Cormac Kelly is a member of Socialist Alternative, England, Wales and Scotland

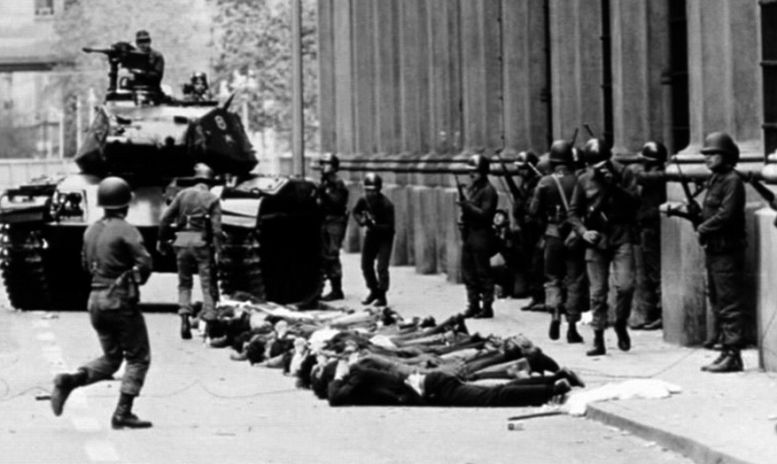

On 11 September 1973, fifty years ago, General Augusto Pinochet launched his brutal military coup, drowning in blood the revolutionary movement that had been inspired by the government of Salvador Allende.

For Marxists the study of history is not a passive diversion or academic activity, but is critical for understanding and learning lessons for the cause of working-class power in the socialist revolution. We analyse, discuss, and understand so that errors are not repeated, and tragedies are avoided.

The events of Chile leading up to 11 September 50 years ago, are a major indictment of the failure of leadership of the workers’ parties to assimilate the lessons of the past such as the Paris Commune and the Spanish Civil War, and avoid a potential revolution being drowned in cruelty and blood.

The Popular Front

The socialist Salvador Allende was elected president of Chile in 1970, with a broadly based coalition of Socialists, Communists, Radicals and so-called ‘progressive elements’ of the bourgeois in the Unidad Popular (UP) or Popular Front.

After repeated attempts in elections, he finally won in 1970 defeating the right-wing Christian Democrats. In doing so he raised enormous expectations amongst the country’s working class and peasantry. Now at last they could create a new society in which they could raise themselves out of poverty and gain real control of their lives.

Chile faced exploitation on a huge scale, in the form of foreign investment in mines and industry, paying the highest prices for equipment, licences and patents together with North American loans which stipulated that products and services were only bought in the US, and that goods be transported in American boats. Imperialism had taken away colossal profits, equivalent to twice the amount of capital invested in Chile throughout the whole of its history.

Failure of Chilean Capitalism

Chilean society had failed to develop into a modern state with reforms in agriculture sorely needed as landless peasants lived in poverty; 30% were smallholders with insufficient land to meet their own needs, let alone produce a surplus for the rest of the population and the big landowners dominated.

Leon Trotsky’s theory of the permanent revolution in neo-colonial countries in the epoch of imperialism explains this. Unlike many Latin American countries, Chile was formerly a democratic republic for some decades before 1970. But its bourgeois was weak, compromised and could not use their democracy to introduce land reform in particular. So Trotsky argued that as the proletariat challenges bourgeois property in its struggle for democratic rights “the democratic revolution grows over directly into the socialist’ revolution.”

For a socialist revolution in Chile to be successful it had to be part of a movement towards world revolution. An isolated workers’ state would find itself under remorseless attack from imperialism which would do everything to undermine and destroy it. Internationally there was enormous interest in what Allende was trying to do. A successful overthrow of capitalism in Chile would be the basis for an appeal for the working class of Latin America to overthrow their own national bourgeoisie and create a socialist federation. In turn this would inspire workers across the planet and act as an impetus to world revolution.

The capitalist class in Chile, arriving late onto the scene of history in an epoch of imperialism, had long ceased to play the kind of progressive role found in countries such as Britain and France in the 17th and 18th centuries, and in its fractious morbidity had neither the drive nor inclination to lead a bourgeois democratic revolution and national liberation. The interests of the big landowners, the bankers, and the capitalists, legitimised by the church, were fused together in a grotesque oligopoly which controlled, in league with imperialism, the economic life of the country. Capitalism did not subdue the semi-feudal landlords, preferring to form this unholy alliance.

In the 1950s, a “modern” bourgeois party the Christian Democrats was formed which used radical language to attract votes in the countryside but in power only slowly implemented agrarian reform. They demonstrated their weakness by surrendering to foreign imperialism and leaving the country’s copper and steel industries in the hands of US corporations.

Working class traditions

The only power capable of opposing this ruling clique was the working class. The Russian revolution of 1917 provoked enormous militancy amongst the Chilean workers whose unions and political parties increasingly played a key role in the class struggle and were even able to extract concessions.

Workers’ parties were formed but soon influenced by the ideas of the Popular Front which involved them going into coalition governments with the bourgeoisie. The Stalinist bureaucracy in Russia dominated the Comintern, (the organisation of world Communist Parties) and from the 1930s heavily promoted Popular Fronts which later Leon Trotsky was to describe as a “strike breaking conspiracy.”

The Chilean Socialist Party formed in the 1930s was a conscious attempt by the masses to create independent working-class policies. Under pressure from the Stalinists the leadership however entered a Popular front with the “progressive” Radicals, a bourgeoisie party, in 1938 arguing this would be the first step to socialism. After some reforms it quickly came into conflict with the workers’ movement and plunged into reaction.

History was to repeat itself again when Salvador Allende became president in 1970 of a Popular front. Allende argued that his UP government would move Chile from a largely backward state to an advanced social democracy, “capable of counteracting the effects of age-old exploitation” (UNCTAD conference April 1972). His intentions were honourable but also devastating as the military coup d’état of the 11 September 1973 was to prove.

So, what should be the attitude of revolutionaries to the Popular Front. Allende’s government gained huge support especially after reforms were enacted amongst the Chilean people. Patiently, we would call for the need to break with bourgeois forces to consolidate gains and point out the dangers of making concessions to the capitalists and the army. A united front of all working-class organisations and parties with clear transitional demands to break with capitalism and transform Chile was necessary.

Capitalist state

We can learn from Karl Marx who came to three significant conclusions after studying the defeat of workers in the Paris Commune of 1871. The working class simply cannot lay hold of the ready-made state machinery and wield it for its own purposes; they must destroy it. Secondly, the bourgeois of any country are capable of unthinkable levels of savagery and barbarism to repress and crush workers threatening their wealth and power. Finally, the working class must be ready to defend any gains made, if necessary, with audacity and force. Allende and his government believed that capitalism could be reformed out of existence by legislation. Because of this they did not confront the state, allowing the forces of reaction to build and failed to mobilise the working class.

Lenin implacably opposed the Russian bourgeoisie but for periods the Bolsheviks were a faction of the RSDLP and created united fronts until his party won the support of the majority of the working class. His book The State and Revolution, written in 1917, pointed out that the state exists not to reconcile opposing classes in society but is a symptom of “irreconcilable antagonisms” between the bourgeoisie and the working class. In history, it has acted as a force for the oppression of one class by another, upholding exploitative economic relationships in capitalism. It establishes a legal system that gives a false “legitimacy” to exploitation, while building up “armed bodies of men” such as the police and standing army to uphold the established order by force if necessary. Exploitation only ends when the proletariat seizes power, abolishes capitalism, and builds a workers’ state.

The living experience of Chile confirmed Marx and Lenin’s ideas and actions and refuted those of Allende. Feeling assured in the cosy myth that Chile was the England of South America, a country where military coups were allegedly never planned, the UP government appeased the army. By January 1971 members of the military were already nominated to positions in government such as in the newly nationalised copper industry. In an interview with the foreign press in May 1971, Allende explained that he wanted the armed forces “integrated directly with Chile’s process of development.”

Then he defended the military in glowing terms stating, “The great characteristic of the armed forces of Chile has been their obedience to the civil authority, their unquestioned regard for the public will as expressed in the ballots, for the laws of Chile and for the Chilean Constitution. It is my firm intention, as it is of Unidad Popular, that the armed forces will maintain their professional attitude.”

The UP had already made an agreement with the Christian Democrats not to interfere in the military in any way and no changes were to be made except with the approval of the Congress, the bourgeois parties having a majority. Workers would only participate in industry and not take it over. In Allende’s words, “We know that to change the capitalist system, while respecting legality, institutionality and political freedom, means that we must keep our activities in the economic, political and social spheres within certain limits.” (May 1971). Attempts at land occupations were discouraged on the grounds that the law was not being respected and it would provoke reaction.

Ruling class sabotage

The ruling class was not going to put up with any attempt to undermine their system which enabled it to make profits and keep workers in poverty and ignorance, without a brutal fight to the death. The high expectations of the working class put the UP government under pressure to carry out nationalisation which in turn represented a significant attack on the capitalist class with state ownership of copper, coal, iron, nitrate mines, the textile industry, and telecommunications. Popular support grew for the government with its policies of free milk for children, freezing of rent and prices, and wage and pension increases. The left won a majority in the April 1971 municipal elections; the Christian Democrat party fractured with some MPs going over to the left. Both the workers and most of the middle class supported the government.

With increasing concern, bordering on panic, the demoralised ruling class vacillated and then made plans to preserve their power and position. A revolutionary organisation such as International Socialist Alternative, providing leadership would have implemented a program and perspective to guard against the danger of reaction. Our program would have included peasant committees to take over the land, a decree on land nationalisation legitimising revolutionary facts on the ground; workers’ control of industry to prevent factory closures, with industry being nationalised; local action committees set up by trade unions to set prices and rents.

Allende immediately on assuming office dissolved the Mobile Guard, a notorious government force that had repressed workers, peasants, and students since 1960; but that did not stop reaction piling up new arms. So, a worker’s militia, based on the unions set up to defend workers gains was necessary. An appeal to the army rank and file, workers in uniform to set up soldiers’ committees should have been made. Elements of dual power sprung up with Chilean workers creating “cordones industrials” or workers assemblies (similar to the Soviets in the Russian revolution), which could have implemented the program outlined above eventually destroying the bourgeois state apparatus in socialist revolution.

Leadership failures

Instead, the Chilean ruling class were allowed to sabotage the economy and built opposition amongst small businesses such as private lorry drivers who blocked roads. Middle class support for the UP drained away. By June 1973 armed forces were disarming workers, searching for weapons in the workers districts and factories and acting against sailors affected by revolutionary propaganda. The El Tancazo uprising of the army against the government failed but sparked anger amongst workers who staged strikes, occupied factories, and marched on government buildings.

But there was no leadership and they were told to go home. A new coup was hatched. US imperialism cut off aid to Chile and tried to undermine the sale of copper from the country; the CIA played their poisonous games promoting anti-government propaganda and gathering intelligence. Incredibly Allende brought members of the military into the cabinet to appease the growing reaction including General Augusto Pinochet in the belief he would be loyal to the government.

On 4 September, seven days before the coup, huge demonstrations of workers in defence of their government were held. Over 500 factories were taken over by workers who gathered arms, set up militias and appealed to rank and file soldiers. One of the main demands on the demonstration was a call to Allende to arm the workers. He had set in motion processes he could not control with workers ready to fight and waiting for leadership. Instead of organising resistance he told demonstrators to go home. Loyal soldiers led by Pinochet then seized power; most of the army could not be trusted and were confined to barracks. The Chilean Road to Socialism became for the masses, the road to hell. All the gains of the previous years were lost, and activists faced a nightmare of arrests, imprisonment, and torture.

There is nothing worse for the working class to surrender without a fight. In Chile the best working-class militants had little opportunity to defend themselves. In the Paris Commune, the Asturian uprising, and the Civil War in Spain, workers fought, establishing a revolutionary tradition which a new generation built on.

Salvador Allende had considerable personal popularity and prestige throughout Chile. He did not flee like some making excuses but died in the army takeover and so is regarded by many with admiration as a hero. But he must take his share of responsibility for the coup. His lack of revolutionary leadership, in which he was supported by the Communist Party, resulted in his inability to mobilise the working class in their defence and the naive belief that compromising with capitalism was the way forward all led to catastrophic defeat. International Socialist Alternative believes the only way to pay real homage to the memory of Allende and the thousands who suffered and died is to learn from the experience in order not to repeat it.