The False Hopes of Carbon Capture Schemes

Some of the biggest polluters in the world, along with governments, have been betting the house on a quick technical fix to solve the problem of ever-increasing carbon emissions. That fix has been around a long time and goes by the name of Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS). In the Canadian province of Saskatchewan, long time bragger of being a world leader in CCS technology, the fix is becoming undone. The 115 MW carbon capture and storage unit that began operations at the Boundary Dam coal power plant in October 2014 was the world’s first commercial scale, “clean-coal” unit. But a recent report shows that the plant continues to miss emissions reduction goals, raising questions about the cost-effectiveness of the technology. “We don’t think carbon capture works as well as industry and promoters claim,” said David Schlissel, an analyst who wrote the report for the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. “We don’t think it’s a good use of money to keep coal-fired power plants running.”

Proponents originally said the process would capture up to 90 percent of the Saskatchewan plant’s carbon emissions. That would amount to about a million tonnes of carbon dioxide a year — the rough equivalent of emissions from 200,000 cars. That goal has never been reached. When all the plant’s emissions were factored in, the average capture rate was 57 percent. A 2022 report on carbon capture backs up the findings. “[The project] has not sustained the design rate beyond a dedicated capacity demonstration completed in 2015.” Capture is limited by both technical issues and the demand for carbon dioxide from the energy industry. The latter uses the gas to extract more oil from depleting reserves. Yes, that’s right — captured CO2 is compressed, transported and used to extract more oil or it gets injected into deep geological formations. Today, the lion’s share of the CO2 captured from industrial processes doesn’t go back into the ground. Instead, 60 percent of it is used to extract more oil, and they call it by the benign name of “Enhanced Oil Recovery” or EOR.

Elsewhere in Canada

A National Observer article reports that “other carbon capture projects have yet to reach their stated goals. Altogether, there are seven CCS projects currently operating in Canada, mostly in the oil and gas sector, capturing about 0.5 percent of national emissions. CCS in oil and gas production does not address emissions from downstream uses (e.g., emissions from the driving of cars). CCS is expensive — as much as $200 per tonne for currently operating projects — as well as energy intensive, slow to implement, and unproven at scale.” Shell’s Quest project near Edmonton has stored nine million tonnes of CO2 at a lower-than-anticipated cost. But its capture rate of 77 percent remains below the 90 percent originally announced. Capital Power has announced that the company would no longer pursue its $2.4-billion carbon capture project at its Genesee power plant in Alberta. The CEO, Avik Dey, said, “Fundamentally, the economics just don’t work. Hopefully, the technology will improve, and we can revisit this when the economics improve.” The socialist answer to Mr. Dey is that, hopefully, it will never be revisited. If the technology and economics improve, and that technology were used for more oil drilling, that would be a disaster for the planet. This would lock the world into an ongoing vicious cycle of capture/compress/drill.

Another Shell project, announced in June, sees it moving ahead with a pair of CCS projects in Alberta. Shell has not disclosed anticipated costs of either project. But they’ve admitted that the recent approval of the federal carbon capture sequestration tax credit — meant to help jump-start carbon capture projects — was also key in their decision to proceed. It has been revealed that this tax credit, according to the independent parliamentary budget watchdog, could cost $1 billion more than the federal government originally estimated. It is clear that the Feds have deep pockets when it comes to funding Big Oil.

The world: India, China, the US

The poor track record of CCS in Canada is part of a broader trend. According to the Global CCS Institute (2022), the global growth of carbon captured by commercially-operating CCS facilities has been much slower than anticipated. As of September 2022, only 30 commercial CCS projects are operating across all sectors around the world. Most proposed projects have been withdrawn: of the 149 CCS projects anticipated to be storing carbon by 2020, over 100 were cancelled or placed on indefinite hold.

The two countries that are most dependent on coal are India and China. Coal is burned to produce 71 percent of India’s electricity. In China it is 61 percent. India wants to add at least 53.6 gigawatts of coal-fired power capacity over the eight years ending March 2032, in addition to the 26.4 gigawatts currently being constructed. Bloomberg reports India is set “to keep exploiting its vast coal resources and deal with its growing emissions.” To match increasingly steep demand peaks and avoid blackouts, aggressive renewable deployment is not enough, said Rajnath Ram, a government energy adviser. “In the absence of storage, you need to add at least the same amount of thermal capacity. We have abundant coal and we want to use it, in a sustainable way.” The power sector generates 42 percent of India’s total emissions. Ram estimates that 70 percent of that can be captured and recycled through carbon capture but the Saskatchewan experience does not bear that out.

China, another relative newcomer to carbon capture projects, has around 40 demonstration projects in operation or under construction, with a total annual capture capacity of around 3 million tonnes per year. Carbon capture has become a focus area for China’s major power generators, as the country pursues a plan to hit its carbon emissions peak by 2030. The Globe and Mail reported that last year, state-owned oil and gas giant Sinopec launched a 712,000-tonne-per-year capture project — the country’s largest — at one of its oil refineries in Shandong province. The new project involves capturing CO2 produced from Sinopec’s Qilu refinery in eastern Shandong during a hydrogen-making process, and then injecting it into 73 oil wells in the nearby Shengli oilfield. Sinopec has estimated that 10.68 million tonnes of carbon dioxide will be injected into the oilfield over the next 15 years, boosting crude oil production by nearly 3 million tonnes. So, they capture CO2 in order to boost oil production and then they claim this is sustainable and will help to achieve getting to net zero (the balance between the amount of greenhouse gas that’s produced and the amount that’s removed from the atmosphere). What planet are they living on?

The majority of projects in the CCS facilities pipeline are located in North America. In the United States, despite significant industry and government investment in the technology, more than 80 percent of proposed CCS projects have failed to become operational due to high costs, low technological readiness, the lack of a credible financial return, and dependence on government incentives that are withdrawn.

Subsidies

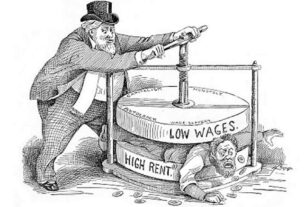

Both business and governments consider (CCS) to be a primary emission reduction solution, but there is little evidence on the efficacy of this approach and its consistency with Canada’s net-zero commitment. Despite this, the federal government provides substantial support for CCS, having committed at least $9.1 billion of public subsidies to date, alongside $3.8 billion from the governments of Alberta and Saskatchewan. Industry is seeking further public funding. By 2030, Canada’s CCS Investment Tax Credit is estimated to provide double the subsidy amount offered to CCS from the US government. If those combined government subsidies were used to invest in green energy, 13,000 commercial scale wind turbines could be deployed, enough to power 19 million homes.

Enhanced Oil Recovery – squeezing out the oil to the last drop

CCS in the oil and gas sector is used to lower emissions from production, and therefore covers only one side of the equation, representing about 15 percent of those fuels’ total life-cycle emissions. Production-side CCS does not reduce emissions from the end uses of oil and gas, which represent the largest share of life-cycle oil and gas emissions.

There are currently seven operational CCS projects in Canada, five of which are related to the oil and gas sector, which capture an eye-watering 0.5 percent of national emissions. A recent example is the Alberta Carbon Trunk Line, a major network of pipelines for transporting CO2 captured from a refinery and an ammonia plant to declining oil fields in Alberta, where it is used to enhance oil recovery (EOR) by “revitalizing” old oil fields and “extending the life of mature fields by several decades.” The CCS project at the North West Sturgeon Refinery had a similar goal. Another example is Shell’s Quest project, which has been operating since 2015 and produces blue hydrogen (hydrogen produced from natural gas with CCS) that is then used to upgrade bitumen into synthetic crude. Additional blue hydrogen projects are in the works, such as Suncor and ATCO’s joint venture to build a $4 billion plant to produce blue hydrogen — 65 percent of which would be used in Suncor’s Edmonton refinery.

The primary potential application of CCS in Canada’s oilsands would be capturing emissions from natural gas combustion (used to generate steam to facilitate bitumen extraction or upgrading). Yet this form of emissions capture is in its early days. About 65 – 70 percent of CCS projects globally capture emissions from natural gas processing. Further, approximately 70 percent of the carbon captured in existing CCS facilities in Canada is used to increase the production of aging oil fields through EOR. CCS is, therefore, facilitating continued Canadian oil and gas production — which the industry expects to grow by nearly 30 percent above 2020 levels by the end of the decade.

Around the world, 73 percent of the carbon captured is used for EOR. Proponents of CCS have repeatedly over-promised on the technology’s ability to reduce emissions, and CCS projects have under-delivered.

To live up to advocates’ promises, carbon capture has to work nearly perfectly all the time. “If you’re going to try to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by capturing CO2, you’ve got to capture almost all the emissions and you’ve got to do it year in and year out for decades. Carbon capture has not done what its proponents claimed it would do,” said David Schlissel.

From Net Zero to Socialism

The path to net zero is estimated by Bloomberg economists to be US$215 trillion worldwide by 2050. Even with that amount of spending, it is likely that global temperatures will be higher than 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. The Paris agreement of 2015 committed 195 nations to “hold the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.” Among the big changes needed to achieve net zero, every new car sold from 2034 onwards will have to be an electric vehicle. That’s another story. Ford Canada announced in April that it would postpone all electric vehicle production at its Oakville assembly plant in Ontario by two years until 2027 due to “softening demand.” We can see where that’s going. The Financial Post reports that CCS will require US$6.8 trillion worth of investment to trap emissions from both industry and the power sector.

The International Energy Agency, in its report The Oil and Gas Industry in Energy Transition concluded with this statement: “Regardless of which pathway the world follows, climate impacts will become more visible and severe over the coming years, increasing the pressure on all elements of society to find solutions. These solutions cannot be found within today’s oil and gas paradigm.” Put another way, the days of oil and gas should be over but Big Oil does not see it that way. With taxpayer subsidies, they are happy to delude themselves that they can have their cake and eat it too by capturing CO2 and then produce more of it. The cake eaters will quickly discover that they can get more than indigestion. In fact, they can be permanently put out of their misery with the working class being mobilized to expropriate and run their businesses under democratic control. Then there will be no more carbon capture, no more oil extraction from land or sea — instead, there will be hope for a socialist future as we invest in clean energy and create green jobs.