Climate change is global. But that doesn’t mean that all parts of the world are affected equally. To be sure, over the years, Canada has had its fair share of climate incidents such as forest fires and floods in Western Canada, hurricanes in the East, summer heat waves across the South, and ice storms in Québec and Ontario. The impact of these events has included deaths, displacement of people and loss of property. April is often referred to as “the cruellest of months” (from The Wasteland by TS Elliot). It can be construed as weather-related but is more often referring to the disappointed hopes that follow the onset of spring in the previous month.

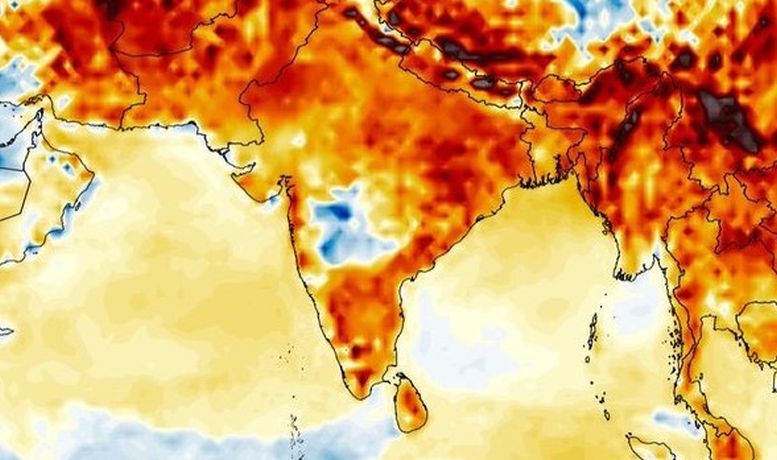

Heatwaves in Asia

However, for the people of India and Asia, this past April was indeed a cruel month — weather-wise. The following is the usual generic advice for visitors travelling to India in April: “Days are usually hot with balmy evenings, so visitors should pack light and cool clothing. The average daily maximum is 34C and the average daily minimum is 26C”. May is typically the hottest month, yet the impact of climate change and global warming showed up early this year. Large parts of the country reported temperatures higher than average and heatwaves began as early as March 3. Over 60 percent of India recorded above-normal maximum temperatures on April 18, 2023. Thirteen people died from heatstroke at a government award function in Mumbai on Sunday, April 16.

Last year, India experienced a searing heatwave where parts of the country reached more than 49C. By July, India had recorded 24 heatwave deaths. But it’s not just India that’s suffering. Asia, as a whole, is experiencing weeks of “endless record heat,” with sweltering temperatures causing school closures and surges in energy use. Record April temperatures have been recorded at monitoring stations across Thailand, Myanmar, Laos and Vietnam, as well as in China and South Asia. The Guardian reported that “in Thailand last weekend the authorities advised people in Bangkok and other areas of the country to stay home to avoid becoming ill. Temperatures hit 42C in the capital on Saturday, and the heat index — meaning what the temperature feels like combined with humidity — reached 54C.”

The rich have their air conditioning

Many have had to brave the hot and humid weather — sheltering under umbrellas and carrying fans to stay cool, or seeking refuge in air-conditioned malls. However, air conditioning in homes is a luxury available mainly to the rich — only 12 percent of Indians can afford it, not surprising since the average electricity bill consumes about 11 percent of average income in India, compared to 6 percent in Canada. The hot weather contributed to record electricity consumption in Thailand, with the country consuming more than 39,000 megawatts on April 6 — higher than the previous record of 32,000 megawatts in April last year. The rich can escape the ravages of heat waves with their swimming pools and air conditioned homes. They can also escape the country itself during the hottest periods. The poorest of the poor, on the other hand, suffer the most, especially those who are dependent on agriculture or fishing — some 42 percent of the population.

The Guardian report points out that in the Philippines, the heat affected schooling: “the school calendar shifted during the pandemic, meaning students now spend the hottest months of the year in their classrooms. Hundreds of schools have switched to distance learning to prevent students from falling ill, while one teacher’s group has called for shorter teaching times and smaller class sizes to ease conditions. Last month, more than 100 students were treated in hospital in Laguna, south-east of Manila, due to dehydration after taking part in a fire drill when temperatures were between 39C and 42C.”

Breaching the 1.5C threshold

For many Canadians, complacency can kick in when it comes to climate change — it may just be a question of the resignation and optimism that goes with “April showers bring May flowers.” For the people of Asia, it’s not so simple. March and April heat waves have brought more intense heat in the May that follows. And it’s not a question of gentle showers — in line with the experience in many other parts of the world, rainfall in Asia is increasingly taking place in short, intense bursts. Extreme rainfall events are increasing both in intensity and frequency. Forecasts suggest El Niño (warm water in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of South America) will return later in 2023, exacerbating extreme weather around the globe and making it “very likely” the world will exceed 1.5C of warming above pre-industrial levels. Scientists have warned that this could have dire consequences. The hottest year in recorded history, 2016, was driven by a major El Niño. A recent report from the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) warns that the world is almost certain to experience new record temperatures in the next five years, and that they are likely to rise by more than 1.5C. The WMO concedes that the breaching should only be temporary. However, they say that “it would represent a marked acceleration of human impacts on the global climate system, and send the world into uncharted territory.”

And in North America. . .

Large parts of the US’s Pacific North West in mid-May saw some daily averages up to 17C above normal. Temperatures in Seattle climbed close to 32C. Historic data shows there have only been six years since 1948 when May temperatures reached this level, and they have never occurred this early in the month. In Western Canada, the situation is no different. At the time of writing, extensive wild fires have led to a state of emergency in Alberta. British Columbia, Saskatchewan and Northwest Territories are also having an early start to wildfire season.

The scenes from the 2016 Fort McMurray fire were apocalyptic, but were no surprise to the scientists who had been predicting for decades that wildfires in Canada would continue to grow in size and intensity. Fire seasons are starting sooner, lasting longer, and the overall area burned is steadily increasing. The conditions for intense fire seasons — higher temperatures, increases in lightning activity, and dryness — are all being driven by human-caused climate change.

While in China. . .

Reuters reported that the major Chinese cities have issued heat advisories, “with Beijing expected to swelter in 36 Celsius temperatures on May 22. China is bracing itself for record-breaking heat that could threaten electricity supply, crops and a fragile economy. The people have suffered from heat waves in several regions since March with Yunnan province in the southwest, known for its mild weather, recently suffering temperatures of more than 40 Celsius. This has put a huge burden on the power grid as millions of homes switched on air conditioners.” As with India, the heat waves are occurring ahead of the regular summer season, which is particularly worrying for agriculture. Crop damage could drive up food prices, exacerbate inflation, and put pressure on China’s economy as it tries to rebound from a three-year zero-COVID policy that stunted growth.

And Europe. . .

The headline for Italy was: “Death toll mounts in Italy’s worst flooding for 100 years.” The elaboration was as follows: “[t]he floods in the northern Emilia-Romagna region have claimed 13 lives as of Thursday evening. An estimated 20,000 have been left homeless in a disaster that caused 23 rivers to burst their banks and 280 landslides, engulfing 41 cities and towns.” As with the other areas covered in this article, what stands out is not the weather phenomena as such but the intensity of them and their occurrence at times earlier than usual. The president of the Italian Meteorological Society observed that “[t]he only new thing to say about the latest floods is that two records were broken in 15 days in the same region. An event like the one that occurred on 2 May might happen once in a century, but then another hit 15 days later — having two occasions of intense rain within such a short time frame, and in the same region, is what is really surprising.”

And Africa. . .

In Somalia, torrential rain, coming on top of the country’s worst drought in four decades, has forced 250,000 people to leave their homes. Early in May the Shabelle River burst its banks, causing devastation to the central Somali town of Hobyo, displacing almost the entire population. A resident in the town, Jamal Ali Abdi, commented: “The water was up to my neck. Our entire family, including my six children, sought refuge in a relative’s home after our house was immersed. I was barely able to get my children to safety and grab a couple of items as we fled. We haven’t seen flooding on this scale in years. No one saw this level of devastation coming.” Nearly 250 million people have been forced to leave their homes after heavy rainfall in Somalia and the Ethiopian highlands led to flash floods that washed away homes, crops and livestock, and temporarily closed schools and hospitals in Beledweyne, the capital of Hiiraan region. The flooding disaster has come on the heels of its opposite — a drought that had been inflicted on the country since October 2020. Now there will be thousands more added to the 216 million people the World Bank predicts could be compelled to move within their own country by 2050 because of climate stress.

Fight for socialism

Whether climate change manifests itself in wildfires in Canada, floods in Italy, or heat waves in India, the important thing is to recognize that, in all three cases, capitalism is to blame. This is bigger than solar panels and electric cars. We cannot wait for green capitalism to save us, because it won’t. There is a time bomb ticking and we’ll need a major mobilization of the working class, the poor, and oppressed to defuse it. The crisis calls for an international, working-class led socialist movement to demand actions like bringing the fossil fuel industry into public ownership and reassembling it for green energy production. Our planet depends on such a movement developing.