Not even COVID stopped the determined actions of Indigenous land defenders. They carried out some of the biggest actions that Canada has ever seen in response to the further invasions of sovereign Indigenous territories by the Canadian state. Peaceful blockades and rallies took place on rail lines, parliament grounds, various cities’ intersections and at government ministers’ offices.

There was an international outcry at the RCMP’s violent invasion of Wet’suwet’en lands and the threats to peaceful elders by heavily armed paramilitary forces. The momentum of action was building as COVID swept across the nation. Yet still, Wet’suwet’en land defence continues.

Despite COVID, struggle has continued. Members of the Six Nations have been at their reclamation camp, 1492 Land Back Lane, since July opposing a housing development on unceded lands in Caledonia, Ontario. A treaty in 1784 granted land, including the 1492 Land Back Lane area, to Six Nations along the Grand River. Yet courts have issued an injunction against the land defenders and there have been multiple arrests.

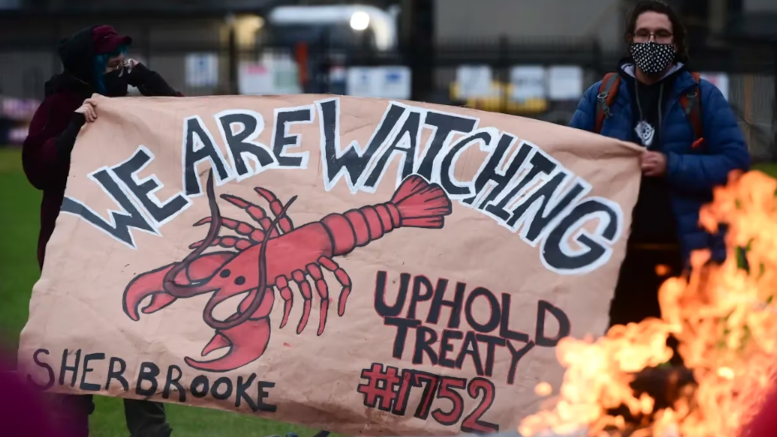

Mi’kmaq treaties, of 1760-61, guarantee their right to sustain a “moderate livelihood.” The 1999 Supreme Court of Canada Marshall decision upheld this right, yet in 21 years Canada’s Department of Fisheries and Oceans has not acted to enforce this right. On September 15, Sipekne’katik First Nation announced they would be launching the Sipekne’katik Rights Implementation Fishery. Non-Indigenous commercial fishers violently attacked and intimidated Mi’kmaq fishers, destroying equipment and property. The RCMP stood back and watched.

Pre-COVID, fights against damaging extractive resource projects showed governments’ and industry’s blatant disregard for Aboriginal Title. Despite the government pledging to act on the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls report, they ignore the harm caused to Indigenous women, girls and Two-Spirit people when in proximity to man-camps. The pandemic added another dire layer: the large numbers of workers criss-crossing remote Indigenous territory brought greater risk of COVID-19 to remote communities. Elders are knowledge and language keepers in communities; they are also the most vulnerable to this disease. Unsurprisingly, outbreaks have occurred at work sites, including Site C dam, two along the LNG pipeline running through Wet’suwet’en, and at the Kitimat LNG site. Only on December 29 was a health order issued to limit the number of workers at sites.

People have not experienced this pandemic the same; poverty, inequality and mental health have all worsened with the woeful responses from all levels of government. Indigenous communities are particularly vulnerable. It is impossible to wash hands frequently with unsafe water. There are 58 long-term drinking water advisories in effect in 40 reserve communities. It is impossible to physically distance in over-crowded housing. Health facilities in remote communities may not exist or are not capable of handling an influx of patients. Even with a vaccine rollout, COVID’s impact will last for years.

Capitalism did not cause COVID, but the pandemic has exacerbated every hellish nightmare capitalism breeds. Unemployment, debt, loss of income, grief, housing insecurity were bad before the pandemic and now they are worse.

Underlying all the Indigenous struggles is the issue of land. Capitalism’s view of land is explained by Locke, a 17th Century English philosopher, “[e]ven if land is occupied by indigenous peoples, and even if they make use of the land themselves, their land is still open to legitimate colonial expropriation,” as capitalist use will increase the exchange value realized from it. In contrast Indigenous people, and all who care about the environment, say people should not exploit the land but rather like a good family “they must hand it down to succeeding generations in an improved condition,” to quote Marx.

No gesture by politicians saying they support Indigenous rights can overcome the contradictions over land. The 2020s will further push youth and the working class to join in solidarity with Indigenous peoples’ struggle. Land should be cared for by all, for the well-being of all for the next seven generations to come.