Tom Costello is a member of Socialist Alternative (England, Wales & Scotland).

The British ruling class would like to present today’s capitalist “democracy” as one that was gradual, “peaceful,” and a kind gift handed down from above. “Once the poor had no rights, and then society naturally progressed towards the great democracy we have today because we were patient” as the narrative would go.

In reality, this totally skips over the real history. From its creation in the 1800s, the industrial working class came into existence ready to struggle against the effects of the capitalist system. The 1840s saw the emergence of a mass, independent, democratic movement of the working class: Chartism.

Roots

Mass movements of these types never fall out of the sky. Chartism grew out of some of the earliest struggles of the day. Workers in the towns and cities had moved to form “combinations” — early and primitive forms of trade unions — which the absolutely degrading conditions of the time had made an urgent necessity.

So widespread were the maiming and injuries by the brutal conditions of the factories and workhouses that Friedrich Engels, then a young factory owner in Manchester, commented that wandering the streets was ”like living in the midst of an army just returned from a campaign” (Condition of the Working Class in England, 1845).

The working-class majority were deprived of even the most elementary political rights. The Liberal government’s “Great” Reform Act had only given the vote to a mere 10% of the population — dismissing the mass as “unfit to rule.”

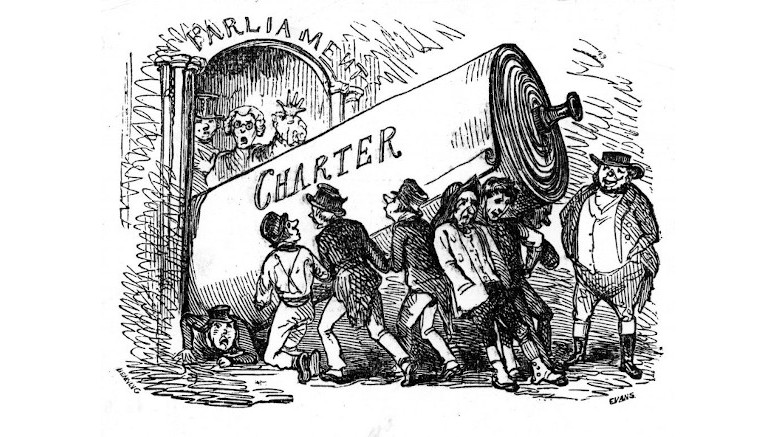

Because rich men could simply buy their way into Parliament, the working class had to find a way to push itself into the struggle for democratic political rights. The resulting document — the “People’s Charter,” centred around its six key demands (read in the box below) quickly gained support. It inspired unity in action between the disparate working-class campaigns of the time by setting out a program for the class to gather around in common struggle. The movement at one point reached massive heights, with 3 million signatures to the “People’s Charter” in 1842 — and it is likely that about 1 in 7 of the population signed it.

Revolutionary movement for reforms

When radicals, reformers and revolutionaries met to set up the first Chartist Convention in 1837, news spread rapidly. In contrast to Westminster — the parliament of the capitalists and landowners — here was a body made up of delegates elected at mass working-class meetings across the country — 300,000 gathered in Manchester, 150,000 and 70,000 in Newcastle for example.

It was these thousands of militant workers, confident in their power, that formed the base of the movement. With the tacit support or sympathy from millions of others, the worker-activists of Chartism mobilized regularly through this ten-year period to beat back the attempts of the capitalists to bring the movement under their control.

This was seen from the beginning. Side-by-side with the birth of Chartism was the establishment of the Anti-Corn Law League. This organization, made up of bourgeois reformers who wanted to relax free trade laws, made a direct appeal to the Chartist workers. If they were to drop their banner and join with the liberal capitalists, all of their problems would be solved by the low prices created by opening up trade. The movement was virtually unanimous in rejecting this idea and maintaining the need for total political independence from the forces that acted in the interests of the rival class.

Equally significant was the Charter itself. While it had some glaring omissions (for instance not calling for votes for women), it was still extremely revolutionary. The demand for annual parliaments — still not achieved today — was a case in point. An activated, confident and enraged working class exercising its right to hold elected officials to account on a yearly basis would have made the situation alarmingly difficult for the capitalists to maintain. Engels commented at the time that “These six points, which are all limited to the reconstitution of the House of Commons, harmless as they seem, are sufficient to overthrow the whole English Constitution, Queen and Lords included.”

A clash of methods

The Chartist movement was never simply about calling for the “right to vote” as an end-in-itself, although the more middle-class elements in the Convention tried to reduce it to this. It was about the working class organizing politically, to take over the power of the state, to introduce political changes in their own interests, to be achieved by any means necessary — “peaceably if we may, forcibly if we must.” Thus when the second petition in 1842 was presented to parliament, the statement said quite boldly: “The abolition of any monopoly will never unshackle labour from its misery until the people possess that power under which all monopoly and oppression must cease.”

But as with any mass movement, Chartism from the start was riven with debates and differences on the question of how to actually win its six formal demands. While all agreed that the demands needed to be won, it was inevitable that they would be overwhelmingly rejected by parliament (which they were). The question was, what would the movement do when this happened? One group, the “moral force” Chartists, who mostly represented better-off, skilled workers and small shopkeepers, argued that were the movement to follow the example of the more “mature” and “educated” and show self-restraint, the government would naturally concede.

Among the rank and file of the movement there was a totally different idea, however. The “physical force” wing, representing generally the mill workers, the miners and industrial workers, rejected any idea that the ruling class could be “morally” compelled to hand over power by voluntary means — they would have to be forced into it. These ideas, represented largely in the mass-circulation Chartist paper the Northern Star, stressed the need for the working class to use any and all means at its disposal to win its fight. The force of these ideas were seen in the mass general strike of the Northern industrial towns in 1842, and to the doomed but equally heroic 1839 Newport rebellion, where armed labourers prepared to launch an insurrection for power under the slogan “better to die by the sword than perish with hunger.”

While the employers, landlords and privileged middle-class began to arm, across the country working people in the industrial centres began obtaining arms and organizing military drills in anticipation of a civil war. Across the country state forces were murdering workers in their dozens. The “moral forcers” however were unable to stomach the idea of a working class prepared to defend itself from the violence of the state. Having first dominated the Chartist Convention, within a few months they had largely disappeared.

Either way, through organizing around the Charter, the confidence, expectations and sights of the workers were raised. Newspapers and journals sprang up with a mass input and readership. The National Charter Association, formed in 1840, gained the status of the first independent political party of the working class, with regular branch meetings, political discussions to educate its membership and wide-scale campaigning.

Also hugely significant for the time was the growing confidence of working-class women to enter the fray and express their demands politically. While the Charter itself omitted mention of women’s suffrage, women often played a leading role among the rank-and-file in the struggle. Mass meetings across the country were held specifically for the sake of women Chartists discussing their own place within the workers’ movement. It was also the female mill workers and weavers of Stalybridge, Lancashire (today Greater Manchester) that triggered the General Strike of 1842, compelling the male workers to follow their lead.

Quite naturally, these women saw no appeal in the ideas of the moral forcers. Not only was it the militant Chartist left that would recognize the need to extend the movement to the other half of the working population, but the meek ideas of the softer “moral forcers” would not match up to the task of fighting for the liberation of doubly-oppressed women workers.

Factions

Up until this point, the role of the working class in times of revolution had been mostly to tag onto another, more powerful class in the hope of political change. But the total lack of interest from the British ruling class in any type of reform smashed this idea to pieces.

As a result, the working class was finally independent but inexperienced in how to face up to the most burning questions of the day. Questions like “how can the workers achieve and maintain their rule?” couldn’t be answered by reference to a past experience — ideas had to be tested. Political understandings within the movement were diverse and often politically immature.

This was compounded by the fact that many sections of the working class at this stage had only recently been thrust into the polluted, disease-ridden and smoke-filled industrial cities. Many still remembered a time where they worked on the land, either as day labourers or small farmers. The prospect of returning back to this quieter, more peaceful and less bloodthirsty pre-industrial way of living had a perfectly understandable attraction, even if this were possible for the mass of the working class. This didn’t prevent some leaders from appealing to it, however. One high-profile and well-known leader of the movement, Feargus O’Connor did just this.

While O’Connor’s genuine devotion and commitment to the cause cannot be doubted, his privileged background within the Irish gentry meant he had a lack of political understanding and little theoretical depth. His revolutionary language was often not matched by action. On more than one occasion, for example, he called for general strikes which he failed to organize. In the later periods of the movement when the total hostility of the ruling class to all democratic rights became clear, rather than gearing up the movement for a new round of action, O’Connor retreated inwards towards the unsuccessful idea of escaping the towns and resettling on rural land, essentially moving in a utopian and escapist direction.

Birth of Marxism

There was also, however, the historic beginning of the growth of socialist ideas. One faction of the movement, represented by George Julian Harney and the London Democratic Association (LDA) — arguably the first revolutionary socialist organization in history, forcefully argued from a minority point of view for the Convention to not just be a gathering of activists, but a militant day-to-day leadership that could direct the movement against the power of the capitalist class.

The LDA had no illusions that the Charter could be won without a combination of class struggle and revolutionary leadership, and brought working class women like the Scottish socialist feminist Helen Macfarlane into its leadership. While others peddled the illusion of the working class either gradually taking over power or sharing power for a time with the capitalists, Harney’s group urged that the Convention declare itself an alternative workers’ government, with the power to end capitalist rule.

These ideas were of huge inspiration for Marx and Engels, who were closely involved with the movement from the mid-1840s onwards. Harney, along with Marx and Engels, went on to organize the Fraternal Democrats — an early attempt to form an international association of revolutionaries, which brought together the Chartist left, as well revolutionaries on the European continent. Eventually it was the revolutionary Chartist paper the Red Republican that had its place in history as the first publication to print the Communist Manifesto in the English language.

Conclusion

For all its great imperfections, the Chartist movement deserves its place in the history not just of the British working class, but the working class globally.

What was crucially missing at the time through no fault of the heroic activists and fighters of the movement was something that was yet to fully develop — the instrument of Marxism. But, by witnessing for the first time the working class entering onto the stage of history to play its own role in forcing events, Marx and Engels were able to integrate these experiences into what we now call “Marxism.”

They were to witness that in creating the working class, the bourgeoisie produced “above all, its own grave-diggers” as the Communist Manifesto pointed out. Here was a class that, even if it experienced defeats, had the weight and potential to cast capitalist exploitation into the history books.

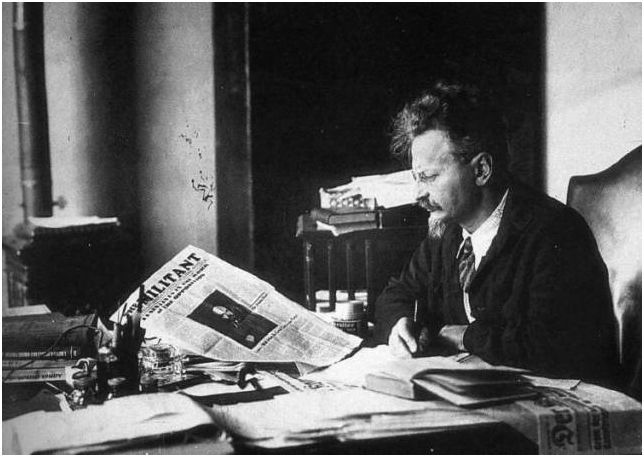

In 1926, in his article Where is Britain Going? the Russian Marxist and revolutionary Leon Trotsky said the working class in Britain “can and must see in Chartism not only its past, but also its future.” Almost a century on, this is no less true.

The six demands of the Charter:

- Votes for all men over 21

- Secret ballot (to protect workers from intimidation by employers during election time)

- No property qualifications for election (so anybody could stand)

- Payment of MPs (to allow workers to stand)

- Equal constituencies (to end vote-rigging)

- Yearly parliamentary elections