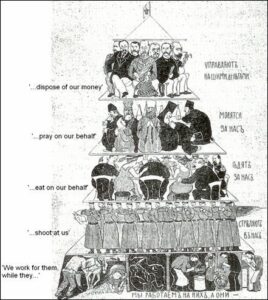

The Russian empire was ruled by a dictatorial feudal aristocracy headed by the Tsar. There were very limited human rights and only a superficial facade of democracy, with a weak and rigged parliament. Most Russians were illiterate. The empire still used the Julian calendar, replaced in most of Europe hundreds of years earlier.

Thrown into this overwhelming backward society there were large modern factories in some of the big cities. The contrast between the feudal countryside and the newest of industrial technology and production was immense. The working class in Russia, although a minority, was growing rapidly with militant traditions.

In 1905 the workers of Russia led an attempted revolution that included peasant uprisings, and mutinies in the army and navy. Although the revolution was bloodily repressed, with over 10,000 killed, the workers had gained valuable experience. They organized workers’ councils to coordinate the strikes. These grew to have mass support, 80,000 members in Moscow, and controlled much of daily life in the cities, deciding what would be done, ensuring food was supplied, hospitals had power, etc. In Russian, the word for council is Soviet.

On International Working Women’s Day 1917 (February 23 by the old calendar) the women workers of Petrograd went on strike. The next day, rather than return to work, more women and men joined, with 200,000 on the streets. The main slogans were End the War, Bread and Down with the Autocracy.

The troops in Petrograd refused to attack the strikers. Many mutinied, joining the demonstrators, challenging the police, who still supported the regime, and in some cases distributing rifles to the demonstrators.

The Cossacks, an elite force often used for repression, were mobilized onto the streets on horseback. However, while not mutinying, they allowed the revolution to continue.

“One of them gave the workers a good wink. This wink was not without meaning.… In spite of renewed efforts from the officers, the Cossacks, without openly breaking discipline, failed to force the crowd to disperse.… Officers lined the Cossacks across the street as a barrier to the demonstrators. But even this did not help: standing stock-still in perfect discipline, the Cossacks did not hinder the workers from “diving” under their horses. The revolution does not choose its paths: it made its first steps toward victory under the belly of a Cossack’s horse. A remarkable incident!”

– Trotsky, History of the Russian Revolution

The ruling class’s last line of defence of their power was crumbling, as the “armed bodies of men” (Engels) became thinking human beings. Control slipped from the hands of the old order. A week after the strikes began the Tsar abdicated.

Although the revolution was mostly limited to Petrograd, it rapidly spread across all of Russia. The early days of the revolution were liberating and exciting.

Two forces now held power. The Provisional Government: unelected and made up of self-appointed politicians from the old parliament, mostly liberals, conservatives and moderate socialists. The elected Petrograd Soviet represented the workers and soldiers.