Rob Jones is a member of Sotsialisticheskaya Alternativa (ISA in Russia).

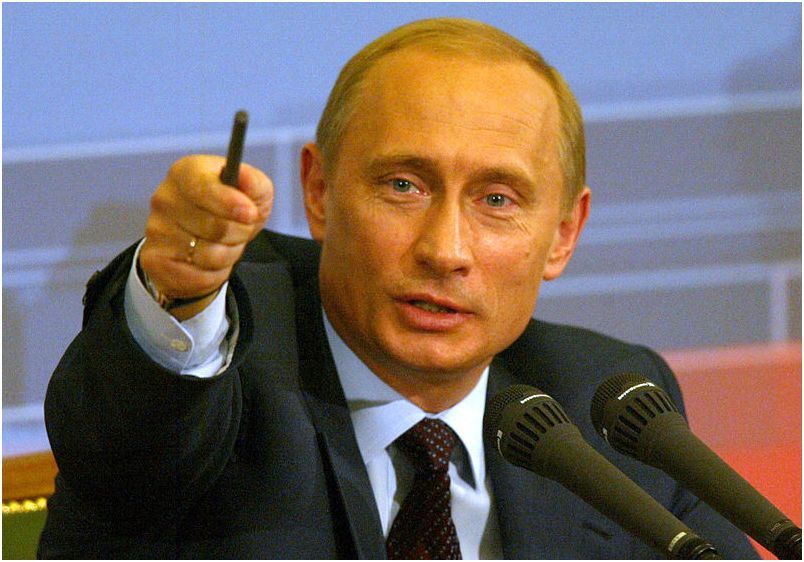

Twenty years since he was first appointed Premier by the outgoing Boris Yeltsin, Vladimir Putin in a provocative interview in the Financial Times recently declared that “Liberalism is dead”. His manifesto challenged the liberal capitalist elite currently dominating the European Union and rallied right-wing populists to step up their activities. The same week, he visited former Italian interior minister, Matteo Salvini. But his interview was also a warning to the domestic opposition in Russia that he will not tolerate democratic rights and liberal social reforms.

Crisis of the neo-liberal economy

To some degree, Putin is correct to say that the liberal economic model based on the Pinochet-Reagan-Thatcher model of neo-liberalism (initially termed ‘monetarism’) introduced at the end of the 1970s has failed. It replaced the post-war Keynesian economics that during the economic boom and under the pressure of mass working class movements, and the existence of an alternative form of society in the Soviet block, led to the introduction of the welfare state.

Neo-liberalism has meant continual attacks on the welfare state accompanied by increasing restrictions on workers’ rights. The capitalists made enormous profits not by investing in innovation and useful production but through privatisation, the commercialisation of the state sector and by financial speculation. Internationally, deregulation (i.e the removal of legal restrictions governing big industry) helped the dramatic growth of globalisation. There was a dramatic growth in inequality as the share of global wealth given to the working class declined.

When the bursting of the speculative bubbles precipitated the global financial crisis in 2008-9, governments retreated from the main principle of neo-liberalism – that the state should not intervene in the economy. Central banks in the US, EU, Russia, China and elsewhere provided huge resources to prevent bank collapses and support the economic interests of big-business. These bail-outs were accompanied by massive austerity programs aimed at reducing state expenditure and attacking workers’ living standards.

Putin has no alternative

The Russian capitalist elite personified by Putin however has no viable alternative to this economic model. They owe much to the neo-liberal approach adopted in the decade after the collapse of the planned economy destroyed by their bureaucratic mismanagement. Yeltsin’s shock therapy with the mass privatisation of former soviet industry to the new capitalists, many of whom were former young “communists,” members of the KGB or state ‘chinovniks’ (bureaucrats) caused an economic depression worse than in the 1930s. For a period, both hyper-inflation and a gangland style battle raged as the future oligarchs fought to concentrate huge wealth in their hands.

The Russian elite however, having asset-stripped the aged and inefficient soviet industrial base, was unable to develop a strong capitalist economy competitive on the world market. The anarchic nineties during which the elite encouraged maximum decentralisation and deregulation ended when Yeltsin handed over to Putin in 2000. His task was to restore order within Russia, and Russia as a world power.

Although Russia supplies of over a third of Europe’s energy needs, worth almost 100 billion euros a year, and, because of cheap prices is able to sell the advanced but relatively cheap military and nuclear energy technologies developed in Soviet times, little is invested in industry and services. The gains from these businesses go to support the bloated and corrupt elite. Since Putin came to power, the number of chinovniks has grown from one to two million!

State corporations and ‘national projects’

The Russian government has not rejected neo-liberalism completely. It follows a stringent budgetary policy which deprives healthcare, education and the skeleton social services of the resources they need. But it uses two significant strategies that contradict the traditional neo-liberal model. The first is state control over industry, particularly in the energy, defence and technology sectors through a network of State Corporations in which the state holds significant shareholdings and often unifying a whole industrial section into one corporation. Top managers are nominated and accountable to the government. At least a third of GDP is controlled in this way – about a half of all employees in Russia work in such corporations. These corporations in many ways resemble how wartime capitalist governments take temporary control over the defence industry and in no way represent a return of socialist planning.

Secondly, the government attempts to stimulate the economy using national projects supposedly to modernise high technology, healthcare and education. Some elite hospitals and universities have benefitted from new investment, but many others have been closed. Wage increases for doctors and teachers are accompanied by redundancies of large numbers of staff to finance the increases for the few. These projects are sucking money out of other sectors of the economy.

Global crisis

The global crisis hit Russia very hard. $1 trillion was wiped from Russian shares while GDP dropped by 7%. Fifty out of seventy banks were on the verge of collapse. While the US pumped in resources equivalent to 5% of its GDP to support its banks, Russia spent 11% of its GDP. Even though the fall in GDP was quickly reversed, it remained almost stagnant after, never since reaching the levels of pre 2008.

Support for the State Corporations was stepped up while the national projects gained importance. But to pay for the budget deficits this caused, 5,000 industrial objects were identified for privatization and a tough budgetary policy cutting money available for health, education and social services was followed. In effect a hybrid policy – state support and subsidies for the banks and business whilst the population suffered neo-liberal austerity was implemented. Living standards have now been declining for 6 years in a row.

Crimea, Eastern Ukraine and sanctions

Following the takeover of the Crimea, companies in the energy, arms and banking sectors as well as key individuals were placed on the sanctions black list – western governments stopped trading with them. Naturally, big business found ways around the sanctions. Turbines produced by Siemens even ended up in Crimea. In response, Putin announced a series of counter-sanctions, banning the import of a wide range of agricultural and food products. This has created a new business for the Russian mafia – smuggling cheese and other products into Russia.

Sanctions have not had a dramatic short-term effect on the economy but they contribute to the longer term stagnation currently affecting Russia. The government’s reaction is that this offers the opportunity to develop Russian industry. “Import-replacement” has become a new catch-word at the centre of a new government financed initiative. However, unable to buy modern technology, over 50% of equipment in the healthcare, energy and processing sectors has reached the end of its useful life.

Although for different reasons, this paints a picture of what would happen to many national economies if an extended global trade war develops.

Russia flexing its muscles internationally

But Putin’s challenge to the West is not just about economic models – it is about how power and influence is divided up across the world. Putin has expressed his regret at the break-up of the Soviet Union, hypocritically, as he himself played a large role in the process during which his family became very rich. His nostalgia for Soviet times was based, not on support for the planned economy and social welfare but on the strength of the military, police, KGB machine that in conjunction with the state bureaucracy destroyed the planned economy.

As the former Soviet elite converted themselves into the new capitalists they looked to the West for aid and encouraged the break-up of the former Soviet state. Putin himself in 2000 actively called for Russia to join NATO and for the construction of a greater Europe stretching from Lisbon to Vladivostok. The western powers extended their influence across Eastern Europe and NATO had air-bases in Central Asia and at one time even in Russia itself – in Ulyanovsk, the birthplace of Lenin.

But Putin inherited a Russia that was disintegrating. To stop the process going too far, he launched a brutal war to return the Chechen republic to central control and to warn other regions and internal republics that re-centralisation in the interests of the new capitalist Russia was now the order of the day.

Coloured revolutions

Once the regions were pacified, Putin moved to restore Russia’s influence over the former Soviet republics, many of which held deep scars of anti-Russian sentiment due to the criminal national policies of the Stalinist regime. Diplomacy and political battles waged between the EU/US axis and Russia. The west used investment, grants, the possibility of joining the EU. Russia exploited economic ties built in Soviet times and, of course, control over energy supplies as leverage.

Unable to compete economically, the Russian elite turned away from open collaboration with western imperialism, the Russian military adopted a strategy of hybrid warfare, combining conventional and cyberwar often with the use of “deniable assets” and the now notorious fake news and foreign electoral interventions. These methods are not new, indeed the imperialist powers became very skilful at their use, but the Russian regime has raised them to a new level.

Georgia was one of the first countries to experience hybrid warfare during the rose revolution in 2003. This was essentially an uprising of discontent at poverty and authoritarian rule that, in the absence of strong organised left forces became a struggle between different bourgeois forces for power. Both the US State Department, particularly under Hillary Clinton and the Russian Foreign Ministry used all the diplomatic and propaganda resources at their disposal to represent their interests. The short war between Russia and Georgia in 2008 left the two mainly Russian speaking regions of the latter – South Ossetia and Abkhazia – as Russian protectorates whilst ensuring a strong anti-Russian tendency in Georgia itself.

The CWI at the time had a very clear position: “The duty of Marxists was to stand against Russian imperialist intervention, as well as Georgian aggression and western imperialist meddling, and to tell the working class the truth … to take a clear independent class position, to point to ways in which the working class can rely on its own strength to solve its own problems, not relying on the forces of the capitalist state.”

The conflict between Western imperialism and Putin’s Russia reached a new height after EuroMaidan in Ukraine in 2013. The government’s rejection of an aid deal from the EU in favour of one from Russia provoked an explosion of anger at poverty and authoritarianism, which they associated with Russia. The new pro-EU government with significant far-right involvement threatened to encroach on the rights of Russian speakers. The Kremlin exploited the widespread fear of this section of the population, taking over the Crimea and providing support to the right-wing warlords in Donetsk and Lugansk to enable them to maintain control and pressurise the Kiev government.

Marxists support the right to self-determination up to and including, as Lenin said, separation. We would go further, if the majority wants to leave one state and join another it should have that right. The best way of deciding would be a democratic referendum controlled by working people and by ensuring the rights of other minorities are assured. However, in today’s world in which there is a growing struggle between the different imperialist powers the establishment of new, stable independent states based on capitalism in which economic and social rights for the working class are guaranteed is not possible. Marxists have a duty to warn that unless the struggle for self-determination is run in parallel with the struggle against capitalism there can be no long-term solution of problems.

But as Lenin said – “the tree of life is ever green.” The majority of Crimea inhabitants if given a free and democratic vote would, in 2014, have voted to join Russia but Ukrainians and Tatars, making up about 30% of the peninsula’s population, would have opposed this. This reflects Crimea’s history. In 1954, the Kremlin transferred Crimea as a gift to Soviet Ukraine to strengthen the ethnic Russian population in Ukraine as a counter-balance to the strongly Ukrainian nationalist Galicia and Volynia provinces integrated into Soviet Ukraine in 1944. It also reflects bitter resentment by the Tatar population which had been returning to Crimea after 1991. Ethnic Russians only became a majority in Crimea after 1944 when the Tatars and other nationalities were violently deported en-mass by Stalin to Central Asia.

The Kremlin, of course, used the concerns of the Crimean population to deal a blow to NATO and other pro-western forces. Publicly claiming it was “righting an historic injustice” and defending the Crimean population from encroaching “nazism” Russian troops took over the Crimean parliament, sacked the government and appointed a well-known pro-Russian Mafiosi as Premier. They rushed through a referendum, suppressing any opposition from Tatar, human rights and left activists before extending its hybrid war through East Ukraine with, in Putin’s own words, the aim of restoring Russian rule across NovoRossiya – formerly a region in Tsarist Russia spreading across South Ukraine and Moldova as far as Rumania. The Kremlin’s plans were checked due to a lack of support in East Ukraine, the economic cost and for fear of an open confrontation with NATO forces.

In such a situation, a resolution of the national question is complex and can only be tackled by recognising the right of self-determination combined with strong working class organisations unified across ethnic lines, to ensure a democratic decision making process and to guarantee the rights of minorities. Recognising the right of the Crimean majority to join Russia, a correct approach would have warned of the consequences on a capitalist basis and offered a socialist alternative – the struggle to overthrow capitalism in both Russia and Ukraine and establish a democratic socialist federation in the region and beyond.

Without this, we warned there may be a temporary improvement of the economic position in Crimea as the Kremlin pumped subsidies in, but this would be accompanied by the introduction of authoritarianism to the peninsula. But by taking over Crimea, the Kremlin would strengthen its reactionary base at home –a massive wave of patriotic propaganda and repression lasting several years in Russia itself resulted.

Those from a Stalinist tradition naturally present Russia as a new “anti-imperialist” force and, turning a blind eye to the Kremlin’s reactionary policies, gives it uncritical support as the lesser evil. They and their fellow travellers argued support for a yes vote to join Russia in the Crimean referendum. Instead of independent working class action, they recommended the Kremlin as a saviour for the Crimean working class. Even worse, such a call would cut socialists off from the working class in the rest of Ukraine, Baltic states, Poland and other East European countries.

Following the Crimea takeover, the Kremlin started to flex its muscles further afield. Lacking the economic power of the Chinese state, it uses its military machine, dealing significant blows to western interests in Ukraine and Syria but increasingly, by intervening in conflicts in the Central African Republic, DRC, Sudan, Yemen and elsewhere. Russia, second only to the US is aggressively selling armaments abroad and scandals around the use of “deniable assets” – military contractors are unfolding. In common opposition to Trump, the Kremlin finds itself cooperating in some fields with China even to the extent of organising large scale joint military manoeuvres. This cooperation, however can quickly turn into its opposite if interests dictate.

‘Liberal’ social attitudes under attack

Putin claims liberal social attitudes – civil and human rights, democracy, secularism, gender and racial equality, freedom of speech and organisation – which he sees as western influences have also outlived their time. Even in the best bourgeois societies the granting of these rights has been inconsistent – their application depends on wealth. Most social and democratic rights had to be fought for by the working class, trade unions and other forms of struggle. Equal pay for women, for example, has never been achieved in any capitalist country.

Now these economies are reeling under the effects of the global crisis, they too are retreating to more authoritarian methods of rule with restrictions on trade unions, more repressive policing and so on. At the same time, the bourgeois institutions and political parties in particular, are becoming increasingly discredited. This process, in the absence of strong left political forces is both feeding the support for right wing populists such as Trump, Johnson and Salvini and is being further fed by these demagogues.

Socialists and liberal values

Socialists stand at the forefront of the struggle for civil and human rights, democracy, secularism, gender and racial equality, freedom of speech and organisation if, for no other reason than it will be impossible to build a strong, working class revolutionary force without attention to all these issues. We have a proud tradition to follow. The Bolsheviks in 1917 went further than any bourgeois democracy at that time. All persons over 18, male and female, were given the right to vote excepting only the rich bourgeois and exploiters – elsewhere workers, the poor, women and the youth were not allowed to vote. Large steps were taken to at least formally introduce equality of women with men. Homosexuality was decriminalised. The church and the state were separated and the obscene wealth of the church confiscated to help feed the starving during the famine provoked by civil war. Nationalities were given the right to self-determination. Unfortunately, these gains were reversed during Stalin’s political counter-revolution as the bureaucratic caste from which Putin himself was later to emerge seized power.

Democracy in Russia was discredited in the 1990s as the restoration of capitalism went under the name “restoration of democracy.” Instead the masses received privatisation, unemployment and hyperinflation. The Putin regime, which benefited from that fraud, now attacks the bourgeois liberal opposition in Russia for promoting “western values.” Of course these liberals too support democracy and freedom only as long as their free market, that is capitalism, is allowed to operate without restrictions.

Socialists argue that genuine freedom and democracy is only possible when society is free of exploitation and repression. In defending democratic, social and national rights in authoritarian societies, a mass movement of workers and youth organised through trade unions, workers’ committees and other democratic structures is needed to organise a revolutionary constituent assembly that can lay the basis for the creation of a new society.

Putin and authoritarianism

Putin is quite happy to praise Stalin and publically regrets the break-up of the Soviet Union – but he hates the ideas of Lenin, Trotsky and the Bolsheviks who wanted to establish a genuinely democratic and free society. His support for Stalinism is only for the most reactionary features of his rule, he has not the slightest sympathy for socialism in any form. When he talks of the death of liberalism, he is not regretting the failure of liberal capitalism to ensure human rights and ensure living standards but gloating over the fact that the more developed capitalist countries are moving towards more authoritarian rule.

The CWI warned in 1990 that the new Russian capitalism would not be like that found in the European Union. The economy would be reliant on the export of natural resources and the democracy would be similar to Latin America with its succession of weak democratic rule and military /authoritarian regimes. We were wrong to predict that the wealth of the top 1%, which at the end of the Soviet era was 4-5 times higher than that of the general population, would reach the Latin American figure of 14 times higher. It is now more than 20 times higher! Corruption has reached pandemic proportions – in 2008 the average bribe was 9,000 rubles, today it is nearly 250,000 (3,300 euros). In these conditions, the Russian ruling elite cannot afford a genuine bourgeois democracy, instead it uses managed democracy in which only safe parties are allowed to run in stage managed elections and any opposition is meet with repression.

But Putin’s rejection of liberal ideology is not just based on economic reality. Trotsky explained that the Stalinist bureaucracy overturned the revolutionary ideas of the Bolsheviks replacing them with reactionary conservative values once held by Russian tsarism. Putin too supports the conservative values of the Russian orthodox church, perhaps the most reactionary of religions. Orthodoxy should be central to society with a patriarchal relationship between church and state, the state and family and within the family – views summed up by Archpriest Vsevolod Chaplin, church spokesman who believes Putin should be “royal emperor” and scrap democracy, describes Russia’s war efforts in Syria as a “holy battle,” supports Stalin’s murderous purges and, needless to say, thinks “feminism is very dangerous.”

In reality, other right populists have similar views. Jair Bolsonaro is a national conservative, against homosexuality, abortion, secularism although his economic program demonstrates elements of neo-liberalism. Trump, Johnson, Salvini, et al may each pay homage to different religions, but each has essentially the same backward views supplemented by a strong dose of reactionary nationalism. Putin’s aim of creating a global conservative coalition is only possible based on common ideological positions or using Russia’s traditional partners such as Assad backed up by military support.

With a new global crisis looming there is another problem. In 2008, neo-liberalism was still the dominant ideology of the global bourgeois. It was able to coordinate a relatively united response to the banking and finance crisis using the institutions of globalization including the IMF, World bank and EU. As the crisis has eaten away at the economic basis of global capitalism and increased inter-imperialist tensions, it is already not as capable of dealing with another crisis. The growth in support for the new populist right with their national conservative ideologies mean that in a number of countries there are leaderships who will oppose further global cooperation.

A socialist alternative is needed

It would, however, be wrong to view the choice facing humanity today as one simply between neo-liberal and national conservatism. The environment is crying out for the large monopolies to be taken over and managed not in the interests of private profit, but in a sustainable planned way in the interests of the whole planet. Young people, women, the LGBT community and the working class as a whole need a society free of religious backwardness and prejudices, in which they can control their own lives. A world in which wars are an unhappy memory in the past, and authoritarian and imperialist leaders no longer fuel the global arms trade. We need a society in which all the latest technological advances are used not to create even more oligarchs but used instead in the interests of all working people. To do this means having no faith in current world leaders, instead building powerful organisations of the working class and youth, capable of taking over political power and building a genuine, democratic and internationalist socialist society.