The 1970 Earth Day provides us valuable lessons for the fight against climate change today, including how mass movements of ordinary people force change from below. The mass teach-ins—which involved millions from all sections of society—show the type of movement we need now.

The world is on fire and Trump and the billionaires are taking away the fire hydrants. He’s opened up so much federal land to drilling that even the oil CEOs are telling him to stop! Beyond that, he’s looking to gut the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and setting his sights on the Clean Air and Water Acts.

Before these protections, US were so polluted that, in 1969, the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland blew up in flames. One year later, the EPA was created and the Clean Air Act passed. This victory didn’t come as the result of any benevolent politicians—least of all the then-President Nixon.

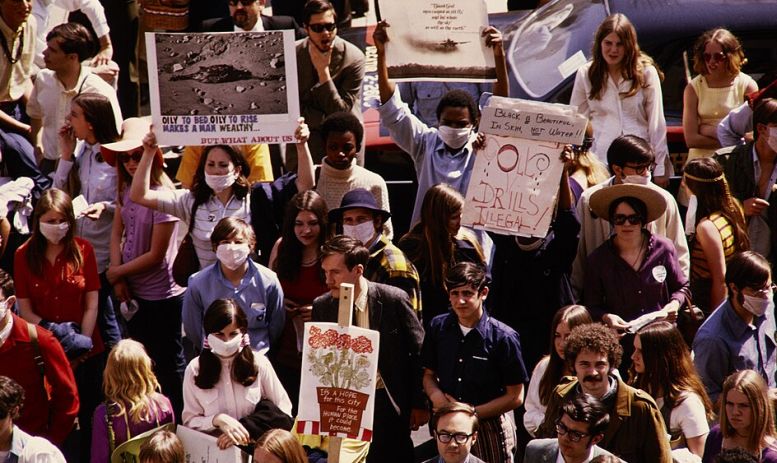

The EPA was won through mass struggle, culminating in the 20-million-person strong protests on April 22, 1970 for the first Earth Day. These protests combined mass outrage against environmental destruction with creative organizing tactics from the student anti-war movement and the organizing muscle of the labor movement. While watching Trump’s horrific attacks on the environment (and everything else) we should study the first Earth Day to learn how to fight back.

Unions & The Early Environmental Movement

In the decades following World War II, capitalism entered a protracted boom, but at great cost to the environment. Driven by the profit motive with no pollution laws to stop them, capitalists poured chemicals into rivers and belched poisonous gas into the air. Yellow smog and falling ash coated American cities. The air in New York City and Los Angeles was so polluted you could touch it. The famous 1969 Cuyahoga River fire wasn’t even the first time that river had caught fire. It had already happened a dozen times previously.

While the newly-prosperous middle class fled to the suburbs, the working class was forced to stomach this pollution, developing higher rates of asthma, cancer, and birth defects in the process. In response, workers looked to their own organizations—the unions—to fight against environmental disaster.

From the 1950s to the 70s, unions played a leading role in the environmental movement, and the United Auto Workers (UAW)—a union whose members built polluting cars—spearheaded this fight. In fact, in 1957, the UAW, International Union of Electrical Workers (IUE), and the United Papermakers and Paperworkers organized a campaign against a nuclear power plant in the suburbs outside of Detroit, in what one scholar argues was the first known grassroots protest against nuclear power.

Workers saw pollution both at work in the factory and at home in their communities, and used their unions to fight back against both. In 1968, the United Farm Workers initiated a campaign against the use of pesticides, arguing that they both harmed farm workers and the environment. In Detroit, Black auto workers in the League of Revolutionary Black Workers organized wildcat strikes in part against the terrible, polluted air in the lower-paid foundry section of the factories, where disproportionately Black workers had jobs.

The bosses often like to pit “jobs against the climate.” They say that workers in polluting industries benefit from environmental destruction, tying the industry’s profit to the wellbeing of its workers. Sometimes, business unionist leaders parrot this idea, like with the AFL-CIO’s support for the Dakota Access Oil Pipeline in 2016. Union involvement in the early environmental movement provides a powerful counter-argument against the climate versus jobs myth.

The Environmental Teach-In

During the 1950s-70s, the environment wasn’t the only thing on fire. In 1969, the anti-Vietnam movement was reaching its peak. On October 15, 1969, 15 million people across the country participated in the largest ever day of protest to that point. The power of the movement motivated everyone into action.

The “teach-in” was a key tactic to educate and discuss strategy for the anti-war movement. Under the impact of a growing wave of radicalization, the teach-in format was taken up by other struggles including the environmental movement. The spark for Earth Day came from a call by Democratic Wisconsin Senator Gaylord Nelson for a national day of “environmental teach-ins” on April 22, 1970.

This doesn’t mean the environmental movement was merely the brainchild of a Democratic politician, though. The Democrats are a party of big business but, under the impact of mass struggle, individual politicians can be swept up by events and pushed farther than their corporate overlords would like.

Environmental movements had been developing for over a decade and, combined with the anti-war movement, gave Nelson such a push. Nelson had a confused approach, reaching out to both Republicans like California Congressman Pete McCloskey and student radicals like Harvard dropout Denis Hayes who initiated the group Environmental Teach-In. But once the date was set, it became a rallying point for the already existing environmental movement to converge and grow into something more substantial.

For his part, Denis Hayes reached out to thousands of student organizations, community groups, and unions to organize Earth Day actions. The UAW played an instrumental role in financing and supporting Environmental Teach-In, donating $2,000 to get it off the ground and a lot more to print materials for Earth Day itself.

Because they had such a small team, Environmental Teach-In trusted local organizers to try out different actions. On April 3, 1970, they purchased a full page advertisement in the New York Times, calling for people to organize actions on April 22, 1970 which they called Earth Day.

During the week of April 22, 1970, twenty million people engaged in Earth Day protests. Local organizers planned a wide array of actions on Earth Day. Protests and teach-ins were held on 2,000 college campuses, in 2,000 community centers and in 10,000 high schools across the country. Unions mobilized their members to actions.

At the University of Michigan, the birthplace of the “teach-in”, 50,000 people packed into their basketball arena for a teach-in. There, among other speakers, UAW president Walter Reuther gave an emboldened speech about the role of unions in the environmental movement. In Manhattan, protesters set out picnic blankets on Fifth Avenue, which was shut down to traffic. In San Francisco, activists dumped oil into the reflecting pool at the offices of Standard Oil.

In New Haven, students interrupted a teach-in organized at Yale to appeal for support for the jailed New Haven Black Panther Party members, connecting the environmental struggle with the Black power struggle. In Tacoma, Washington, high school students rode down a highway on horseback to protest automobiles. The 1970 Earth Day protests both shut down business as usual all across the country and educated a generation about the environmental crisis.

Importantly, Earth Day was just a launching pad, and environmental organizing continued after that. Environmental Teach-In renamed itself to Environmental Action (ENACT). The UAW’s 1970 Convention passed a resolution pinpointing pollution as a key bargaining demand. On June 12, 1970 UAW teamed up with ENACT and other environmentalist organizations to send a joint letter to Congress calling for “air pollution control standards so tough they would banish the internal combustion engine from autos within the next five years” to “guarantee every American a safer, cleaner atmosphere by 1975.”

The collaboration also went the other way; ENACT and young environmental activists supported the UAW in advocating for the Occupational Safety and Hazard Act in 1970. The early environmental/labor coalition demonstrated how sustained organizing could win significant reforms.

These gains were won under the hated Republican president Richard Nixon. Nixon was no environmentalist or secret progressive. Just a month earlier, he had called out the National Guard to crush the postal workers’ strike. The mass pressure of Earth Day forced him to make concessions.

In July 1970, he proposed the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency and it began operation in December. The power of the early Environmental movement also forced the passage of landmark reforms like the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act in the next two years. These reforms drastically improved pollution in American cities and the lives of millions of working people.

The Climate Today

The 1970 Earth Day provides valuable lessons for the fight against climate change today, including how mass movements of ordinary people force change from below. The mass teach-ins—which involved millions from all sections of society—show the type of movement we need now. Today, one of our key chants at protests is “students and workers, unite and fight!”

The solidarity from the UAW with the environmental cause is a striking example of uniting to fight for a broader cause. The movement showed that, under the pressure of mass struggle, even a reactionary president like Nixon or Trump can be forced to pass wide-sweeping environmental reforms.

In 1970, UAW President Walter Reuther summed up the labor movement’s environmentalism. He said, “The labor movement is about that problem we face tomorrow morning. I mean, what good is a dollar an hour more in wages if your neighborhood is burning down? What good is another week’s vacation if the lake you used to go to is polluted and you can’t swim in it and the kids can’t play in it? What good is another $100 in pension if the world goes up in atomic smoke?” We in Socialist Alternative agree with him, and that’s why we fight for environmental reforms wherever possible.

However, Trump’s attacks on the EPA show that every reform won through struggle can be clawed back by the billionaire class. Today, the path towards environmental destruction has only been accelerated and exacerbated since the 1970s, so protecting the EPA as it exists today will not be enough.

Climate destruction is rooted in capitalism itself. Capitalism’s need for constant expansion places profits above any environmental concerns; this is true both with the horrific pollution in the 1960s and with the present-day climate crisis, which Trump is accelerating.

Alongside unions, immigrants’ rights organizations, and left groups, climate organizations should mobilize to a day of nationwide actions on May 1, specifically helping to organize student walkouts. Unions—especially those in polluting industries—should fight for a massive green union jobs program that would retrain workers faced with job cuts, as well as democratic public ownership of the top 100 polluting corporations. But to actually mitigate or even reverse climate catastrophe, capitalism urgently needs to be overthrown in order to implement a democratically-planned, just transition to 100% renewable energy as part of an internationally-coordinated effort.