It would be a grave mistake for the NDP and union leaders to assume that everything is back to normal now that the convoy has ended. It isn’t. The convoy provoked a decisive change in Canadian politics, with the alt-right pumped after the successful encampment and US border blockades. But more importantly, these actions have sparked an open shift to the right of a section of society. The Conservatives kicked out the “moderate” leader, O’Toole, replacing him with a right-wing interim leader, Candice Bergen. Bernier’s right populist People’s Party of Canada saw a small boost in the polls.

The convoy struck a chord with millions of desperate people, exposing the deep anger and alienation that already existed. Fewer Canadians identify with the political centre; they are no longer satisfied that Canadian society is moving in a good direction and are beginning to look for radical change.

The Liberals are seen as the party of the status quo, at a time when young and working-class people are increasingly frustrated. The populist right has simplistic answers that can have a powerful appeal. Their voice seems loud because of a lack of a compelling alternative.

The way to fight back against the right wing is to build a strong working-class movement with demands that address the worsening conditions facing ordinary people. A dynamic movement, led by unions and supported by the NDP — for better wages and conditions, affordable housing, childcare, dental care and pharmacare and for real action on the environment and a Just Transition — could channel the justified anger and frustration of ordinary Canadians.

NDP and Liberals form pact

The NDP, however, has chosen a different path. This was foreshadowed by the NDP giving support, albeit “reluctantly,” to the Liberals’ unnecessary and freedoms-infringing Emergencies Act to deal with the dismantling of the “Freedom” convoy. Contrast that with former NDP leader, Tommy Douglas, and his refusal to go along with Pierre Trudeau’s emergency legislation at the time of the Québec October crisis, in 1970. The NDP has moved closer to the Liberals with a Supply and Confidence Agreement that promises a number of reforms, including dental care, for Canadians — a small step forward. In return for this promise and vague “commitments” to some possible future improvements, the NDP has agreed to support the Liberals for the next three years. This is a major stride backward.

The talks that produced this agreement began in the autumn between Trudeau and Singh and ramped up once the crisis of the convoy had ended. Singh and Trudeau both expressed concern about stability in parliament and collaborated to deliberately strengthen the political centre. The Supply and Confidence Agreement means that the NDP is not likely to bring down the Liberal minority government. Trudeau said the agreement is “a responsible answer to the uncertainty we’re in, to the challenges facing democracies with hyper-partisanship and toxic polarization,” adding that ” during this uncertain time, the government can function with predictability and stability.” Jagmeet Singh called it a marriage.

This agreement boosts the confidence of the Liberals to govern like they have a majority, without the maneuvering required to stay in power. And the NDP benefits by avoiding the risk of an election at a time when the party can ill afford it. While they could continue to support the Liberals on an ad-hoc basis, this agreement allows them to save face in supporting certain bills and measures, like increasing military spending, in exchange for the implementation of key aspects of their campaign, such as dental care, pharmacare and others. In the parliamentary sense, it suits both parties. The Liberals get stability (they can’t be removed in a non-confidence vote). The NDP will try to take credit for the progressive aspects of the program that get implemented. While that will play well to NDP partisans, in the eyes of the general public, the Liberals will be able to take much of the credit.

While on the surface, this agreement may appear to be a win for working-class Canadians and the NDP, in reality, it leaves a vacuum on the left and in the long-term may propel a right-wing shift in Canadian politics. As Michael Harris, put it, “How could the NDP run to replace the Liberals, after spending three years propping them up?”

The Conservative interim leader called the agreement “backdoor socialism,” whatever that means. Despite several conservative commentators’ view that this agreement pushes Canadian politics to the “far-left,” this agreement does not signal a shift to the left but a strengthening of the centre.

What’s involved

The new dental care program is the headline of the agreement, which is nearly identical to the NDP’s policy plank for the last two elections. Children under 12 could get dental coverage later this year if the plan goes ahead, expanding to under 18-year-olds, seniors, and persons living with disabilities in 2023, and then full implementation by 2025, with no co-pays for anyone earning less than $70,000 annually. The problem with means-tested programs is, while they save some money by excluding the well off, such programs are vulnerable to cuts, and they can be a bureaucratic nightmare to access, which most penalizes the poorest. A universal program has the advantage of including the poor and broader middle class. Singh has a history of supporting means tests. When he ran for the party’s leadership, he called for old age security, which currently goes to anyone over 65, to become completely means-tested. Socialists reject means-testing whether it be Liberals, NDP or both that are carrying it out.

In addition to the dental care program, the agreement calls for a number of other initiatives, taken from either the Liberal platform, the NDP platform or both. These include “moving towards” a universal national pharmacare program, tabling a “Safe Long-Term Care Act,” housing affordability measures, supports for workers, Indigenous reconciliation initiatives and tax fairness measures.

What about climate change and military expenditure?

Climate change is the most important issue facing Canadians and, indeed, humanity. The agreement commits to “tackling the climate crisis and creating good paying jobs.” But with nothing on stopping the Trans Mountain pipeline, these are empty words. The NDP should have pushed hard on this. Socialist Alternative has discussed the out-of-control costs of this project, now estimated at $21.4 billion. From the beginning, this project was inconsistent with meeting global climate emission targets. The International Energy Agency, a formerly pro-oil lobbying group, says that all new investments in fossil field production must stop now if global temperature rises are to be kept below the 1.5C limit and prevent cascading climate catastrophe. If completed, the Trans Mountain expansion would triple the amount of oil flowing from Alberta to the BC coast. According to the Climate Action Tracker, Canada missed its 2020 emissions target, even after the pandemic caused a drop in emissions. And the Liberal government’s climate targets from the 2021 budget are not good enough to meet its Paris Agreement commitments, which themselves weren’t sufficient to avoid the 1.5C limit.

Then there’s the military, an area that is not mentioned in the Liberal-NDP agreement. Flowing from the war in Ukraine, the Liberals are under strong pressure to increase military expenditure including arms exports and to meet the target for NATO counties of spending 2 per cent of their GDP on the military. This would require an additional $16 billion in military spending over the roughly $30 billion already spent each year. This is in addition to the almost-completed purchase of replacement fighter jets whose full lifecycle cost comes in at a cool estimated $77 billion!! The NDP’s position is to move forward with replacing the existing jets, with the qualification that the new aircraft must be able to operate in the Arctic and the program should create jobs in Canada. Workers need good jobs, but instead of increasing military spending, which is making climate change worse, the government should be creating green jobs as part of a just transition. It’s a scandal that the NDP is going to agree to this massive military spending while accepting the crumbs of a mediocre dental plan and a climate action plan with very little action.

Precedents: Gained more but gave less

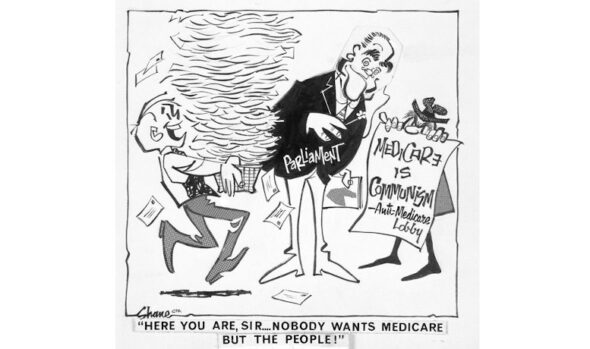

To justify this agreement, NDP activists have referred to past precedents. One such precedent was the success of the Saskatchewan Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), predecessor to the NDP, in winning publicly-funded health care in the face of virulent opposition from the province’s doctors. It was the mobilization of ordinary people through extra-parliamentary struggle that won the day, forcing doctors to accept the public health care insurance system.

Tommy Douglas, the premier of Saskatchewan who campaigned on this during the 1961 provincial election, moved to federal politics and supported the Liberal minority government in winning this important reform on a national basis. The NDP used its balance of power in parliament to win a national health care program, despite opposition from the Tories. The broader political and economic context made this possible. In addition to the left-wing shift in the general public, the post-war boom of the 1950s and 1960s saw strong growth in the economies of the western capitalist world and this meant that governments were more willing to finance such an expensive program.

After the 1972 election, the NDP once again held the balance of power, which they used to support Pierre Trudeau’s narrowly-won minority government. In response to the global crisis in oil prices, many on the left were calling for the nationalization of the whole energy industry. Instead, the NDP put forward a compromise motion calling for just one national oil company, which the Liberal government eagerly accepted. Petro Canada was eventually founded in 1975, and it was later privatized by Mulroney in 1990. In exchange for offering a soft-ball compromise position to the Liberal government, the NDP was decimated in the 1974 election that they themselves triggered, losing half their seats.

In 2005, Jack Layton made a deal with PM Paul Martin. It led to what Layton called an “NDP budget.” The NDP website waxes lyrical: “Months after taking his place in Parliament, Layton displayed his remarkable ability to get things done for families. By rewriting the 2005 budget, Layton successfully diverted $4.6-billion from corporate tax giveaways to important priorities like affordable housing, education and public transit.” What they don’t say is that it included the largest increase in military spending in 20 years. In the 2006 election the NDP came in third, gaining only 29 seats.

The NDP’s biggest electoral victory occurred in 2011. They benefited from the complete collapse of the Liberal Party, winning their best ever result of 103 seats — the famous “orange crush.” This campaign was not built on a bold left-wing program including concrete promises for the working class, but instead relied strongly on the charisma of Jack Layton. After Layton’s unfortunate passing, the party doubled down on running to the centre by choosing former Québec Liberal MNA Thomas Mulcair to be leader, and the orange crush has never been repeated.

When the NDP made deals with the Liberal Party in the 1960s, 1970s, and 2000s, they were always about a specific issue in a specific situation. The recently announced deal differs significantly because it extends for three years, and it is vague on concrete proposals. It unnecessarily gives up the NDP’s ability to adapt to the changing economic and political situation and to re-evaluate what is possible to win in each circumstance, and it does not get much in return for giving up this opportunity.

International Lessons

The NDP is playing a dangerous game by trying to work too closely with the Liberal Party. Looking to examples around the world, in most cases when a smaller leftish party supports a larger more centrist party it is the left that fares the worst.

In Ireland’s 2011 election the Labour Party came second with 19.4 percent of the vote and won 37 seats. It formed a coalition with Fine Gael. In the next election in 2016, it was crushed dropping to fourth with only 6.6 percent of the vote and just 7 seats. It has not recovered since and risks disappearing, to be replaced on the “left” by Sinn Féin.

In Spain, after the deep recession of 2008-09 Podemos (We Can in English) emerged as a dynamic left force, opposed to austerity. By 2014 it had the second largest membership of any party in Spain and in December 2014 was polling at 30 percent support. However, it kept drifting towards supporting the formerly left PSOE. In the elections in 2015 and 2016 it won 21 percent of the votes. It worked with the PSOE and lost votes in the two elections of 2019, dropping first to 14 percent and then 13 percent. It then formed a coalition with PSOE and its support has slid lower since.

In Italy, the Partitio della Rifondazione Comunista (PRC, Communist Refoundation Party in English) had huge potential when it was founded in 1991 as a new socialist, anti-Stalinist, and mass workers’ party. It emerged as a left-wing split from the Communist Party of Italy (PCI), and within months it had 150,000 members. Over the next decade, the PRC used revolutionary socialist rhetoric without understanding how to use class struggle methods to win mass working-class support, but still the potential remained for revolutionary leadership to lead to a breakthrough. This potential was squandered by the party’s decision to join a coalition government with the centre-left capitalist parties in 2006-2008. The PRC leadership claimed they could “push the coalition to the left,” but in reality, they wielded no influence in the government and instead were implicated in the brutal austerity measures that were introduced. The result was that the PRC was completely wiped out in the 2008 election, losing all 66 of its MP and senators, and the party effectively no longer exists to this day.

The problem with the NDP

If this agreement did lead to socialism through the backdoor, then it would be welcome. However, it only delivers sub-par dental and pharmacare programs, and other measures that were already in the Liberal platform. In relation to housing, it contains “only more of the half-measures and vague promises found in both the Liberal and NDP platforms.” While there are progressive elements to the agenda, it is not particularly bold. While supporting these modest gains, workers need to ask what is being given up in return?

First, this is 2022, not 1966 when the national Medical Care Act was passed. The economy is not booming. The budget deficit is currently running at $73.7 billion. Even disregarding increased military expenditure, there will be tremendous pressure on both Liberals and NDP to accept cuts to government spending.

Some commentators, including Thomas Walkom of the Toronto Star dismiss the accord as “meaningless,” given that it does not commit government to fully implement programs and falls short on specifics and lacks enforceability. However, unlike Marxists who look at broader and long-term trends, many on the left fail to consider the long-term implications of a leftish party forming an alliance with a centrist party. Others do see the pitfalls including that “Co-operation could easily turn into co-optation for the NDP, as it so often has in federal politics.”

The problem with the NDP is that it sees everything through the lens of elections and parliamentary arithmetic. Further, its vision is short-sighted. It does not campaign day-to-day in communities and workplaces. There are no big rallies like in the Bernie Sanders’ election campaign. The malaise is at the top, accompanied by the lack of a vibrant organization at the bottom, which has been the case for some time. Its vision is progressive but not bold. It backs away from challenging the basic power relations in society: the working class versus those who own the means of production. It continually underestimates the ruthlessness of the elites. Its methods are not class struggle. Tommy Douglas cautioned: “We must never underestimate our opponents; nor should we forget that the closer we come to reaching our objectives, the more vicious and forthright will their opposition become.”

In contrast to the NDP of the past who fought tooth and nail for a public health care system, facing down opponents by mobilizing in the streets, today’s NDP prefers to sidle up to the ruling party to try and etch out a better deal for “ordinary Canadians.” This strategy is a recipe for extinction.

Following the “Freedom Convoy,” Canada has become increasingly polarized. Normally this would see the poles of right and left become stronger while the centre gets squeezed. We’ve certainly seen a strengthening of the right. This agreement is one further step along the continuum towards vacating the left in an attempt to strengthen the centre. But eventually, the centre will not hold. This may mean that the Liberals, supported by the NDP, will open the door for a right-populist Prime Minister, one who is emboldened to use the Emergencies Act against Land Defenders, workers on strike and environmentalists.

Socialist Alternative stands by what we wrote after Singh’s leadership win in 2017: “The NDP will need a radical transformation if it is to meet the needs of most Canadians. What is needed is a democratic party controlled by the membership, that campaigns year-round in communities and workplaces, and supports struggles. The party needs a program to tackle the power of big business and the wealthy minority, redistribute wealth to raise wages and provide good public and social services, end all forms of discrimination and create an economy with full employment and a healthy environment. Singh’s victory does not advance this change, it will take working class struggles.”