It’s 6 years since Michael Moore’s last film, Capitalism, a Love Story. He’s back on top form, perhaps a little less strident (a good thing), and still showing his trademark qualities of righteous but witty indignation combined with a populist style and message. From the title, you might think this latest documentary is a critique of American foreign policy. Only indirectly. The film’s premise is that, after decades of invasions that have brought no tangible benefits to Americans, the US needs to consider a different approach – so Moore goes along to the Pentagon to persuade the Joint Chiefs of Staff to give the troops a well-deserved break. Instead, Moore will get the opportunity to travel to various countries across the world to wage a series of one-man “invasions”. The twist is that instead of colonizing oil and mineral resources he will stake a claim for the best practices of each country that can then be “exported” back to the US.

How would you like 8 weeks paid holidays?

He begins in Italy talking to a couple about the holiday entitlement that goes with their job. Moore is amazed to find out that they get 8 weeks holiday a year and he contrasts this with the sad situation for workers in the US. The management of the company where the couple work are also interviewed and they come across as super happy to be granting so much vacation time to their workers – after all, contented, rested workers are more productive. The good part of this section is that there is also an interview (too brief) with a union militant who argues that none of these gains have been conceded willingly but have required a struggle by the workers, first to win them and then to defend them. The not so good part, and this is a common weakness of Moore’s films, is that he unnecessarily exaggerates, cherry picks or even misrepresents, to make a good point. In this case, the norm for Italian workers is not 8 weeks holiday – they are entitled by law to 20 paid days vacation plus 12 public holidays, i.e. 6 weeks and 2 days although there are some cases where unions have negotiated more. That fact, in itself, is good enough to contrast with the pitiful entitlement of US workers (as he points out, there is zero legal entitlement in the US to vacation time.) True but a misrepresentation in that he seems to be suggesting that US workers work 52 weeks a year only having statutory holidays off. Why give his many right wing critics this ammunition to claim that Moore “is distorting the facts”?

Lands of cordon bleu school lunches and no homework

From Italy, the next “invasions” are to three countries where the theme is education. In France, he discovers that school lunches in the public system are not only free and nutritious but are prepared in house in cordon bleu style. Moore tries tempting the kids with a Big Mac and Coke but the kids won’t “bite”. Next, he visits Finland, the country that comes in on most counts as having the best education system in the world. There he finds that kids get virtually no homework, have no standardized tests, and actually spend less time in school than their peers in other countries (777 instructional hours per year versus 900-1,000 in US). In Slovenia, he discovers that post-secondary education is free – no tuition fees and virtually no student debt.

Then comrades come rally

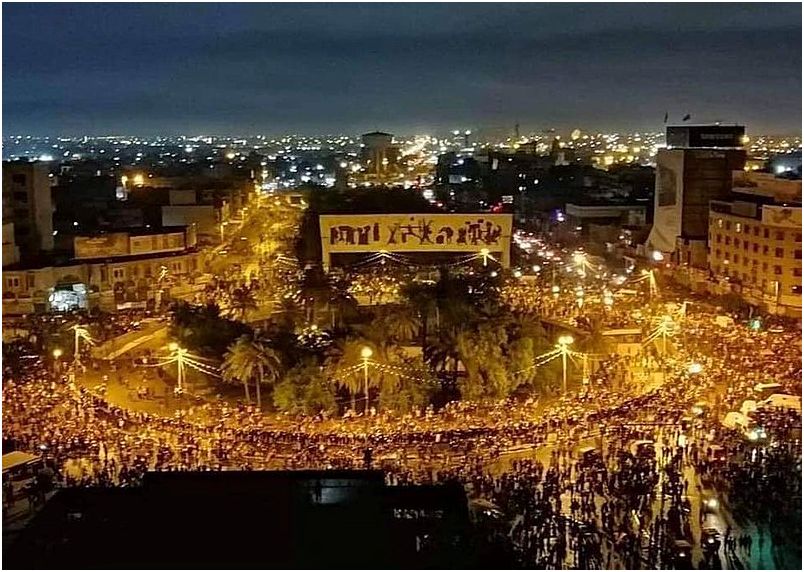

In Germany, he deals with the country’s willingness to face up to and learn from its dark past. He contrasts how the German school history texts openly take up the Nazi past while their US counterparts fudge the issue of slavery and black oppression. In Iceland, Moore exalts in the way the government dealt with the aftermath of the 2008 financial crash – arresting and imprisoning the Icelandic bank CEOs. In Iceland, he also advocates for their forward-thinking approach to women’s rights. Likewise in Tunisia. In Portugal, he learns of that country’s progressive handling of drug addiction where they have decriminalized the use of all drugs and the emphasis is on treatment centers and rehabilitation. This approach has led to considerable reduction in drug related crime. And in Portugal, we get a scene to warm the hearts of all socialists – a lusty singing of The Internationale at a May Day rally.

Ideally American

Moore makes many good points but he has this trait of indulging in some rose-colored romanticism of other countries and their policies. This comes out in the interviews he conducts with politicians, industry leaders, educators, and the general public. The same applies to his idealization or mythologizing of what he calls “American ideals”. He concludes by claiming that the policies adopted by many of the counties he “invaded” were influenced by early American ideals. For example, he sees the generous Italian vacation entitlement as catching up to and going beyond what had been started in the US with the struggle for an eight hour day in the 1880s. “They weren’t European ideas”, says Moore. “They weren’t new ideas. They were ours.” While it is valid to trace the gains of workers across the world to particular struggles at particular times in particular places, it would be a gross distortion to attribute this to an “ideal” unique to one country. That is akin to today’s Britons claiming democracy as their own, based on Magna Carta.

A movie for Bernie?

Moore is under the illusion that the post WW2 social democratic, “welfare state” model of many European countries (which, despite the attacks of neo-liberal, pro-austerity governments, still retain some of the progressive achievements of the post war era) can be transferred to the US in 2016. That is the problem – under the conditions of 2016 capitalism, they cannot.

Yet despite Moore’s misguided optimism, this a film well worth seeing and its left wing, funny, populist message will resonate with many. Indeed, a shortened version would would go down very well at a Bernie Sanders rally.