Albert Kropf is a member of Sozialistische LinksPartei (ISA in Austria).

Many want to drive a wedge between Marx and Engels for their own interpretations of Marxism and socialism. There is no either or, but only both together. Let us take a look at this in a brief foray into the wild life of Friedrich Engels.

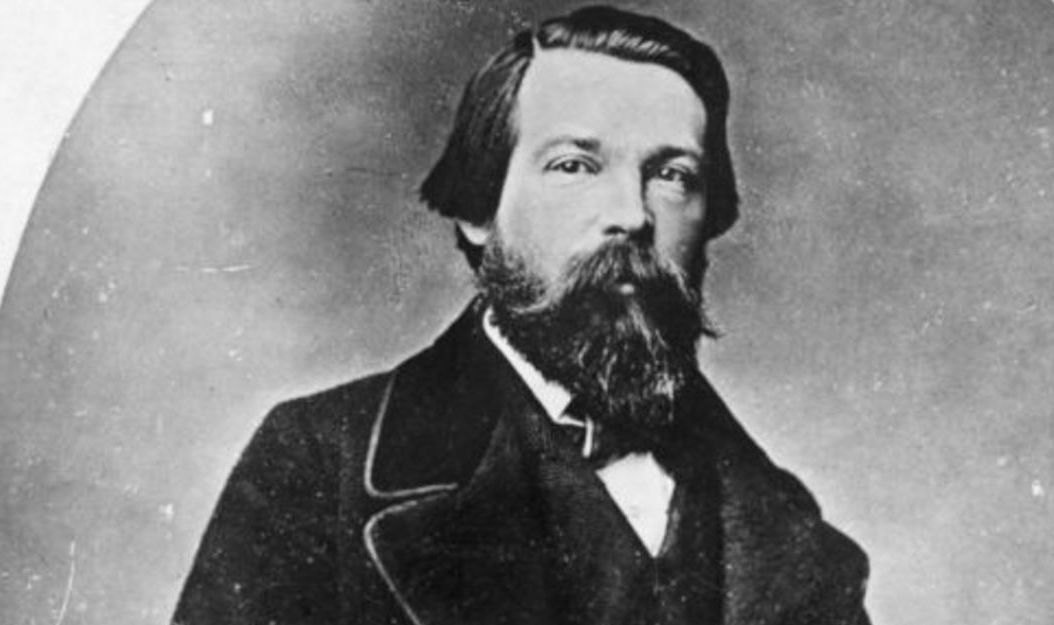

Whoever studies the biography and ideas of Friedrich Engels will sooner or later come across the quote of the “second fiddle”. In a letter to Johann P. Becker in 1884 after Marx’s death, Engels wrote: “Throughout my life I have done what I was made for, namely to play second fiddle, and I also believe I have accomplished my task quite passably. And I was happy to have such a splendid first fiddle as Marx.”

The question of the relationship between meaning and achievement when several people have created something together is not something that concerns only Marx and Engels. Quite the contrary. In all areas, whether sports, music, culture, or politics, the contribution of the respective participants is passionately discussed and is also argued about in retrospect. Lennon or McCartney as the driving force behind the Beatles, the changing roles within the Rolling Stones, Laurel and Hardy – and the list goes on.

The above quote forms a basis for a complex and varied depiction of Engels as a person and his significance for scientific socialism. On the one hand, it shows his complete lack of vanity in things like copyright or (intellectual) property, which is sometimes misinterpreted by biographers as general humility or a pietistic attitude towards life. But Engels was certainly neither humble nor pietistic. He was convinced of his opinion and fought passionately for it. Many of his political opponents will have perceived him, as they do with Marx, as being quite arrogant. He had thoroughly put aside the pietism (a form of Protestantism strongly influenced by the Enlightenment) of his parents’ house and enjoyed life to the fullest, alongside political work, in a manner that was unconventional for the time. On the other hand, especially those who are more or mainly concerned with Marxist theory and who “generously” leave struggle and the efforts of implementing Marxism to others, do indeed see in Engels the second fiddle. Everything that they do not like about Marxism, either practically or theoretically, they shove towards Engels.

We see something similar, only in reverse, on the social democratic and liberal side. Some people with a certain personal sympathy (such as the British historian Tristram Hunt) write for themselves a less politically radical and consolidated Engels, who fits better into their liberal, social democratic world view.

The unifying element on both sides is that they ultimately want to drive a wedge between Marx and Engels for their own interpretations of Marxism and socialism. There is no either or, but only both together. Let us take a look at this in a brief foray into the wild life of Friedrich Engels.

Barmen and Bremen

Today, Barmen is part of the city of Wuppertal in the federal state of North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. A little to the north lies the Ruhr area, for a little more than 100 years one of the European centers of the coal and steel industry. At a time when the Ruhr area was still covered with green pastures and was characterized by agriculture, Barmen was the center of the German textile industry when Friedrich Engels was born there on November 28, 1820.

Much has changed since then, not only in the immediate vicinity of Engels’ birthplace. A look at a map from around 1820 shows a completely different Europe than we know today and partly take it for granted. There was no Italy, no Belgium, no Netherlands, no Luxembourg, no independent states of Eastern and Southern Europe, nor a united Germany, but rather small states in countless principalities. Yet there were the Russian, Austrian and Ottoman empires: three great states, which were nevertheless past their peak. Furthermore, there existed Prussia as a consolidated great power, as well as England as the motherland of the Industrial Revolution.

It was the Europe of the Congress of Vienna. The great French Revolution had made huge waves far beyond France. On the shoulders of the French Revolution, Napoleon went from victory to victory on the battlefield until he was finally defeated by the united reactionary forces of Europe. This was followed by the redivision of Europe among the victors, which finally happened at the Congress of Vienna in 1815. However, it is not only the Europe of victorious reaction into which Engels was born in 1820, but also the Europe of the still living, rebellious spirit in the traditions of the French Revolution.

The Rhineland became Prussian only shortly before Engels’ birth, before then it was under French influence. Among the emergent bourgeoisie, the sympathies lay more with France than with Prussia. This was also the case with the Engels family, a still young entrepreneurial family in the textile industry. They stood for free enterprise and a self-confident bourgeoisie. Both were very formative for the young Friedrich. In contrast to his later political opponent in the fight for the minds of the workers, Ferdinand Lassalle, Engels always remained hostile to the Prussian authoritarian state. The father traveled to England, to Manchester, the world capital of the Industrial Revolution, and brought new production techniques back to Barmen. For this purpose, he founded the company Ermen & Engels together with the Dutch-born English entrepreneur Peter Albert Ermen. They ran a cotton spinning mill in what is now Wuppertal and one in Salford near Manchester. A German industrialist could hardly have acted more prudently and forward looking than Engels’ father at that time. But that doesn’t change anything about the poverty and the catastrophic living conditions of the workers, which Friedrich Engels witnessed from an early age.

He would never shake off his bourgeois background, for which he is often blamed today. Just like Marx, Engels does not come from the working class. In their later work and application of dialectics to the development of humanity, Marx and Engels refer to the complete suppression of the workers, both economically and culturally. The nascent working class could not “afford” its own ideology. It is dependent on “aid” from other classes and strata. Education is reserved for the bourgeoisie and nobility. At the time when little Frederick, reluctant and with problems of school discipline, was first attending school, child labor was almost a given for those outside of the aristocracy and bourgeoisie. Despite his privileged origins, Engels had to serve and work for what he called the “doggish commerce,” for his undoubtedly good livelihood and, in part, for that of the Marx family, whose quality of life was much worse. The accusation of the bourgeois origins of Engels and Marx is at best as naive as it is ridiculous, and completely misses the reality of the 19th century.

As the eldest son, Friedrich was designated to be the successor in his father’s company. In concrete terms, this raised the question of a training program appropriate for the job. It may be surprising from today’s perspective, but that was the reason why Engels actually had to leave secondary school against his own wishes before graduating. The entrepreneurs of the 19th century saw themselves as enterprising doers. A university education with the fields of study at that time was not an option at all and did not fit into this image and role. Economics and business management could not be studied but could only be acquired through relevant practical experience. Therefore, instead of studying, Engels started a commercial apprenticeship in Bremen. At that time, Bremen was a hub of world trade and a vibrant, cosmopolitan city. In addition to his technical and commercial training, he acquired basic knowledge in many languages, which was supported by the linguistic diversity of the global press available in the city. Today we would call Engels a polyglot; he wrote in over 20 languages, half of which he could also speak fluently. Even in his almost lifelong correspondence with Marx, both of them always jump back and forth between different languages. Engels’ passion for literature and journalism was also solidified in Bremen. He began to write and publish articles himself, albeit under different pseudonyms.

Arriving at Dialectical Materialism through Hegel and Feuerbach

After his apprenticeship, Engels completed a one-year military service in Berlin against his father’s wishes. During this time, he opted to live near the Friedrich-Wilhelm-University, today’s Humboldt-University. In addition to his military service, he attended lectures mainly on philosophy but also on East Asian languages. However, it would be shortsighted to see military service as a means to an end for Engels to attend the university. Military science didn’t relinquish its grasp on him and would also prove to be useful in practice, as it was in 1849 through his active participation in the revolutionary struggles. Later on, the question of how a revolution can ultimately be militarily successful would also be in the foreground for him. To this end, he researched and analyzed the German Peasant Wars of the 16th Century, but also current conflicts such as the US Civil War. He became a highly esteemed expert on military issues even in bourgeois newspapers.

But back to Berlin. In 1841, reactionary forces reigned there after a brief liberal phase. Especially among student circles, a subculture had formed in pubs, which consciously broke with backward-looking moral conventions. Among them was the young Engels, who would stay on this path for the rest of his life. Philosophically, this subculture finds its place in so-called Left Hegelian spheres, named after the German philosopher Georg Friedrich Hegel, who died 10 years before Engels arrived in Berlin. Hegel, in contrast to the spiritual rule of the church, took up the philosophical traditions of ancient Greece again. The focus was on understanding reality in its diversity, changeability and contradictoriness – dialectics. The Left Hegelians were forward-looking and had an approach critical of society and power. In contrast to this, the Old Hegelians pursued a conservative interpretation of Hegel in the direction of a “Prussian state philosopher.” In spite of all his progressiveness, even Hegel remained a philosophical idealist. Instead of God, he placed a “world spirit” that floated above everything. Hegel was an inspiration both for Engels and for Karl Marx, who had studied in Berlin before him. However, their paths did not cross in Berlin; by the time Engels arrived, Marx had already left.

To overcome Hegel’s philosophical idealism, Marx and Engels later developed dialectical materialism. The term combines the dialectic of Hegel, which we have already encountered, with materialism. This is a current of thought that stands in contrast to idealism. Both terms, materialism and idealism, have nothing to do with the way they are used in everyday language today. In principle, the question is whether the origin of everything is in thought (like something divine) or in matter (i.e. the real conditions). One of the most famous proponents of philosophical materialism was Friedrich Feuerbach. His basic thesis is that it is not our ideas that shape the world, but the world that shapes our ideas. In practical terms, this is clearly a rejection of religion; belief in a “higher power” is thus clearly idealistic. Materialism is to explain the origin and explanation of religions by means of external circumstances. Religion thus becomes a pure human construct.

However, in order to properly place constructivism (as we would call it today) in Feuerbach, Engels and Marx combined it with the dialectic of Hegel to form dialectical materialism. Accordingly, man is neither a pure product of religion, nor religion a pure product of man. It is both. In that people create religions for themselves, and these in turn influence people. People are therefore creator and product of religions at the same time. The application of this dialectical-materialistic method to society shows that the way things are produced and the distribution of what is produced determine the possibilities and the order of social life. Based on this, Engels and Marx now look at human history from these points of view and conclude in the Communist Manifesto of 1848:

“The history of all hitherto existing society is the history [that is written history] of class struggles. … in a word, oppressor and oppressed, stood in constant opposition to one another, carried on an … open fight, a fight that each time ended, either in a revolutionary reconstitution of society at large, or in the common ruin of the contending classes.”

The application of the dialectical-materialistic method is often somewhat simplified to “Historical Materialism.” Simplified because in the name the very important reference to the methodology of dialectic is lost and as a consequence it is often lost in the application. This can be seen, for example, in the abbreviations and the automatism of the “stages theory” of social democracy and later Stalinism. The mobile, flexible dialectical-materialistic method of thinking in contradictions and leaps gives way to a rigid sequence of social formations. The 20th century has (unfortunately) proved many times over that this is not just a “philosophical” discussion. After the February Revolution of 1917, the Mensheviks argued that the bourgeois-capitalist “stage” in Russia was now on the agenda and that the workers and peasants had to be satisfied with what had been achieved. Later, the Moscow bureaucracy under Stalinism demanded that independence movements in various countries, which were supported primarily by workers and the peasantry, be subordinated to the national bourgeoisie. In all cases, however, the majority of the bourgeoisie and its political representatives had reconciled with old or colonial rule, came to an arrangement, and ultimately stabbed the revolutions in the back. Countless people in China, Chile, Indonesia and many other countries paid for this with their lives in the 20th century.

In contrast to stages theory, the Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky picked up where Engels and Marx left off. The dynamics and development in leaps and bounds mean that capitalism has already brought the whole world under its rule at the beginning of the 20th century. A purely bourgeois revolution to impose bourgeois government and economy was no longer on the agenda, especially for the vast majority of the bourgeoisie. Even movements that at the beginning were strongly oriented on the ideals of civil liberties quickly reached the limits of the system and the movements could be brought to fruition only by transforming the revolution into a social one. Trotsky called this “permanent revolution” as early as 1905. Marx had come up with similar ideas before, and at the same time as Trotsky, for example, Rosa Luxemburg in her analysis of the Russian Revolution of 1905 and its implications for Germany and the policies of the SPD.

Formative Years in Salford

After the young Friedrich Engels had discovered politics and radical philosophy, his father sent him to England for further education, certainly also with the ulterior motive of freeing his son from “bad company” in the mind of Engels senior. On the way from Barmen to England, Engels made a short stop in Cologne in November 1842. The editorial office of the “Rheinische Zeitung” was located there, which increasingly became a mouthpiece for radicalizing classes. Here Engels met the editor-in-chief of the newspaper Karl Marx. It was not love at first sight. Marx saw in Engels a “classical” representative of what he considered phrase-wielding Left Hegelians.

Afterwards Engels continues his journey to Salford near Manchester. The “Victoria Mill” in Weaste, at that time still lay in a rather sparsely populated area. Today it is within sight of “Old Trafford” and the stadium of Manchester United. Important for the choice of location of “Ermen & Engels” was the proximity to the port, the canal and the important railroad line to Liverpool, by which the cotton reached the Manchester area. Here in the centre of the Industrial Revolution, Engels studied not only life, but also the grim reality of capitalism. He seeks contact with the working class, walks in dangerous streets and corners that are not of his stratum.

Cotton and its processing were the engine that drove the Industrial Revolution. Railroad construction, heavy industry, spinning mills, weaving mills – all this was compressed in cotton production and Engels was right in the middle of it all, while Marx was sitting in Cologne at the “Rheinische Zeitung.” Engels would get Marx to deal with economics, and he would eventually describe the creation of added value in capital on the basis of cotton spun into yarn. We can assume that Marx also came across the importance of cotton and its processing through Engels. In any case, we know from the letters of the two that Marx again and again got himself with Engels’ “commercial” – today we would say “economic” – advice.

But Salford is also important for the development of the young Engels for another reason. Engels knew the misery of the working class in principle already from Barmen. The important difference was the consciousness of the workers. In Manchester they had organized themselves and fought in the Chartism movement for concrete improvements such as the 10-hour day and the right to vote. In Barmen, Engels had given his political communist lectures to the bourgeoisie, perceiving the working class mainly as “suffering” rather than active. In England the working class was also suffering, but did not surrender to its fate. Later Engels and Marx will describe this essential difference in consciousness as a step from a “class in itself” to a “class for itself”.

In order to better understand economic processes, Engels read the founding fathers of economics David Ricardo and Adam Smith. To better understand social processes, he reads the French socialists Saint Simon, Charles Fourier and finally the British utopian communist Robert Owen. Like Owen, however, he did not only want to comment, but increasingly also intervene. He sought personal contact with the leading chartist George Julian Harney. He wrote not only for Marx’s “Rheinische Zeitung,” but also for the “Northern Star,” newspaper of the Chartists, the “New Moral” of Robert Owen and his movement. Finally, he made contact with the “League of the Just.” For its successor organization Engels and Marx will write the Communist Manifesto in 1848.

Salford is no less important for Engels for another reason. Here begins Engels’ relationship with two Irish-born sisters, Mary and Lizzy Burns. The role and influence of Mary Burns on Engels would be worth exploring more closely. The exact circumstances of the relationship between Engels and the Burns sisters are subject to many assumptions but little concrete information. Engels was very unconventional on many levels and did not live up to his time and status. It wouldn’t have been out of the question even in the 19th century, that men of Engels’ class employed people like the Burns Sisters’ in the house and had a sexual relationship with them. But what broke with all conventions was that Engels introduced and referred to Mary and then later, after her death, also Lizzy Burns as his wives. This is documented in a letter to Engels from the aforementioned chartist Harney, in which he explicitly sends greetings to Engels’ wife Mary. But the lifelong aversion of Marx’s wife to Engels is also based in it. When Engels took Mary Burns on a visit to Marx in Brussels and introduced her as his wife, she was horrified by this “social misstep” by Engels. Nevertheless, Engels was a part of the Marx family and a reference point for their children. After the death of their parents, their care for Engels went so far that they burned all letters that could have hurt Engels.

His affection and respect for the Burns sisters is evident in many things. The day before her death, Engels fulfilled Lizzy Burns’ final wish and formally married her. Engels left part of his fortune to a niece of the Burns’ Sisters, who were as much a part of his family for him as Marx’s daughters and their circle. Today it is certain that Mary Burns introduced the young Friedrich Engels to “Little Ireland,” the slums of Manchester. It is highly unlikely that Engels the “uptight snob” would have survived his research so unscathed without her. In both the Stalinist and Social Democratic portrayal, which in some cases already degenerates into “veneration of the saints”, the Burns sisters are diminished or excluded outright, which makes it clear that bourgeois moral concepts were deeply internalized there. There is no doubt that they had a great influence on his life. There is much to suggest an equal relationship, not least Engels’ support for her political activity for Irish independence.

Love at Second Sight and the Sprout of the Communist Manifesto

In Engel’s Salford days, the socialist movement was still petty-bourgeois, artisanal, and the workers’ movement and socialism were still separate branches. Engels was part of both. He researches the roots for the liberation of the working class from its misery. In 1844 he published the article Outlines of a Critique of National Economy in the German-French Annals of Arnold Ruge and Karl Marx. In it, Engels first takes a close look at the classic national economy of Adam Smith. In doing so, he shows that the free market economy, in contrast to the old economic order, does not mean freedom, but leads to a transition from the state monopoly to the “monopoly of private property.” The end result is not free competition, but the monopoly as social and historical reality. In his article, Engels also tries to link the connection between economy and society with the emerging materialistic science of history, which he got to know in Berlin. Two articles by Marx also appeared in the same issue. In these articles, Marx combines Engels’ less pronounced philosophy of history with Hegelian dialectics with regard to the working class. Ultimately, however, both were still up in the air in their essays and their approaches are not yet fully worked out. In the future, both would deal with the main points raised by the other: Marx with the political economy initiated by Engels and Engels with the application of the dialectical, materialistic method to the development of society and humanity.

First, however, they took a step back and dealt once again with a reappraisal of the Left Hegelians in the books later published as The Holy Family or Critique of Critical Critique and The German Ideology. To this end, an intensive and ultimately lifelong correspondence developed in advance as an exchange and comparison, in a kind of self-understanding of their ideas. On his journey home from Salford to Germany, Engels visited the Rheinische Zeitung again, which had already moved to Paris due to censorship. It was love at second sight! From then on, they formed a “two-man party” that lasted for the next decades until the end of their lives.

Back in Germany, Engels immediately set about processing the material he had produced in England and his experiences in the book The Condition of the Working Class in England. It was not the beginning, but the end of his era as a writer, although he will publish much more in the coming years. He did not want to be a writer in the form of a more or less neutral observer but as a participant in events. Even today we know the mantra of the bourgeois press of “non-judgmental, objective reporting.” Similarly, Engels describes the dawning revolution as an objective analysis of the development without any activity of its own. In his later writings, whether with or without Marx, Engels no longer writes as a “journalist” of this type, but as a political actor who intervenes in events and wants to push them forward.

In the meantime, Marx had also been expelled from France and moved to Brussels with kit and caboodle. Engels followed him there for a time and they founded the “Communist Correspondence Office” with connections in several European countries. In 1847, they joined the “League of the Just/League of the Communists” and fought against the utopian, communist majority current. Utopian because this communism – like that of Wilhelm Weitling – rather than being materialist, was religiously motivated. But it was also utopian because the role of the working class in the process of overthrowing capitalism was still seen as a subordinate, passive role. For the 2nd Congress, the two were finally commissioned to write a manifesto based on a draft by Engels (Principles of Communism); it became the Communist Manifesto. It was first published in February 1848 in Paris without making much of a buzz. In addition to the now rather meaningless reappraisal of their intellectual biographies and factional struggles, the Manifesto also contains many central theses for the here and now. These include the very concise presentation of the dialectical-materialist method on human history, the role of the working class, and the class struggle for the development of class consciousness, or from the class in itself, to the class for itself.

From the Revolution back to England

In the spring of 1848, many parts of Europe were already churning. For Engels and Marx, the advent of the revolution in Germany gave them the opportunity to return to their homeland. As revolutionaries, they wanted to intervene in events. Marx came from Brussels, where he was once again expelled, via Paris to Germany, where the revolution had already broken out in many cities and small states. He went back to Cologne and took over the post of editor-in-chief of the New Rhineland Newspaper. He traveled through Central Europe, giving lectures, fighting for the correct assessment and expansion of the revolution. This also led him to Vienna in September, where he gave the lecture Wage Labor and Capital at the “First Viennese Workers’ Association”. Then the liberal interlude is once again over. In September the New Rhineland Newspaper was banned and, after the suppression of the revolution, Marx was dragged to court and expelled from the country again.

Engels first took part in barricade fights in Barmen and Eberfeld until he finally joined the Baden uprising in southern Germany. After the defeat of the democratic republican federations, Engels was wanted by warrant. In the best case a long prison sentence awaited him in Germany, so a return to Barmen was not an option. He finally settled in Switzerland as one of the last fighters. His military experiences, especially the insufficiently trained republican fighting units, he would later review again and again.

First Engels followed his friend and comrade-in-arms to Paris and finally both went into exile in England more or less voluntarily. Marx did so also to continue his studies there. Engels’ father, in himself quite capable of suffering, had finally given him an ultimatum. Either he would return to the company in Manchester, or he would be figuratively kicked out of the family, possibly going into exile. Engels accepted the “offer” to earn money in Manchester as an executive and later as a partner.

In Manchester, Engels led a double life. On the one hand as an increasingly respected businessman and finally as a member of the local chamber of commerce, on the other as a revolutionary who was under surveillance. He lived with Mary Burns at various official and covert addresses in and around Manchester.

As a businessman, we would today rather refer to him as a manager, he had a clear, unfussy and quick way of getting to the point. Writing was easy and quick for him — two things that always impressed Marx. In addition, Engels’ well-organized way of working enabled him to handle a large workload on a daily basis. In addition to his professional activities, Engels was thus able to take on many jobs in and for the “two-man party.” In the following years a certain division of labour between Engels and Marx developed. Engels increasingly dealt with the translation of the theory developed by Marx into everyday language and with examples from everyday political events. To this end, he did something like public outreach work today, organized the deadlines and often wrote late articles himself under Marx’s name. Neither he nor Marx saw in this any disparagement of his achievement or role in their common cause. Rather, for him it was nothing much more than “party work.” Engels also wrote a lot during this period. Under pseudonyms he continued to write mainly letters, letters to the editor, and also articles for various newspapers. Since his time in Barmer and Bremen, he used the pseudonym Friedrich Oswald. Engels almost certainly attached great importance to his appearance, was well dressed and we can certainly call him “vain” in this respect. But in political matters he was by no means vain. Nor was it no loss for him to write letters or articles on behalf of others when it is important for the common cause.

Mary Burns died in 1863 at the age of 42. This is the beginning of the only deep and serious rift with Marx. He reacted to the news only casually and instead asked Engels for money. In a subsequent letter, Marx finally apologized for his misconduct, he was under great pressure because the court officer was in the house again and he could not stand by his friend as he should have done. Engels later goes on to have a relationship with Mary’s sister Lydia “Lizzy” Burns. Marx’s son-in-law Paul Lafargue writes about her:

“His wife, of Irish descent and a hot-blooded patriot, was in constant contact with Irish, of whom there were many in Manchester, and was always up to date with their plots; more than one Fenian (members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood) found accommodation in her house and thanked her for helping them … to escape the police.”

In 1869 Engels sells his shares in the company, having become financially more independent a few years earlier through his father’s inheritance. Now there was nothing to keep him in Manchester, he was drawn to Marx to continue working with him. Together with Lizzy Burns he moved to London the same year and they lived together until her death in 1878.

Anti-Düring and Marx’s Death

In the 1860s two different strands of the increasingly strong workers’ movement emerged in Germany. On the one side was the General German Workers’ Association (ADAV), co-founded by Ferdinand Lassalle. Today we would describe it as more social democratic rather than revolutionary. Lassalle sought reconciliation with parts of the Prussian nobility against the bourgeoisie in favor of reforms and assistance for the working class. Instead of a revolutionary overthrow and transformation of society, Lassalle emphasized an ever-greater penetration of society and the economy from cooperatives partly financed by the state. However, Lassalle died as early as 1864 in a duel over a countess by a bullet wound in the groin in Geneva, Switzerland. As a result, Lassalle’s original ideas lost influence and oppositional currents emerged, and even splits in some cases.

In 1869 the Social Democratic Workers’ Party (SDAP) in Eisenac was founded by, on the one hand currents in opposition to the ADAV and, on the other hand, splits from it, directly under the influence of the International Workers’ Association (The 1st International) co-founded by Marx and Engels. Included is Wilhelm Liebknecht, an old comrade-in-arms of Engels in the Baden Revolution and friend of Karl Marx. Marx would be godfather and namesake for his son, Karl. Due to his resistance to World War I as a member of parliament for the SPD, Karl Liebknecht was first sent to the front, then imprisoned, expelled from the party and finally murdered together with Rosa Luxemburg in the German Revolution of 1919 on the orders of the SPD.

The SDA received a surge in the number of unions, which Lassalle had more or less rejected. He justified this in his “iron wage law,” according to which class struggle ultimately makes no sense. After a period of open confrontation, a rapprochement of the two organizations began until the mid-1870s, which finally led to the unification in Gotha in 1875. Engels and especially Marx criticized the strong influence of the “Lassallians” in the program of the new party. During the same period, anti-Marxist and anti-Semitic tendencies increased within the party. This was expressed in the dissemination of the writings and views of private lecturer Eugen Dühring. One basis for his ideas lay in the lack of an elaborated image or blueprint for a future socialist society. Engels and Marx always emphasized that this could not be done on the drawing board, but only through class struggle. Dühring filled this gap in a society still strongly oriented by religious needs. As a political response, Wilhelm Liebknecht asked Engels to write a series of articles on the subject in the party newspaper Vorwärts (Forward). Engels complied with the request, read the subject matter in depth, discussed the main focus with Marx and wrote the articles. This finally resulted in the book Anti-Dühring in 1878 and in a revised form in 1880 as Socialism: Utopian and Scientific. Since then, both books have been considered classic works and foundations of Marxism.

However, the series of articles did not stick to his time. Quite the contrary, Engels shows himself to be very far and beyond the horizon of the time and importance of Dühring. This is reflected in many writings like the Anti-Dühring but also in The Part played by Labour in the Transition from Ape to Man from 1876. Among other things, he describes the devastating effects on the environment caused by the advancing industrialization:

“Let us not flatter ourselves too much with our human victories over nature. For every such victory she takes revenge on us,”

We see this revenge today very clearly in ecological catastrophe and the advance of climate change.

Karl Marx died in 1883 and Engels now had to take over his side of the party work. This includes the extensive correspondence within and outside the socialist movement. He was one of the few who knew the systems of the notes and records of Marx, who left behind thousands of handwritten pages. Together with Marx’s daughter Eleanor, known as Tussy, Engels structured, organised, and processed the political remnants of his friend works. First on the agenda was the completion and then publication of the 2nd volume of Capital. Then the 3rd volume. In part, he can only rely on notes, headings and discussions with Marx. He completes in the memory of his life-long friend and both of their political analysis and research.

In his popular publications, the late Engels frequently attempted to link the theory of dialectical materialism with the new groundbreaking discoveries of natural science.

In retrospect, these efforts don’t always seem as relevant due to the speed of scientific progress. To this day, it has led some to interpret the theories, for which Engels was a proponent, as outdated in their entirety. It is impressive, however, how the elder Engels kept his finger on the pulse, staying up to date with developments and discoveries.

The Origins of the Family

Marx was far from completing the most important projects he had been working on. He left a wealth of notes, fragments and annotations on books and texts that he had read in countless hours in the library of the British Museum in London. After his death, Engels and Tussy remained there to review and edit this mountain of manuscripts. With the Anti-Dühring he was able to close a significant gap, but others continued to exist. Over the years Marx had clearly also taken on an attempt to write a text on the relationship between state and society, but apart from notes he did not get very far. Engels himself had already addressed the connections between family, the state, and private property at various points in the Anti-Dühring. What was still missing, however, was a common framework spanning the subject area. This was provided by Engels in 1884 in his book The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State. Far ahead of his time, he provides, among other things, the explanation for the oppression of women in a class society and overcoming it under socialism.

European archaeologists have only recently discovered groundbreaking information about the way of life of the Vikings. Up until now, the Viking society was considered to be strongly gendered. Now it has been determined by means of new technical investigation techniques that many graves of rulers and fighters were actually women and not, as long believed, men. One reason for this wrong interpretation is that researchers sorted and ultimately presented their findings according to their personal conviction and also as a result of prevailing ideas and attitudes. However, this is not an isolated case. In 2020, an article was published by the renowned National Geographic Society that told of a similar case. In 2018 a 9,000-year-old grave was discovered in Peru. Inside was a rich arsenal of weapons and tools for hunters from the Stone Age. The gender, determined by the latest technical possibilities, was not as previously assumed. In this case it was a woman hunter as well. Further, subsequent research on the basis of other finds shows that about 30 to 50% of the big game hunters in the Stone Age on the American continent were women. Something that Friedrich Engels already derived and described in 1884 theoretically without even a hint of today’s technical possibilities!

Death

Engels died of esophageal cancer in his London apartment on August 5, 1895. In his will he included his housekeeper Louise Freyberger (formerly Kautsky), a niece of the Burns sisters, the Marx daughters and the SPD, to which he bequeathed 100,000 pounds. His brother was the only one of his blood relatives to inherit a picture of his father, who died in 1860. Engels himself remained childless, whether voluntarily or not, we do not know. The fatherhood he de facto accepted for Frederick Demuth, born in 1851, was a “favour to a friend.” In reality it was a child of Marx born out of wedlock with Helene Demuth, the housekeeper of the Marx family. Engels made no big deal out of it. On the contrary: after the death of Marx, Helene Demuth moved into the house of Engels until her death. She was as much a part of his family as Marx’s daughters and the niece of the Burns sisters. His family was not based on blood relations, but rather reflected his unconventional lifestyle. Although he was quite wealthy, possessions and possessive thinking played no role for him. He lived in furnished apartments for rent throughout his life. One open question remains, however, why Frederick Demuth in particular was not considered in Engels’ will.

Although Marx’s tomb was originally intended as a communal grave for the whole “family” he felt he belonged to, Engels had it arranged that his ashes should be scattered in the sea near Eastbourne. The pilgrimages to Marx’s tomb, which had already taken place during Engels’ lifetime, repulsed him and made him seek his final resting place elsewhere.

What remains?

Engels lived an adventurous and eventful life, the majority of which he spent in exile. Together with Marx, both their lives were marked by many highs but also many lows. Despite many personal and political setbacks, they never gave up and lost sight of their common goal. Engels was an entrepreneur and revolutionary, something that is still held against him today by one side or the other. He thought little of personal vanities; he was proud only of what he and Marx had achieved. The Russian city on the Volga, named after him in 1931, would have surely alienated rather than flatter him. He always placed his own role in the overall context of the socialist movement, rejecting elevations and veneration like a saint. However, we must put into perspective his own assessment that he played only the second fiddle alongside Marx. It is not possible to evaluate the significance of Marxism between him and Marx, and most of all Marx would have refused to do so. He once wrote to his friend:

“You know that, first of all, I arrive at things slowly, and, secondly, I always follow in your footsteps.”