Robert Bechert is a member of the Committee for a Workers’ International.

G7 failure, penalty tariffs reflect capitalist world disorder

G7 failure, penalty tariffs reflect capitalist world disorder

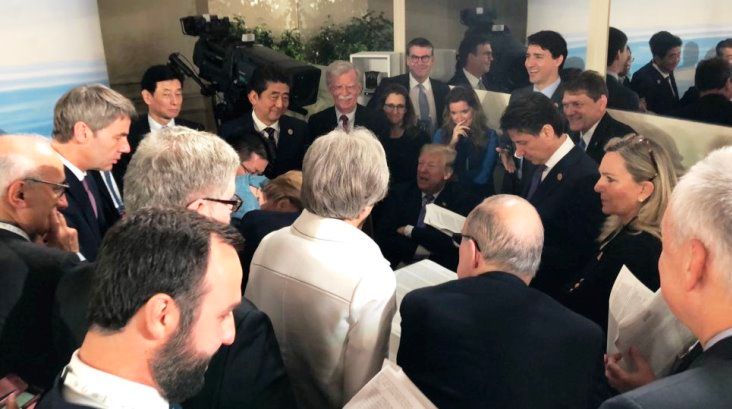

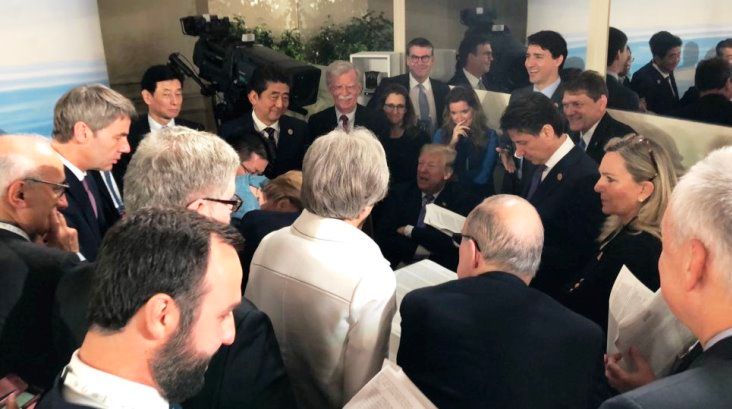

Trump’s claims of success after his Singapore meeting with Kim Jong-un were in complete contrast to the downbeat mood amongst most of the other leaders who had been with him at the preceding G7 summit in Canada.

This G7 marked a descent into a weakened get together as the meeting could not hide the deepening divisions against amongst the older imperialist powers, something not seen since these meetings started in 1975. This collection of key capitalist leaders really had nothing to say on the key issues facing the world. The G7’s decline was sharply symbolised by Trump withdrawing US agreement with its final communique. This largely token example of Trump’s “America First” policy was followed up by something more significant, the imposition of extra tariffs on a range of Chinese exports to the US.

These steps, along with the earlier imposition of extra duties on steel and aluminum imports to the US, have increased fears amongst Trump’s opponents, and some key sections of US business, that these penalty tariffs could trigger a trade war, or at least a slowing down of the world economy. Taken together these steps, and other developments like the Russian regime reasserting its role in the Middle East and elsewhere, are opening up a new chapter in world relations.

The clashes between individual leaders were not just the result of Trump’s bluntness, ego, making up his own fake “facts” and rapid switches of policy. More fundamentally they reflect the changes taking place in world political and economic relations as rivalries and instability increase at a time when the international economy has still not escaped from the consequences of the crisis that began in 2007/8.

A key fundamental has been the rise of newly capitalist China as a world power and the relative weakening of US imperialism. This decline is one reason Trump is using tariffs against China, historically the leading power in any epoch has stood for free trade, due to its dominance of the world market as Britain did in the nineteenth century. Additionally the international strategic dominance which the US enjoyed after the collapse of the former Soviet Union is over. But, despite China’s rise and increasing international role, the US is today still the world’s leading economy and the predominant global military power.

Other ingredients to this volatile international mix are the sharpening of environmental issues, like water supply, and how some countries are experiencing rapid population growth that is also changing regional balances of forces, while sharply posing the question of what the future holds for tens of millions of young people.

Especially for young people the future character of work is being posed by the far-reaching structural changes which are taking place both in national economies and in the world economy as technology and digitalisation further develop. A key question will be who benefits from these changes, the capitalists and a small elite or the mass of humanity. Currently many of these developments are being used to boost profits and sharpen competition at the expense of workers.

Against this background the world economy has been growing again, albeit at a slower rate than before the 2007/8 crisis. However much of this growth is based upon the use of debt to try to overcome the continuing after-effects of this crisis. Just in 2017 total world debt rose by over $20 trillion to $237 trillion, equivalent to $30,000 for every human being on the planet, something which has given rise to fears of a new financial crisis at some stage.

Simultaneously the European Union (EU) is faced with its own issues of tensions between its members, the effects of Brexit, preventing a renewed euro currency crisis, dealing with the impact of the migrant inflow and its own relative international decline. It was not accidental that at the G7 the new Italian government was the only one appearing to be sympathetic to some of Trump’s positions.

All this has resulted in sharpening contests between the rival powers to maintain, or increase, their share of a slowly growing and more intensively competitive market. Trump’s “America First” is a striking example of this, but he expresses more openly and crudely what all the capitalists aim for. Trump’s administration does not mind the instability its actions are creating, they view it as striking their rivals off balance and freeing US imperialism from some of the constraints brought about by working jointly with other powers. But the US ruling class is far from alone in pursuing their own interests, currently it is Trump who is simply more blunt in saying it. German imperialism is currently generally more circumspect in the ways it seeks to steer the EU, although it was brutal when it came to bringing Greece to heel in 2015.

Trump is also always looking to keep his domestic base secure, most of his tweets are aimed at them, a regular diet of boasts of what he has “done”, nationalism and populist attacks on those who oppose him. Alongside right wing support, a significant part of Trump’s base are those whose living standards were falling already before the recession and felt left ignored by what they saw as an elite establishment. Thus Trump keeps promising to “make America great again”, bring back good quality jobs and hypocritically attack those fellow members of the US ruling class who dare to oppose him.

But, in many ways, the situation in the US is not unique. Around the world there is anger and alienation that is undermining existing institutions and structures, including parliaments and political parties. Already in many countries before the 2007/8 crisis, years of neo-liberal attacks and setbacks for the workers’ movements had resulted in a growing polarisation of wealth and undermining of living standards both for the working class and sections of the middle class.

Since then the long crisis has bitten further into living standards, “atypical” working (fixed term contracts, casualisation, government enforced cheap labour schemes etc.) spread and increasing numbers could not see a prosperous future. In fact increasing numbers feared that their children and grandchildren would have lower living standards and worse life prospects. On top of this anger grew amongst many at the idea of paying the price for a crisis that demonstrably the ruling class could not accuse the working masses of causing. The fact that many of the banks, which are popularly seen to have triggered the 2007/8 crisis, have returned to making huge profits will only reinforce this bitterness.

A further source of bitterness is that the recent limited economic growth has not, in many countries, resulted in sustained real rises in workers’ or middle class incomes and conditions. Currently Germany, the largest European economy, has its highest ever employment total, but the trade unions estimate that around 20% of workers are in the low wage sector.

This is at a time where internationally there has been a continuation of a huge polarisation of wealth. The “Quantitative Easing” (QE) policies many governments carried out in an attempt to mitigate the impact of the crisis actually also served to further enrich the ruling class. In Britain the Bank of England estimates that the richest 10% of families each benefited on average by £350,000 thanks to its QE operations between 2009 and 2014, meaning each got around £1,345 extra income every week, and have certainly gained more since then.

After the crisis’s onset country after country saw protests, whether in terms of industrial battles, mass demonstrations or the birth of new political movements. However, so far, these developments have not led to decisive change. This is largely due to those leading such movements lacking a program that, or not being willing to, challenge the capitalist system. This failure, most strikingly seen in the betrayal of the SYRIZA leaders in Greece in 2015 when they agreed to implement austerity policies, has often opened the way to the growth of right populists and far right parties. These forces sometimes actually mentioned genuine questions/fears but gave false answers often coated in a reactionary, nationalist propaganda.

Trump’s own victory was partially rooted in disappointment that Obama’s “hope” promise did not materialise for many Americans and along with the pro-corporate rottenness of Clinton’s campaign. While Trump represents a section of the US ruling class, his takeover of the US Republican party and the presidency is a reflection of how many national ruling classes have, at least for now, lost their grip over political events in their own states. While, in the past, capitalist politicians and state machines have not been simple marionettes of the ruling class they generally have represented their broad interests, something which is not now the case with the current governments of the US, Britain and now Italy.

But events do not develop in straight lines. Trump’s victory itself has spurred on opposition within the US, it should not be forgotten that he lost the popular vote in 2016 and that Trump obviously fears future electoral defeats. He is desperate to hold his base together, present himself as an “outsider” and is ready to blame others for all his failures.

Trump’s crude tactics, often based on divide and rule both domestically and internationally, can themselves increase turmoil and provoke rapid changes.

Despite its international character, much enhanced by globalisation, capitalism by its very nature is rooted in the nation state, something that produces rivalries, clashes and is the source of repeated conflicts and wars. Before the Second World War this was even the case between erstwhile allies. It was only in 1939 that the US military stopped updating its ‘War Plan Red’, a plan for a possible military conflict with Britain, and even then this plan was retained for a number of years. Obviously there is no prospect of a war between the US and Britain now, but history still plays a role today. Thus as part of his “America First” propaganda Trump recently blamed Canada for burning down Washington DC in 1814 even though it was actually an invading British army which was responsible.

For decades after 1945 capitalism was challenged globally by Stalinism. Stalinism was not socialism but a totalitarian regime that grew out of counter-revolutionary developments in Russia in the 1920s and 1930s. However for decades it remained a system that was not based on a capitalist economy. For a time, especially after1945, the capitalist powers feared that the transformation of countries like Russia and China would be seen as an example that alternatives to capitalism were possible. The existence of non-capitalist, albeit Stalinist, states provided a glue which generally kept the major capitalist powers’ rivalries and conflicts within check. But after the collapse of Stalinism in the former Soviet Union and in Europe, followed by the transformation of China into a special form of state capitalism, this glue has dissolved. This is partly why Trump and his supporters feel that this is the right time to launch a counter-offensive against those rival capitalists profiting at the US’s expense.

But it is not only Trump’s policies which are causing disruption. Tensions are escalating again within the European Union not simply over the question of migration but also again over the eurozone’s future, especially on how to deal with a renewed banking crisis which is widely seen as a distinct possibility. The EU can also be faced with Italy and some other EU countries at least tilting towards Trump in order to get leverage against Germany and France, something which would be a recipe for deeper clashes.

Not since the 1930s have international capitalist divisions been so open. While direct military clashes between the major capitalist powers are very unlikely at this stage, the possibility of more regional conflicts, proxy wars and, later, perhaps even skirmishes between US and China forces cannot be ruled out.

Of course in these conflicts there is layer upon layer of hypocrisy on all sides. Capitalist media in countries feeling the sharp end of Trump’s attacks have criticised his failure to mention human rights with Kim Jong-un, but often fail to mention their own governments’ silence over human rights in Saudi Arabia and the other Gulf dictatorships.

The polarisation taking place within the US shows how Trump’s policies, enrichment of his own family and personal behaviour are all provoking opposition. At the same time the combination of limited economic growth and huge jumps in many companies’ profits in the US is beginning to encourage workers to press their demands. Significantly total US trade union membership grew by 262,000 last year, and three-quarters of the new members were under 34 years old. This year has already seen a wave of teachers’ strikes, often organised from below by the rank and file, demanding extra spending on education alongside better wages and conditions.

Both in the US and internationally there are popular fears that Trump’s policies, despite his friendly meeting with Kim Jong-un, could lead to renewed military conflicts, especially in the Middle East. This, alongside his reactionary politics, will be an important factor in the mass protests which will greet Trump’s July visit to Britain.

But in the US itself the growing interest in socialism reflects a search for a way forward for society. Amongst those looking for an alternative there is an understanding that the victories for the right, first George W. Bush and now Trump, were the results of popular disappointment with Bill Clinton’s and Obama’s presidencies. Trump’s victory, like right wing successes in other countries, was linked to the traditional Republicans and Hilary Clinton both not being able to answer the right populists and nationalists, along with the far right, who exploited popular fears and anger.

This is why building a socialist alternative to the turmoil and disruption of capitalism is so necessary. There will be struggles over important issues like living standards, oppression, the environment and democratic rights along with protests against the policies of capitalist politicians. Policies and strategies to win these battles are vitally necessary but to achieve lasting change they need to be linked to building, or re-building, a socialist movement independent from, and opposed to, capitalism. This means having the perspective of ending capitalism, taking the key economic resources into public ownership and beginning to democratically plan the use of human talents and the world’s resources in the interests of humanity and not capitalist profit which Socialist Alternative in the US attempts to bring into the movements developing there and which other activists in Committee for a Workers’ International similarly argue for around the world.

G7 failure, penalty tariffs reflect capitalist world disorder

G7 failure, penalty tariffs reflect capitalist world disorder