Finally Canada’s New Democratic Party (NDP) has a new leader. Jagmeet Singh won 54% of the votes of party members on the first round. His 35,266 votes were almost three times more than those received by second placed Charlie Angus. He is presented as young, 38, and fashionable. Does this amount to a great new future for the NDP?

Before and after the election defeat of 2015 the majority of the NDP’s MPs and bureaucrats showed little desire for radical change. In contrast, the federal Liberals, led by Justin Trudeau, went from 36 MPs to 184 MPs as they read the mood of Canadian society for change and outflanked the NDP with a more radical image. The NDP slumped from the official opposition with 95 seats to the third party with 44 seats. Yet Mulcair wanted to stay on as leader and faced little resistance from the MPs. Only after a narrow defeat in the 2016 convention was there a leadership contest which took another year to complete.

Singh was member of the Ontario legislature rather than a member of the federal parliament. He resigned his Ontario seat after winning the leadership but, so far, he has shown no intention of running for Parliament before the next general election in 2019. While he started as an outsider, he quickly became the favoured candidate of the party’s leadership. He gained the support of 11 MPs, the most of any candidate.

A key part of leadership campaigns in the NDP is signing up new members rather than convincing the existing membership. The membership jumped to 124,000 during this leadership race, an increase of 83,000 members. Singh was by far the most successful, recruiting 47,000 new members, 57% of the total. He also led in fund raising, between May and September he raised 53% followed by Angus at 20%, Ashton 16% and Carron 11%.

Singh’s youth, media savvy and charisma, in contrast to Mulcair, appear to be the NDP’s answer to Justin Trudeau. He is popular among a section of young people. Singh is both the first member of a visible minority and from the Sikh faith to lead a major federal political party in Canada’s history. This is a truly historic moment in Canadian politics. But while one may celebrate this development, the key issue for the future is not his ethnicity but his politics.

In the leadership campaign, Niki Ashton was the most left-wing candidate. She talked about change and returning the NDP to its roots, criticizing the recent weak political campaigns of the party. While Ashton talked of tackling inequality she did not run a Bernie Sander’s style campaign. Her meetings were low key, with only a couple of hundred attending in Toronto or Vancouver. There were few sparks, little passion and hardly any working class presence. Charlie Angus also criticized the past NDP failures and called for a change of direction.

Singh identifies as a progressive but not as a radical or socialist. He was content sitting on the centre spot. Disappointingly, Singh did not show any indication of moving NDP towards its more reforming or socialist roots. There was a lack of criticism of the NDP’s past failures and unless a political party owns up to its past mistakes, it cannot expect to do anything different in the future. One got the same ‘positive politics’ vibe from Singh that has been associated with Justin Trudeau, but more important than abstract positive politics is political content. Singh’s choice of Guy Caron, the most right wing of the three defeated leadership candidates, as his parliamentary leader points the direction that the NDP is most likely will take in the future.

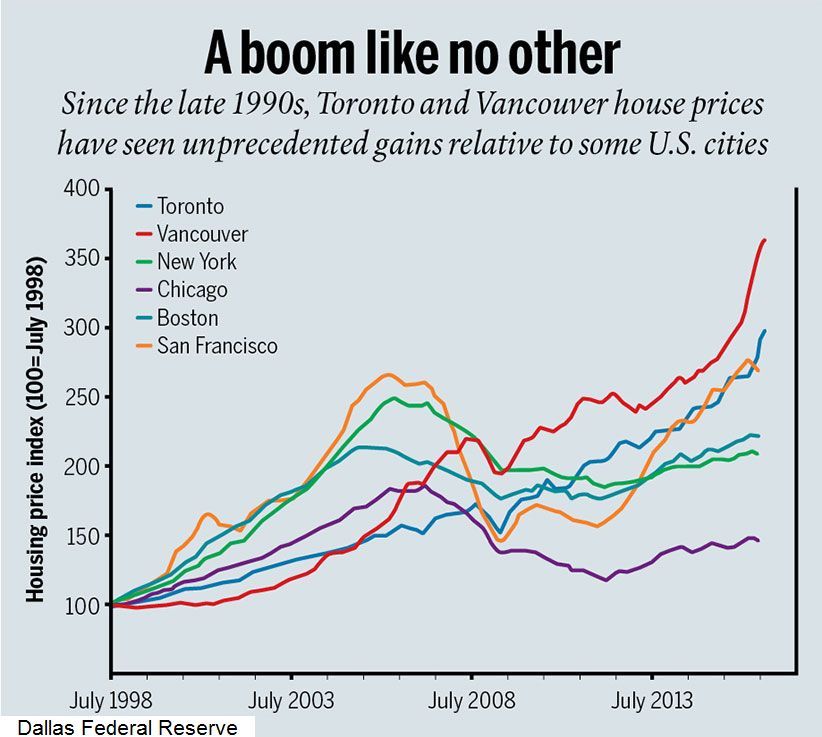

Politically Singh largely sat on the fence, taking a long time to speak out against the Kinder Morgan pipeline, or made vague statements such as tackling inequality, but without any concrete proposals for action. He promised to initiate electoral reforms, but again without clear indications of what that means. Shockingly, his position on the housing crisis is still unclear. Singh appears comfortable to continue to largely speak in platitudes – sounds good but weak on substance. His soft-left, at best, position has done more harm than good for not just the NDP, but for the Canadian working class.

Singh’s strong new membership numbers are pointed to as evidence of his ability to reach out to people as a popular leader and evoke interest in the NDP. However, when Mulcair ran for leadership in 2012 membership reached 128,000, only to see the numbers fall to around 40,000 in a few years. Will the new members Singh has signed up remain or will this happen again? Basing the election of the leader on new members weakens the influence of party members who actually do the work, and often reduces the election to a popularity contest.

The dumping of Mulcair along with discussion of the Leap manifesto at the NDP convention 18 months ago was seen by some as a shift to the left in the Party ranks. Hardly. The victory of Singh shows that the NDP members are not primarily concerned about the policy failures of the last election defeat or building a radical alternative. The priority seems to be choosing a perceived “winner”, another Jack Layton (someone who had consolidated the NDP’s steady rightward shift), someone to rival the youthful, charismatic Trudeau.

In a nutshell, the NDP appears to be in the same political dimension that it was in the past. Jagmeet Singh’s election may breathe fresh life into the party for a while, but when his honeymoon ends, his politics will reveal the same positions that resulted in the 2015 defeat. The working class, Indigenous people, the poor, students and the environment need a party that does much better than this. There is no indication that Jagmeet Singh will break away from the NDP status quo.

Notwithstanding Singh’s claimed popularity, the most popular politician in Canada is neither Trudeau or Singh. It’s not even a Canadian, but a 74 year old American by the name of Bernie Sanders. As an example, when in October, 2017, it was announced that Sanders was coming to speak in Toronto, tickets for the venue’s 1,700 person capacity were all snapped up in 2 minutes – 20,000 had tried to get a ticket.

Canadians are proud of their public health system, but the lack of a national pharmacare program is a major failing. Correcting this is official NDP policy, yet Mulcair never brought it up as an issue in the last election campaign. There seems no chance that in the next election we will see Singh barnstorming around the country a la Corbyn, Sanders or Mélenchon, stirring up people’s passions about the rip-offs of Big Pharma.

The NDP does not campaign day to day in communities and workplaces. This is not due to the temporary situation of being without a real leader in the time since Mulcair got his marching orders. The malaise is at the top, accompanied by the lack of a vibrant orgnization at the bottom has been the case for some time.

The NDP will need a radical transformation if it is to meet the needs of most Canadians. What is needed is a democratic party controlled by the membership, that campaigns year round in communities and workplaces, and supports struggles. The party needs a program to tackle the power of big business and the wealthy minority, redistribute wealth to raise wages and provide good public and social services, ends all forms of discrimination and create an economy with full employment and a healthy environment. Singh’s victory does not advance this change, it will take working class struggles.