For months now, Canadians have been told over and over again that frequently washing our hands with soap and water for at least 20 seconds is one of the best ways to prevent the transmission of COVID-19. For thousands of people living in First Nations communities without clean drinking water, this is easier said than done. There are currently more than 100 water advisories in First Nations communities across Canada. For those on “do not use” advisories, their water is not safe for any purpose; they need to use bottled water with soap or hand sanitizer with at least 60% alcohol.

We’re not “all in this together”

COVID-19 has shown that it does discriminate, contrary to the “we’re all in this together” mantra that we hear from government and corporate CEOs. Indigenous communities are among the most vulnerable to the coronavirus. For those living on reserve, without clean drinking water and housed in crowded conditions, the risk of getting the virus is greater. More than a quarter of people living on reserves live in crowded homes, a rate seven times of that of non-Indigenous people. As many as 43 percent of homes on reserves need major repair. Even without a pandemic, these poor living conditions contribute to ill-health including an increased prevalence of infectious diseases such as tuberculosis, bronchitis and influenza.

For those living in remote communities, including First Nations and Métis in northern Canada and the Inuit in Nunavut and Nunavik, the prospect of the pandemic affecting their communities is terrifying. Small, isolated communities have limited access to medical staff and lack hospitals. A big worry at the outset of the coronavirus was that, even in big cities, the pandemic would cause our hospitals to become overwhelmed with people needing intensive care. Hospitals began clearing out patients, cancelling elective surgeries, making extra beds available for COVID-19 patients. Canada did not want to experience the tragedy we witnessed unfolding in Italy of hospitals and medical staff becoming completely overwhelmed. Another concern was the lack of ventilators with a mad scramble to obtain more ventilators.

Many Indigenous communities do not have any ventilators let alone intensive care units or doctors. Instead, many, particularly in northern isolated communities, have nursing stations that are ill-equipped and understaffed. Many also do not have adequate levels of personal protective equipment (PPE). If their members get ill, they need to be transported out of their community.

Indigenous communities work to protect members from COVID-19

Indigenous communities and Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut have worked extremely hard to prevent the transmission of any cases in their communities, given the difficulties of managing even small numbers of people with COVID-19. Despite having to fight governments and courts to enforce physical barriers, such as northern Manitoba First Nations did in blocking access to the Keeyask Generation Station construction site, about 725 kilometres northeast of Winnipeg, measures have been taken in many communities to put up physical blockades and checkpoints and close their borders to outsiders. Indigenous communities also have focused on public education and in some cases, imposed curfews. So far, Nunavut has not had any cases while the Yukon and Northwest Territories have had 11 and 5 respectively, all of whom have recovered. Nunavik, in northern Québec, had 14 people confirmed with COVID-19, in three separate communities. They have all recovered.

Over the past two months, the number of Indigenous communities affected by COVID-19 continues to rise. As of June 15, Indigenous Services Canada reported 247 people on reserves who have been confirmed positive with COVID-19; 208 have recovered, 22 hospitalized, and 6 people died. The regional breakdown is as follows:

- British Columbia: 43

- Alberta: 60

- Saskatchewan: 56

- Ontario: 53

- Quebec: 35

Less than half of the Indigenous population in Canada live on reserves. While it is unknown how many Indigenous people living outside reserves or in urban areas have become ill with the coronavirus, it appears that the biggest outbreak in an Indigenous community was in La Loche, a Dene village 600 kilometers northwest of Saskatoon. Socialist Alternative reported on May 12 that 120 people had COVID-19, an infection rate of 4% – more than 18 times the overall national infection rate at that time. Gary Vidal, MP for northern Saskatchewan, called the “very dangerous situation” around La Loche “the most concerning outbreak of COVID-19 in Indigenous communities in Canada.”

The APTN (Aboriginal People’s Television Network) has also tracked COVID’s impact on Indigenous communities. Their map highlights the specific First Nations communities that have had COVID-19 outbreaks. This map shows La Loche having had 143 cases, including 3 deaths; a cluster of communities around La Loche have had cases as well. Other significant outbreaks have occurred in the Namgis First Nation in BC (30 cases), Kahnawake Mohawk Territory in Quebec (21 cases), Clearwater River Dene Nation in Saskatchewan (16 cases), Six Nations of the Grand River (14 cases) and Wapole Island First Nation (14 cases) in Ontario, and the Bearspaw First Nation (14 cases) and Blood Tribe (14 cases) in Alberta.

Urban Indigenous communities at high risk

In urban areas, it is not clear how many Indigenous people have had COVID-19. The data from provincial health authorities does not provide this type of breakdown. However, it is clear that for many people, including those who are Indigenous, the health crisis of the pandemic itself is compounded by a host of other factors. The physical isolation can lead to mental health concerns as well as concerns about domestic violence. Violence against women is an issue we have written about previously. Indigenous women in Canada experience higher rates of domestic violence compared to non-Indigenous women and disproportionate rates of domestic homicide. Domestic homicide rates among Indigenous people were twice the rate among the non-Indigenous population. Indigenous people living in urban areas experience higher rates than non-Indigenous people of homelessness, poverty and imprisonment. All of these contribute to a heightened risk of COVID-19.

Alongside COVID-19, there is an alarming rate of opioid deaths. In BC, 170 people died in May from opioid poisoning, the highest number of opioid deaths ever seen in a month. This was a 44 percent increase over the previous month and a 93 percent spike over the number of deaths in May 2019. This increase is partly attributed to the physical isolation during the pandemic; people are taking opioids while in isolation and thus, are at a higher risk of dying. While it is unknown how many of those died were Indigenous people, a study in 2017 found that in BC and Alberta, First Nations people were five times more likely than non-First Nations people to “experience an opioid-related overdose event and three times more likely to die from an opioid-related overdose.”

The Social Determinants of Health apply to COVID-19, like other causes of ill-health. This concept is described by the World Health Organization as “the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life.” For Indigenous people growing up in Canada, conditions such as poverty, poor housing, inadequate food security, lack of access to basic amenities such as clean drinking water and under-funded education, all contribute to ill-health. Poverty is one of the biggest indicators of ill-health in Canada. The Evidence Network maintains that “substantial and robust evidence confirms a direct link between socioeconomic status and health status ― meaning people in the lowest socioeconomic group carry the greatest burden of illness. Research demonstrates that there is a “social gradient” in health that runs from top to bottom of the socioeconomic spectrum of life.”

Systemic racism threat to Indigenous communities

The wider forces and systems that shape these conditions include the availability of support networks, government and wider-system support and the reality of systemic racism that Indigenous people face in their interactions with many of the institutions in society: schools, health services, police, the legal system and media.

All of these factors make Indigenous people more vulnerable to COVID-19. Another factor that affects the prospects for recovery from COVID-19 is the existence of underlying health conditions. A relatively high number of Indigenous people are affected by diabetes, which also makes them more vulnerable to the impact of COVID-19.

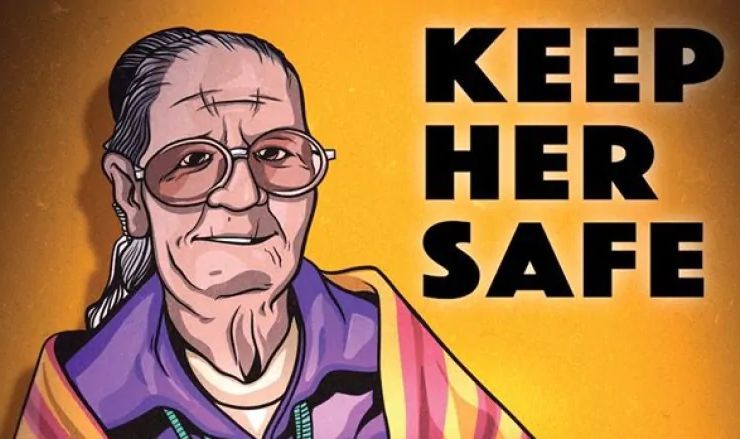

Several Indigenous elders have died from COVID-19. The APTN commemorated some of the lives that COVID-19 cut short. Several of these were respected elders living in long-term care. Others lived in their communities, such as Cindy Mountain from Alert Bay, the “first First Nations elder to succumb to the deadly virus in B.C.” “Cindy, 59, got sick despite following public health directives. She stayed home. She washed her hands. She thought it was a cold. But it worsened. Then it became critical. On April 24, she died.”

Youth fight for better future

On the other hand, the relative youth of Indigenous communities is one factor that offsets these other risk factors. Evidence shows that younger people are less likely to get seriously ill from COVID-19. The built-in resilience of youth and children are signs of hope for the prospects of Indigenous resilience against COVID-19. Many are fighting back, not only against state violence and police brutality, but are fighting for a better future for their communities.

It is resistance, determination and struggle that will prevail in the fight against COVID-19. The same is true against the pervasive systemic racism faced everyday by Indigenous people and against the colonial, capitalist system which is a menace for people everywhere. It will take determination to overcome the obstacles that capitalism puts in our way. A better way forward for humanity is urgently needed. It is only in a socialist society, where the needs of people and the planet come before profits that all humanity will thrive. Who better to lead us to this future than today’s youth?